Life Lessons from David Cronenberg

Let me begin with two assertions, each of which is, in the immortal words of Vincent Vega, “a bold statement.” First: David Cronenberg is one of our greatest directors, and there is nothing he has done that isn’t worth seeing. Second: I am the dumbest, most suicidally foolhardy person you will ever meet. The first statement is arguable, ultimately a matter of opinion, but the second is not, because I can prove it. In fact, I can use the first proposition to establish the validity of the second one.

In case you’ve been living under a rock for the past fifty years, David Cronenberg is the Mutant King of body horror; in stomach-churning, Manson Family date movies like Rabid (an extremely icky form of vampirism), The Brood (nasty little “rage monsters” popping right out of poor Samantha Eggar), Scanners (you want exploding heads — you’ve got exploding heads), and Videodrome (I… I can’t even talk about it, and to this day, neither can James Woods) he set new standards in shockingly gross special effects and in the number of times he forced audience members to barf in their popcorn buckets or make panicked rushes to the restroom.

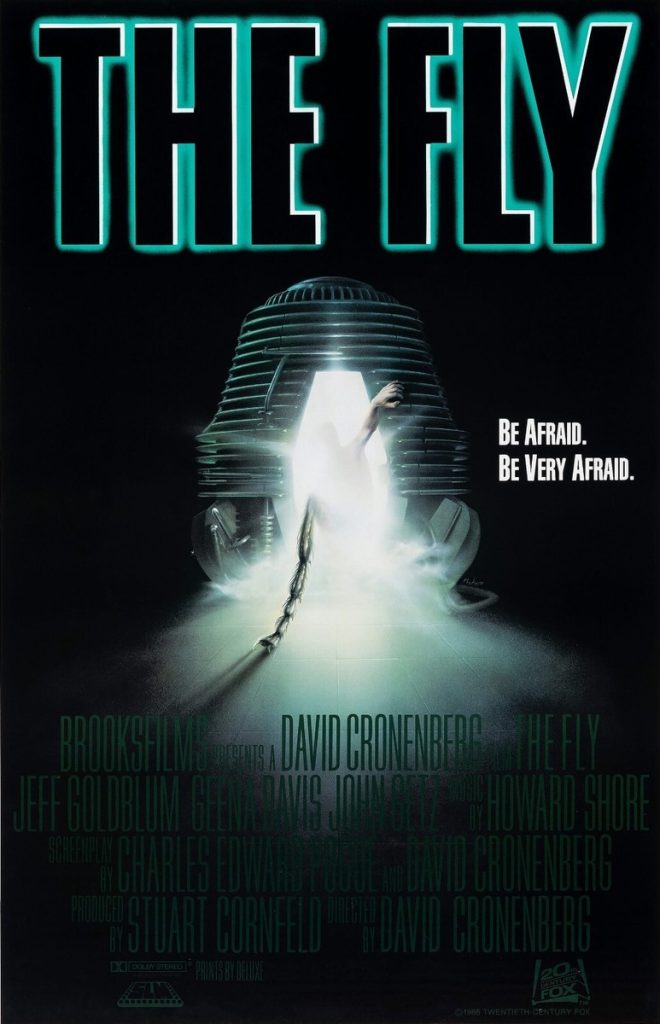

I thought all these movies were terrific (and not just because of the wild effects — wipe off all the blood and underneath you’ll find a sharp, mordant intelligence with something serious to say), so when Cronenberg’s version of The Fly hit the multiplexes in 1986 it was a must-see for me, and it was with high hopes that I took my lovely wife of barely eighteen months to see it. We were both looking forward to a fun night at the movies. Well…

I had a great time.

Marianne, on the other hand, checked out when Geena Davis gave birth to a bouncing baby maggot (which, to be fair, happened in a dream, so I don’t think it really counts) and spent the last twenty minutes of The Fly hunched over in her seat with her eyes tightly closed, waiting for me to give her the all clear, so she missed John Getz getting his hand dissolved into a bloody stump by fly-spit, Jeff Goldblum’s final insect form emerging while big chunks of his raw red flesh fell off and went splat on the floor, and the bug’s tragic end when his head gets blown to smithereens by a shotgun blast. (She assures me that hearing it all was just as nauseating as seeing it would have been.)

