The Incredible Adventures of Algernon Blackwood

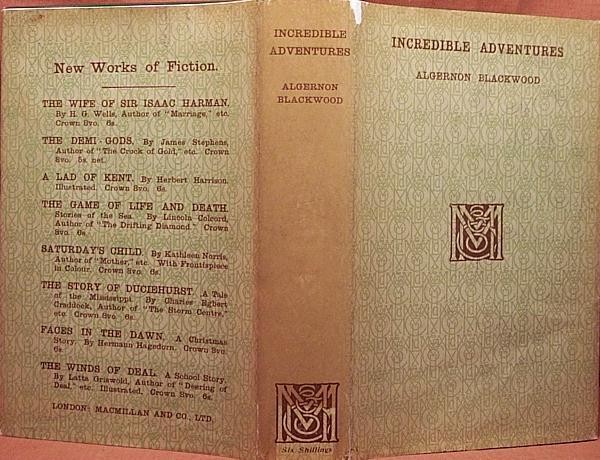

Incredible Adventures

Incredible Adventures

Algernon Blackwood (Macmillan & Co., 1914)

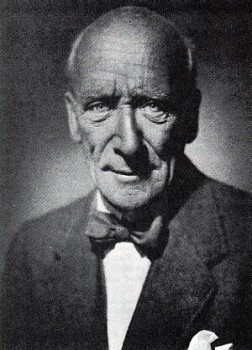

Of all the practitioners of the classic “weird tale,” which flourished in the early twentieth century before morphing into the more easily discerned genres of fantasy and horror, none entrances me more than Algernon Blackwood. Looking at the stable of the foundational authors of horror—luminaries like Poe, James, le Fanu, Machen, Lovecraft—it is Blackwood who has the strongest effect on me. Of all his lofty company, he is the one who seems to achieve the most numinous “weird” of all.

Blackwood is often referred to as a “ghost story” writer; indeed, one current in-print volume is titled The Best Ghost Stories of Algernon Blackwood. But true ghosts rarely appear in his fiction. Blackwood liked to dance around the edge of easy classification, and as his work advanced through the 1900s and into the teens, it got even harder to pinpoint. Blackwood’s interest in spiritualism, his love of nature, and his pantheism started to overtake his more standard forays in supernatural terror. His writing turned more toward transcendentalism and away from plot. The most important precursor to this development is his 1911 novel The Centaur, which critic S. T. Joshi describes as Blackwood’s “spiritual autobiography.”

The 1914 publication of the five novellas in Incredible Adventures marks the height of Algernon Blackwood’s career as an author of short fiction. He would publish further story collections and novels until his death in 1951, but Incredible Adventures is the critical high-water mark. It’s also so bizarre a work that even considering later movements in post-modernism and experimental writing, I don’t think any publisher would release anything like these stories today. Blackwood was both ahead of his time and already in another dimension.

Writing about the specifics of Incredible Adventures is akin to trying to describe a piece of music using semaphore flags. There simply is no effective way to do it. Nonetheless, I’m going to make an attempt to tackle each of the five stories, three of them extremely long, that Blackwood presents.

The Regeneration of Lord Ernie: Lord Ernie is the young son of the Scottish Secretary of State, and although a pleasant enough youth, he lacks any passion in life. “Yet all the machinery was there, one felt if only it could be driven, made to go. It was sad. Lord Ernie was heir to great estates, with a name and position that might influence thousands.” It falls to his teacher, John Hendricks, to try to inspire some lust for life in him during a long trip. However, nothing seems to inspire the boy until their last stop in a village in the Jura Mountains of Switzerland (near where Blackwood lived during the time he wrote the story) to visit Hendricks’s friend, the pastor M. Leyins. A strange pagan worship still exists in the hills, and according to Leyins the followers welcome the power of Wind and Fire. When Lord Ernie seems to feel a rush of energy from the mountain winds, Leyins suggests to Hendricks that they allow the boy to visit one of the ceremonies, so that he might be filled with their passion, and then they will snatch him away before it consumes him.

The premise is certainly a eccentric one—something the reader will need to get used to in Incredible Adventures—and only a writer like Algernon Blackwood could possibly carry it off convincingly. It feels drawn-out at the conclusion, but Blackwood can uphold the story through pages of abstract wonderment. The epilogue, the only place where the story actually “steps back” for a moment from the turmoil, is very effective.

