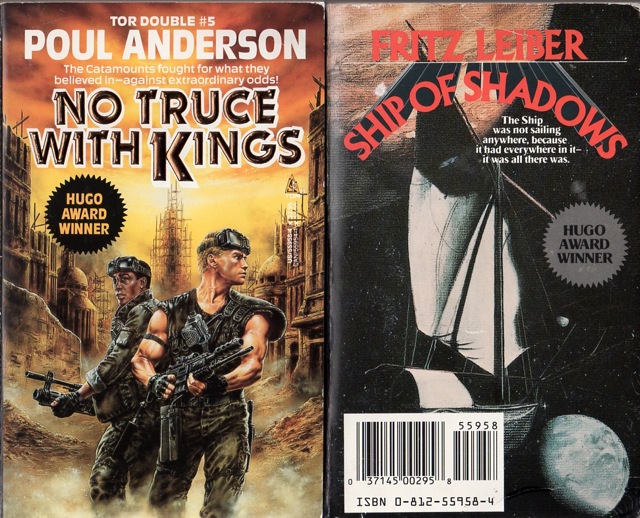

Tor Doubles #5: Poul Anderson’s No Truce with Kings and Fritz Leiber’s Ship of Shadows

Cover for Ship of Shadows by Robin Wood

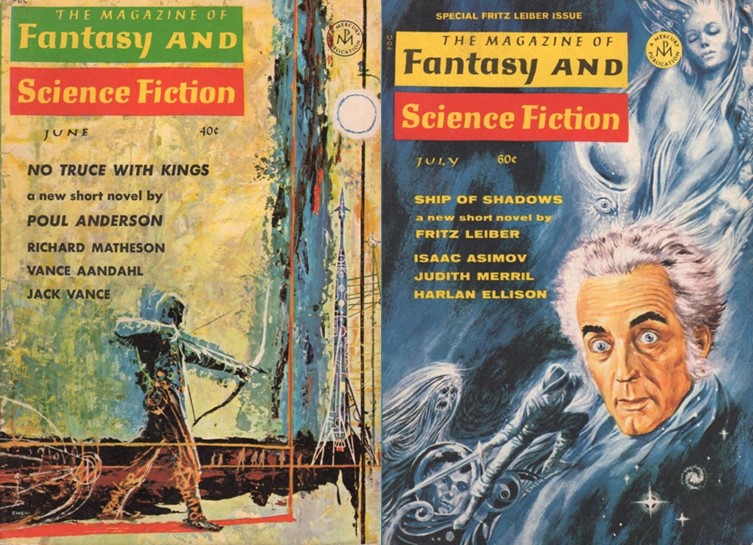

Both Poul Anderson’s No Truce for Kings and Fritz Leiber’s Ship of Shadows originally appeared in issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Not only did their initial publication occur in the same periodical, but both of those original issues sported covers painted by Ed Emshwiller.

No Truce for Kings was originally published in F&SF in June, 1963. It won the Hugo Award and received a Prometheus Hall of Fame Award in 2010. No Truce for Kings In is the first of three Anderson stories to be published in the Tor Doubles series.

Colonel James Mackenzie is the commander of Fort Nakamura in a post-apocalyptic California who receives a message that Judge Brodsky has been deposed and replaced by Judge Fallon. This message is the indication to Mackenzie that a civil war has broken out. Although Mackenzie and his troops are loyal to the old regime, the letter makes it clear that Mackenzie’s son-in-law, Thomas Danielis, is aligned with the rebels, as well as serving as a hostage for the troops who are coming to relieve Mackenzie of his command.

The story alternates between Mackenzie’s and Danielis’ actions in the subsequent war, and although Anderson includes many indicators of what the old regime looked like, with a series of local feudal lords called bossmen, and the attempts to destroy that society by the forces of Fallon and his allies, the use of time jumps throughout the story give it a somewhat disjointed feel. However, the use of a Mackenzie and Danielis, as relatives, along with the occasional appearance and frequent mention of Laura, Mackenzie’s daughter and Danielis’ wife, as well as her pregnancy and the birth of her child, combine to give the discussions of tactics and strategies a more personal flavor throughout the story.

While No Truce for Kings starts out as a pretty generic post-apocalyptic story, Anderson adds in an alien element that sets it apart. His aliens, who mostly appear in conversation with themselves as observers of the actions of the humans seem as if they are a response to the psychohistorians of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, which was originally published twelve years before No Truce for Kings. These aliens make use of psychodynamicism to guide the events of the humans as they come out of the fall of civilizations. Furthermore, while Asimov created the religion of scientism to help guide the galaxy, Anderson’s aliens have introduced Espers, people who ostensibly have psychic abilities.

The interludes have only a minor direct impact on the action of the story, but they allow Anderson to provide the information the reader needs so the main characters can continue interacting with their world without providing a data dump and allows the reader to have additional background knowledge they don’t have. When Mackenzie comes into contact with a group of Espers, who are theoretically neutral in the war between Fallon and Brodsky, the information Anderson has provided in the discussion of his aliens provides more depth to the Espers’ actions that may seem odd to Mackenzie but can be explained away, except the reader has an understanding where he has gone wrong.

Anderson doesn’t just place Danielis and his father in law on opposite sides of the war, he provides them with a reason for being on those sides. Mackenzie grew up in the system of bossmen and thrived because of it. To him it was the natural order of things. Danielis was an orphan who had to work his way up through the system, eventually succeeding in a military career. He was helped along the way by the Espers, and although they were officially neutral, there is no point in the story that it doesn’t seem like common knowledge that they are supportive of Fallon’s rebellion.

