A (Qualified) Vindication of Lin Carter’s Fiction: Kesrick

Care to join me in a Pavlovian conditioned reflex experiment? Good. I’m going to ring a bell and we will observe your response. Ready?

Lin Carter. (That was the bell.)

Hmmm… exactly as I expected. At the mention of the name of the late fantasy editor, anthologist, and author, you immediately whispered, muttered, or shouted some variation of the formula, “His great knowledge and advocacy of classic fantasy, especially through his groundbreaking editorship of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series from 1969-75, means that every lover of fantasy owes him an immense debt, but his own fiction, primarily pastiches of Robert E. Howard and (especially) Edgar Rice Burroughs, is plodding and rote and not worth reading.”

Good boy! A tasty dog treat for you!

Your response to the Lin Carter stimulus came as no surprise to me because I’ve said much the same thing myself, many times, in comments every time he comes up here at Black Gate — which is fairly regularly, the last time being just a couple of weeks ago when the estimable Charles Gramlich gave us an overview of Carter’s several Burroughs-esque series. At that time, I posted a comment almost identical to the one above.

The funny thing is, as I also mentioned in that comment, I have all those Lin Carter books that I disparaged, and I’ve read many of those lifeless, by-the-numbers rehashes that he spent his time cranking out. (Another funny thing that no one pointed out, is that Donald A. Wollheim, who published most of them, was not running a charity; someone was buying those books.)

