Merlin: A Retrospective

Good afterevenmorn, Readers!

I have been rewatching a few things as I move through this last part of 2025. I’m not sure why I’m feeling nostalgic, but I am. Part of that rewatch is BBC’s Merlin. I watched this as it aired, all the way back in 2008. I adored it then, and I adore it now. No doubt, part of the adoration now is very much tied to how much I loved it as I was discovering the series for the first time. A not insignificant part, however, is because this show is just good.

There’s something about the way this show is written, largely shared by much of British writing, that carefully balances the ridiculous with the extremely serious, whimsy and sobriety, light and humorous and very, very dark. This isn’t specific just to Merlin, but reaches into many shows written by British writers, I’ve noticed. Doctor Who is another one that comes to mind that does this wonderfully.

I believe it’s largely because these writers live in a landscape absolutely saturated in myth and legend that date back millennia; the stories attached to them told and retold for generations. Many of these stories are fairy stories, “histories” that include the use of magic as if it was fact, truths buried beneath tales of druids that scold monsters residing in lakes, or having lightning battles with one another.

Stonehenge was built by druids, or the devil, or giants, as was the Giant’s Causeway, a remarkable basalt column formation in Northern Ireland, which used to be a bridge that stretched across the Irish Sea so that the giant Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool) might cross the sea to either fight his rival or meet with his Scottish lover, depending on the teller of the tale. It’s connecting point was Fingal’s Cave, which shares the same geologic features as the causeway, and is named for the same Irish Giant.

The land is dotted with thousands of unexcavated barrows, cairns, passage tombs and other burial mounds, all with stories attached, most having to do with the fairy people (Sídhe, in Ireland), or mythological heroes that have been rumoured to have stood upon, or be buried within.

These stories are both full of peril and wonder; the wonder of magic, and the peril of a world where terrible creatures lurk in the shadows. The impossible and plausible all swirl together to create a story-telling sensibility that is as I’ve described both full of whimsy and wonder, and are also incredibly dark and disturbing.

It’s in this cultural milieu that has made it possible for shows like Merlin, which are both incredibly silly, and extremely heartfelt and often very tense.

But enough of why I, personally, think it’s such a thread in British writing, and more about the show itself.

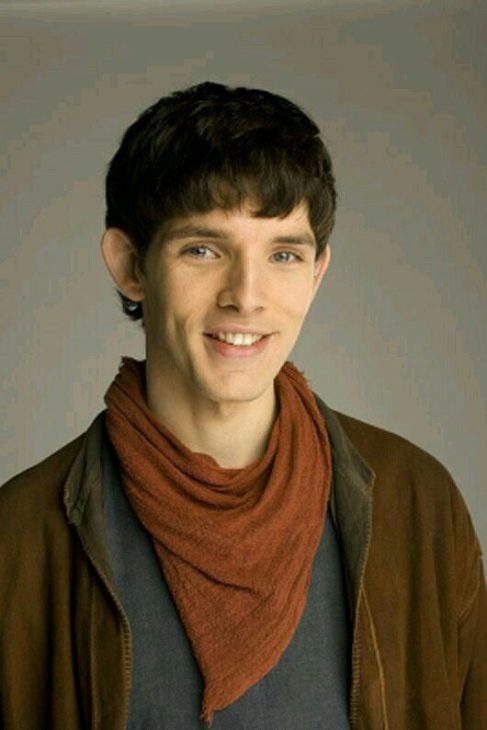

For those who have not watched the show, it’s a delightful retelling of the famous Arthurian legend from before Arthur is made king of Camelot. Largely based on the medieval myths (if the inclusion of Lancelot didn’t give it away), rather than the earlier Celtic myths, and not at all on the possibility of a historical Arthur, the show centres on a young Merlin, who comes to Camelot and finds himself improbably employed as the personal servant of a young Prince Arthur.

Merlin is a sorcerer… or a wizard… A magic user of some kind… in a kingdom that has outlawed all magic, branding it, and all who use it, as a great evil and existential threat. This is by the decree of Uther Pendragon, king of Camelot and often tyrannical parent figure to both Arthur and Uther’s ward, the Lady Morgana (who is not related to Arthur in this retelling, but is the daughter of one of Uther’s closest, long dead friends). Uther’s hatred of magic informs everything he does, and often leads him to unspeakable acts.

