Only Disconnect: Ray Bradbury’s “The Murderer”

High on the list of unwritten books that I’d like to read is An Encyclopedia of Misconceptions. I am unswervingly committed to traditional paper books, but this is one that I would have to read electronically; a physical book would just be too damn big. Everyone would have a chapter — men, women, LBGTQ folks, atheists, evangelicals, millennials, seniors, Democrats, Republicans, police officers, bus drivers, food service workers, Fortune 500 CEO’s, any racial or sexual or religious or social or political or generational or economic group that you can name, in fact — everyone feels misunderstood. Everyone knows themselves to be quite different from what other people assume them to be.

Such wrong ideas can attach themselves to almost everything in our lives, even including the books that we read. For example, one widespread misconception holds that the main purpose of science fiction is to predict the future! This notion is most rigidly held by those who have almost no familiarity with any actual science fiction. Such people gleefully point out SF’s failure to predict the internet (even though… well, we’ll get to that), or they “prove” the shallowness or silliness of the entire genre with the help of tales from the yellowing pages of Amazing Stories, yarns that depict a 21st century where everyone enjoys lives of anti-gravity-belt enhanced leisure with every want met by humanoid robot laborers (which hasn’t quite happened, in case you haven’t noticed).

But of course H.G. Wells didn’t really think that we were going to be invaded by Martians or believe that it was possible to concoct a formula that would make us invisible, nor was he convinced that vivisection could make the family dog into something that was virtually human. His books were really comments on the present in the form of visions of the future, and the technologies he invented were tools that enabled him to bring his own society and its potentialities into sharper focus.

One way to define science fiction is to say that instead of being a bet-your-life-on-it prediction generator, it is a way of thinking about social change in a technological age, and we feel those stories lacking where technological change is imagined without a corresponding change in the society which produced it. (How quaint the old far future Gernsbackian stories now seem to us, the ones where vast machines have physically transformed the world but where the hero and heroine go out on a date and act like it’s still 1912.)

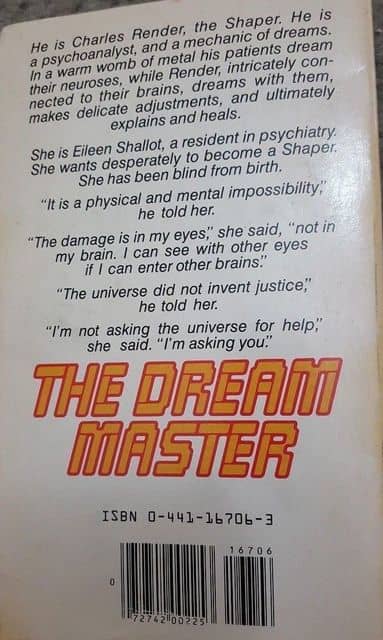

It’s not that hard to come up with plausible new technologies. Over the past few years, it’s become clear that we’re well on the way to self-driving cars, but those have been a staple of science fiction for a very long time. The harder part is imagining just what effects a particular technology will have on people’s lives, the ways that it will change how they live and who they are, especially because so many of those changes will be unforeseen and unintended. (In Roger Zelazny’s 1966 novel The Dream Master, the people of his future world are so bored and purposeless that they use their automated cars in a kind of game to stave off the deadly ennui that envelops them — they program the vehicles to take them to random destinations, over and over. His world is full of empty people traveling endlessly through the night, on trips to everywhere and nowhere. Well, we’ll see…)

|

|

Though producing uncannily accurate prophecy isn’t the main intention of most science fiction writers – too many things work against it – every now and then, in using invented technologies to speculate about change and its social effects, someone hits a bull’s eye.

A case in point: the internet — or at least, a technology that provides instantaneous (and often intrusive) information and advice — was predicted by Murray Leinster in his 1945 story “A Logic Named Joe.” And Leinster doesn’t just imagine the tool; he shows the disruptive effects such a technology has on the daily lives of those who use it. The technology itself isn’t the point of the story — the question of how you live with such a change is. Chalk one up for our side.

Murray Leinster

Leinster’s story is often cited, but there is another that can stand right alongside it and that in many ways goes even deeper — Ray Bradbury’s “The Murderer,” which first appeared in his 1953 collection, The Golden Apples of the Sun.

“The Murderer” is a more pointed variation on one of Bradbury’s most famous stories, 1951’s “The Pedestrian.” That’s the one, as I’m sure you remember, about mild-mannered Leonard Mead, who is arrested (by an autonomous police car) for the anti-social crime of strolling around his neighborhood on a cool evening, when all respectable citizens are in their houses staring at television screens.