Eventually, of course, the existence of the aliens becomes known and changes the course of the war. The forces of Fallon and Brodsky, all of whom are aware that there was once a more unified country that had collapsed and all of whom have hopes to reestablish in their own ways, suddenly become aware that there is more out there, and can offer them a higher level of technology than humans had previously had access to. This is an area that Anderson had previously explored in works like The High Crusade, published three years before No Truce for Kings. Although Anderson addresses the dichotomy of science, it is done in an almost cursory manner, providing the story with something of an anticlimax from that point of view.

At the same time, his decision to follow Danielis and Mackenzie throughout, focusing on their experiences and the stresses caused by the knowledge that they were on opposite sides of the civil war, imbues the story with a human connection that ultimately does come to a satisfying conclusion, even if the situation does not allow for a happy outcome for all who are involved.

Fantasy and Science Fiction 7/69 cover by Ed Emshwiller

Ship of Shadows was originally published in F&SF in July, 1969, which was an issue dedicated to Fritz Leiber and included a portrait of him by Ed Emshwiller on the cover. The issue included essays on Leiber by Judith Merril and Al Lewis as well as a reprint of Leiber’s recent poem “iix. ‘Out the frost-rimmed windows peer,…’” and this original novella. Ship of Shadows was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award, winning the former. Ship of Shadows is the first of four Leiber stories to be published in the Tor Doubles series, including two that would be published in the final official release of the series.

There is a saying that science fiction (and fantasy) stories have to teach the reader how to read the individual story. The readers must be taught which words should be taken literally and which can be understood metaphorically. Nothing about the story’s setting can be assumed and the reader should allow the author to explain where the story is taking place. Leiber is more than happy to keep the reader in the dark about the actual location in which Ship of Shadows takes place, only revealing the details slowly.

The reader’s entry into this world is Spar, an older man who works as a bartender at the Bat Rack, a dive which serves moonmist, a low grade alcohol. Spar is accompanied by Kim, a talking cat who seems to be his closest friend, although Spar also has a connection with his boss, Keeper, and several of the bar’s patrons, ranging from Doc to Crown to the various women who frequent the bar. Those relationships range from awkwardly cordial to almost adversarial.

Spar has bad teeth and can barely see. He prefers to stay in his menial job at the Bat Rack rather than explore the world around him, taking comfort in the known space, even though it is relatively clear to the reader that even those who seem to have affection for Spar do not respect him or see him as an equal. Even Kim appears to view Spar more as a means to an end.

The world he inhabits appears to be one in which witches and zombies move with impunity, a four day week is in place which includes days for work, idleness, play, and sleep. The world, referred to as Windrush, may also be a ship of some sort, although the characters are not fully aware of its nature. How much of Spar’s knowledge of his world is accurate, how much is legend, and how much is authorial misdirection only becomes partially clear as the novella continues.

Just as Spar seems to have a limited understanding of the world in which he lives, Leiber isn’t in any hurry to provide the reader with any details. It isn’t until he is sent on an errand by Keeper that the world begins to come into an sort of focus, perhaps reflective of the fact that during the errand Spar plans to make a stop to see Doc and have him provide Spar new teeth and new eyes. In his travels, Spar discovers a that Windrush has a variety of different neighborhoods which don’t quite mesh with the world he has pictured living and working in the Bat Rack.

His travels take him to the Bridge, a world of “irregularly pulsing rainbow surfaces, the closest of which sometimes seemed ranks of files of tiny lights going on and off—red, green, all colors. Aloft of everything was an endless velvet –black expanse very faintly blotched by churning, milky glintings.” This revelation, which will be recognized by readers, is strengthened by the fact that it is described through Spar’s imperfect eyesight, which further reinforces the idea that, through no fault of his own, Spar’s impressions of his world of unreliable.

Because of the amount of information Leiber keeps hidden from the reader (and his characters), Ship of Shadows is the sort of work that benefits from re-reading. The first pass lives the reader at a loss for much of the story, but once the explanations come late in the tale, they can illuminate the earlier action when read with the knowledge of what Leiber will eventually reveal.

The cover for No Truce for Kings was painted by Royo. The cover for Ship of Shadows was painted by Robin Wood.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Ok, this one is pretty good too! 🙂 (I do think “Ship of Shadows” is one of Leiber’s most underrated stories.)

The title “No Truce with Kings” comes from a poem by Rudyard Kipling (one of Anderson’s favorite sources for quotations!), ” written at the start of the Boer War, and warning against repressive government, personified as “the old King”: “Suffer not the old King here or overseas.” Obviously Kipling meant more than just a literal denunciation of kings (as the Boers were not a monarchy) and that makes the title apt for Anderson’s story, which also is not literally about a struggle against monarchy, but one against centralized authority of all kinds—which in Anderson’s story is what the aliens are trying to create, or re-create. (This is easily read as a “right wing” view, coming from Kipling and perhaps from Anderson, but James C. Scott expressed a similar skepticism in The Art of Not Being Governed and his other books.) I don’t think “The Old Issue” is one of Kipling’s better poems, but it has some warnings that are no less timely than a century or more ago. And in any case I think spotting the allusion in Anderson’s title helps illuminate the theme of his story.

I read this and enjoyed both stories, but I did get thrown for a loop on Leiber’s story. Leiber’s works are very uneven in quality. I loved Our Lady of Darkness but consider The Mouser Goes Below one of the worse things ever published. I don’t think Ship of Shadows is his best but it was an interesting read.

Well, “The Mouser Goes Below” is Leiber indulging his personal kinks, I believe. So, yeah, not quite a great story!