Black Gate Online Fiction: “Seven Against Hell”

By Janet Morris and Chris Morris

This is a complete work of fiction presented by Black Gate magazine. It appears with the permission of Janet Morris and Chris Morris, and New Epoch Press, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Copyright 2014 by Janet Morris and Chris Morris.

[Diomedes] fights with fury and fills men’s souls with panic.

I hold him mightiest of all; we did not fear even their great

champion Achilleus, son of an immortal though he be, as we

do this man: his rage exceeds all bounds, and none can vie

with him in prowess.

— Homer, The Iliad

These poets in hell account me ‘second best’ of the Achaeans, after pouty Achilleus. How is that? I killed more Trojans than he upon Troy’s battlefield, yet never committed hubris. I partnered with Odysseus on the night hunt. My aristeia, my excellence in combat, at Ilion was unsurpassed. I even stole the enemy’s best horses. Although I was the youngest warrior-king among the Argives, I won more than my fair share of glory. Poets through the ages extolled my battle: Homer, Hesiod, Aeschylus, Colophon, Sophocles, Antimachus, Appolodorus, Virgil, Ovid, Pausanias, Dante, Marlowe, even the loutish William Shakespeare, barely a man himself, praised my valor.

When Shakespeare’s wittol Marlowe recast Ovid’s Elegia, he wrote of me:

Tydides left worst signs of villainy;

He first a goddess struck: another I.

Yet he harmed less; whom I professed to love

I harmed: a foe did Diomede’s anger move.

So why am I in New Hell, you ask, sitting on this rise called the Devil’s Mound, above the infamous Damned Meadow, a sheep field boasting a clamshell stage where perdition’s self-appointed greats come to outshout one another’s verses?

True it is that on the battlefield of Troy in a single day I killed Astynous, Hyperion, Abas, Polyidus, Xanthus, Thoon, and two of Priam’s sons, Echemmon and Chromius. And I wounded Aphrodite, but at Athene’s order. And attacked Apollo. Twice. Thus I became the only man to wound two Olympians on one day in that battle. Notwithstanding, the worst I ever did on my own account was to steal the Trojan Palladium, their statue of Athene, with my bloody hands: yet without that theft, said the oracle, Ilion would never fall. So we took it, Odysseus and I, and this exploit brought Odysseus and myself not to Elysion with her bright blue sky and starry nights, but to Tartaros, to Erebos, thence to stinking New Hell City, here where the worst of the damned prey upon one another.

This hell of the New Dead is more proliferate than Achaea, vaster than all of Hades’, and full of pitfalls as grave as the love of a faithless woman — or any woman, since faithless all will be: my queen Aegialia proved that more than once.

Even a man such as I, who founds ten cities and is worshipped in his day and thereafter, can end in Erebos or Tartaros or worse. Thus here I am, with my fellow Epigoni — sons of heroes, accursedly forgetful of our valor: Until we drink the blood of earthly sacrifice we don’t recall our names, despite all that Mnemosyne, the waters of Memory, can do to prompt us.

So here I await a hero’s coming, in New Hell’s foulest park, while flocks of damned souls crowd and churn below me, hoping to find a patch of grass near the clamshell where the poetry contests will be held.

No matter what you’ve heard, it was Homer who in seven thousand lines told my Epigoni’s story, the tale of us seven heroes’ sons avenging our fathers’ deaths upon all of Thebes, commencing: “Now, Muses, let us begin to sing of younger men…”

What modern scribbler could vie with that? What thewless mincer down alleyways in darkest night, what tattooed and pierced and wild-haired oaf of little use could sing a song of heroes, since these but talk and heroes do?

Above my head the vault is ugly today, pulsing like a fish belly when first you gut it, bloody and streaked with veins of purple and scarlet and black. Praise hides her glow. Paradise turns away her face, her fell light taunting those who’ll never bathe in the shining love of gods.

Gods love the loyal, the true, the honest, the brave; not these damned crusts and crumbs of stalest souls, who have deserted honor and lost all. I thought Pallas Athene loved me. Even wounded, an arrow deep in my right shoulder, at the hollow of my corselet, I fought as if she did. I won as if she did.

