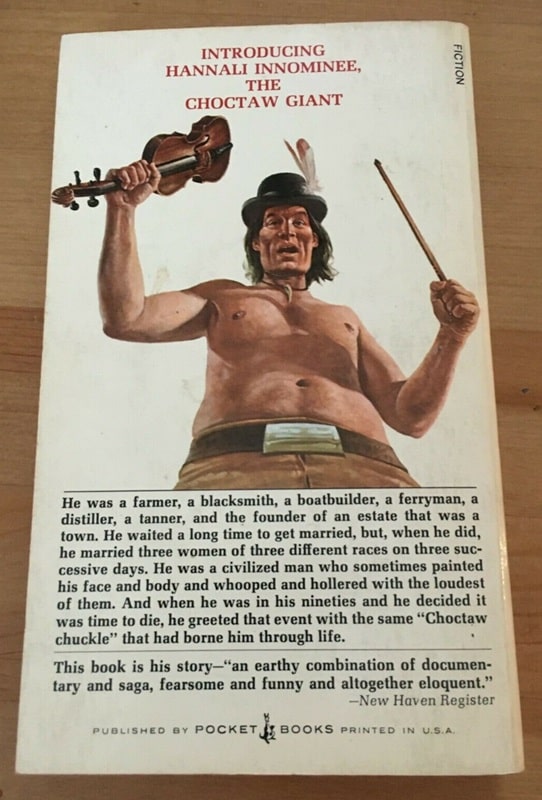

Daughter of DAW: An Interview with Publisher Betsy Wollheim, Part II

This interview was transcribed from a Zoom meeting of the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society on June 14, 2024, conducted by Darrell Schweitzer and hosted by Miriam Seidel.

Read Part I here.

Darrell Schweitzer: The other factor that must go into accepting a book for publication is that the editor has to see how the company can make money off the book. I have heard of books being turned down with a response, “This is perfectly charming, but I don’t see how we can publish it profitably.”

Betsy Wollheim: Usually a publisher has a few really big authors, so they can afford to publish a book that is brilliant, but may not be commercial. That was really my father’s attitude toward the Gor books. Ironically, John Norman enabled him to publish Suzette Haden Elgin, a feminist author. Patrick Rothfuss sells a lot of books — he’s an outstanding writer and his sales enable us to publish books that might not sell that well, which is lovely.

You presumably buy them on the hope that eventually they will sell more.

Of course. If I like it, I assume other people will like it.

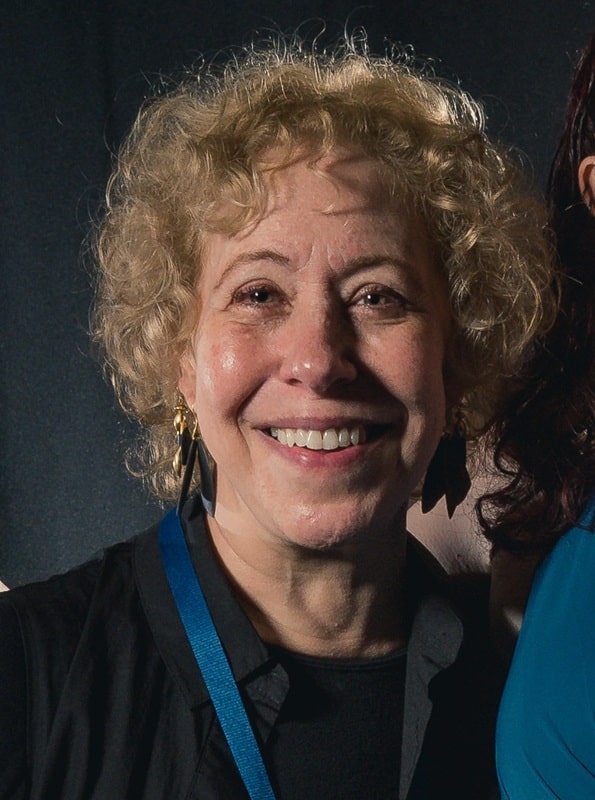

There are still writers like R.A. Lafferty who will never be commercial.

No, R.A. Lafferty is brilliant. He is a brilliant writer. Okla Hannali is one of the most brilliant books I have ever read. I think my father called it the “Kate Wilhelm Syndrome.” Brilliant writer, fabulous books, don’t sell. Why? We have no idea. This does happen and it’s really mystifying.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

|

|

Okla Hannali by R.A. Lafferty (Pocket Books, July 1973). Cover by Alan Magee

Anything by Lafferty will sell in the small presses at five hundred copies. I don’t think there has been a commercial edition in a while.

I wonder if R.A. Lafferty should have published as mainstream.

It may be that the mainstream editors didn’t have the insight to appreciate him.

I think that now, science fiction is crossing over into mainstream. Back then it really didn’t. But I think Lafferty would have been better served by a mainstream publisher.

You mean make him Oklahoma’s Thomas Pynchon.

He is a terrific writer.

Well I’m a fan, but I had to acquire all these strange little editions.

Yes. It happens. That is why it is good that more people are self-publishing. It means more books are out there. More voices get heard. If they do succeed, a publisher will usually pick a book up.

There are enough small publishers out there who will publish a book without the author doing it or charging the author to do it. They may not pay advances, only royalties, but they’re out there.

I have never published a book without giving the author an advance.

|

|

|

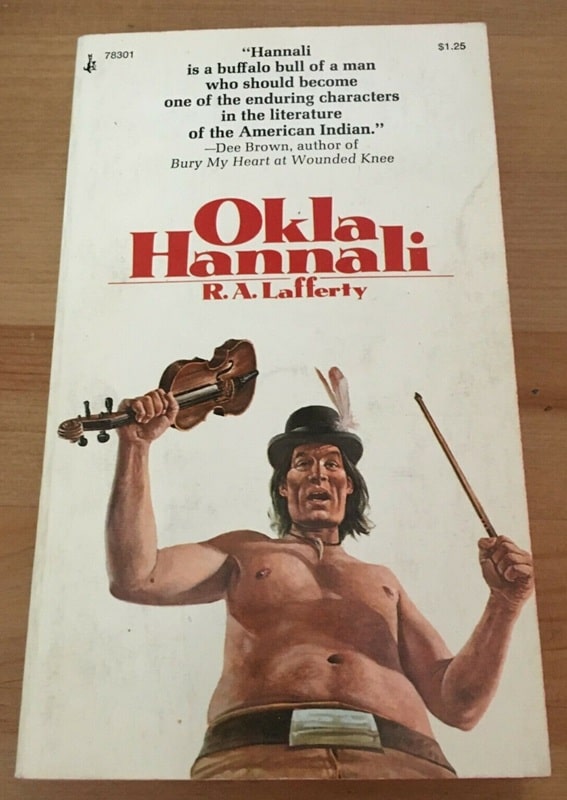

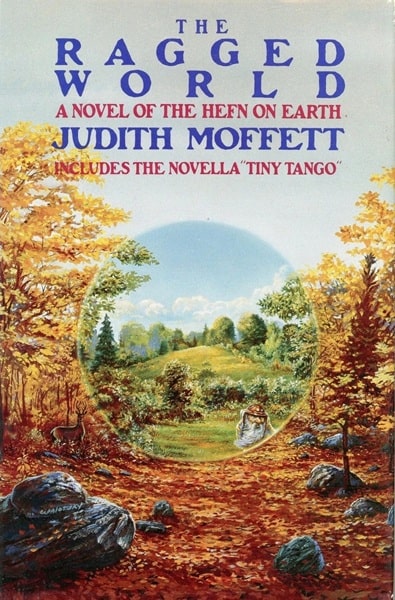

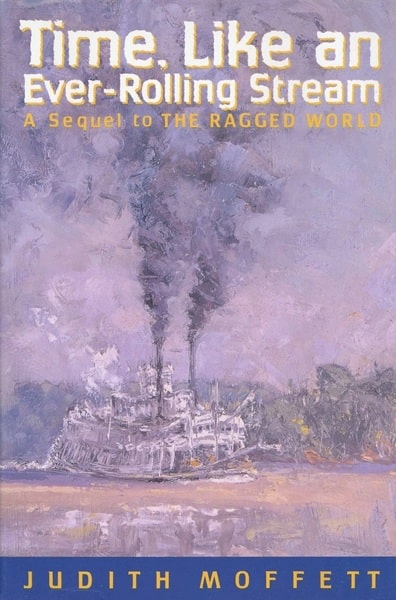

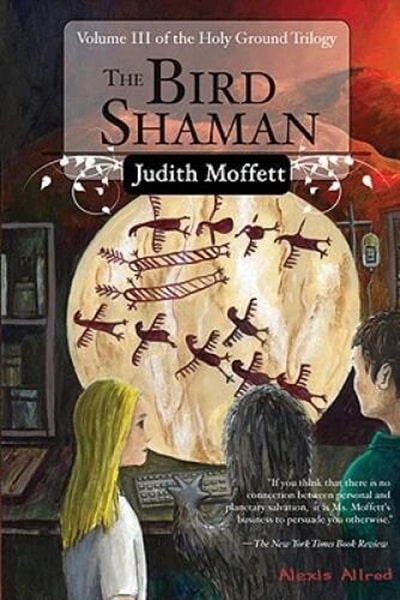

The Holy Ground Trilogy by Judith Moffett: The Ragged World (St. Martin’s Press, February 1991),

