After Fifty Years: Childhood’s End

Like a lot of people, I fell under science fiction’s spell during those intermediate years when childhood blurs into adolescence, and fortunately for me, there was a thrift store around the corner from my middle school, with shelf after dusty shelf of used paperbacks that you could buy for twenty five or thirty cents apiece. Every day when school was over, I would take my lunch money and go there and, attracted by the outlandish, gaudy covers, spend my daily seventy-five cents on sf paperbacks (sorry, Mom).

My first discoveries and greatest loves were Robert A. Heinlein’s juveniles and his Stranger in a Strange Land (way too young to be reading that one), Isaac Asimov’s robot stories (I had a thing for Susan Calvin), and Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles and his wonderful, phantasmagoric short story collections S Is for Space and R Is for Rocket. Along with volumes from the anthology series like Star and Spectrum that were once so common and sadly no longer are, these books and authors formed the haphazard curriculum of my science fiction education.

One author was largely missing from my course, though — Arthur C. Clarke. Oh, I had read the three classic stories that turned up in so many of those anthologies — “The Star”, “The Nine Billion Names of God”, and “The Sentinel”, but of Clarke’s many novels, the only one I read back then was his 1953 evolutionary drama, Childhood’s End. Like Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land but for different reasons, I was too young (fourteen) to fully appreciate the book; I liked it well enough, but it didn’t spur me on to read any of Clarke’s other novels.

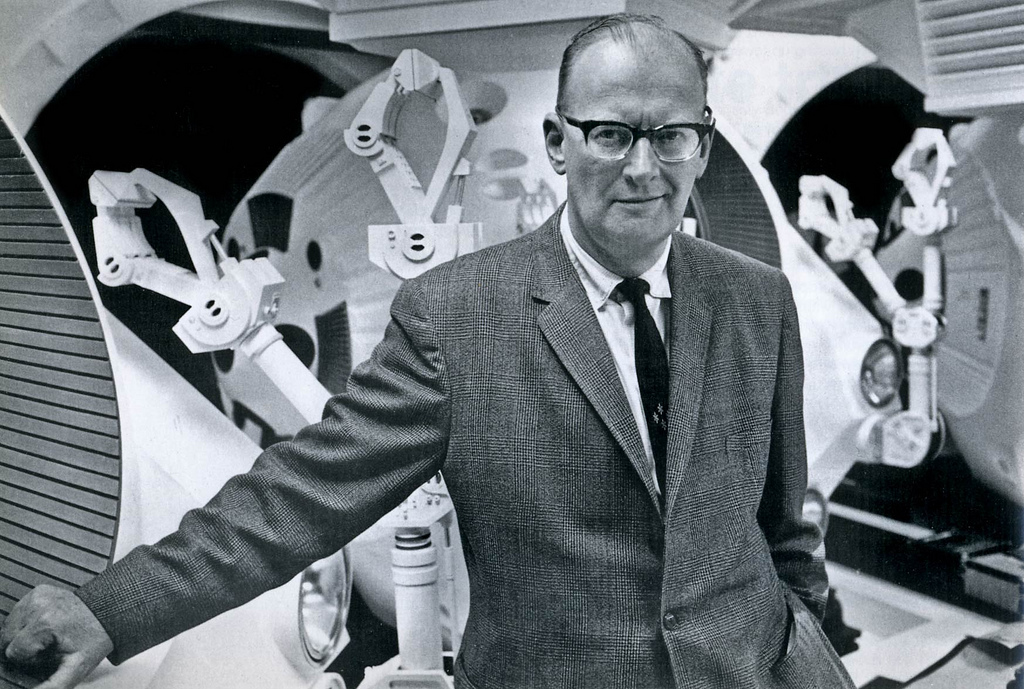

Over the past several years, though, I have been rectifying my neglect of one of the undisputed giants of twentieth century science fiction, and I’ve read The City and the Stars, Earthlight, A Fall of Moondust, The Deep Range, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Rendezvous with Rama, and The Fountains of Paradise, and I’ve enjoyed them all immensely.

Therefore, I decided that it was time for me to close the circle and revisit the book that I first read a half century ago and that didn’t make the proper impression on the callow teenager that I was then. Beyond the general premise and a lingering impression of a chilly, lonely melancholy, I found that I remembered very little about the book.

Structurally, the story is simplicity itself, a one-two punch, setup followed by a knockout payoff. One day, completely without warning, just as the human race is about to step out into space in a first effort to leave the prison of Earth and its solar system behind, the alien Overlords arrive. Practically, their knowledge and power seem almost unlimited and they quickly place the governments and people of the globe under their authority.