Where is Odysseus? Late, when battle waits in Tartaros, and so many wrongs to be put right? Or not coming today? But a gray-faced messenger had brought me word: “My master, great-hearted Odysseus, asks your aid to undo a grave injustice. On Devil’s Mound in Decentral Park in New Hell City, on the first day of the poetry festival, please await him.”

So I’d left my six Epigoni, all my shining brothers in arms, to rendezvous with crafty Odysseus here, who shouldn’t wander underworldly realms. And neither should my Epigoni, if courage counts for aught and vengeance is sweet to heaven. We are seven, all told: Aegialeus, son of Adrastus; Alcmaeon and Amphilochus, sons of Amphiaraus; Euryalus, son of Mecisteus; Promachus, son of Parthenopaeus; Sthenelus, son of Capaneus; Thersander, son of Polynices (who by our efforts became king of Thebes); and myself, son of Tydeus and Deipyle.

Comes a climber up the hill, a mystic specter under hell’s rufous vault, wrapped in a linen robe from head to ankle, dark and stiff as if with blood. This swinging stride devours ground; this posture tugs my memory; this creature comes onward like a demon or devil or worse, all black inside that hooded robe.

I sit where I am. Long in the underworlds has taught me to rise only for good reason: in eternity, a man conserves his strength.

The enshrouded thing reaches my hilltop and stands before me, cowled; looks down at me. Its cloak is soaked in black blood, now I am sure: I can smell it.

It calls me by name. I have been speaking English for thousands of years, but that facile tongue deserts me. I respond in Attic to this manlike thing: “What?”

I know it by its very first word, but it speaks on as I rise up and stand, fists balled, uncertain of what to do now:

“‘…to Tydeus’ son Diomedes, Pallas Athene granted strength and daring, that he might be conspicuous among all the Argives and win the glory of valor. She made weariless fire blaze from his head and his shoulders and urged him into the midst of battle, where most were struggling.’”

And these are Homer’s words, from his Iliad, which all we who fought at Troy know by heart; every line of its fifteen thousand, six hundred ninety-three is filled with our blood and death and courage. But this man is not Homer. I know him as I know my own heart, as a wheel horse knows its running mate, as a pack-wolf knows its leader, as a lover the voice of his beloved. Yet peer as I may, inside that hood I see no beard, no weathered skin, no flaring nostrils…

“Odysseus. What happened to you? Why are you drenched in blackest blood, my friend?”

“I am skinned, Tydides, master of the great war cry.” He lets his cloak fall open.

Tydides. So long since any have called me that, save my own Epigoni. I close my eyes against a horror man should never know: a walking hero drenched in pain, without a single bit of skin anywhere on his body that I can see.

His right hand, quivering with rawest flesh, reaches out to me. “Powerful Diomed, help me get my skin back.”

“How? When?” I want to meet his flesh with mine, clasp arms, embrace this man who, I had thought, became a god upon his death. I must do it. I grit my teeth and clasp that meaty forearm which for so long I admired when weathered skin and tawny hair enwrapped it. I can feel the blood pulse, and leach, and drip sticky onto me. I want to pull back but he is Odysseus; I am Diomedes: I cannot be less than he needs. Not now. Not ever. “Help you? Of course I will. Where is your skin? We’ll go together, as in former times, and steal back what was taken, or secure it by force of arms. I’ll bring all my brother Epigoni with me.”

So we stand that way, until Odysseus can answer with his peeled and suppurating lips: I hear the raspy breathing of this tortured soul. And in that sound, finally, I learn what torment can be. In that grip of his, so tight despite his pain, I grasp the horror of an afterlife of penance unending, even for this hero, this giant of a man, whom so many wept to emulate.

At last Odysseus speaks again:

“I cannot go; I am too weak. You must go for me. In the Pandemonium Theatre, my skin and the skins of other heroes hang as costumes for fops to wear. And every time one of them pulls my skin about him, such pain overcomes my body as could make a man pray for madness, or oblivion.”

Too weak? Odysseus? What dreadful anguish, this?

“We Epigoni will steal it back, then. We stole Trojan glory. We stole Aeneas’ horses. We stole the Palladium. We stole Ilion with our wooden horse. We’ll find your hide and take it back, and again you’ll wear it — proudly.”