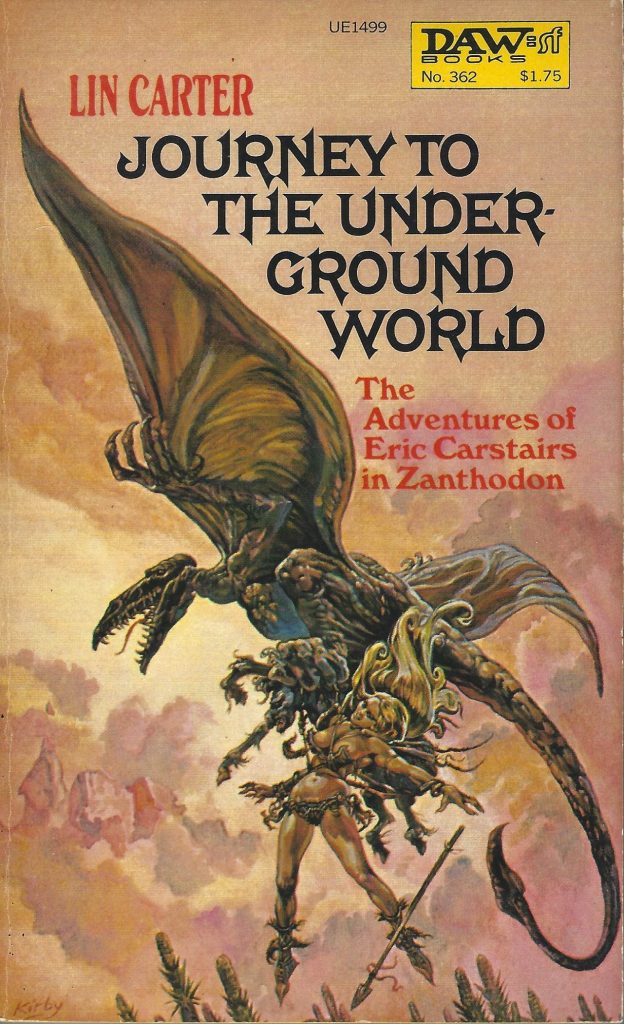

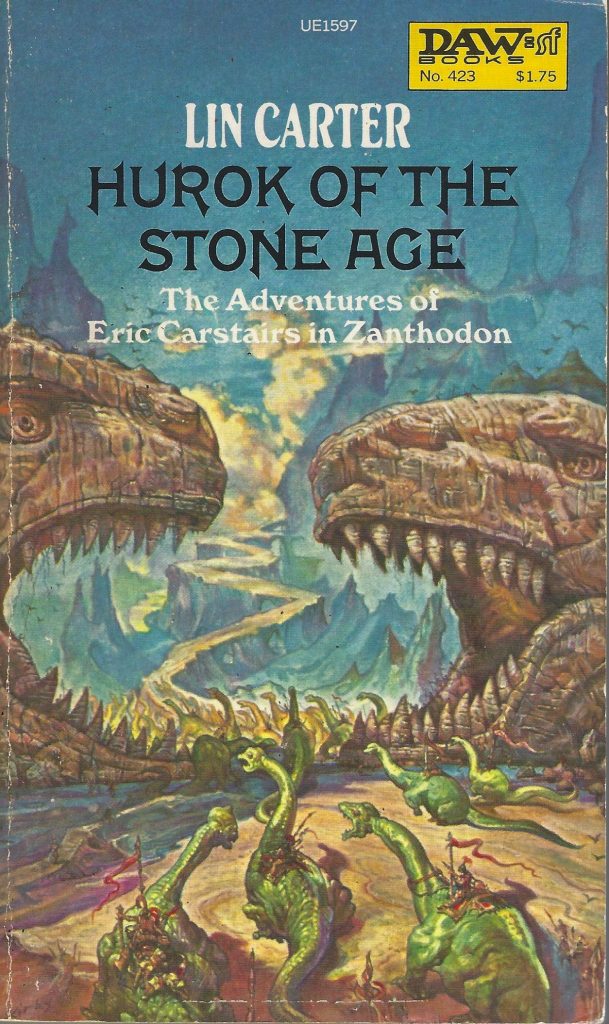

Though I’ve dipped into most of Carter’s pastiche sequences for a book or two, the only one I’ve read completely is his Zanthodon series, which comes across as a smudged carbon copy of ERB’s Pellucidar saga. Carter’s inner-earth series runs for five books, and I read it, a volume a year, over the course of five summer vacations, finishing with the last book only two summers ago. The books sport nifty covers by Josh Kirby (four of them, anyway), and I plunged into the first volume, 1979’s Journey to the Underground World, with high hopes for some good, Burroughs-flavored fun.

Well…

Burroughs at his best was an inspired writer, the greatest depicter of action who ever lived. (That’s not my verdict – it’s Gore Vidal’s.) Once you’ve read a white-hot ERB action set-piece, you never forget it — the slave rising in the arena of Issus in The Gods of Mars, Tarzan and Kerchack battling to the death in Tarzan of the Apes, every page of The Mucker, which is one wild, delirious brawl, chase, and hairbreadth escape after another — couple those with the man’s gift of exotic invention, pouring forth a never ending flow of glamorous and colorful flora and fauna and societies and languages… well, it makes Edgar Rice Burroughs an easy man to imitate (you can always see what he’s doing — it’s right there on the page), but an impossible man to equal or even come close to equaling, because those seemingly simple things that he was doing? First, they weren’t really that simple, and second, he did them better than anyone else ever did.

Lin Carter clearly deeply loved Burroughs, and so I don’t blame him for wanting more of the Master’s work, or even for thinking, “I see how he did it — I’ll do it too!” I don’t even blame him for churning out one pale, anemic Burroughs imitation after another, even when it became obvious that that sort of thing wasn’t really his forte. They certainly didn’t take long to write and you have to do something to pay the rent, right?

In this world, love, understanding, and forgiveness will only take you so far, though. (Lord, what a terrible thing to say!) That’s especially true when you’re reading a book that might be well intentioned but simply isn’t very good.

When I finished Journey to the Underground World, I thought, yeah, ok, what did you expect? But maybe it gets better. The next volume, Zanthodon, showed me the error of that way of thinking. No getting around it, that book is pretty bad. But volume three, Hurok of the Stone Age, has an absolutely awesome cover! The folks at DAW wouldn’t put a great cover on a mediocre book, would they? Yes. They would. Now the bloom was really off the rose; I knew that these books were stinkers and that the series was a waste of time. The thought of trudging through the final two books, Darya of the Bronze Age and Eric of Zanthodon, gave me no pleasure whatsoever; instead of looking forward to reading them, I actually dreaded it, because I knew that despite his passion for Burroughs, Lin Carter just wasn’t able to transfer any of that passion to the page. I could be certain that these books wouldn’t contain an ounce of juice, an iota of excitement, or a single surprise.

And that’s just the way it was, too, because though I may not be the deepest reader you’ll ever meet, I am one of the stubbornest. I started this series and I was going to finish it, by God, and finish it I did. At least you got a dog treat today; when I finished the Zanthodon series I didn’t get anything.