The Sacrifice: This is one of the two shorter works in the volume, and it returns to familiar territory of the transcendental experience through mountain-climbing; but this is a more intense and personalized work than “The Regeneration of Lord Ernie.” Blackwood describes a complete religious confrontation in the cathedral of the great mountains (probably the Swiss Alps again), where his protagonist Limasson faces his nebulous personal gods whom he had thought to deny after a series of unspecified catastrophes beset his personal life. An invitation from two strangers at his hotel for a climb up the very mountain that Limasson has already planned to traverse the next day changes into a ceremony the higher they ascend:

This idea that they took part together in a Ceremony established itself firmly in him, with the added wonder that, though so often done, he performed it now for the first time with full comprehension, knowledge, truth. Empty of personal desire, indifferent to an ascent that formerly would have thrilled his heart with ambition and delight, he understood that climbing had ever been a ritual for his soul and of his soul, and that power must result from its sincere accomplishment. It was a symbolic ascent.

These words are a summation of Blackwood’s attitude toward mountain climbing as a religious act. And for both Blackwood and his character Limasson, “religion” denotes a spiritualism free from societal constraints. Limasson is one of the author’s wonderful dreamer characters who faces a crisis of belief. At points, “The Sacrifice” seems as if it might veer toward more standard suspense, but the climax and denouement are genuinely surprising and beautiful. Nobody can describe the awesome majesty of the mountains in the manner of Algernon Blackwood. Even readers who know nothing about the author’s life will guess after these two stories that he ardently loved mountaineering.

The Damned: This is longest of all the stories. It is also one the most bizarre novellas I’ve ever come across. It defies the idea of “plot” and “events” to the point that uneventfulness is one of its stated themes! What makes this amazing is that, at various points, “The Damned” seems on the edge of launching into a full-blooded supernatural horror tale, a haunted house shiver story. But yet nothing ever happens. And “The Damned” is quite proud to tell you that, over and over again.

The Damned: This is longest of all the stories. It is also one the most bizarre novellas I’ve ever come across. It defies the idea of “plot” and “events” to the point that uneventfulness is one of its stated themes! What makes this amazing is that, at various points, “The Damned” seems on the edge of launching into a full-blooded supernatural horror tale, a haunted house shiver story. But yet nothing ever happens. And “The Damned” is quite proud to tell you that, over and over again.

Siblings Frances and Bill, an artist and a writer respectively, receive an invitation from Frances’s friend Mabel to leave London and come stay with her for a month in the Sussex mansion known as The Towers. Mabel’s husband left the villa to her after his death. Bill, who serves as the first-person narrator, describes Mabel’s husband, Samuel Franklyn, as a philanthropic but puritanically narrowed-minded man: “All the world but his own small, exclusive sect must be damned eternally—a pity, but alas, inevitable. He was right.” This is an example of the dislike that Algernon Blackwood had for organized Western religion, an outgrowth of his own childhood in the strict Moravian Brotherhood and his relationship with his father, who feared for his son’s soul when the boy became interested in Eastern mysticism.

Bill turns down the invitation to live in The Towers, but Frances decides to accept and go stay with Mabel. Soon after, Bill receives letters from his sister that subtly indicate that something not quite right is occurring in The Towers, so he decides to go out there as well. Bill soon starts to get the strangest sensations about the place, a stifling feeling of “nothing happening” that Bill calls “the Shadow.” However, he (and by extension, Blackwood) indicate that nothing as prosaic as a “haunting” is occurring within the manor, no simple lingering effect from the ghost of the previous owner. The story expends great detail trying to describe the almost indescribable patina of unease:

…this idea of resistance to the natural—the spirit that says No to joy. All over it I was aware of the effort to achieve another end, the struggle to burst forth and escape in free, spontaneous expression that should be happy and natural, yet the effort for ever frustrated by the weight of this dark shadow that rendered it abortive. Life crawled aside into a channel that was a cul-de-sac, then turned horribly upon itself. Instead of blossom and fruit, there were weeds. This approach of life I was conscious of—then dismal failure. There was no fulfillment. Nothing happened.

Indeed, the continued funereal ring of the words “nothing happened” is the story’s core. This isn’t criticism, for “The Damned” is too unusual to give over to critical damnation, but it creates one of the most nebulous concepts of a threat I’ve ever come across in the “weird story.” To the very end, Blackwood is aware of the effervescent nature of this completely bizarre piece of the fantastic: “A novelist might mould the queer material into coherent sequence that would be interesting but could not be true. It remains therefore not a story but a history. Nothing happened.”

If “The Damned” has a concrete layer, it’s Blackwood’s disgust with what he sees as the destructive power of creed and dogma. Where in the other stories in this volume he expands on his spiritualistic and pantheistic beliefs, here he turns the other direction and condemns religious thinking that “excludes,” and ends up annihilating creativity and humanity through bigotry. “The Damned” of the title are really those who damn others, such as Mabel’s dead husband and all the people who had previously owned The Towers did. Although the story is no angry polemic—remember, nothing happens—the author’s position on organized religion is clear. That Moravian Brotherhood must have really damaged young Algernon.