Despite the agony in every iota of him, Odysseus clasps me tight against his chest. I feel him shiver. And I wonder, despite my words, if we can do this thing, under the noses of every devil and demon and lord of hell. And why the gods allow this travesty.

Sappho heard the clanking armor of Greek heroes cutting through the crowd toward her podium long before she saw them: she needed to finish her recitation. She could not yet look up. Much rested on winning this poetry prize, New Hell’s most prestigious.

When nearly done, she dared raise her head. The Epigoni, unmistakable, stood before her: men such as Nature never made in later days, armed and bold, with ready shields — and one with a shield licked by fire. That one must be Diomedes, with his father’s plain sword and the shield Athene had given him, which threw flame when he so commanded.

She hoped he liked her recital. She nearly stumbled over her final words, “‘…some say cavalry, some say an army on foot, some say a fleet of ships are the most beautiful sights on this black earth, but I say it is whatever you love best.’” Then she stopped, gaze demurely downcast, and bowed her head…

…while from under her brows she stared at those dauntless half-naked Epigoni; at Diomedes, most beautiful of all, and added, “…unless it be heroes that make a heart race in its breast.” She hadn’t added words to that line for eons.

The crowd roared. Thin-necked and thick-girthed, big-headed, soft and small, these were the poets of all the newer hells, and more: real bards from early days, true singers from the nether hells. This competition would not be won without a fight.

Sappho was not above theatrics: she’d take advantage of these heroes, come from nowhere. She stepped off the dais as the crowd clapped and stamped and cheered, and strode up to Diomedes. On one side of him stood Thersander, by his kingly bearing and gold breastplate; on the other, Sthenelus, Diomedes’ sturdy partner at war before the slanty walls of Troy. To call herself a poet, a soul must know her Homer, and the Theban Cycle, and more.

These warriors ducked their heads to look at her and she felt a girl again, felt what she’d felt for her ferryman again. Sometimes a woman, yes, but sometimes a man is what a woman needs, if that man be as heroic as these.

“Sappho,” she gives her name, suddenly uncertain. “Have the Muses brought you to aid me? Let me walk with you.” Heroes such as these surely were not here for entertainment.

“Diomed,” affirmed the one whose helmet had the longest purple crest, whose breastplate bore a gilded boar, who wore Athene’s shield of blessed fire on his arm. “Come hear our plea, honored poetess. We seek a favor.”

Poetess? A favor? So they knew precisely who she was.

The Epigoni swirled around her like a cloak and off they went, amid the awed mutters and whispers of this posturing crowd of poets. “A favor? Of course,” Sappho breathed, agog at the venture beckoning, more dazzling than any other — as were these heroes from Erebos. “What brings you to the lesser hells, heroes?”

“We brought our ancestor Andromeda up from Hades for the day, to enjoy your festival,” said Thersander, gallantly flattering her with a lie: no dark Andromeda walked among them, nor would they have left her behind, among the dross of ages here.

The Epigoni escorted her, Diomedes on her right, Thersander on her left, followed by the other five, spears bristling, close about her: what a finale, fit counterpoint for her presentation at the contest. If she didn’t win the poetry prize, no matter: she’d gained a greater prize here, on her left, on her right, at her back. More beautiful than aught else in the nether realms were these heroic souls. Behind her, a white-winged angel exhorted all participants in the competition, contestants and audience, to climb up on the clamshell stage and “mingle.”

Sappho looked back over her shoulder: some New Dead poet was spilling words that tumbled from his lips in fiery letters. Never mind: Sappho was headed somewhere else, with these seven warriors called the Epigoni. But … caution: she’d not taught school without learning something: “And that’s all you want, Epigoni? To enjoy the festival? Ask a favor? Diomed, is that all you want?” This Diomedes was a hero of lyric proportions, in his body, in the eyes of history, and now in her heart.

“I need a poet to pry loose from two poets something belonging to my friend, much-enduring Odysseus,” Diomedes told her.

“Ah, I see.” But she didn’t. Instead she saw Homer, almost completely blind today, poking his way along the hillside with a stick. “How about two poets?”