Which brings us back to where we started. As a writer of fiction, Lin Carter just wasn’t any good.

But is that really true?

Based on the Zanthodon series it is, and from what I’ve read of his Callisto series (read Barsoom) and his Green Star series (read Amtor — that’s Venus, you mugs, and for some reason slightly better than his other pastiches) and his Thongor series (I knew Conan, sir, and you are no Conan), the case against Lin Carter is open and shut. Bad writer. Off to durance vile.

But wait! The man was insanely prolific, and believe it or not, he didn’t only write pastiches of better, more original writers. He actually wrote what could be called his own stuff, too, but no one ever talks about those books. It’s not fair to consign Lin Carter to hard labor without at least taking a look at them, is it?

No. It’s not.

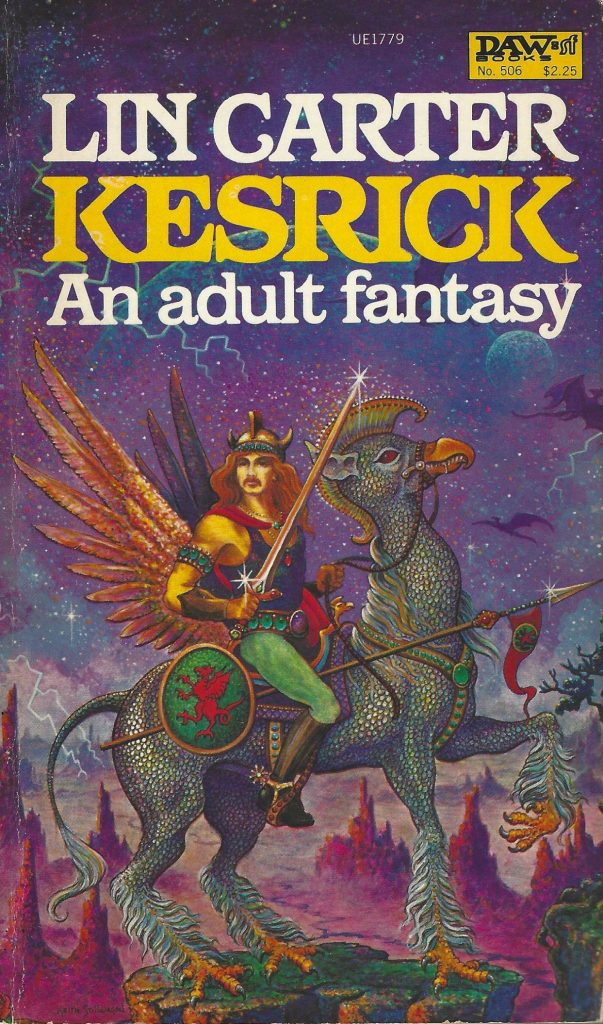

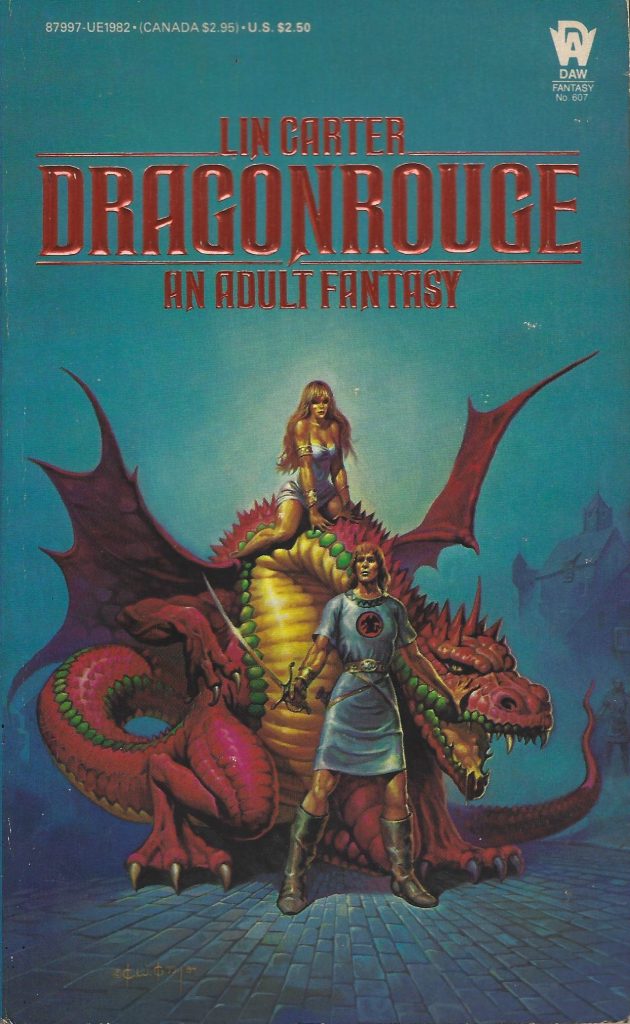

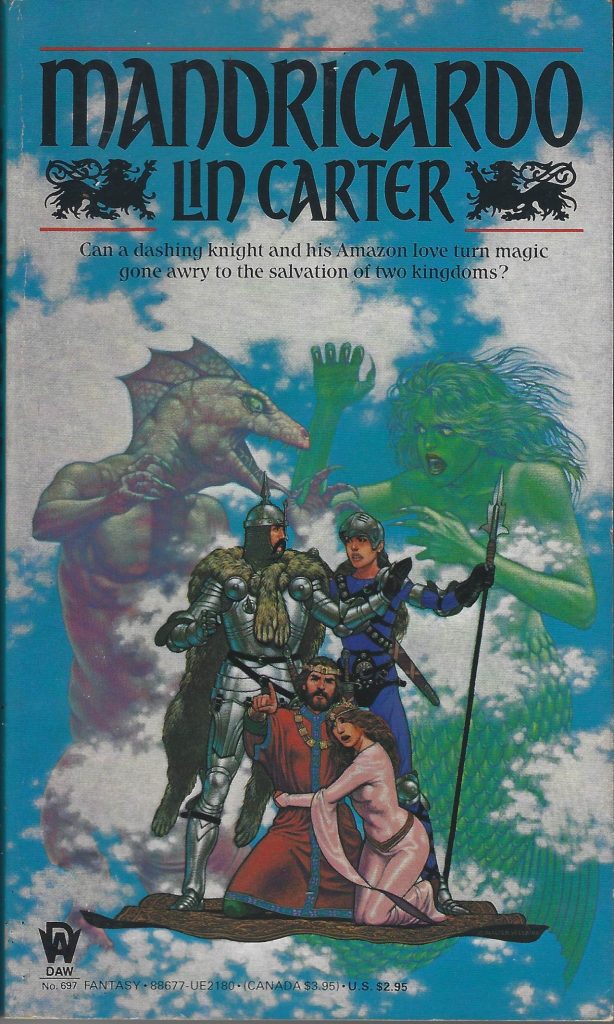

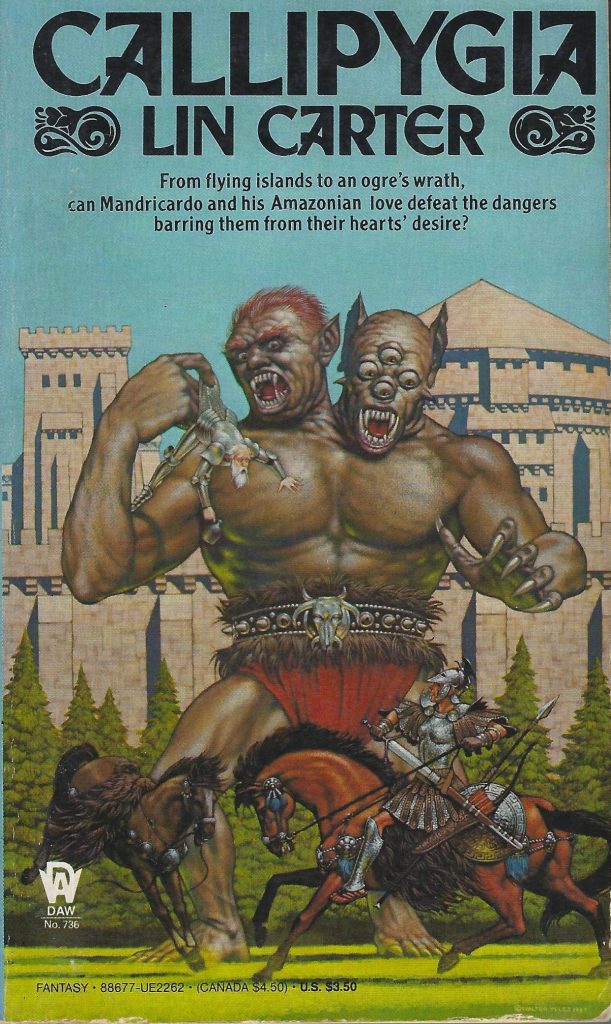

The last major series that Lin Carter started was set in his world of Terra Magica, and he completed four volumes before his death in 1988 — Kesrick (1982), Dragonrouge (1984), Madricardo (1987), and Callipygia (1988).

Therefore, we should begin our appeal of Lin Carter’s sentence sharpening the pencils of superior writers by reading Kesrick, which I have just done. In an author’s note at the beginning of the third book, Mandricardo, Carter says this about his imaginary setting:

Terra Magica is an alternate world, as close to our own as are the two pages in a book; so close that our most sensitive artists, dreamers, and poets glimpse something of its woods and fields, its tall cities and splendid heroes; thus, the history of Terra Magica becomes the substance of our epics and sagas, our myths and legends, fantasies and fairy tales.

In the indispensable Encyclopedia of Fantasy, John Clute puts it this way — in contrast to our mundane world of Terra Cognita, Terra Magica is “a land of vast proportions, an omnium gatherum territory which contains all the fantasies and legends told on Earth and theoretically in all the imaginary lands as well, giving Carter an attractive venue for his games of recursion.” As an aid to getting all of his playfully erudite references, Carter gives his readers notes at the back of these books, where he elucidates all of the myths, legends, extinct religions, fanciful geography and the like that fill the novels.

Kesrick (like all of Carter’s novels, it’s a book of modest length — 176 pages in my DAW paperback, no. 506) chronicles the adventures of its title character, Sir Kesrick, a noble knight of Dragonrouge, as he journeys forth on a quest to recover the enchanted pommel stone of his sword Dastagerd (“the Sword of Undoings”), which has been stolen by the evil Egyptian wizard Zazamanc, who had come across a prophecy which said that Kesrick would kill him, and sought to forestall this event by taking the stone that gave Dastagerd much of its power.