As is often the case with the superficially sunny Bradbury, the message of “The Pedestrian” is a dark one: gentle individualism is helpless against the steamrolling forces of technological progress, at least for these five pages. Leonard Mead has no power, no voice; he talks to the robot police car but it doesn’t truly hear him. It can’t; it’s a machine, just as his dehumanized neighbors have made themselves little more than viewing machines, oblivious to real-world experience as they sit in their darkened television rooms “like the dead, the gray or multi-colored lights touching their faces, but never really touching them.”

“The Pedestrian” can be seen as a bit of an artifact, as just another example of the 50’s egghead’s disdain for the lowbrow boob tube. Bradbury’s main argument seems to be that television separates people, isolates them in their sealed houses, provides a druglike substitute for genuine human contact. It didn’t turn out as bad as all that, though, did it? And anyway, Bradbury did plenty of TV work himself during his career, so he must have realized that people were not as susceptible to cathode ray hypnosis as he had feared. And surely he would have felt differently about the actual future, the one we’re living in now, in which a technology of smart devices is continually connecting us all. For the answer to that, let’s consult “The Murderer.”

Young Bradbury

For the crime of walking, Leonard Mead was ultimately sent to the “Psychiatric Center for Research on Regressive Tendencies.” The protagonist of “The Murderer,” Albert Brock, finds himself delivered by the police to a similarly hellish place in the universe of Punitive Bureaucratic Altruism — Interview Chamber Nine in the Office of Mental Health.

Brock is there because he has started to destroy devices. He commits these “murders” to still the incessant chorus of voices which have come to dominate his every waking moment. The nameless psychiatrist who is attempting to help Brock begins the interview by asking, “Suppose you tell me when you first began to hate the telephone.” If this was not the most loaded question of 1953, it surely is today. After declaring that he’s disliked the instrument since childhood, Brock launches an extended rant that’s worth quoting at length, since it paints a nightmare world of ceaseless intrusion and interruption that by now should be all too familiar:

It’s easy to say the wrong thing on telephones; the telephone changes your meaning on you. First thing you know, you’ve made an enemy. Then, of course, the telephone’s such a convenient thing; it just sits there and demands you call someone who doesn’t want to be called. Friends were always calling, calling, calling me. Hell, I hadn’t any time of my own. When it wasn’t the telephone it was the television, the radio, the phonograph. When it wasn’t the television, the radio, or the phonograph it was motion pictures at the corner theater, motion pictures projected, with commercials on low-lying cumulus clouds. It doesn’t rain rain anymore, it rains soapsuds. When it wasn’t High-Fly Cloud advertisements, it was music by Mozzek in every restaurant; music and commercials on the busses I rode to work. When it wasn’t music, it was interoffice communications, and my horror chamber of a radio wrist watch on which my friends and my wife phoned every five minutes. What is it about such “conveniences” that makes them so temptingly convenient? The average man thinks, Here I am, time on my hands, and there on my wrist is a wrist telephone, so why not buzz old Joe up, eh? “Hello, hello!” I love my friends, my wife, humanity, very much, but when one minute my wife calls me to say, “Where are you now, dear?” and a friend calls and says, “Got the best off-color joke to tell you. Seems there was a guy — ” And a stranger calls and cries out, “This is the Find-Fax Poll. What gum are you chewing at this very instant?” Well!

Could it be put any better? Albert Brock finds himself so constantly connected to everyone else, whether he knows them or not, whether he wants to be in touch with them or not, whether the connection is actually important (or even minimally necessary) or not — that there’s no longer any room for him to exist as a separate person; he’s being crowded out of his own life. He finds himself living in an age of herd individualism in which technology and the social habits it fosters reveal themselves to be ever more hostile to the solitary experience that he constructs his identity out of. Albert Brock is being torn to pieces by the merciless demands of incessant connection; he has to kill in order to live.