“Two?” Diomedes echoed low, in that voice famed for its great war cry.

“Great Homer,” she called, “attend us! And I shall be your guide to an exploit most rare.” Ancient body, bony face: Homer’s cloudy eyes shift and drill to the bedrock of her soul. Then the Ionian bard turned from the clamshell, from the crowd, and picked his palsied way up the rise toward them.

Just in time. For meanwhile, behind Homer, audience and contestants thronged the clamshell stage, until that stage could hold no more souls. Then the clamshell snapped shut around poetical woe, swallowing screams and wails of terror, while the huge bivalve spun and spun, and dug its way into the sheep field’s ground as if bedding itself ever deeper in a sandy seafloor.

Sappho stared past frail Homer, to the source of first cacophony, then complete absence of sound, until the burrowing clamshell with its catch of lyric souls completely disappeared and black ground covered it. She whispered, “Diomed, you and your brother Epigoni may have saved me.”

“As you saved long-remembering Homer?” Diomedes shrugged shoulders that could heft a world. “Happens all the time, Muse,” said the hero of Ilion, with his hand at the small of her back to guide her onward as Homer, squinting hard, joined with the Epigoni and began regaling all in heroic hexameter with his lost lines that sang their glory.

By this, Sappho knew she was stepping into something much, much more than simply another day in perdition. She closed her eyes and thanked her muse for putting her once again in the path of a story worth telling, among souls worth enshrining — and, more than all else, promising glories in hell which Sappho never would forget.

Pandemonium’s towering walls, built to discourage scaling, gave me pause and struck Homer fully blind with their majesty. Battlements greater than Ilion’s were these, black as the heart of their lord. In their shadow we planned our strategy as Paradise glowered baleful above, longing to set.

Mighty Thersander drew his bow and shot two grapple-hooked ropes over the spiky ramparts once we’d learned the pattern of the watch patrolling, cocky on their battlements, protecting Satan’s infernal seat. My war-partner Sthenelus and I clambered up those ropes as spiders scale their webs. And there we lurked until a pair of watchmen passed the crenel where we hid.

Lunging from cover, we overcame them in two strides, laid sharp bronze against their quivering throats, promising to free them once they told us the watchword. When we heard it, we broke both their necks where they stood, spilling not a drop of blood, stealing their mantles and helmets and throwing their naked corpses over the wilderness side of the lofty wall.

I’d done as much before, in the darkness, with Odysseus as my partner outside Ilion’s gates, so I found it fitting, even in this hellish place with no sun or moon, just Paradise still shining down.

For Odysseus, we would risk all and do all.

Now disguised as henchmen of the devil, we climbed down our ropes, back to our brother Epigoni, unnoticed in the black wall’s shadows: men guarding such a height hardly ever look straight down, but outward.

With our brother Epigoni and two poets, plus the watchword and our stolen cloaks and helmets, we were ready.

We walked right in, between the gate towers, using Sappho and Homer as our diversion, those two reciting epic verse in a rhythm to fascinate the coldest soul:

Homer sang his Iliad: ‘“O Muse, sing what woe the discontent/ Of Thetis’ son Achilleus brought the Greeks; what souls/ Of heroes down to Erebos it sent…’” And on, pausing only for Sappho to sing in turn.

And Sappho rejoined with her own work:

Then Helen, who outshone

All others in beauty, left a fine husband,

She sailed for Troy

without a thought…

Led astray…

Their singing caught everyone’s attention, and held it as we warriors passed by, unnoticed.

Soon enough we found the Pandemonium Theatre, hulking huge. None had missed the slain watchmen yet; no call to arms ripped the ruddy gloom. But we must hurry: soon enough, someone would.

“Alcmaeon and Amphilochus, guard this theatre entrance,” I told these long-haired brothers, like twins, both blond and brazen. Alcmaeon had led us against Thebes, but led us not today: on this foray, the Epigoni take my orders. “Euryalus, Promachus, circle around back and hold the rear door.” Those two had spitted their share before wide-walled Troy, and fought like bears rampaging. They’d keep clear our escape from this massive Pandemonium Theatre, big as a palace and tall-spired, so broad and lofty it taunts the vault of heaven. “Parthenopaeus, watch over Homer and Sappho with sharp bronze and quail not at any demon or wraith you see: pierce all comers. And look sharp about you for a wagon big enough to carry our poets and what heroes’ skins we find.” A rough-faced berserker he was in life and is in soul, and needs no help from any other. “Homer, Sappho, sing more songs, recite what verse you may, but keep all entranced; distract and delay them; let none get past you through this door.”