Time, Like an Ever-Rolling Stream (St. Martin’s Press, September 1992), and The Bird Shaman

(Bascom Hill Publishing Group, July 15, 2008). Covers by Ron Walotsky, Harlan Hubbard, unknown

That is because you are at a more commercial level. But the advantage of these small presses, at least is that it didn’t cost the author a dime. You may have seen an article by Judith Moffett in The New York Review of Science Fiction a few years ago. She had a book which was the last book of a series. The first one was published by St. Martin’s. I think it won a Nebula award. But nobody would publish the last one at a commercial level. Unfortunately she didn’t go to, say, Wildside Press, which would have published it for free, but she went to a vanity publisher, who ripped her off for about $7000 of ridiculous fees, and then they sold about 125 copies. If she had known what she was doing she could have sold 125 copies and it wouldn’t have cost her anything. There is a level of small publishing above the level of vanity publishing, which can be a safe haven for an author in that situation.

Yes. Vanity publishers do not have my respect, quite honestly. Small publishers do have my respect.

You can all tell that a self-published book is dead in the water if the front-matter is in the wrong order, as if no one involved ever looked at a real book to see where the title page and the copyright page go. A book designer friend of mine, an artist named Jason Van Hollander, has a one sentence course in book design, which goes: “Take a book from a nice conservative firm like Knopf and copy it.”

Question from audience [Miriam Siedel]: So, Betsy, when you started as editor of DAW, were you like the only woman at the time and did you have trouble in that space getting the respect you needed to do your job? I assume that has changed, but if you’d like to talk about women in the industry as publishers, editors, or writers, please do.

Betsy Wollheim: It’s interesting. I was certainly not the first woman editor. Betty Ballantine was the first long-form editor in our genre. People seem to blank out on her. They don’t realize that she edited science fiction and fantasy in the ‘50s and ‘60s. She was the editor, not her husband, Ian. She bought a lot of my father’s authors. My father used to say he should be on her payroll, because my father would find someone and publish them, establish them, and when they were well established, Betty would poach them by paying slightly more than my father had in his budget. She and Ian owned the company, my dad did not own Ace. Robert Silverberg is a perfect example. Bob and I are friends so he knows that I feel this way, but he basically said to me, “I was publishing with Ace and getting x-amount of money, and then Ballantine offered me $500 more. In 1963 that was a lot of money.” That was how Betty Ballantine got the giant science fiction list, by picking up my father’s writers.

Siedel: So she paved the way for you.

Betsy Wollheim: Kind of. I think my father paved the way for me.

Did your mother do any of the editing?

No, she wasn’t an editor. She handled all of the business. My grandfather was a jeweler, my mother’s father, and she ran his jewelry business, and then she worked for a law office in the 1930s and into the ‘40s. She was what they called a “law stenographer,” what’s now considered a paralegal. So she handled all the business. She would type up the contracts. She dealt with the royalties. All the business of DAW.

|

|

|

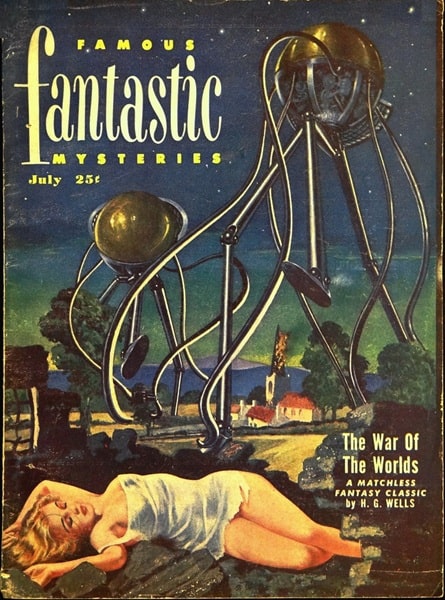

Famous Fantastic Mysteries, edited by Mary Gnaedinger: June 1945, June 1949, and July 1951. Covers by Lawrence

The earliest women editors I can think of in our field were magazine editors. Mary Gnaedinger, for example, who began Famous Fantastic Mysteries in 1939.

One of the agents I deal with now was originally the editor of Asimov’s, Shawna McCarthy.

I remember when she was hired. I was working on Asimov’s then, for George Scithers.

I’ve known Shawna since the 1970s.

There was also Dorothy McIlwraith, who began editing Weird Tales in 1940. She did a fine job.

I am sure that unlike Gernsback, she actually paid the authors.

That was one of the secrets of publishing. If you pay the authors, you don’t get sued.

My father sued Gernsback after non-payment of his first published story.

That’s pretty bold.

My father was that way. He was a fighter. He actually won a startlingly large settlement (for the time) of seventy-five dollars for a group of authors who had all been stiffed. He then submitted another story to Gernsback under a pseudonym, and was once again stiffed. Gernsback didn’t care if he was sued. He would settle the suit and then continue to not pay people.

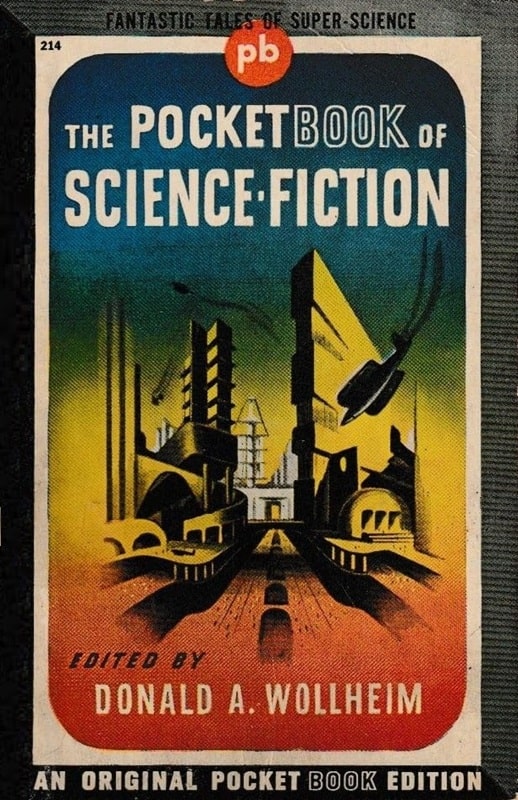

There was a woman lawyer named Ione Weber in those days, who specialized in Gernsback debts. Many authors used her. Did you father go to her?

I don’t know.

It was well-known in the field in those days that you had to sue Gernsback to get paid. It was a regular thing. But they never had to sue Weird Tales. One of the things I’ve learned in publishing is that if you can’t afford to pay people, you should tell them. Don’t stonewall. Farnworth Wright would write these pleading letters about how bad business was and promise to pay when he could. Gernsback wouldn’t answer. This built up an adversarial relationship with his authors.

That was bullshit. Gernsback was paying himself $100,000 a year. A huge salary for the time.

It was bullshit from Gernsback. But Wright was never sued.

It is really kind of horrible that we’ve named our greatest award, the Hugo Award, after a man who stiffed his authors. They cancelled Lovecraft because of his racism. They cancelled Campbell because of his politics, but Hugo Gernsback seems to be untouchable.

Lovecraft is more popular than ever.

But the World Fantasy Award got changed and is no longer a bust of Lovecraft.

It did. It’s just as well that we don’t remember a lot of the other writers of the period. David H. Keller, for instance, would be in the Rush Limbaugh/Donald Trump camp today. He was really something.

Question from audience: Betsy, there was a woman whose name I have forgotten, who really blasted Campbell for his racism, and you came out in support of her. You said “My dad used to go on about him being racist,” so bravo to you.

Betsy Wollheim: My father hated Campbell, for political reasons. He said Campbell was a fascist. So when Jeannette Ng said what she said I was thrilled, “Yes! Finally!” I didn’t know anyone had seen that. I am glad you saw that.

Are you talking about the woman who had a tirade that was nominated for a Hugo?

