The Real Tartan Tat Army! A review of Better is the Proud Plaid by Jenn Scott

What if I told you that the Highland army at Culloden in 1746 wasn’t really a “Highland” Army?

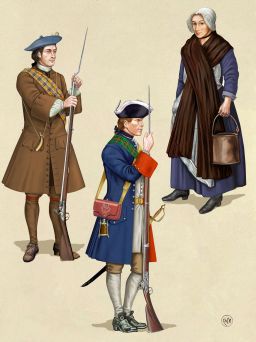

What if I also told you that apart from a few front-ranking testosterone-poisoned sword and targe men, it fought like any other 18th century European army and that at least half the men looked like regular soldiers draped in tartan tat — sashes, tartan trews, a better quality version of the kind of stuff tourists still pick up in Edinburgh’s gift shops — to show which side they were on?

Yes, I’ve been reading Jenn Scott’s new Better is the Proud Plaid: The Clothing, Weapons and Accoutrements of the Jacobites in the ’45. (UK, US)

It’s so far out of my normal period that I’m in danger of doing that thing where I age before your eyes and turn into a puddle of steaming goop.

However, every Scot grows up with the tale of Bonny Prince Charley, the ’45 Rebellion, and the tragic Battle of Culloden. Me being an Anglo-Scot, my ancestors, if involved, wore red coats and cursed in Nottinghamshire accents while they fought for Good King George. No wonder, then, that I’ve always been suspicious of the noble-savage-fighting-for-Scottish-freedom-while-swiving-time-travelling-American-nurses narrative that has wrapped itself around the rebellion. This book promised to debunk some of that — which it does, but in doing so replaces it with something perhaps more impressive.

And, also, I was expecting to be impressed. I’ve been hearing about Jenn’s research for years.

I’d love to say I met Jenn at some Edinburgh literary event, but actually she’s part of the local HEMA/Re-enactment continuum — I have a vague memory of a particularly good party when the world was young — and our subsequent historical discourse took place in the cafe of the kids’ weekend music school while the other parents dived for cover. Jenn is both an actual scholar — she gets papers published in military history journals — and a multi-period exponent of Living History, meaning she can tell you not just what? and how? and when?, but also why? and what the practicalities were, and — better yet — also provide citations. In other words, she’s not just making **** up, or passing on **** people told her, perennial a curse of the entire reenactment scene. Needless to say, Jenn’s my goto for medieval laundry practices, household organisation, costume, mores, culture and social structure.

And now she’s written this book for Helion’s From Reason to Revolution series, which is very like something Osprey might produce, but with a slightly fewer illustrations, and slightly more social history, making it a goldmine not just for authors, but for those recreating the era, whether on the tabletop or in the drizzle of Scotland’s outdoors. All those details make this an invaluable reference work. However, they are also evidence backing the main argument of what’s basically a monograph about the Jacobite army of the 45′.

This book is not a recounting of the campaign. Rather it covers the army’s material culture and logistics in a way that’s… illuminating.

It turns out that the Jacobite army stopped being primarily a Highland one after Prestonpans, when Lowland recruits made up about half the army… I say about, because even before that it included some regular Irish and one “Scottish” regiment from the French army (long story!). It picked up more recruits in England, plus deserters from the Government army, some of whom kept their uniforms long enough to be executed in them.

Of the half of the army that did look like Highlanders, many were merely adopting the look. Highland dress in general and tartan in particular had long been a way to signal Jacobite allegiance, so tartan was “on brand”. The other half of the army, the ones not flaunting their legs in kilts — yes, that was very much of a thing according to the Gaelic sources — wore at least some tartan along with the white cockade as a kind of uniform. This was especially important for those foreign soldiers whose uniform coats were red…

Talking of red, far from being in Braveheart earth tones that faded — romantically but tragically, with a hint of ripping bodices — into the landscape, the tartan was woven from wool coloured using modern (for the 18th century) dyes, especially — yes — bright red, whether the material was locally produced or bulk-ordered from a Lowland factory — ironically, the main supplier was based at Bannockburn!

Oh and while we’re on tartan: though particular patterns were used as regimental “liveries”, there was no such thing as a clan tartan… that was a later romanticising innovation. Also, contrary to modern myth, Scotsmen did wear something under their kilts! Like other European 18th-century men, they wore long shirts that fastened between the legs to make a kind of onesie. They were also fastidious about having a nice clean shirt.

The military equipment and doctrine wasn’t particularly Highland either. Though the original musters included men with Lochaber axes, improvised glaives, and targes — the distinctive round bullet proof shields — foreign supplies and looted equipment soon ensured that the army drilled and fought with modern muskets and pistols. That famous Highland charge was, for the most part, a bayonet charge. (Sorry.)

The picture that emerges is not a last gasp of the Old Ways Before They Faded into the Celtic Twilight (Pass My Classarch that I Might Sing A Lament). It’s something far more impressive: an 18th century army complete with heavy cavalry and artillery, conjured into existence with the help of foreign backers, supported by dashing logistical operations — smuggling and blockade running — and drawn from the whole of the north of the United Kingdom, not just Scotland, let along the Highlands.

This rebel force posed a serious threat of regime change, or worse, sustained civil war, which we did that in the 17th century and didn’t like it much. For me, that puts in context the brutal government response in the aftermath of the defeat. The final tragic irony is that, because the Jacobites had appropriated the Highland brand to their own, this brutal response was focused on dismantling the culture and society of the Highlands leaving the other rebel areas unaffected. The rest is history, modern history.

M Harold Page is the Scottish author of The Wreck of the Marissa (Book 1 of the Eternal Dome of the Unknowable Series), an old-school space adventure yarn about a retired mercenary-turned-archaeologist dealing with “local difficulties” as he pursues his quest across the galaxy. His other titles include Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”) and Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)

Very interesting, Harold. The cover illustration is particularly telling – a bunch of lads in highland colours, but carrying muskets!

Do you remember ‘Rob Roy’? It came out the same year as ‘Braveheart’ and is by the far the better film imo (Hurt and Roth are particularly good).

Ireland fared slightly better than Scotland, partially for geographical reasons (it was an island) partially – I reckon, although I’m open to correction – because the ruling classes didn’t suffer the same divided loyalties as the Scottish lairds, who tried to serve both the crown and their own (a loyalty which I’m guess was reciprocated by their respective clans): in Ireland, the ruling classes were mostly English blow-ins and distrusted by the people they ruled.

*Bright* Highland colours! And the chaps on the left – conventional costume plus a swatch of tartan. 🙂

Don’t know about the Irish. Paraphrasing the pre-schooler book: “That’s not my period, there’s not enough armour…p

No armour at all! (the middle ages pretty much passed us by)

> No armour at all! (the middle ages pretty much passed us by

You mean in Ireland? On the contrary, galloglasses were renoun for their iron shirts, and fabric armour seems pretty standard.

[…] History (Black Gate); What if I told you that the Highland army at Culloden in 1746 wasn’t really a “Highland” […]