Along the way, Kesrick has colloquies with dragons, forms an alliance with the renowned sorcerer Pteron, rescues the Scythian Princess Aramaspia from a monster (she starts chained to a rock, naked, and never acquires any clothes through the rest of the book, occasioning a lot of wink-wink nudge-nudge over her physical attributes that would scarcely fly today), outmaneuvers a dim-witted efreet, Azraq (who had stolen the stone at the behest of Zazamanc), gets trapped in an enchanted garden, escapes from it, helps others escape from it (the Frankish knight Mandricardo, who speaks like an Edwardian twit — “Jolly good show, what?” — and the Amazon Callipygia — the notes tell us that her name means beautiful… uh, butt, in Greek) who then join him on his quest, gets trapped in Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged house, defeats the hungry witch (with the help of Dame Pirouetta, his fairy godmother — yes, you read that right), and eventually confronts Zazamanc in his forbidding fortress, and with the aid of Dastagerd and its restored pommel, turns the nefarious magician into stone. (Zazamanc threw a spell at Kesrick that would have petrified our hero, but the special power of the pommel is to turn any magic back on its user. Zazamanc knew that but he just… forgot.)

Whew! It’s certainly fast moving, but is Kesrick the work of “one of the finest fantasy writers of all time”? (The words of anonymous copy appearing on the cover of my 1969 Belmont paperback of Carter’s Tower at the Edge of Time. Don’t even get me going about blurbs…)

Well, I wouldn’t go that far. Kesrick has plenty of faults, many of them likely stemming from being written quickly with minimal revision. But I still enjoyed reading it; I thought it was fun.