Miriam Siedel: She had won the Campbell Award, I think.

Betsy Wollheim: She [Jeannette Ng] won a Campbell and she went up there and said “John Campbell was a fucking fascist,” And I thought: “Yes! Yes!”

John Campbell was also the foundation of 20th Century science fiction. Sometimes you have to separate someone’s work from their politics. Wagner wrote great music but was quite an asshole.

Betsy Wollheim: That’s the whole debate of whether you can or should separate the art from the artist. Picasso was a horrible person. Does that mean his art is no good? I really do think that art should stand by itself and not be influenced by the personal opinions of the author. That is my definition of art. But this is a much debated subject.

I recall that Isaac Asimov once said that John Campbell was his literary father and after a while he wanted to leave home.

Isaac was the only one of the big three – Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke – that I knew very well. He was sixteen when my father and Fred Pohl founded the first group of science fiction fans [the Futurians] who would live together and work together and write together and publish things. He would come up to their Brooklyn apartment every day and be so obnoxious that eventually they would just throw him down the stairs. They were all ten years older than he was. He was just a teenager. My father said he was the only one who had to grow into his ego, because he was as egotistical at sixteen before he had ever achieved anything as he was later in life. Later in life it was fine.

I have heard stories like that about the young Ray Bradbury too.

I didn’t know Bradbury well.

Your father was also one of the great founders of 20th Century science fiction in many ways.

He’s also been forgotten by most people.

|

|

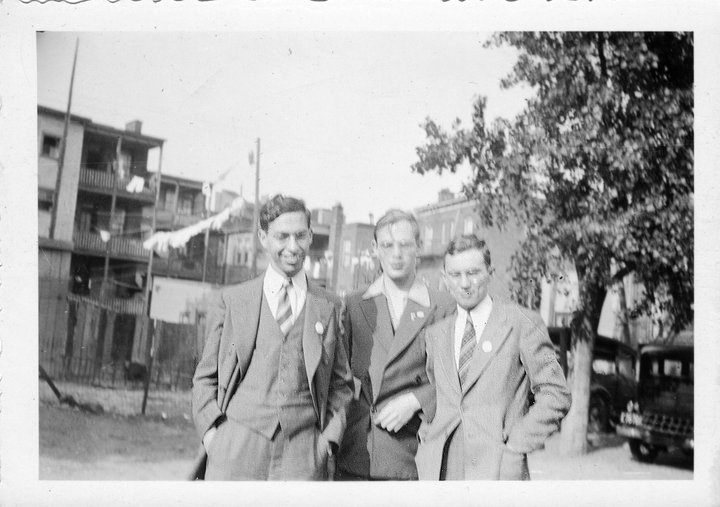

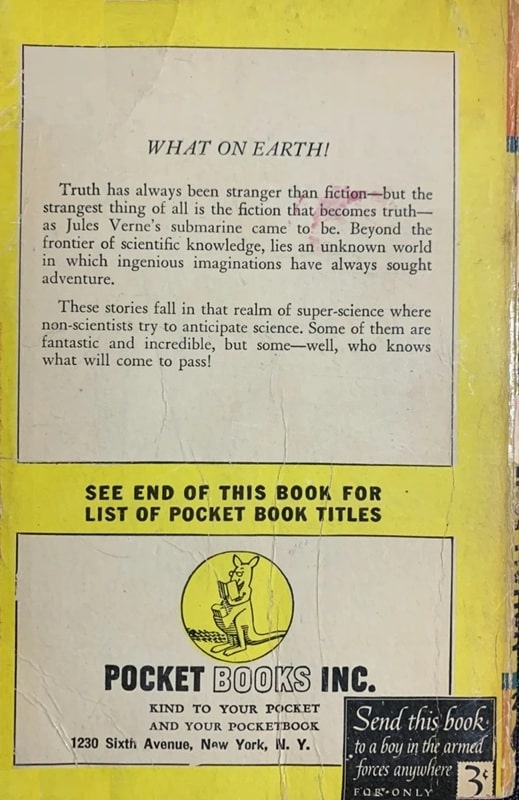

The Pocket Book of Science Fiction edited by Donald A. Wollheim (Pocket Books, March 1943). Cover uncredited

Not by book collectors. He edited the first anthology that was called science fiction, The Pocket Book of Science Fiction.

The title was painted onto the painting. Also on the spine. I have the painting. It’s very charming.

He also invented the Ace Double, which gave a lot of people their first chances.

That’s how he introduced new authors, by pairing them with somebody who sold really well. That was the basic idea. You pick a new author and put them with someone really established, and then the new author would ride the coat-tails of the established author in an Ace Double.

|

|

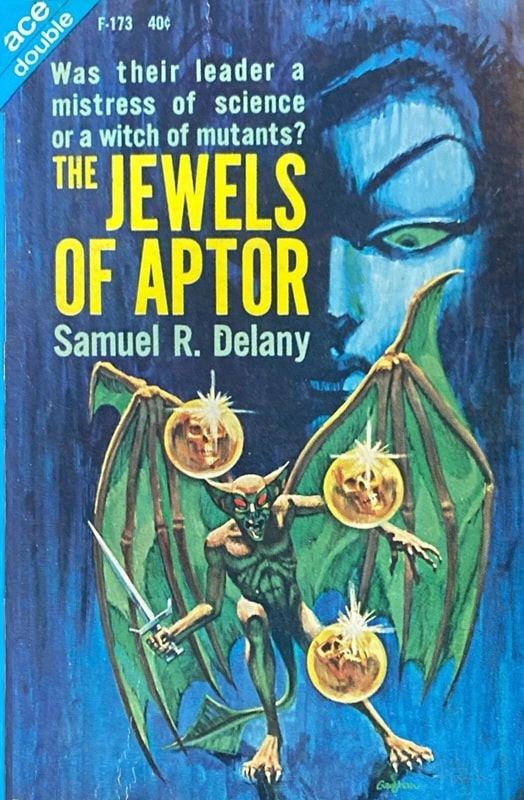

Ace Double F-1733: The Jewels of Aptor by Samuel R. Delany, paired with Second Ending

by James White (Ace Books, 1962). Covers by Jack Gaughan (left) and unknown

Nowadays it can be reversed, as when you find Samuel R. Delany on the back of a book by James White. White is an author of merit, but he is not remembered all that much.

I think that Chip Delany was the only person that my father ever called a genius.

What did your father think of Philip K. Dick?

My father was the one who first published his novels.

|

|

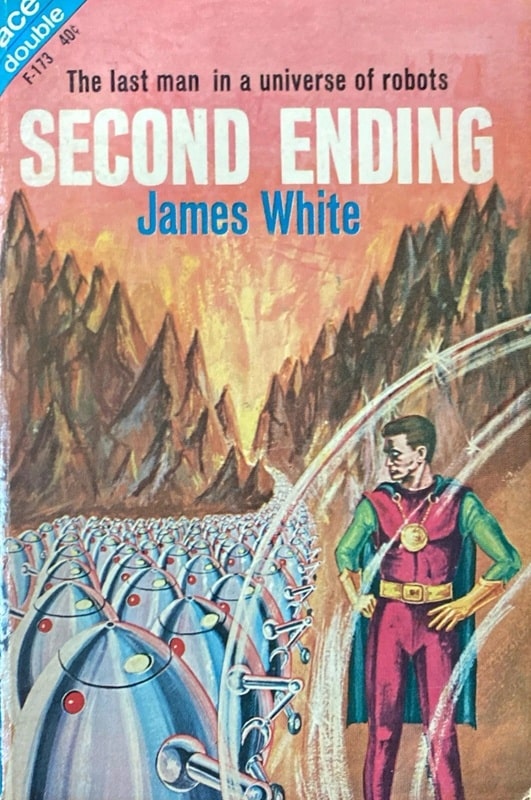

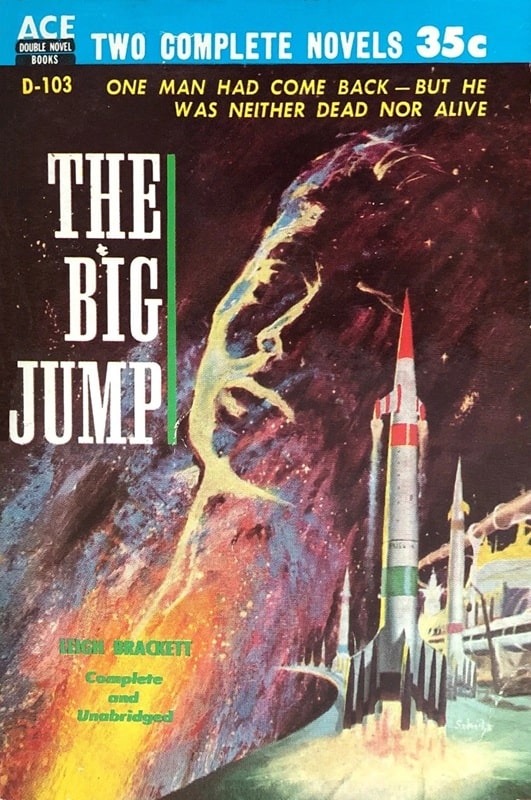

Ace Double D-103: Solar Lottery by Philip K. Dick, paired with The Big Jump by

Leigh Brackett (Ace Books, May 1955). Covers by Ed Valigursky and Robert E. Schulz

Yes, the first Dick book was Solar Lottery, which was half of an Ace Double.