Blind Homer blinked at me. “Be certain we will, noble Tydides, daring breaker of horses. I’ll tell of you, your hungry valor, as my mind’s eye first saw it.”

“And I,” said Sappho with that voice like a brook in springtime. “‘Although only breath, words which I command are immortal.’” She’d said that before; I’d heard that before, but it is yet true. No time now, but later, if victory is mine, I’ll let her whisper in my ear. She added: “I’ll sing of you, how Helen chose you not, you so like a god in valor; how she fled her home…”

“Fine. You sing what you wish, Sappho.” I turned back to my own: “Sthenelus, son of Capaneus, you fight by me.” Sthenelus, once my charioteer and loving friend in life, showed his teeth. “Thersander, as we made you king of Thebes once, now you’ll bring your rage and help get back every hero’s hide from this foul barrow. Fight close behind me and Sthenelus, protect our rear, and help carry out the skins when we get them. And you, Aegialeus, mighty son of Adrastus, be as inescapable in our cause as was your father.”

At least no gods would take the field against us, I told myself, although hell has gods: gods of its weeping dead and its sleeping dead and its regretful dead.

“And all of you: we fight for the skin of Odysseus and perhaps the hides of many other heroes. We fight and die if need be, here where death is not the worst tithe we can pay. Hear my strategy: this is our duty, to put an end to the skinning of heroes by those who believe not in honor, or heroes, or anything at all. So when I give my war cry, storm in, all but Parthenopaeus, who’ll bide with Sappho and great Homer.”

“But — ” Sappho objected. “We want to go in with you, see the fighting, to sing a song of glories won — ”

For centuries few have dared interrupt me; I found my grip on my spear too tight. Angry words burst from my heart: “You’ll do as you’re told, poetess. Now, stay.” My rage came hot upon me, pounding in my heart and firing up my brain, making a mist before my eyes as bloody as the vault above. But before I could reach through fury for kinder words, old Homer spoke:

“Sappho of the best-chosen phrases, we are here to use poetics to help save the skin of my grandfather, crafty and unparalleled Odysseus. What we must do, we will do: recite epic verse to ensnare the boldest soul. What we can’t see, we’ll not see: hard for you, easy for me. And these heroes will honor not only my grandfather, but your words and mine. Respect wild-hearted Diomedes, ready for war; recall this man, who fought the immortals and returned home to an unfaithful wife after the fighting and the bitter warfare. And be silent now, knowing you are graced as no other woman, to be here.”

I said nothing more, but my fingers loosened on my spear. Blind, Homer may be, at the whim of gods and devilish demons, but he sees too much.

I leveled my ash spear. At that signal, the Epigoni deployed, stealthy and unerring, until only Sthenelus remained with me.

Using great Homer and the poetess for our diversion: would the gods of hell take umbrage at my plan? And if they did, would they come fight against me? I’d skewered Apollo and Aphrodite and survived. Aye, let them come, angry demons or devil or underworldly gods. If they dare.

Up adamantine stairs we strode. I adjusted my shield of fiery nature that Athene had given me in life; I keep it always with me; I was buried with it. At least none had asked me how we would fight our way out of Pandemonium with our prizes of precious hide: this city, full of warriors, is vast and labyrinthine, Satan’s devilish seat.

Thus far, none opposed us, late in the day with Paradise glaring close above spike-topped crenels. In we go, charging, pushing oak doors apart, shields on our left arms, purple-plumed helmets on our heads.

Quiet it is, inside this dark place, where torches flicker as the doors behind us slowly shut. We pass a choke point, where someone should be to say who can enter, who cannot. Today no one stands there.

Every sound here is far too loud, down a stone-walled corridor that opens onto a stage before rows of empty seats. Our sandals echo; I can hear my own breathing, far too loud. I touch Sthenelus’ arm and take off my helmet; he does the same.