We don’t know where they come from or why they have come at all (or even what they look like — they never emerge from the enormous ships that hover over Earth’s major cities, and their leader, Karellen, gives his directives to the UN secretary general without ever showing himself.)

The Overlords quickly prove to be the ideal liberal technocrats, and under their benign rule, all of the problems that have bedeviled the human race throughout recorded history rapidly vanish. Poverty, disease, discrimination and war are soon things of the past. Within a generation, a divided planet that was on the verge of annihilating itself becomes a unified utopia. And yet…

The great, unanswered questions nag at many of Earth’s citizens, at least at first, and they nag at the reader, too — why are the Overlords doing this? Why have they really come? Do they have a hidden motive for their intervention, and if so, what is it? Most people’s distrust is connected to the most basic question of all — why won’t they show themselves? And why, of all things, have they prohibited human space travel? Just what are they hiding?

Fifty years after their arrival, the Overlords come out of their ships and prove to bear a startling resemblance to the horned, bat-winged devils of myth and legend. They waited half a century to reveal themselves because the human race, still wrapped in conflict and shaped by superstition, was not yet ready to see them, but having “grown up” a bit under the aliens’ tutelage, the threat that their diabolic appearance would cause significant trauma had become minimal. (The widespread assumption is that the Overlords had made an unsuccessful visit to Earth in prehistoric times, an abortive encounter that implanted their “evil” image deep in the human consciousness. Like so many human guesses, this proves to be wide of the mark.)

Despite their apparent benevolence (a good will which is, in fact, actual), the Overlords (our term, not theirs) are indeed hiding something, for the very good reason that it is too enormous to be shown. The secret will reveal itself when the time is ripe.

That time is about a century after the Overlords’ arrival, when something strange starts to happen to the world’s children, beginning with one little boy, Jeff Gregson, who starts to have very odd, very disquieting dreams, dreams that seem to take him beyond human experience, far away from Earth and the things of Earth, even beyond the limits of the galaxy itself. It is not long before Jeff is not just dreaming strange dreams but is also manifesting extraordinary telekinetic and precognitive powers.

The Overlords are watching the boy, and they know that Jeff’s seemingly unique experiences are like the splitting of the single atom that starts the chain reaction, and so it is. Soon all the children of Earth, from about ten years old down to newborn infants, are having the same experiences and showing the same powers. It is then that Karellen speaks, not to a single human intermediary, but to the entire human race, and finally tells them the Overlords’ purpose in coming to their planet.

They did not come of their own volition, and they did not come to rule; they were sent as servants by… someone? Something? However you want to characterize what sent the Overlords, it is as far above them as we are above what H.G. Wells called the “infusoria under the microscope”, and it sent them to oversee the transition of the human race, from embodied, mortal, separate beings into part of a limitless, universal, non-material and utterly un-human consciousness, an “Overmind.”

This is what is happening to the children of Earth, with the Overlords merely acting, as one of them says, as “midwives” to this next step in the evolution of homo sapiens, an evolution that has a doubly tragic aspect.

Only the children are making the leap; everyone else is being left behind, which is of course doubly agonizing for the parents of those children, who see their beloved sons and daughters change irrevocably into something unfathomably alien; little comfort to tell bereaved mothers and fathers that what is a tragedy for the individual is a triumph for the race. (And whether from some biological change or simply because the race knows that it is “finished”, there will be no more children, ever.) All that the human race has been, everything that it has built and striven for and wept for and bled for and gloried in, all that is now as the sloughed-off, worthless, discarded husk that a molting insect leaves behind. The entire drama of human history and civilization is less than nothing to what the children are becoming.

The Overlords, too, have their tragedy, and it is that they are an evolutionary dead-end; they must always remain ineluctably mortal, chained to materiality, and can never evolve to become part of the Overmind.

The end of the book is profoundly moving. Jan Rodericks, an astrophysicist who had stowed away on an Overlord ship that was returning to their planet (before the secret was revealed), returns home after eighty years (because of relativity, only about six months have passed for him) to find himself the last man on Earth. Everyone else has either evolved (the children who are no longer children, for the moment still retaining physical bodies, have congregated together to await the time when they will discard those forms to join the Overmind) or died off, some naturally and others by suicide. The Overlords must remain behind until just before the final moment. They are willing to take Jan back to their world to live out the rest of his life, but he decides to stay; he knows that the Overlords were right when they said that “the stars are not for man.”

When the Overlords depart, Jan faithfully reports to them what he sees as the children make the final leap; when they transform into pure, immortal mind and soar into space to join that which is calling to them, the Earth cannot bear the strain. “In a soundless concussion of light, the Earth’s core gave up its hoarded energies” until, finally, “There was nothing left of Earth: They had leeched away the last atoms of its substance.”