He published him again at DAW, except Judy-Lynn Del Rey took Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Dick was also a notably eccentric character.

He was a very lovely, self-effacing man. He was a very sweet person.

Did you know him in the period in which he was having visions?

I only knew him in the ‘70s.

It was the late Philip Dick who was having visions and was convinced the FBI had blown up his safe. It got very strange at times.

Phil used a lot of drugs, as I recall. Not when I saw him, but earlier.

Question from Lee Weinstein: Did you attend meetings of the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society?

No. I just hung out with Philadelphia fans at conventions and at Lin Carter’s house. The thing I remember about science fiction conventions the most is that they were really small. Two thousand people was astronomical at Worldcon. When I went to my first convention at six, I also remember that there were almost no women. I was very little so I remember a lot of men’s black shoes. It was in three rooms in the Hotel New Yorker right across from Penn Station, in the Sky Top Room. Conventions were small. And mostly men.

I can remember Philcon being in one room. It was run like a big meeting. The chairman’s job was to be master of ceremonies and introduce people and get them on and off stage, and the audience sat there for single-track programming, and that was it. There was one row of book-dealers along the back wall. I was told at the first convention I ever went to, the 1968 Philcon, that that was the first time they had ever done that. It was in the basement of the Sylvania Hotel. I must have had a glimpse of the way conventions used to be. Conventions were like that for a couple more years, and then they got larger.

Much larger. They’re just enormous.

Question from audience: You’ve mentioned that you are not seeing AI written submissions, but how have Artificial Intelligence developments affected artwork and book covers? Does DAW have a policy on that?

Betsy Wollheim: We haven’t really defined it, but we do use images gotten on Getty or Shutterstock or any of the big photographic houses. I am sure most of those images are manipulated. So, the manipulation of images goes way back before AI. Some of the images we use from stock houses might be AI, but when we work with an artist directly, we assume that the artist is actually painting the painting.

Question from audience [Elektra Hammond]: The stock houses involve artists manipulating the photograph. The issue with AI is that if you use one of the big AI engines to make a picture, you don’t know who really owns the copyright, and that’s going to come up. If you go to Getty Images you can buy the rights to the image, and you know you own the right to use it. That is the difference right there.

Betsy Wollheim: I went to art school a long time ago, so I can understand what the problem is.

Elektra: It is the same with AI writing. They stole a lot of stuff on the Internet without permission, including pirated novels, to educate their AI engines.

Betsy Wollheim: It is scary and it is going to get more scary in the future.

Miriam Siedel: I understand there are more AI images on the stock photo sites now. I was looking for something recently to send somebody just an idea, and it looked so fake that it was really sad to me. Somebody probably just put a prompt in, and they got it and they submitted it.

Also, because no human intelligence is involved at all, you might see a group photo where the number of heads and pairs of feet don’t match and other ludicrous errors. I particularly like the one of Donald Trump praying in church and he is facing the wrong way and he has six fingers on each hand. This is why I should think that a publishable AI novel is an impossibility.

Betsy Wollheim: I don’t know.

It would totally lack personality or original outlook or a unique voice.

Siedel: It’s impossible, but it’s appearing on Amazon right now.

Betsy Wollheim: I also see things like [makes “quote mark” gesture] The Complete Work of Tad Williams and it’s twelve pages long, because it’s just reviews of books he published. That’s also on Amazon.

That’s an old form of Internet ripoff. It has been around for quite a while.

Betsy Wollheim: It definitely predates AI.

It purports to be the complete works but it is really whatever they could find in the public domain online, and they print it as a cheap POD book and sell it to you. It is a form of mail fraud, but you can’t sue them for it.

Back to Getty. About using Getty or Archangel or Shutterstock, usually there is a name associated with the image. So, I feel, if there is a name associated with the image, it is probably a human who has manipulated it themselves.

Way back when, J.K. Potter manipulated images right on the photo negative. He wasn’t even using a computer. You can tell that there is an intelligence and sensitivity in the result, where AI is mindless.

So we think, but ten years from now we could be changing our tune. It’s only going to get more and more difficult.

From audience [Terry Graybill]: It could be three years from now.

It could be three years.

Graybill: I find we are talking about a whole series of the scale of manipulation. Photoshop, when you remove the telephone pole behind the head in a good shot, is that bad manipulation?

No.

Graybill: It’s just improving an image without really changing it, like shooting through cheesecloth, which was done for years with celebrities to hide the signs of aging. Are we manipulating, yes, but it is within a familiar range. Think of what portrait artists do. They don’t put in every wrinkle unless they are going for a particular style of art. They give a flattering portrait. I am sure Darrell can cite any number of examples of this in ancient Roman art. It is not exactly new. So it is done to emphasize or de-emphasize or blur, to create an effect. Creating an effect is a form of artistry. Where does it cross lines? When you are using as reference material something someone else did and you are using it without permission and without paying them for it. It’s a very slippery slope. Where is the line?

Betsy Wollheim: I think you did it. You’re a human. That’s how you judge these things. If you feed it into a computer program, that’s a whole other thing.

Graybill: We have the problem, if I stole it, that’s a different level of stealing, or the computer device stole it. Neither one of us paid the original person for it. I feel strongly about protecting humans. But I also see where AI stunts creativity. It takes away something of the human spirit if we are simply using something generated for us and we no longer have to create it ourselves.

|

|

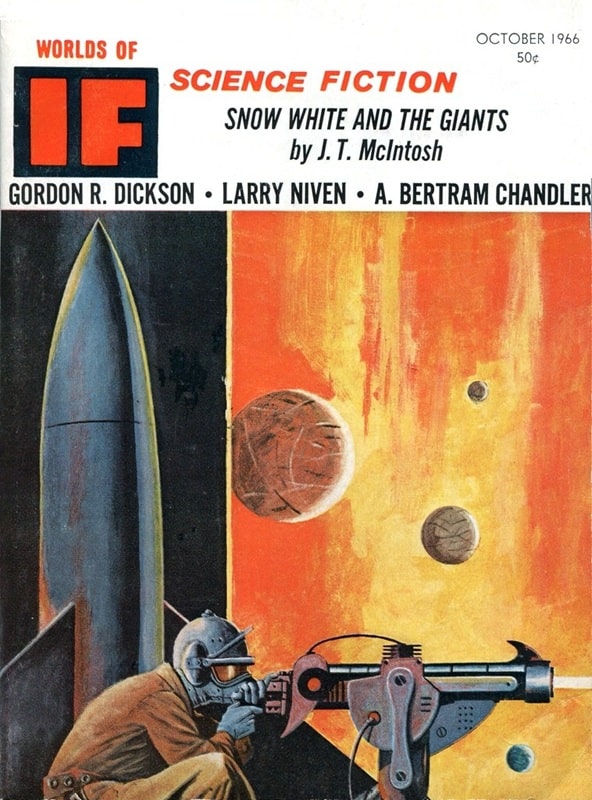

Art by Dan Adkins for Worlds of If: Cover for the October 1966 issue, and interior art

Art plagiarism is much older than AI. Does anybody remember an artist named Dan Adkins? He was a student of Wally Wood, but he became notorious for swiping the work of other artists, taking SF magazine art and using it in comic books and vice versa. You could look at something he did in an early issue of Creepy and say, “That one comes from a Galaxy cover, and that one is from F&SF.” I remember a two-page spread he did in Worlds of If which consisted of two recognizable Frazetta drawings spliced together with virtually nothing added. So you didn’t need a computer program to steal artwork.

Betsy Wollheim: I’ve been a friend of Michael Whelan since he came on the scene in the ‘70s. My father gave him his first job. Michael and I are the same age and we have been friends for decades. He has been plagiarized more than anybody except Frazetta. When Michael gets plagiarized overseas, it is hard to sue somebody overseas. It is very difficult. It’s expensive. At a certain point it becomes not worth it, but it has been happening forever. It’s really disturbing.

