Pseudoplumes, Nom de Nyms, Birds, & Oooze: Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Language of the Night

|

|

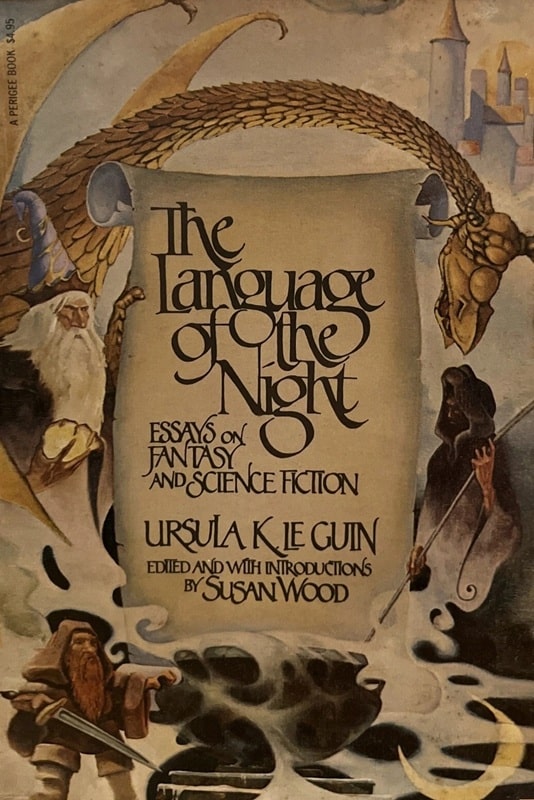

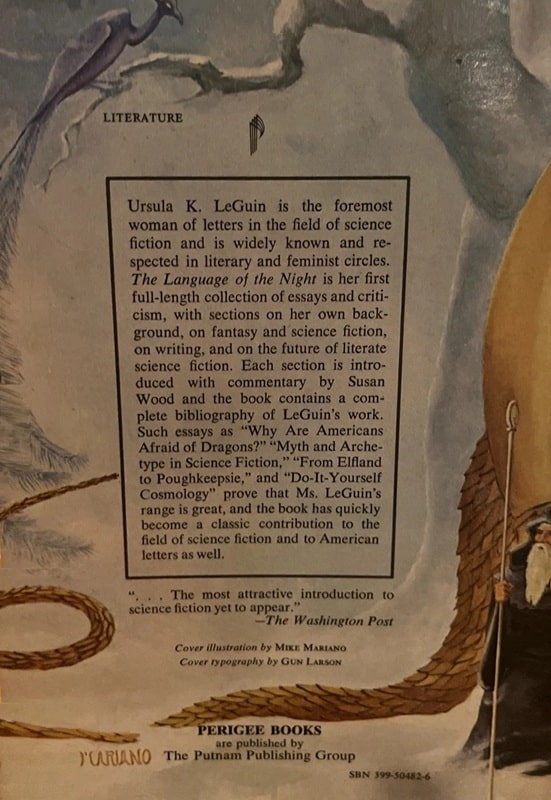

The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin

(trade paperback reprint from Perigee Books, 1980). Cover by Michael Mariano

I’m not a big fan of literary criticism in any field (although I have committed some), but one of my big books from my late teens onward was Le Guin’s The Language of the Night (1979), especially for the essays “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie” and “A Citizen of Mondath.”

Le Guin has some great passages in “Citizen” about what she liked to read as a kid, and how she liked it.

[Click the images for night-sized versions.]