We vault onto the stage, spears ready, and I want to draw my sword, cut empty air to ribbons. We search, poking and prodding curtains with our spears and shields, until we find a way behind them.

Here all is quiet; here there are ropes and rigging and eye-whites disappearing into shadows far above us, where I hear stirrings as if birds are nesting or panthers hiding on cedar rafters; here is the stench of creams and unguents and stale sweaty bodies.

Hotheaded Sthenelus looks up and stabs overhead as high as he can with whetted bronze on ash shaft. Something skitters. Sthenelus looks at me askance.

Angling my shield upward, I slap my spearhead twice against this shield Athene gave me; a gout of flame billows forth, and up, toward whatever might lurk aloft.

Scuttling and scrabbling increase overhead among the rigging, but no hellish creature drops upon us from those high rafters; no Erinys or Ker or winged beast; nothing dares Athene’s flame — or nothing cares to try.

Then we find stairs leading downward into narrow corridors: the worst fighting joins always in close quarters, corridor to corridor, room to room.

Sthenelus lifts his hand in caution: he’s heard a sound; I hear it too. We make that way, and are rewarded as we burst in together, shoulder to shoulder, splintering oaken doors off their hinges:

Two men cry out, scramble from their table where they work by candlelight, till they feel walls against their backs. One is braver; this one stands before the other: “Who are you? What do you seek?” His is the face of a child, with but a wisp of beard curling round his womanly mouth; yet he stands before the other man, arms spread — and I see a child’s dagger in his hand, glinting in the torchlight from their worktable.

This room has no windows, no other door: these two men in their hose, with their curled hair and goats’ beards and their puffy pants, are trapped.

“We are Epigoni, here for the skin of wise Odysseus, and more. What we want is every hide stored here, of every hero from former times. Or we’ll take your skins instead, without even knowing who you are, or caring.” This is not a worthy battle; these are soft, pale men. The better of the two holds the dagger. I could spit them both in two heartbeats.

I heft my spear.

“Wait,” says the prissy, knock-kneed one in green hose, with his hand upon his protector’s shoulder. “I know you!”

“Wait for what?” Sthenelus says upon a snarl. “You know us? So? All men should know their executioners. You’re in our way. Men who stand between us and what we want soon die — even if you’re barely men.” He levels his spear. “Unless, of course, you lead us to those hides of heroes kept here — each and every one.”

“Satan is our taskmaster,” says the foremost. “We labor in his cause.”

“So what? My partner Diomedes has wounded gods. What care we for devils?”

The baby-faced man sidles left, his friend keeping pace, but Sthenelus too has him within range: one lunge, one solid thrust, and either of us can pierce both soft bellies offered under flimsy garb: run the first man through and skewer the second with the selfsame spear. These two are more women than men, and quail like it. “You’ll care if Satan shows his face here, spear-chucker,” warns the foremost fop, chin jutting.

The man behind that one said, “Diomedes, don’t you remember me?” as if crestfallen. “From the Hellfire Club? From the polo match? Do you not know how I wrote about you, having Aeneas say, ‘We know each other well,’ and you reply, ‘We do, and long to know each other worse.’”

I scoffed. “I knew Aeneas only well enough to steal his best horses, but if you’ve his skin here too, I’ll take it with me: even Aeneas, counselor of Trojans, is a real hero — not like you two.”

My words made Sthenelus bark: “We don’t care who you are or what you wrote, you womany thing. Will you give up Odysseus’ skin and the other hides of heroes that you have, every one? Or not? If I learn you’ve ever donned that skin of Odysseus, or any of our fellows flayed by evil, I’ll skin you both here and now and find a dog and bitch to wear the both of you.”

One of them let gas, or worse: a stench wafted through the room.

So I said to the wide-hipped one, “Give me my friend’s skin, then, and the skins of all of his fellow heroes. You’re Shakespeare, are you? What of it? One more dead poet who dreamed of being me.”

“We cannot give up those costumes, Will,” said the other man, the fitter of the two, screwing up his baby face and whispering softly to his friend: “They’re Satan’s props. Or can we?”