My father found a book that was submitted to us in the late ‘70s that was a complete plagiarism, word for word, of a book that was published in the 1930s, that I would never have recognized. My father knew it. He wrote to every publisher he knew and said, “Watch out for this person. Watch out for this book. This is a plagiarism.” He wrote to every single editor and publisher.

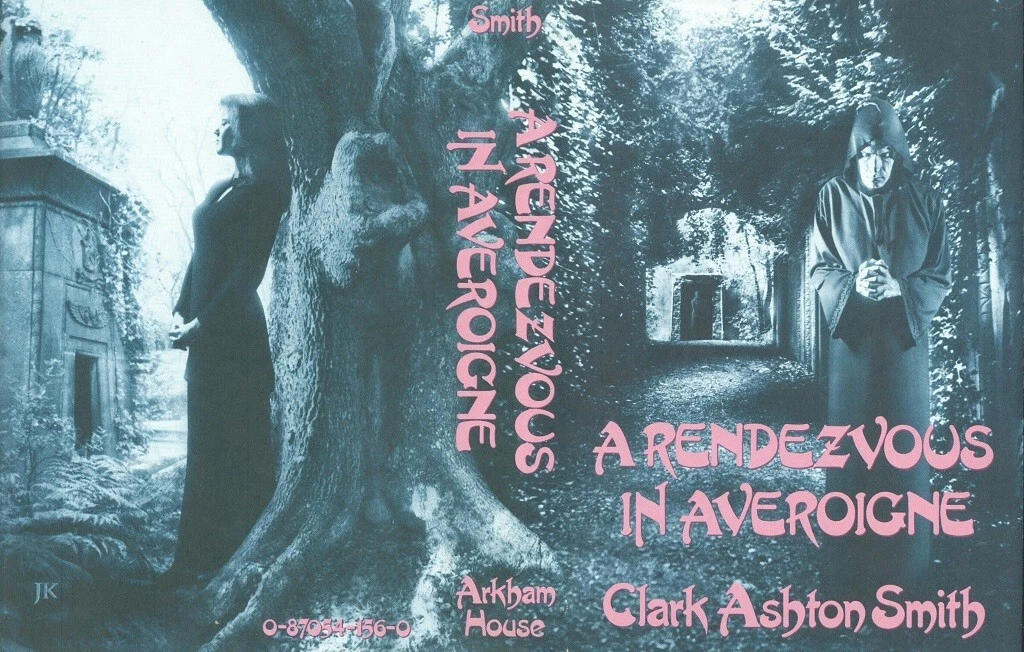

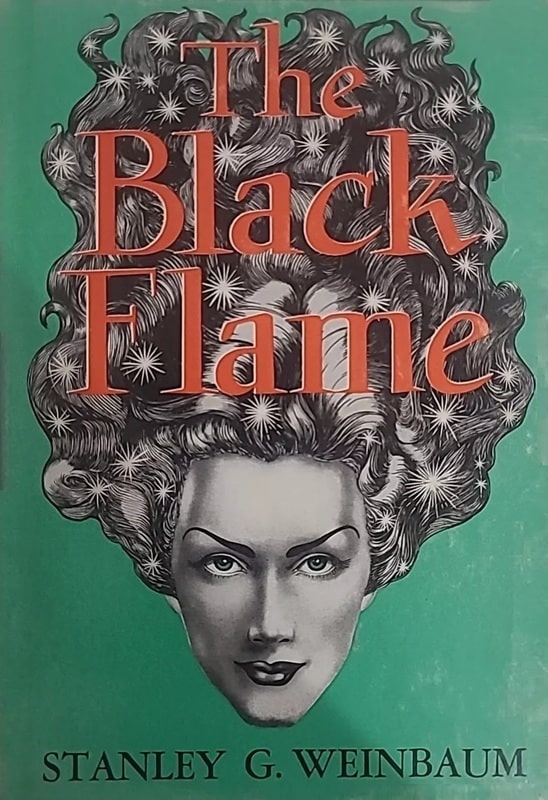

I heard about this. The book was The Black Flame by Stanley Weinbaum. Your father seems to have invented the standard method of dealing with plagiarists. You don’t accuse them outright, because you might get hit with a nuisance suit. You say “Because of similarities between your manuscript and The Black Flame we never want to see anything from you again,” and you send a carbon copy to everybody in the field, and you also keep the manuscript in case you have to prove it in court.

Exactly.

George Scithers told me about it. He may have been a recipient of one of those letters. It was a completely insane thing for the plagiarist to do, because of all the editors in the field, the one with the greatest depth of knowledge, who would be most likely to recognize a Stanley Weinbaum novel, would have been either Fred Pohl or your father.

Yes.

|

|

The Black Flame by Stanley G. Weinbaum (Fantasy Press, 1948). Cover by A. J. Donnell

A newer editor might not have. There have been cases where plagiarized books have been published.

I am sure, because there are so many books.

I remember a particularly canny case where the plagiarist got away with it. He didn’t take an old classic that fans love, like the Weinbaum. He took a Gardner F. Fox novel and under two different bylines sold it to two different publishers, both of whom published it. Because it was a completely mediocre Gardner Fox novel that no one had ever paid attention to, it got into print, twice. Of course this was discovered afterwards, but meanwhile the guy had taken the money and skipped.

One has to wonder why those editors published a mediocre novel to begin with.

It was sold to marginal publishers who maybe couldn’t get anything better. It was a professionally competent mediocre novel. Why was it published for the first time? Gardner Fox was not a great writer, but he got published steadily.

Probably because there were fewer books being written.