A Descent into Egypt: Blackwood developed an obsession with Egypt a few years before Egypt became chic in the 1920s. However, as with the popularization of Egyptology in Europe and North America that followed the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, the Ancient Egypt of Algernon Blackwood is a peculiar creation, not necessarily a reflection of an historical reality, but of an interior Egypt, a personal view of the wonder of the Pharaohs, their gods, and their monuments. In “Descent into Egypt,” Blackwood launches a hallucinatory description of the all-consuming power of his personal mystery Ancient Egypt through the experience of one man, George Isley, a walking shell of a human drained by the Land of Nile.

Modern Egypt, he [Isley] explained, is, after all, but a trick of civilisation, and there was a kind of breathlessness in his measured tone, but ancient Egypt lies waiting, hiding, underneath. Though dead, she is amazingly alive. And you feel her touching you. She takes from you. She enriches herself. You return from Egypt—less than you were before.

The unnamed narrator meets with Isley in Egypt and experiences the man’s descent until only the outer part of him can return. This spiritual descent occurs over a remarkable night in Thebes, when the narrator, Isley, and Egyptologist Moleson gather to witness the engulfing power of the ancients. It begins with an extended musical exploration of a “Hymn to Ra” that contains astonishing descriptions of music that would seem impossible on the page. Then the three men move across the sands amid the devouring wonder until the narrator manages to pull himself back from the gulf into the present. As for Isley, “The distinctness, the reality, were appalling. He was naked, robbed, undressed. I saw him a skeleton, picked clean to very bones as if by an acid. His life lay hid in the being of that mighty Past. Egypt had absorbed him. He was gone….”

“A Descent into Egypt” mirrors “The Regeneration of Lord Ernie”; a person’s soul is taken away instead of receiving an elevation. But although the narrator shows dismay and shock at what happens to George Isley, the reader is allowed to understand that what happened to the man isn’t a damning of any kind. Moleson tries to explain to the narrator: “The soul, I suppose, has the right to choose its own conditions and surroundings. To pass elsewhere involves translation, not extinction.”

Wayfarers: The shortest of all the stories, and also the most conventional—although that’s relative to the other works here. The narrator, while on the way to meet a friend for a mountain-climbing expedition (Blackwood had to shoehorn in mountaineering somehow), gets in a motorcar accident that jolts him into an apparent past-life as a Frenchman during the Napoleonic Wars. Convalescing from a bullet-wound, “Félix” is tended to by Marion, his great love. Marion loves him as well, but she is married. The two finally unveils their grand love for each other in sweeping romantic statements, but Marion realizes that this is a recurrent romance throughout time. Nothing about “Wayfarers” is particularly original or surprising, but at least the poorest piece in the volume is also its shortest.

The sum of Incredible Adventures is hard to categorize according to bookstore-shelving techniques. To the modern sensibility, the contents fall under the aegis of fantasy, but contemporary readers aren’t likely to react well to Blackwood’s ditching of the standard mechanisms of story in his search for spiritually transformative work. Just “The Damned” alone is guaranteed to drive most readers unaccustomed to Blackwood’s themes into a frenzy as it defiantly does nothing. The feeling of these pieces is close to that of automatic writing, as if Joan Miró had taken to prose. Blackwood’s words unfurl in a slow dream of experiences of the inexperienceable. The talent he displays here is staggering, even if it causes bewilderment and occasionally outright frustration.

Is Incredible Adventures Blackwood’s masterpiece? I’m going to be a dissenter in this case. In my view, Blackwood achieved his finest work in his earlier collections The Listener and Other Stories (1907), John Silence—Physician Extraordinary (1908), and The Lost Valley and Other Stories (1910), where he combined his weird adventures with aspects of horror and fear. These earlier classics are supernatural horror, but are also superb works of mood. The stories and novellas in Incredible Adventures, on the other hand, may be remarkable, but I admire them more than I actually enjoy them. Their audacity in doing everything that short stories supposedly shouldn’t do is majestic, but lacking the residue of fear that appears pieces like “The Willows,” “The Wendigo,” and “Ancient Sorceries,” they don’t have as potent an impact, nor to they create a sense of development and movement. Nonetheless, you will find few other work in the literature of weird quite like these Incredible Adventures.

[…] on this site when I reviewed his most unusual collection of fantasy tales, the uncategorizable Incredible Adventures. I’ll now turn the clock back to one of his earliest original collections, a volume that is a bit […]

[…] his review of Incredible Adventures, Ryan Harvey saluted Blackwood […]