As his ship heads for home, Karellen listens to the last words of the last man, and his long exile over at last, the alien reflects on what he has just witnessed, in what is still probably one of the most justly famous passages in all of science fiction:

For all their achievements, thought Karellen, for all their mastery of the physical universe, his people were no better than a tribe that had passed its whole existence upon a flat and dusty plain. Far off were the mountains, where power and beauty dwelt, where the thunder sported above the glaciers and the air was clear and keen. There the sun still walked, transfiguring the peaks with glory, when all the land below was wrapped in darkness. And they could only watch and wonder; they could never scale those heights.

Yet, Karellen knew, they would hold fast until the end: they would await without despair whatever destiny was theirs. They would serve the Overmind because they had no choice, but even in that service they would not lose their souls.

Karellen watches the Solar System — now with one planet less — dwindle in the viewing screen, as he silently salutes “the men he had known”, until, his thankless task finally completed, he turns away from what had once been Earth.

Childhood’s End, especially its solemn ending, is undeniably, darkly powerful in much the same way a great minor-key symphony is, and in this it’s well-served by Clarke’s plain style, which is able to convey the deep emotion of the situation through its very quietness and restraint; here more would certainly have been less. His prose is always clean and clear and the absence of any stylistic friction makes him a pleasure to read.

But aside from noting how well the book is structured and written, what now strikes me most about the novel, fifty years after my initial encounter with it, is the same thing that must surely strike any reasonably attentive reader who’s not in the seventh grade (and probably a lot of them would pick up on it) — how, despite its categorization as science fiction (and also despite Clarke’s oft-expressed hostility to religion) Childhood’s End is fundamentally a religious book, a statement of faith, in fact.

There are all kinds of faith in all kinds of things, of course. First, Childhood’s End is full of the secular faith that I have found in everything that I’ve read by Clarke — his great, baffling (to me), almost touching belief in the efficacy, rationality, and benevolence of large bureaucracies, which is, in my experience, a proposition not amenable to proof; quite the opposite, in fact.

But though Clarke’s child-like trust in bureaucracy is faith of a sort (his image could be the logo for the UN the way Jerry West’s is for the NBA), the genuinely religious core of his novel is found somewhere else, specifically in its treatment of evolution and its role in human destiny. Evolution is, in ordinary circumstances, a scientific doctrine. Not here, though. Put it like this — if in Clausewitz, war is politics by other means, in Childhood’s End, science is religion by other means.

Under the Overlords, people enjoy peace and plenty, and they have every benefit that rational social organization and advanced technology can offer, and it isn’t enough. Under a purely materialistic view of life, it should be enough… but the people in the book feel that it isn’t, and I think that Clarke, despite his professed rationalism, felt it too. Precisely because all of mankind’s material needs have been met, something in human beings that cannot be weighed or measured faces a crisis, a crisis that is beginning to make itself felt just before the children’s evolutionary change commences. Ambition, achievement, art, any kind of human aspiration at all, are all dying. Though the withering is just beginning, the more sensitive spirits (pardon the word) have a deep-down intuition that this will be the race’s greatest challenge, a life or death one, in fact.

The Overlords know, however, that it is a cul-de-sac that humanity will not be able to escape from — as human beings. In this, Childhood’s End differs from another cosmologically ambitious novel, Poul Anderson’s Tau Zero. In that book, men and women also fulfill an extraordinary destiny, but they fulfill it as human men and women.

For Clarke, this is just not in the cards. To survive at all (some early Cold War pessimism showing here, perhaps), the human race must transcend the limits of humanity, must, in fact, become divine (what is the Overmind but a God who never bothered to write a book?), and this cannot be achieved by any combination of good government and flying cars. It can only be achieved through an unexplained, in fact irrational, evolutionary leap. Why irrational? Well, need it be said that the scientific evidence for such a thing (grungy matter evolving into pure mind) happening, now or ever, or even for the barest possibility of such a thing happening, is, well… zero? Though Clarke would be loath to use the term, such a leap wouldn’t be only an evolutionary one; it could only be the result of the proverbial leap of faith.

Did Clarke really think such a thing was possible? There’s an odd little note, hidden at the bottom of the copyright page of my Ballantine paperback of Childhood’s End; I almost missed it. “The opinions expressed in this book are not those of the author.”