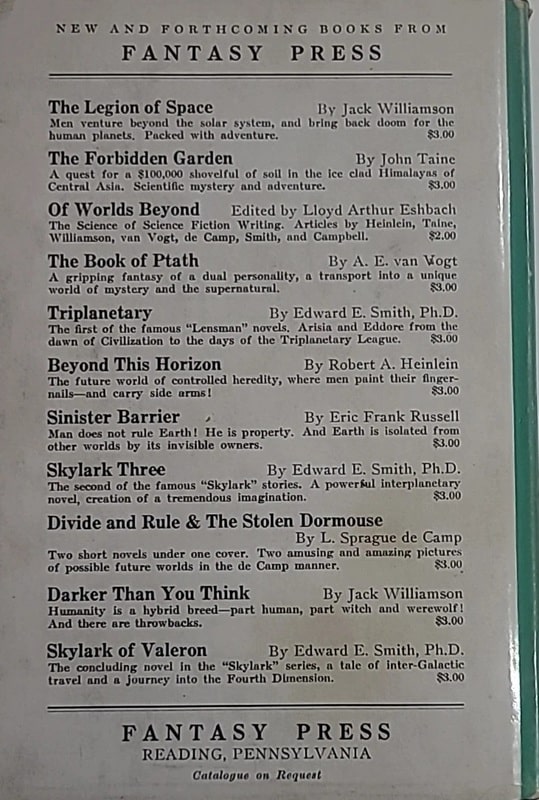

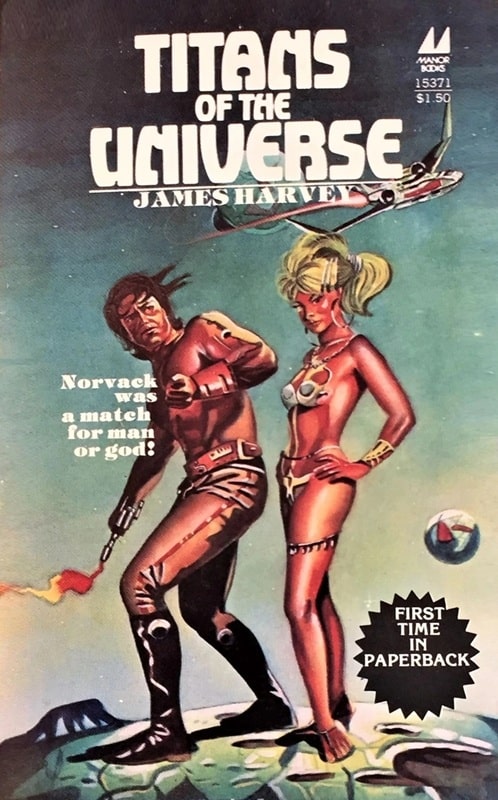

|

|

|

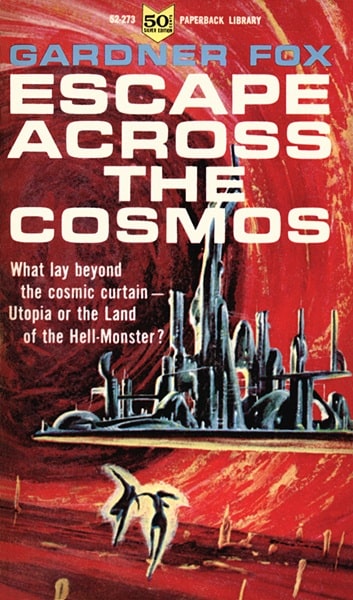

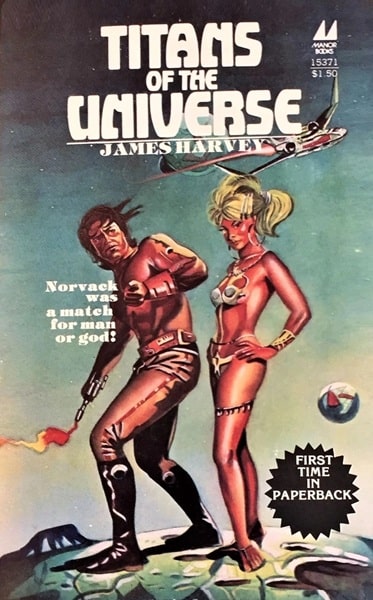

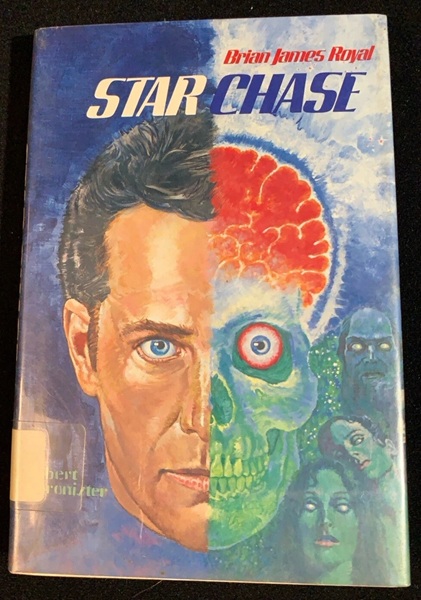

Escape Across the Cosmos by Gardner Fox (Paperback Library, March 1964) and two unauthorized

versions of the same novel: Titans of the Universe by James Harvey (Manor Books, 1978), and Star Chase

by Brian James Royal (Nelson Books, October 1979). Covers by John Schoenherr, unknown, and unknown

Elektra Hammond: You mean like Kothar and Kyrik, and all that?

Yes, that Gardner Fox.

Elektra: I had all of those. When you’re fourteen, those are great.

It was Escape Across the Cosmos, a space opera of some sort. I recall that one of the publishers who fell for it was a reputable hardcover house, Thomas Nelson. I was in SFWA already when I heard about this, so it must have been late ‘70s. The guy was basically a scammer. He wasn’t trying to have a career. He scammed two publishers and disappeared. He didn’t wait around for applause. So, as plagiarists go, he was a lot more clever than most.

Betsy Wollheim: Maybe with the future of AI, the AI could improve it.

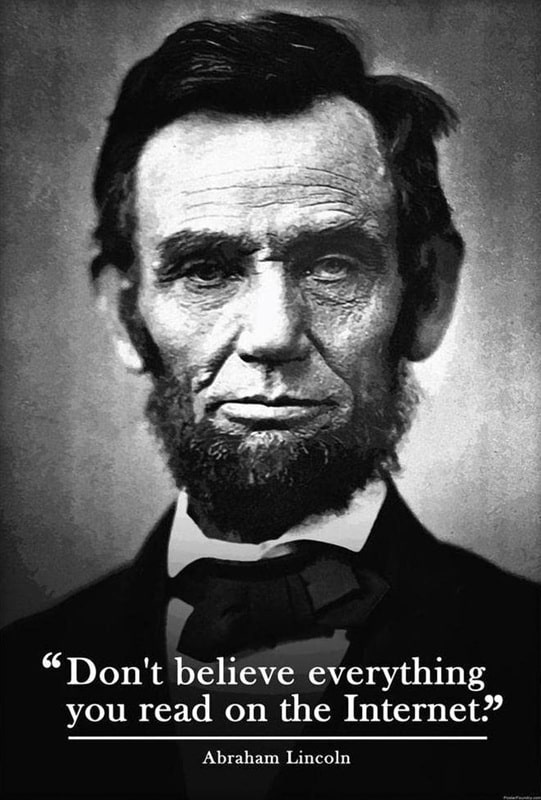

|

|

Titans of the Universe by “James Harvey” (Manor Books, 1978). Cover uncredited

It still won’t have any personality.

Betsy Wollheim: Eventually AI will have personality, because it will be stealing personality from humans.

Elektra: Kids under a certain age seem to think that anything on the Internet is free and they can just copy it and sell it or whatever. They have stolen my computer codes. I’ve had IP lawyers try to explain to them that this is not so. College kids…

Betsy Wollheim: The world is definitely getting stupider. Certainly less educated. I blame the Internet. I do. I blame social media. I love the Internet. Really. It helps me. But I always check my sources.

This is why I am very fond of that meme that shows a picture of Abraham Lincoln and it says “Don’t believe everything you read on the Internet. – Abraham Lincoln.”

From the meeting host [Hector Cruz]: I just want to thank Betsy for what she has done with DAW Books. They publish so many writers I love to read. Thank you.

[He thanks her for publishing LGBTQ authors and quotes the DAW mission statement from their website.]

DAW Books seeks to publish a wide range of voices and stories, because we believe that it is the duty of the science fiction and fantasy genres to be inclusive and representative of as many diverse viewpoints as possible.

Science fiction and fantasy have always been genres in which creators have infinite space to explore bold and inventive new ideas, while also reflecting the multiplicity of cultures, traditions, and identities of our own world. At DAW, we are proud of the work that our authors have already done to explore and celebrate diversity. We have a history of publishing feminist and LGBTQIA+ fiction, but we are always seeking to expand our own horizons, as well as those of our readers.