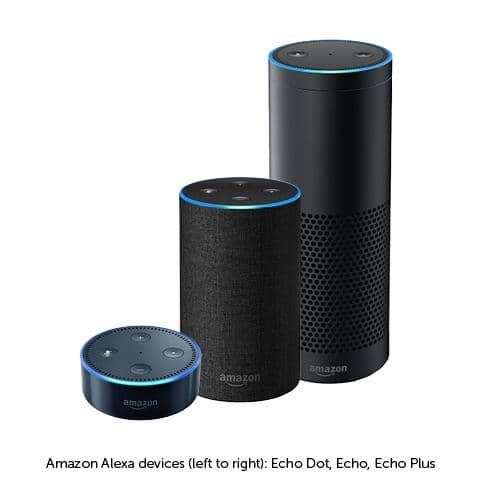

Our Robot Master

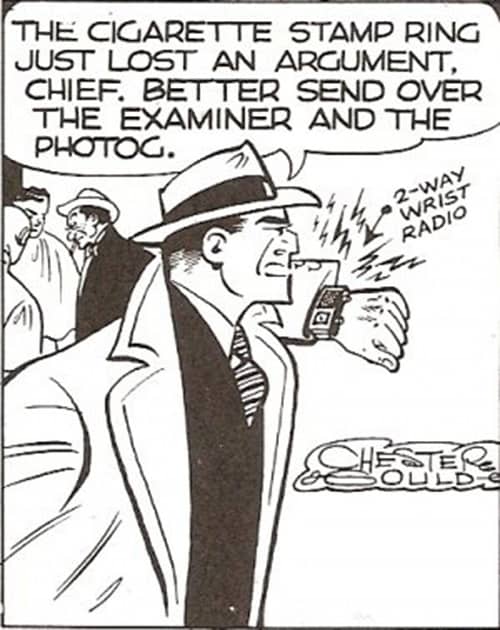

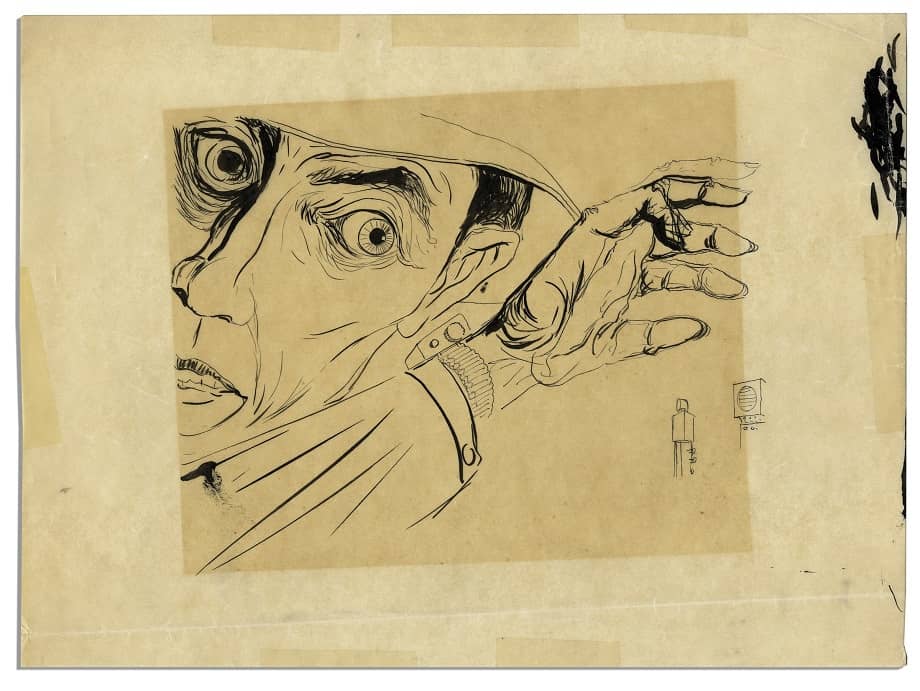

And so he sticks his home phone into the garbage disposal. (“I have nothing whatever against the Insinkerator; it was an innocent bystander.”) He empties a gun into his television screen. (If Bradbury had had any inkling of today’s landscape of reality shows, hour-long infomercials, and ideologically slanted “news” programs, he doubtless would have had Brock reload and pump in another six rounds.) He sabotages his office’s intercom system. He drops his wrist radio on the sidewalk and stomps it to death, silencing a poll-conducting voice that had just begun to blare out of it. (Need I say that Bradbury’s “wrist radio” is virtually identical to a smartphone? We’ve come a long way since the days of Dick Tracy — just contrast Chester Gould’s depiction of the device as the detective’s passive servant with Joe Mugnaini’s nightmare illustration of it from “The Murderer.”) He gives the quietus to his car radio by spooning French chocolate ice cream into the transmitter.