Now what can that mean? That the book is a joke, or nothing more than a coldblooded thought experiment, or an elaborate, abstract metaphor for… what? I’m not sure. I know that Clarke’s mystical, religious… temperament, impulse, however you want to characterize it, is something that’s not confined to Childhood’s End, though it finds its strongest expression there. It’s also present in The City and the Stars, 2001, and Rendezvous with Rama, to name only three of his other novels. It may have been only the manifestation of a walled-off part of himself that he didn’t fully acknowledge or understand, but it’s hard to deny the reality of something that’s expressed so fervently and consistently.

Whatever the ultimate meaning of his cryptic disclaimer, I was powerfully stirred by Clarke’s vision; as I am merely a single, transitory human being and not the entire race, and invested in my own little life and the lives of those close to me more than I am in any enormous, impersonal destiny, I found Childhood’s End to be an achingly, beautifully melancholy story; its solemn sadness has the cold, heavy weight of finality to it. It’s one of the most deeply-felt books I’ve ever read (an impression perhaps heightened by reading it in my sixties instead of in my teens), and within its limits, it’s what few genre science fiction stories even attempt to be — a work of art.

I’m very glad that I have finally rectified a long-standing fault and gotten better acquainted with Arthur C. Clarke. Indeed, I have come to believe that he may have been the best balanced of the giants of 20th century science fiction, more realistic and grounded than Bradbury, more lyrical and poetic than Asimov, and less dogmatic and more humane than Heinlein.

Whether or not we are forever stuck being only “human, all too human” (in the words of Friedrich Nietzsche, another denier who still yearned after transcendence — one man’s Overmind is another man’s Übermensch) it’s worth spending some time meditating on what that humanity consists of, what its boundaries are, and what ends it ultimately might be here to serve. Childhood’s End is a work perfectly suited to spurring and aiding those thoughts about our destiny.

But don’t wait fifty years to read it. “God” knows what might happen in that amount of time.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A (Qualified) Vindication of Lin Carter’s Fiction: Kesrick

Those Ballantine editions with the almost laughable hodge-podging together of the spaceships from “2001” were some of the first books I ever bought. I picked them up from the glorious mass market paperback racks of the family-owned drugstore that was on the walk home from junior high, running the rest of the way back to devour them in my bedroom. I imagine I wasn’t the only kid who lucky enough to have parents who took them to see “2001” and subsequently went on a Clarke binge in those chimeric years between late childhood and adolescence.

“Childhood’s End” by far made the biggest impression on me and to this day remains one of the rarest, most satisfying of reads, right beside “Watership Down.” Most of the appeal comes from, as you note, Clarke’s solid, uncluttered style and clear, narrative smarts that made him, along with Ben Bova, among the most enjoyably readable of science fiction writers back in the day.

More crucially, I think, it’s the way Clarke renders the story, particularly the ending, with an affecting mixture of awe and pathos that always colored his best work and here is pitch perfect. The only other writer who similarly moved me was H.G. Wells, at the climax of “The Time Machine” and in a short story (whose title I can’t recall but I’m pretty sure it was Wells) about an instantaneous evolutionary leap in human intelligence that affects part of the global population, leaving the remaining unchanged populace struggling to cope with the consequences.

Kurt Vonnegut considered “Childhood’s End” the one great science fiction novel and while many would challenge that sole distinction I find myself sympathetic to his take.

Thank you for a very fine article.

Clarke drew and draws his considerable power from being the great synthesis in the latter 20th century of, on the one hand, the earlier British Edwardian Engineer-Mystics like Wells, Stapledon, and Kipling (when he wrote SF) and, on the other, the American magazine SF that emerged with Campbell’s Astounding in the 1940s out of the pulps.

God knows it isn’t Clarke’s style or characterization. But when his synthesis of the two traditions — the British cosmic visionary and the Campbellian nut-and-bolts engineering worship — works, it’s powerful.

I have a very similar history with Sir Arthur, started by seeing his classic short stories in anthologies, then by reading Childhood’s End, an immediate purchase from Scholastic Book Services with that unmissable Dean Ellis cover of a giant saucer eclipsing an entire city. And I do get that weirdly mystical vibe from the novel, with the evolved human children expressing something like an “Oversoul”, which the agnostic, materialistic Overlords lack. Melancholic, yet not unhopeful. Of the Big 3 (Heinlein, Asimov, Clarke), I did like his writing the best. Maybe that stray metaphysical tone is what adds the right spice to the recipe (along with superior literary talent).

Clarke was one of my childhood staples, although on a lower tier than, e.g., Heinlein (Dad’s favorite) or Asimov. Most of the Clarke I read came from the library, but Dad did have paperbacks of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Tales from the White Hart (which had another one of those 2001 pastiche covers, which left me _very_ confused when I read it — there weren’t any giant, rotating space stations in the book!).