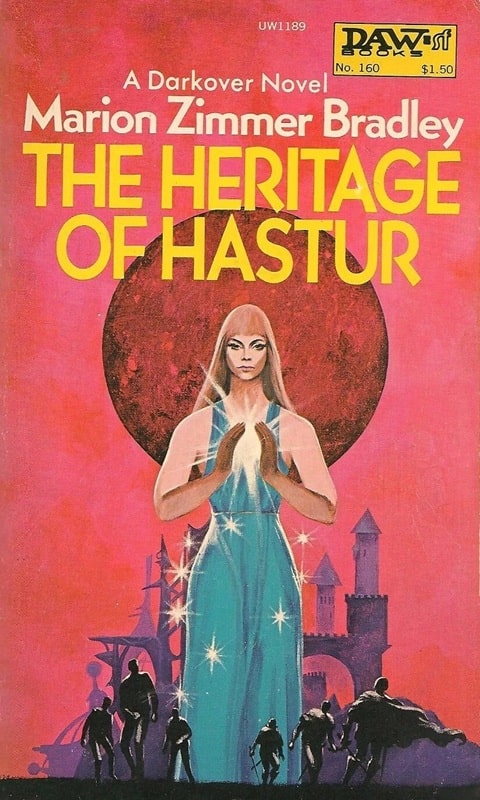

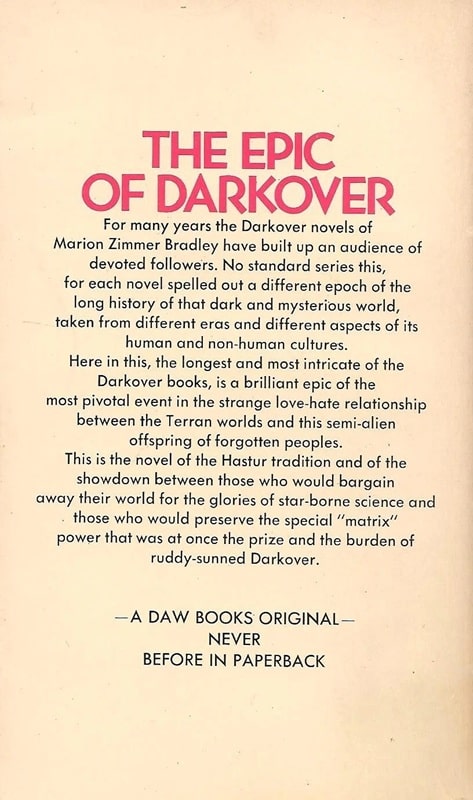

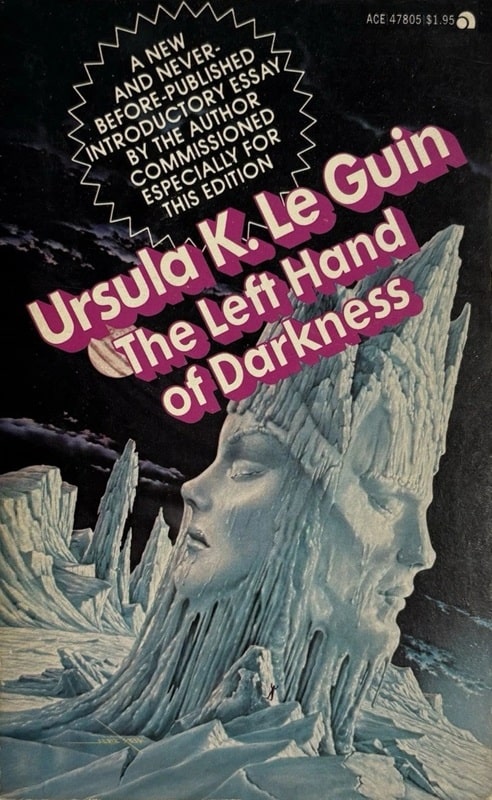

|

|

The Heritage of Hastur by Marion Zimmer Bradley (DAW Books, August 1975). Cover by Jack Gaughan

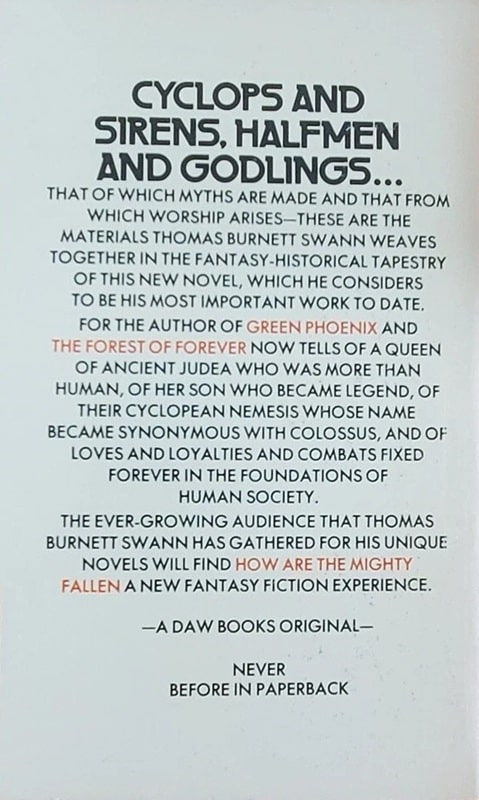

Betsy Wollheim: Thank you. Honestly, DAW has always been open to LBGTQ publications. In fact for a long, long time we felt that we had published the first book with a gay fantasy hero, and I still believe that to be true.

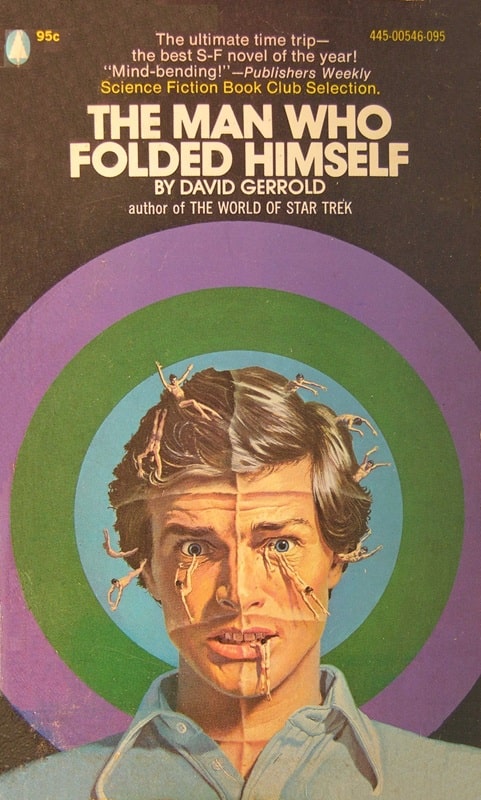

The Heritage of Hastur (nominated for the Nebula and Hugo Awards) by Marion Zimmer Bradley had a gay hero, and was published in 1975, but David Gerrold had published a science fiction novella about a gay man in 1973 two years before. So David Gerrold takes the award for being the first person to write about a gay main character in science fiction, and he won the Nebula for that novella, The Man Who Folded Himself.

|

|

The Man Who Folded Himself by David Gerrold (Popular Library, 1974). Cover artist unknown

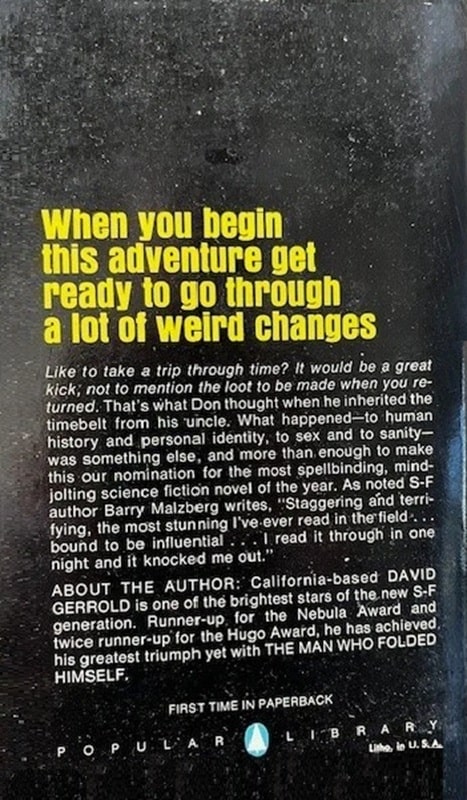

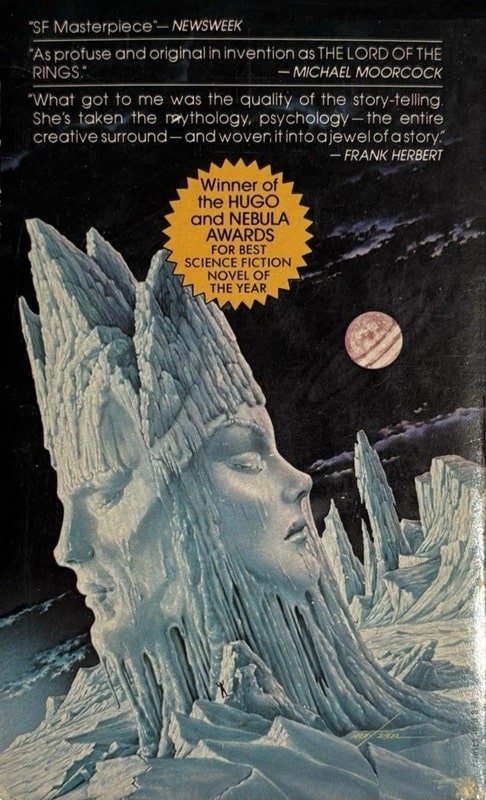

Marion followed him, in fantasy. But Marion felt enabled to write a gay hero by The Left Hand of Darkness. So The Left Hand of Darkness really opened that door. Ursula wrote about hermaphroditic aliens, who could change sex according to circumstance. So Ursula enabled Marion to feel that she could write The Heritage of Hastur with a gay male protagonist.