After using a “portable diathermy machine” to knock out all of the electronic intrusions on his bus ride home (“The bus inhabitants faced with having to converse with each other. Panic! Sheer, animal panic!”), Brock lays plans to murder his house, “one of those talking, singing, humming, weather-reporting, poetry-reading, novel-reciting, jingle-jangling, rockabye-crooning-when-you-go-to-bed houses. A house that screams opera to you in the shower and teaches you Spanish in your sleep.” A smart house — too smart, so he shoots his talking door and his hectoring, nagging stove and the robot vacuum cleaner that haunts his steps like a bad conscience and every other device in this domestic oasis of ease and convenience.

Bradburys Radio

Albert Brock is clearly crazy — crazy enough to ask the unspeakable question: “Convenient for who?” Convenient for his friends, convenient for his office, “so when I’m in the field with my radio car there’s no moment when I’m not in touch. In touch! There’s a slimy phrase. Touch, hell. Gripped! Pawed, rather.” Convenient for his wife, convenient for advertisers and poll-takers and salesmen and everyone, anyone but Albert Brock.

The psychiatrist isn’t persuaded by these admittedly somewhat excited explanations, and his patient looks to be in for a long, long stay. That’s fine with Albert. The unrepentant murderer is looking forward to the rest and the quiet, confident that he is but the first, “the vanguard of the small public which is tired of noise and being taken advantage of and pushed around and yelled at, every moment music, every moment in touch with some voice somewhere.” The motto of Howard’s End, E.M. Forster’s 1910 novel of the barriers that we erect against each other, is “only connect.” Albert Brock envisions a day when people will be fed up enough to disconnect, perhaps as a first, necessary step in reforging more genuine, more truly human links between each other.

“The Murderer” — a nutty story, a mere metaphor, a loony 1950’s fossil from one of those wild-eyed science fiction writers. Them and their jetpacks! What does any of it have to do with today’s problems, with where we find ourselves now? A yarn like this certainly can’t provide any insight into our own unique predicament, can it? You be the judge; listen to Albert Brock explain the situation to his incredulous doctor:

It was all so enchanting at first. The very idea of these things, the practical uses, was wonderful. They were almost toys, to be played with, but the people got too involved, went too far, and got wrapped up in a pattern of social behavior and couldn’t get out, couldn’t admit they were in, even. So they rationalized their nerves as something else. “Our modern age,” they said. “Conditions,” they said. “High-strung,” they said.

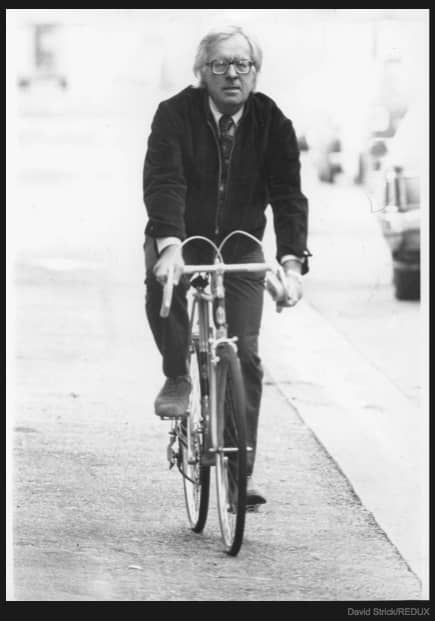

That, ladies and gentlemen of our Alexa, Siri, smartphone, social media age, is what they call a bull’s-eye. Can’t get out… can’t even admit that you’re in. Ray Bradbury was ahead of the pack in seeing that the kind of connective (and as the story implies and as many people are finding, positively addicting) technology that is pervasive in Albert Brock’s world — and now in ours — may paradoxically accomplish nothing more than amplifying our loneliness; he saw that a connectivity enabled, encouraged, mediated, and made virtually mandatory by technological means could become a curse instead of a blessing. No wonder Bradbury insisted on riding a bicycle.

Ray Riding

At the end of “The Murderer,” a smiling Albert Brock is left to his “madness” and his extended vacation. His uncomprehending psychiatrist leaves the interview room and goes on his own way “through the remainder of a cool, air-conditioned, and long afternoon; telephone, wrist-radio, intercom, telephone, wrist-radio, intercom, telephone, wrist-radio, intercom, telephone, wrist-radio, intercom, telephone, wrist-radio, intercom, telephone, wrist-radio… ”

And so, my friends, we can leave Ray Bradbury and his outlandish vision behind and can now return to the remainder of our day; Facebook, cellphone, Google, YouTube, Facebook, cellphone, Google, YouTube, Facebook, cellphone, Google, YouTube, Facebook, cellphone, Google, YouTube, Facebook, cellphone, Google, YouTube, Facebook, cellphone, Google…

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of a truly old-school fantasy: The Iliad.