Hey, it was just one rocky evening at the movies; it could have happened to anyone. The main thing is to learn from an experience like that, right?

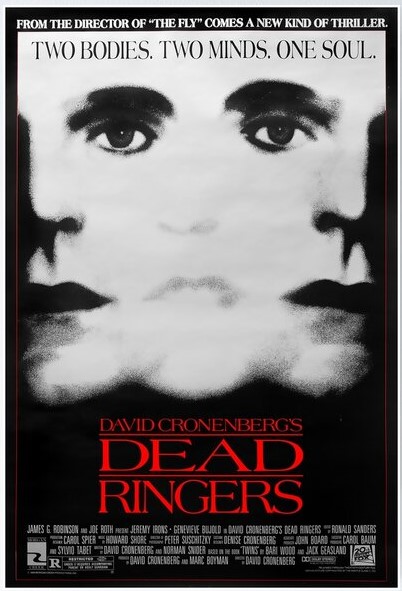

Fast-forward to 1988. Now the movie creating all the buzz isn’t The Fly — it’s a little something called Dead Ringers. Yeah, I know who directed it, but there are no exploding heads or weird vaginal apertures appearing where they have no business being in this movie. This one is a showcase for serious acting; it’s a character study, you know?

So it was that I persuaded my wife to go to another David Cronenberg movie. (I actually forgot to mention that he was the director. I guess it just slipped my mind.) Not only that, but I also convinced two of our closest friends to come along, women my wife taught school with. This will be great! Diane and Susan are going to love this movie, honey! It’s based on a true story! (Obviously, my motto is, “Be stupid. Be very stupid.”)

I wasn’t lying; Dead Ringers is a great movie, and it is indeed a brilliantly-acted character study. By any measure it’s a darkly seductive, ravishingly shot knockout.

So far, so good. There’s just one problem. Dead Ringers is also, first and foremost, a David Cronenberg movie. And there lies the rub.

Dead Ringers is about identical twin brothers, Elliot and Beverly Mantle, both played by Jeremy Irons. Elliot is smooth, socially ambitious, self-assured and confident (often too much so), while Beverly is introverted, cautious, and much more emotionally vulnerable than his glib twin.

The two characters share a lot of screen time, and one of the best things about the movie is how well Cronenberg employs all the tricks of the trade to make it seem as if Irons really is two different people in the same room together, a task made easier by Irons’ brilliance at subtly differentiating the brothers. (Whenever we see him alone, we instantly know which one he is.)

They are a peculiar pair, these two, and extremely close to each other, even for identical twins. They live together and are in business together, and often one brother seamlessly takes the other’s place when they have to appear at professional functions and the like, and no one is ever the wiser. (Remember The Patty Duke Show?) However, complications ensue when they start sharing the same lover, Claire Niveau, a movie actress played by Geneviève Bujold. The problem is that, for quite a while, Claire doesn’t know that she’s dealing with two separate people, and when she finds out, she’s not happy. Ooops.

The bulk of the movie is taken up with showing how first Beverly and then Elliot start to come apart under the pressure of their extraordinary personal and professional charade, with both brothers eventually becoming delusional drug addicts and descending into outright madness. As you might guess, it doesn’t end well, and things really go downhill when the fraternal craziness starts to manifest itself at the workplace; the whole ghastly situation is made far worse because of the unique nature of the twins’ profession.

What? I didn’t mention what the Mantle brothers do for a living? How careless of me.

No, they’re not architects. They don’t work at the DMV. They’re not certified public accountants or major league baseball players or long-haul truck drivers.

They’re gynecologists.

You begin to appreciate the depth of my folly, don’t you?