“We must, Kit,” hissed Shakespeare, hiding behind his friend. “Sheathe your blade, Kit Marlowe. A visit to the Undertaker, run clean through, is not on my agenda for today. Or yours, if I can forfend it. I will bear responsibility, explain to His Infernal Majesty.”

And so I gave my war cry for gathering, and all my Epigoni came to help carry away the skins of heroes that these girly-men had in their closets, Homer panting but keeping pace, as by touch and Sappho’s descriptions he identified each hero’s skin.

When out of their closet these prissy boys pulled skin after skin, my heart beat faster. We would need to range far and wide in hell, to give this score of skins back to those who’d grown them.

The sight of so many heroic hides on hooks was so awful that Thersander retched, spitting bile into his blond beard. But we managed.

And all the while they brought us skins, those two fops gibbered to each other about who we all were: about Sappho and Homer and the seven Epigoni.

“You Epigoni and you poets,” said the one called Marlowe, “be assured that Satan will come after these skins, and all of you for damnable theft.”

“Homer and Sappho had no part in this,” I lied. “We abducted them, to make sure we knew whose skins we took. And as for your devil and his minions, bring them on. We are only seven, but we are the Epigoni, and if that makes seven against hell, think what the plague god Erra and his Seven, the Sibitti, have done to bring infernity to its knees. What we can do, let Satan come and see.”

Soon we left, stealing a wagon from behind the stage and sneaking out the back door of Satan’s Pandemonium Theatre with the blind bard and the poetess perched atop twenty skins of heroes known from former times, and Thersander retching, and Sappho singing, and Homer crowing our glory, and Sthenelus steady by my side.

I kept my fire-spitting shield by the wagon with its gory cargo the whole time, but Sthenelus and I still wore our stolen mantles, thus we strode right out the gate.

An arduous task ahead, to deliver all these skins safely to their owners throughout the netherworlds. First we’d give Odysseus his hide back, then seek the others. Already I was planning our next move.

In hell, where forever weighs upon the heart, few deeds are fit for honorable souls, but returning a hero his skin is worth doing, no matter the cost.

I can hardly wait to see Odysseus’ face…

…and when I do, I see a strong man weep. Even in hell, this is a sight more awful to behold than most souls can bear.

He touches his skin, puts his hands on that boneless countenance, then on the flesh of his raw and bloody face. He shakes out his body’s skin as he stands there, and if I could I would help him.

But this mastermind Odysseus, this great-hearted sacker of cities, is brought low. With a stifled sob he puts one foot down one leg of that hide, then the other.

Next he lets his cowled robe fall away, and I see yellow and white and purpled bone and meat and recall Thersander, retching.

There is nothing to say, nothing I can do but watch as mighty Odysseus with trembling limbs pulls his skin up, and up, and wriggles his hips, and smooths the eyeless hide over his face and head.

Comes a puff of wind, a blink of lightning…

…and here stands Odysseus, man of pain, great glory of the Achaeans, as he always was and should be, his gory linen shed and lying black with crusted blood around his feet.

He rubs his face, puts trembling fingers to his mouth, and says to me haltingly through lips once again his own, “Diomed … are there more of us, enduring this?”

“More,” I tell him. “I have a cartful of hides that quiver and stink, bereft of bone and meat and man.”

“Then what are we waiting for?” Odysseus looks at me from bloodshot eyes, picks up his stiff and blood-soaked cloak and wraps himself, then gives a cry to curdle all the blood in hell.

That cry resounds, carried on an ungodly wind far and wide. It reverberates inside my soul and wends away.

Now once more all the Epigoni will gather, and every skinned hero in hell will know we’re coming.

I can taste the blood of war upon the air.

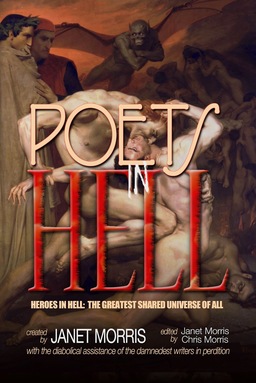

“Seven Against Hell” is just one story from

Poets in Hell, edited by Janet Morris and Chris Morris

Learn more here