It also means that Merlin must hide his abilities. Yet he is also charged with protecting Arthur, both by the king, and by the dragon chained in the enormous caverns beneath the castle. It is Arthur’s destiny to rule Camelot as an honourable, benevolent king, uniting the magical and non-magical worlds; counterbalancing the tyranny of his father. And it is Merlin’s destiny, we learn, to ensure Arthur becomes that king.

What develops is a beautiful friendship. There are many adventures. Some of them are silly. Some of them are dire. All of them are entertaining. There is an overarching narrative, of course, but each episode is usually self-contained. Sort of an old-school monster of the week kind of show.

It has one of my favourite tropes, namely enemies to brothers (between Merlin and Arthur, who don’t exactly get along on their first meeting). There’s also forbidden love and love conquers all (between Guinevere and Arthur… because Arthur is a prince, and Guinevere a servant in this retelling). And there is also the creation of a villain, which has to be one of my favourite things, narratively speaking. Merlin does it particularly well, as it explores how tyranny creates the very thing it’s trying to avoid or control. A person can be abused only for so long before they bite back. When it happens, it’s understandable.

In fact, Merlin excels in creating brilliant, multi-dimensional characters whose motivations make sense. Evil isn’t evil for the sake of it. There’s almost always a reason for it. For example, Uther’s quest to exterminate magic, whose tactics include the attempted extermination of entire peoples, has directly resulted in the resistance of magic-users, who go after Uther, his loved ones and his kingdom. But theirs is an act of desperation. They are fighting for their very survival. Would I also not try to remove the thing that threatens to murder my entire people? Uther is not a good man. How he raised a son like Arthur is anyone’s guess.

Sure, there are some inconsistencies that are created largely for the plot – Arthur’s character sometimes swings wildly between having grown as a person, becoming kind, compassionate, and considerate, and then regressing back to the spoilt little bully he was introduced to us as. But overall, they did an incredible job with all of the characters.

The Lady Morgana, wonderfully portrayed by Katie McGrath, remains my favourite from the series.

The point is, even after all this time, Merlin holds up. It still works. It’s not a perfect show by any means, but it tickles all the right parts in my mind; it’s funny and fun, but also heartfelt and dark. It’s full of whimsy and nonsense, and also tackles issues of intolerance and revenge. It’s bright, and also dark.

This is not an easy line to tow, and the writers of the show should be very proud of what they created. Because it still holds up (early 2000s CGI notwithstanding), even now, not far from twenty years later. I highly recommend a rewatch, and if you haven’t seen it before, I definitely recommend a watch. It’s a warm apple cider on a chilly day of a show.

When S.M. Carrière isn’t brutally killing your favorite characters, she spends her time teaching martial arts, live streaming video games, and sometimes painting. In other words, she spends her time teaching others to kill, streaming her digital kills, and sometimes relaxing. Her most recent titles include Daughters of Britain, Skylark and Human. Her next novel The Lioness of Shara Mountain releases early 2026.

“The impossible and plausible all swirl together to create a story-telling sensibility that is as I’ve described both full of whimsy and wonder, and are also incredibly dark and disturbing.”

Wow, that is primarily what I wanted in my Pendragon RPG campaign. And Lady Morgana is a main character? Yes, I am adding Merlin to my bingeing list for next summer (and my regional library system has DVDs for all 5 series). Thank you, Ms. Carriere, for reminding us of this overlooked gem!

You’re welcome! And enjoy! I do.

Also, just a quick note to shout out libraries. They’re awesome.

I have to say, one of my very favorite Al Stewart songs, “Merlin’s Time,” beautifully captures that atmosphere.

I am not familiar with it. I’ll look it up.

Oh, that is on “24 Carrots”! Time to pull it off the CD rack and re-listen.

I hadn’t remembered that, or looked it up. 24 Carrots also has my other very favorite Al Stewart Song, “Murmansk Run/Ellis Island,” an elegant bit of parataxis.

I am a sucker for his “Flying Sorcery” (found on Year of the Cat), since aviation, particularly early, is such an interest for me. But, I really would not turn down any of his songs.