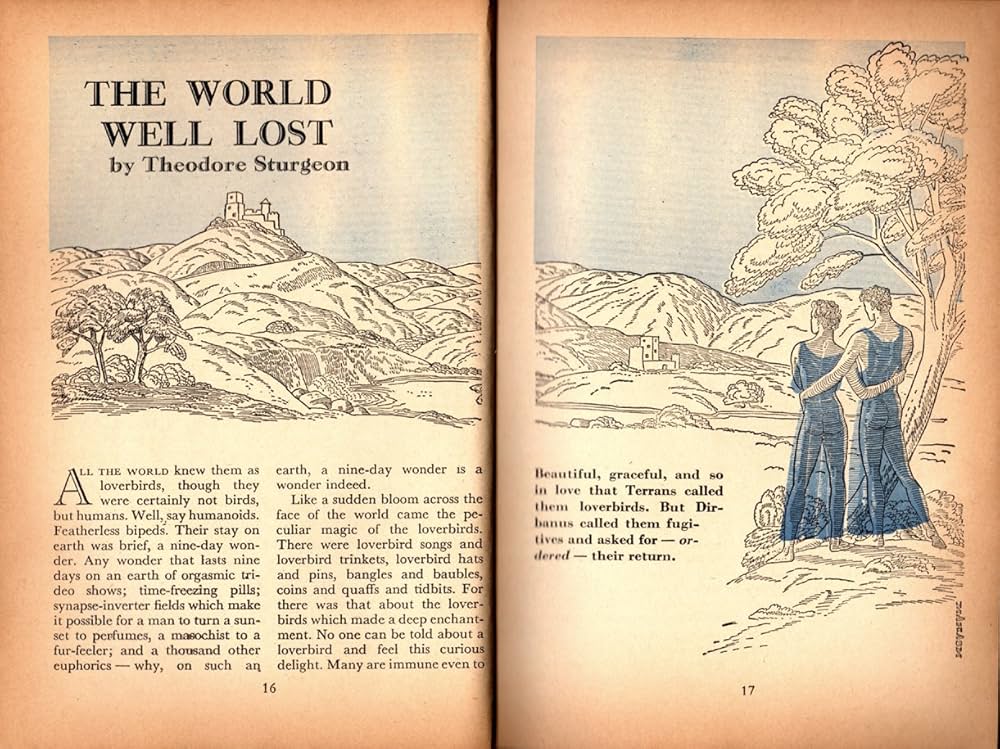

The first person to broach the subject at all, was Ted Sturgeon, in a story called “The World Well Lost.” It caused a great furor when it was published, in 1953, in one of Ray Palmer’s magazines. The big publishers wouldn’t touch it. Two humanoid aliens arrive on Earth. It is obvious that they are male lovers. They are fugitives from where they came from.

|

|

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin (Ace Books, November 1974). Cover by Alex Ebel

In 1953, I can see why no one would publish it.

The alien government demands them back, saying they are criminals and perverts, etc. In the course of the plot, both of them are killed. The Earth government has to inform the aliens that the two are dead. The aliens radio back, “You may now eat the bodies.” In the alien society, cannibalism was okay, but homosexuality was not. This was the first time the topic was ever touched upon in science fiction. The story goes that some editors didn’t want to deal with Sturgeon after that, but Ray Palmer was the craziest editor in the field at that time, so he would do stuff like that.

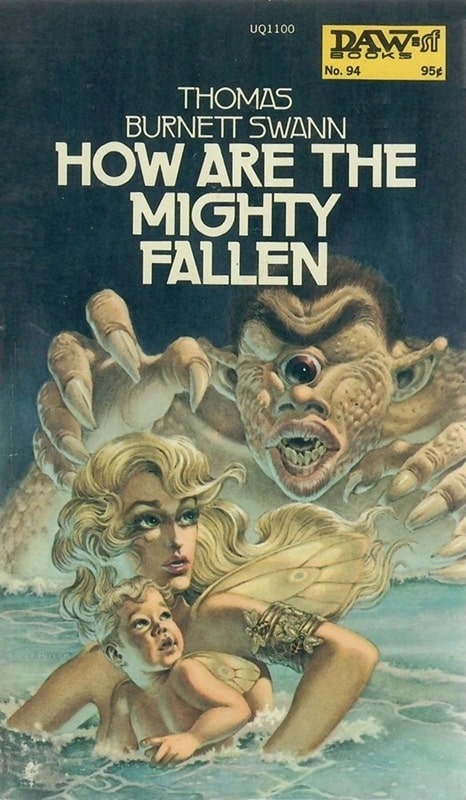

My father published a book by Thomas Burnett Swann. New American Library objected to the gay content of that book and tried to get my father to pull it, and my father refused. When my father stood firm, nobody could move him, so he published the book. [The book in question is How Are The Mighty Fallen, about the Biblical David and Jonathan, published by DAW in 1974. –DS]

He published a lot of Thomas Burnett Swann.

He did. He published a lot of gay authors.

|

|

How Are The Mighty Fallen by Thomas Burnett Swann (DAW Books, March 1974). Cover by George Barr

There was a time when Thomas Burnett Swann and Fritz Leiber were about the only fantasy writers around. Swann was even a Hugo finalist, twice, which was very rare for a fantasy writer.

There is a reason my father was partial to gay and alternative sexuality and gender culture. He was part of the very first ever trans woman’s group in America. There was a film made about this group recently. I was in it. I was one of the four people that knew some of the people involved. The group originated in the ‘50s and early ‘60s. The movie about that group is called Casa Susanna. It is on PBS, documentaries on demand. It was a very early group of mostly white, intellectual, well-educated, cultured men, most of whom were transgendered, but they all liked to dress in women’s clothing. They called themselves transvestites, because it was very early in the 1950s and 1960s and that’s the name they chose for themselves. Yeah, he was very partial to those people and many of our friends were transgendered, lesbian, gay people when I was a kid.

Miriam Siedel: Betsy, thank you so much for sharing your experiences, thoughts, stories.

Any time. I am very partial to the Philadelphia fan group because of my connection from the ‘60s.

Darrell’s last article for Black Gate was Part I of Daughter of DAW: An Interview with Publisher Betsy Wollheim.

I love Betsy. I love a lot of the books she’s worked on. I love DAW. But I hate that DAW puts no pressure on Pat who literally took a ton of money from us years ago from charity and refuse communicate, appologize, give us the Chapter we paid for, or refund us.

I personally stopped reading all DAW. Still have my DAW books, I’m not burning them or anything, but I’m not buying new ones. DAW has him under contract. There is no way they couldn’t get him to push out the chapter.

People like Betsy Wollheim, Robert Silverberg, Samuel Delany should be extensively interviewed so that much of the early history of Science Fiction and Fantasy does not get lost to the ages. I’m sure I am missing a number of other authors who have been around for decades; they should also be included.

I LOVED DON. PERSONALLY I BELIEVE THAT HE HAD A GREATER, BETTER AND MORE BENIGN INFLUENCE THAN CAMPBELL WHO WAS NARROW AND NOT VERY SMART. IF I HAD THE INFLLUENCE WE’D HAVE A WOLLHEIM AWARD NOT A JWC. I HAVE SPOKEN MANY TIMES OF DON AND TO A LESSER DEGREE LARRY SHAW AS EDITORS OF ENORMOUS INFLUENCE AND INTELLIGENCE. I FOUND THE INTERVIEW VERY AMERICANCENTRIC AND A LITTLE MORE FOCUSSED ON GENRE THAN DON MIGHT HAVE BEEN. ON THE SUBJECT OF GENDER, FOR INSTANCE. DON WAS A WIDELY READ MAN AND A HUGE INFLUENCE ON ME — STILL REMAINS MY HERO I ONLY ARGUED WITH HIM OVER NORMAN BUT CONTINUED TO LOVE DON AND ELSIE. I DON’T, I FEAR, KEEP UP WITH CURRENT GENRE, DON’TKNOW BETSY VERY WELL. DON WAS ADMIRED INN THE UK AAND HIS VISITS ALWAYS WELCOME. A GREAT MAN WITH GREAT TASTE . POLITICALLY WE GOT ON WELL BUT WE BOTH GOT ON WELL WITH RIGHT-WINGERS OF TALENT SUCH AS LEIGH BRACKETT. ED HAMILTON AND OTHERS. DON HAD FIRM POLITICAL IDEALS AND WE NEED A FEW MORE LIKE HIM NOW.

Between pt.1 and pt. 2 of this interview, there’s a really good explanation for the… hmm, “slightly dissatisfactory” condition of the science fiction and fantasy shelves in the book stores. One which I hadn’t even considered as a driving factor until now, but it makes total sense.

“Editorial super-saturation.”

Art students get so bombarded with figurative art through the ages that they ultimately start seeking and finding value in non-figurative, outsider, and even ugly art. Musicians end up so swamped with conventional chords and tonalities in various styles, that they end up longing for jazz chords and atonal music. And it seems that editors have to read so much of “what people want at the moment” that they end up seeking out and longing for that which is novel far sooner than some of us would want.

I wonder what the next development even now coming down the publishing pipeline will be.

Wonderful to hear from Ms. Wollheim.

Despite the contretemps and lawsuits, I still consider her father to be one of my Science Fiction heroes and one person who is largely responsible for establishing SF Fandom the way we used to know it: at some point in the 1930s, when Gernsback was promoting the Science Fiction League, Donald said (paraphrasing) “Fandom is not meant to serve commercial interests” and went about greatly discouraging the formation and continuation of SFL clubs.

It was very interesting to hear Ms. Wollheim offer up her take on Donald and Hugo.

It may have been Gernsdback who got the fannish ball rolling in the letter columns of Amazing and Wonder Stories, but it was Donald Wollheim and his Futurian compatriots who would go on to influence both fandom and science fiction publishing more than anyone else in the field.