I began to think that I had made a mistake during the opening credits, which feature medieval woodcuts of women cross-sectioned to show the children they’re carrying against a background of antique medical instruments that look like they were found lying around Torquemada’s garage; the implications were not comforting.

My growing unease turned to outright panic when an increasingly demented Beverly uses a bulky surgical retractor to conduct an examination on an unfortunate woman; I don’t know if the lady was a method actress, but her winces and grimaces certainly seemed to be coming from someplace real. Halfway through this excruciating scene, I started looking around for an escape route, but I knew it was hopeless; they would drag me down before I made it halfway to the exit.

Then Beverly starts to believe that there’s “something wrong” with “the insides” of all of his patients, that all of the women he’s examining are actually mutants, and he commissions an avant-garde artist to make him a set of “gynecological instruments for working on mutant women.” They look like fruit hanging from a tree on some nightmare alien planet.

The twins operate a fertility clinic (judging from the body of his work — no pun intended — you have to believe that for Cronenberg, birth holds more horror than death), and when Beverly shows up for an operation with these grotesque instruments and actually tries to use them on a patient, he almost kills the woman and the career of the acclaimed Mantle brothers comes to an abrupt and ignominious end.

Despite my sense of impending personal doom, I was powerfully moved by the film’s somber ending, with the outcast brothers lying dead in each other’s arms, as close as they were in their mother’s womb, as close as they had always been during their tragic lives. It almost brought me to tears, in fact.

The tears on the faces of my wife and our friends, however, were of an altogether different kind. They say that it can get to almost fifty below zero in Antarctica. That’s positively balmy compared to the chill I felt walking out of the theater and in the car on the way home, and I was soon to learn that no lamed and bitter ex-cavalry officer can put as much rage and loathing into the word “stirrups” as your average woman can. Some things, I suppose, are just too personal for art.

Well, it was all a long time ago and all those fine ladies eventually forgave me for making them watch a gynecological horror movie, and I did learn a lesson. A year later, the shoe was on the other foot when I sat in the theater with the same group watching Steel Magnolias, and despite my agony, I knew better than to say a single word. I like having all my limbs.

Three or four years ago, I picked up a beautiful Criterion Collection edition of Cronenberg’s 1996 film of J.G. Ballard’s novel, Crash, which I missed when it was in the theater. When I read the book decades ago, my jaw hung open the whole time; it’s the most radically, shockingly transgressive thing I’ve ever read. Of course David Cronenberg made a movie of it. The Blu-ray has been sitting on the shelf since I bought it; I’ve never yet been able to work up the courage to actually watch it. Once seen, some things can never be unseen.

But I do wonder; some evening soon, Marianne is going to ask, “What are we going to watch tonight?”

What do you think? Should I…

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Odd Old Indie: Night Tide

Very fun read. 🙂

Alright. You have successfully verified your second statement. The Fly-transformation was particularly unsettling. Following it up with ob/gyn-twin horror was quite possibly your worst move, even after some years, and I’d wager that “stirrups” was only the second-most loathing-stuffed word for that evening, falling rather behind “men.” …It’s probably a good thing that “Patch Adams” was still some years away and couldn’t be a slant-thematic double feature.

Your approach to “Crash” is my approach to “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” I’ve been playing chicken with that DVD for a decade, now, and so far I’ve always been the one to flinch. “Will today be the day the cellophane comes off?”

Now that’s interesting. Cuckoo’s Nest is a movie I saw with my parents. It’s an emotionally draining film for sure, but what is it about its reputation that makes you balk at watching it? No one’s head blows up in it, that’s for sure.

True, no-one’s head blows up, except possibly metaphorically. I think it’s a combination of the emotional drain, the elements of muckraking reportedly in the film, and the cultural bogeyman stature that Nurse Ratched has taken on keeping me away. There’s bare mention of the actual story when anyone talks about it, it’s just “that movie is exhausting,” “can you believe asylums used to be like that,” and “oh, Nurse Ratched.” To my chagrin, I can usually get past two elements of dread when deciding whether or not to watch, but seemingly adding a third does me in. 🐔