|

|

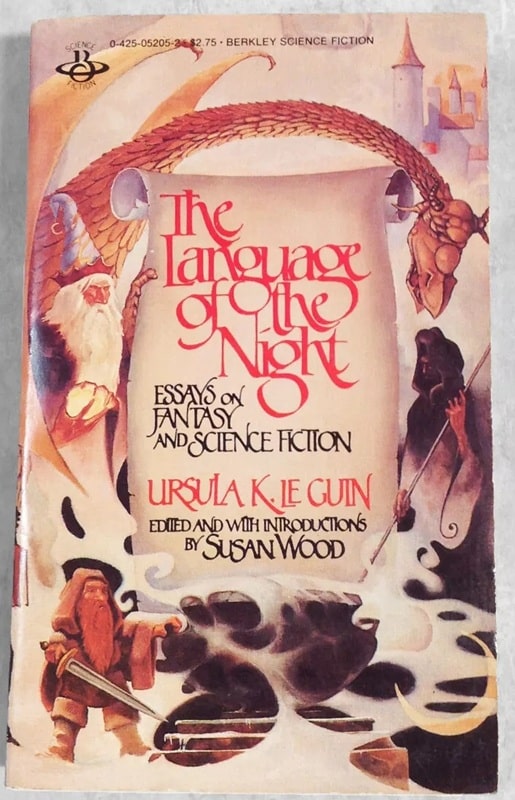

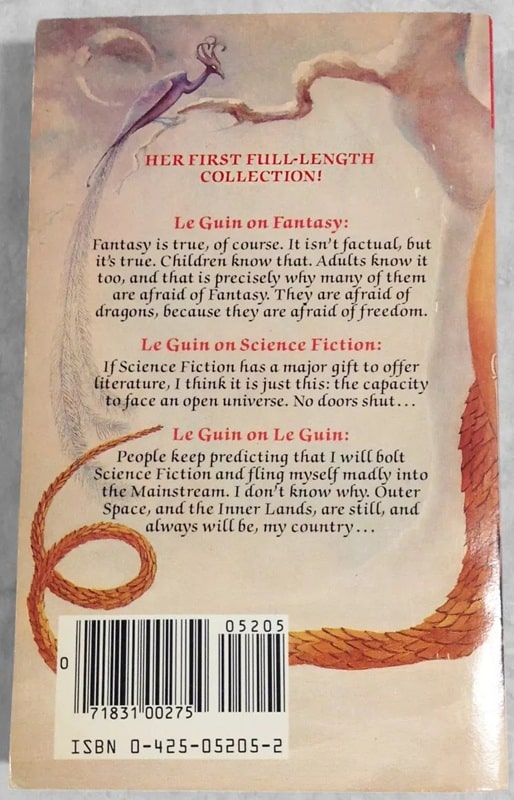

The Language of the Night (Berkley Books, January 1982). Cover by Michael Mariano

We kids read science fiction in the early forties: Thrilling Wonder, and Astounding in that giant format it had for a while, and so on. I liked “Lewis Padgett” best, and looked for his stories, but we looked for the trashiest magazines, mostly, because we liked trash. I recall one story that began “In the beginning was the Bird.” We really dug that bird. And the closing line from another (or the same?)—“Back to the saurian ooze from whence it sprung!” Karl made that into a useful chant: The saurian ooze from which it sprung / Unwept, unhonor’d, and unsung.

I wonder how many hack writers who think they are writing down to “naive kids” and “teenagers” realize the kind of pleasure they sometimes give their readers. If they did, they would sink back into the saurian ooze from whence they sprung.

I’m pretty sure the first story she refers to is “The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag” by Heinlein in Unknown (Oct 1942). It appeared under the false whiskers of “John Riverside” because at the time the Heinlein byline was reserved by John W. Campbell for RAH’s “Future History” stories.

The image by Kramer seems to depict a bird attacking a painting of a guy with a hooded skeleton behind him, but it’s kind of hard to tell from the blurriness of the scan.

I never figured I’d find the source of the mysterious “saurian ooze” – except that maybe I just did. In looking for Henry Kuttner stories online I found this opus in Strange Tales (Aug, 1939). The appearance is pseudonymous, because he had a “Prince Raynor” novelette in the issue under his own name. And the crucial phrase was from the editorial blurb rather than the story itself.

Kuttner, of course, was roughly half of “Lewis Padgett,” along with C.L. Moore. And most of their work, whatever name it appeared under, seems to have been collaborative from the time they met and married, so Moore may have exuded some of that saurian ooze herself.

Le Guin’s accounts don’t exactly match up with these texts: “In the Beginning was the Bird” is a ritual phrase used by the Sons of the Bird in Heinlein’s story (one of his best fantasies, by the way), but it’s not the opener of the story. And the saurian ooze springs out at the reader at the Kuttner story’s beginning, not its end (and with a shift of ablaut at that). But given that Le Guin was writing about these stories 20-30 years after she’d read them, I’d say the shoes fit the footnotes pretty well.

James Enge’s last article for us was a review of Dilvish, the Damned by Roger Zelazny. He lives in northwest Ohio, where he teaches Latin and mythology at a medium-sized public university. His first short story, “Turn Up This Crooked Way,” appeared in Black Gate 9 in 2005, and he was one of the founders of the Black Gate blog in 2009. His first novel, Blood of Ambrose, was nominated for the World Fantasy Award, and the French translation was shortlisted for the Prix Imaginales. He has a stories slated to appear later this year in New Edge Sword and Sorcery. You can find him online on Bluesky (@jamesenge). For traditionalists, he also has a website: jamesenge.com, where this article originally appeared.

And now I’ll be carrying saurian ooze around in my head forever.

I wonder if anyone else remembers an issue of Asimov’s in which three short stories by different authors all included the phrase “bubbling obscenely,” describing different things. If I had imagined when I read it that I’d still think of it from time to time for the rest of my life, I’d have kept that issue. Was the repetition a practical joke by the editors? At the expense of the editors? The one thing it cannot have been was coincidence. It took 35 years or thereabouts, but the phrase did eventually find a place in one of my short stories.

Getting from Poughkeepsie to Elfland is easier and more sublime than Le Guin ever guessed, if you know which spots in Poughkeepsie to look in.

“Getting from Poughkeepsie to Elfland is easier and more sublime than Le Guin ever guessed, if you know which spots in Poughkeepsie to look in.”

I’ve never been, but I wouldn’t be surprised. Dunsany puts the borders of Elfland within walking distance of “the fields we know” (in the intro to The King of Elfland’s Daughter, if I’m remembering right).

The real question is, did you ever pick your feet in Poughkeepsie?

On advice of counsel, I’ve decided to stand mute. Or, at most, say, “Eh.”

Wow, truly wish I had that copy of Asimov’s with the multiple “bubbling obscenely” phrasings. 35 years or so would be within my subscription time (1980 – 2006). But I cannot recall such a wondrous issue.

As for guides to Poughkeepsie, I am guessing that Ms. Le Guin would certainly pass on it. The closest she might come is pointing to Harlan as the guide to Schenectady, which she mentioned as his answer (being also the best) to the question of “Where do you get your ideas from?” (“Introduction to Planet of Exile”).

“A Citizen of Mondath” was my introduction to Lord Dunsany, and it compelled me to make an inter-library loan request for A Dreamer’s Tales. “Idle Days on the Yann” may be my single favorite fantasy short story. Thank you, Ms. Le Guin, for the recommendation!