No book is completely original, utterly uninfluenced by anyone or anything else. Carter dedicated this first Terra Magica novel to James Branch Cabell and Lord Dunsany, “perhaps the two greatest fantasy writers of us all”, while he dedicated Dragonrouge to T.H. White and Andrew Lang, and though you can see the influence of these writers in Kesrick, Carter isn’t attempting an outright imitation of any of them, which it’s a very welcome change, and while the book is peppered with the kind of Arabian Nights tropes and imagery that Carter loved, it’s not a do-over of Vathek or The Shaving of Shagpat, and if you’re someone (like me) who clawed their way through those books because Lin Carter recommended them, you’ll probably be grateful that their mark on Kesrick is relatively light.

If Kesrick reminds me of anything, it’s John Myers Myers’ Silverlock, with its land of the Commonwealth peopled by characters from fiction, history, legend and folktale, but I never felt that Carter was aping that odd novel (about which I have decidedly mixed feelings. Maybe it’s time for a reread.)

The tone of Kesrick is decidedly light and at times outright comic. Terry Pratchett’s first Discworld novel didn’t come out until a year after this initial Terra Magica book and only a few Discworld books had been published before Carter died, but at times it feels as if he was at least making a nod in the direction of the territory that Pratchett claimed and made his own. Pratchett was a far better writer, both as a fantasist and as a humorist (he was the P.G. Wodehouse of fantasy, and I can think of no higher praise), but now and then Kesrick reminded me of Sir Terry, and in a good way.

Ultimately, what was most enjoyable about Kesrick was simply not knowing what was going to happen next. The openness of Carter’s premise and the helter-skelter, willy-nilly, grab bag nature of the realm itself separates it from his Burroughs and Howard productions, which usually feel stenciled rather than written, copied instead of created. But in Terra Magica, any damn thing can happen, and I found being even mildly surprised a new and welcome sensation, one that I had never before experienced when reading a Lin Carter novel.

In the end, Kesrick was not a masterpiece, not a towering work of the imagination, not a great book. But as a fantasy-flavored, freewheeling romp not beholden to anyone in particular, it was by far the best Lin Carter novel that I have ever read; like even his bad books, it was manifestly the work of a man who was fearsomely knowledgeable about fantasy, and who loved it more than anything in the world, and unlike his pastiches, it felt like it belonged to him; it was his in a way that the Zanthodon and Thongor books just aren’t.

It makes an enormous difference. When I dragged myself to the bookshelf to fetch my copies of Darya of the Bronze Age and Eric of Zanthodon, I did so with all the enthusiasm of someone going to the dentist for a root canal; I just wanted to get it over with.

Next summer, though, when it’s time to read Dragonrouge, I’ll actually be looking forward to revisiting Terra Magica and seeing what Lin Carter is going to do with his magical land and his silly but likeable characters. (The cover of Callipygia leads me to believe that eventually the crew will meet up with none other than Don Quixote himself, which should be quite a treat.) I’ll be happy at the thought of spending a few days, not with a sort of literary laser printer, but with a… dare I say it?

Yes. I’ll be looking forward to spending my time with a writer, one worthy of a little more respect than I (and probably many of us) have heretofore given him.

I just love a happy ending!

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Don’t Leave Earth Without It: Bill Warren’s Keep Watching the Skies! American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties

Those of us who were around for the seventies know exactly what I mean when I say, “Van art.”

Hmm. Myers’ “Silverlock”… I have that one, and I think I enjoyed it…? And that it struck me as something along the lines of Robert Aspirin and Piers Anthony in terms of zaniness… I think. 🤔 There’s a lot of mental sludge atop that book, as far as a comparison goes.

Still! It’s good to read a positive recommendation of some of Lin Carter’s work! As much as his naming conventions are going to make me groan, I like a good Edwardian twit and the “Callipygia” cover encourages me to think that the women other than the Fairy Godmother may develop into actual characters. So this series will be added to the TBR pile (which will be able to take it because I’ll shortly be through the “Carbonel” set).

Good article. 🙂

I wonder why the sub-heading “an adult fantasy” on two of these books (from the 1980s apparently). Were the marketing folks of the opinion that everyone thought of fantasy as a genre only enjoyed by kids? Or were they using “adult” as a way of implying “like a kid’s fantasy but with sex”? It seems like an odd locution for an era when there had already been quite a few inappropriate-for-kids fantasies published (Jane Gaskell was the 1960s, for one). Of course, now it’s totally superfluous since there are no adults left in western societies.

I’ve assumed that it was just a way of trading on Carter’s fame (such as it was) as editor of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. As I said, there’s a good deal of low-voltage ogling of Aramaspia’s endowments in Kesrick, but there’s nothing that even approaches actual sex.

This is a fantastic article, Tom! I first read Lin Carter in 1968 or 1969, when I was in my late teens. I had already devoured ERB , so I got into Carter and enjoyed many of them. He had a great imagination and a pretty good knack for writing prose. But what he lacked was good dialog, depth of characterization, real human drama and interaction — much like ERB. He never really pushed himself, prolific though he was. His Green Star and World’s End series are my favorites. Sadly, I grew bored with him by the time I was in my mid-20s. I tried to re-read him several years ago but could not get through any of them. I hope to re-read ERB’s Pellucidar series, but am afraid I won’t get through it. Anyway, for me, Carter’s real legacy lies in introducing me to past masters of the pen and many (at the time) new writers. He played a role in fostering and nurturing Heroic Fantasy and Sword & Sorcery, so for that I am grateful to him, may he RIP.

I’ve returned to ERB from time to time, Joe, and as long as you’re not expecting him to be Chekhov (Anton, not Ensign) I think his best stuff holds up pretty well. I’ve been thinking of rereading the first two Pellucidars myself, as I remember them as being peak Burroughs. We’ll see; I read Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar for the first time a few years ago and enjoyed it quite a bit.

I always enjoyed Lin Carter’s work even as I recognized most were derivative of ERB or REH. He always entertained. Of the many I’ve read THE MAN WHO LOVED MARS is a standout.

I am embarrassed to confess that after a certain point I started buying Carter just for the introductions, even of his own books… Man, could he write an intro!

Of the Terra Magica series I think the only one I read straight through was Mandricardo, which I … didn’t hate. What did annoy me was that he didn’t bother linking his endnotes to the places in the text they connected to, something he always did (when he had endnotes) in his earlier writings. If you encountered something in the text you were curious about, you might flip to the back to SEE if there was an endnote about it, but as often as not, there wasn’t. Though there might well be about something you hadn’t needed a note about. If you like the Terra Magica books, you might also try The Wizard of Zao and the Gondwane series. Similar flavor.

My record on his other series is similar. From Thongor I mostly remember Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus, and that spoof essay in one of the others on where he got the overall plot for that series from, which was totally entertaining and completely fooled me (it was supposedly a Hindu holy book or epics that does not in fact exist).

From the Green Star books I only got through the first, Under the Green Star. Managed a couple of the Gondwanes, the first of the Zanthodons.

But all of the Callistos, which I mostly liked (one cannot like Lankar of Callisto, however much one tries), and all of the Mysteries of Mars series, ditto, even though the latter all had the same plot. (Incidently, the very best Mysteries of Mars novel I’ve ever read was actually Immaculate Scoundrels, by John R. Fultz, which was not set on Mars at all, but also had that same plot!)

And of course I read Tara of the Twilight because I was in my late teens, and it actually had sex in it. Um, yeah, every kind of sex except the basic kind, because Tara’s goddess-given strength was dependent on her remaining a (technical) virgin. Incidentally again, has anyone else noticed that Carter seemed to have an unhealthy fixation of pubescent boys? Hopefully only in his writing…

All in all, yes, Carter was better writing ABOUT fantasy than he was writing fantasy. His fiction was uneven. But not all bad.

With Kesrick, I read the notes before I read the chapter – the chapters are short enough so it (usually) hadn’t all run out through my ears by the time I got to whatever Carter was referring to!

I overall like Mr. Carter and his multitudinous contributions to our favorite genres, and I can even praise him for several of his endeavors, like the Flashing Swords series, though Betty Ballantine would frown if I mention Mr. C as other than the “editorial consultant” of the magnificent Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. (Those cover illustrations!)

On the fiction side, I have only read his Green Star series, and that one backwards, as I stumbled across In the Green Star’s Glow first, and then looked for its predecessor. I would agree that his writing goes along better when it is mixed with some humor. The Amalric the Man-God stories he put into two of the Flashing Swords books were disappointing only in that he never continued the saga beyond the two. I probably should have snapped up the Terra Magica books, especially considering I have enough of a Classics background to know what “Callipygia” means.