Fiction Review: Dossouye by Charles R. Saunders

By Bill Ward

Copyright © 2008 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

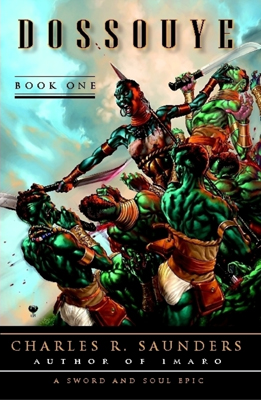

Dossouye

Charles R. Saunders

Sword & Soul Media, 198 pages, April 2008, 19.95

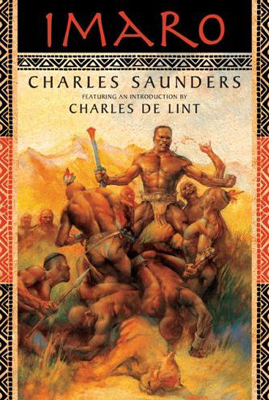

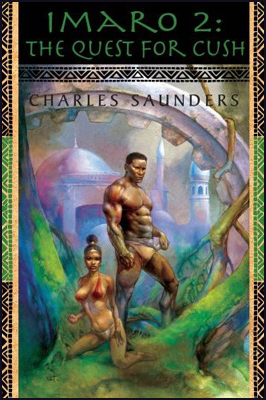

Newcomer Sword & Soul Media aims to prove that three times really is the charm with its planned release of the as-yet-unpublished concluding volumes of Charles R. Saunders’ superb Imaro series, finally completing an epic that began twenty years and two publishers ago. But Imaro is not the only fantasy hero of Saunders’ who will finally be getting their due, for Sword & Soul have just come out with Dossouye, a collection of stories old and new revolving around a female champion every bit as formidable — and as carefully realized — as Saunders’ legendary Ilyassai warrior.

Dossouye begins with “Agbewe’s Sword,” a novella-length tale that introduces Dossouye and her world with the deft touch characteristic of Saunders’ writing. After only a few pages the reader is fully immersed in Dossouye’s world, learning of its grand rivalries and more intimate antagonisms, its peoples, traditions, and potent magics. Inspired by the historical cultures of West Africa, the environment of Dossouye has an authentic, richly rendered quality familiar to those who have read Saunders’ Imaro, a setting that both sets a wonderfully evocative tone and informs the motives and perceptions of the characters and societies that inhabit it. Saunders does not use his setting as mere window-dressing, but instead infuses all levels of his story with the kind of vibrant sense of place that makes his world come alive.

The reader enters this world on the eve of a catastrophic defeat for the army of Abomey, Dossouye’s people, a defeat inflicted by enemy sorcery. Dossouye, a soldier of the ahosi, Abomey’s corps of women warriors who are literally considered the brides of their Leopard King, survives, as does her steadfast and constant companion Gbo, a war-bull of semi-tame water buffalo stock. But so to does Nyima, the commander of the ahosi and onetime rival of Dossouye’s mother, who hates Dossouye with a dangerous intensity and seeks to thwart her even at the expense of the kingdom.

The reader enters this world on the eve of a catastrophic defeat for the army of Abomey, Dossouye’s people, a defeat inflicted by enemy sorcery. Dossouye, a soldier of the ahosi, Abomey’s corps of women warriors who are literally considered the brides of their Leopard King, survives, as does her steadfast and constant companion Gbo, a war-bull of semi-tame water buffalo stock. But so to does Nyima, the commander of the ahosi and onetime rival of Dossouye’s mother, who hates Dossouye with a dangerous intensity and seeks to thwart her even at the expense of the kingdom.

Abomey must resort to magic, to vudunu, and hope that its gods and ancestors can prove up to the test of defeating the enemy that threatens to destroy it. But Dossouye receives a vision in a dream from the first ancestor of her clan, Agbewe, and embarks on a quest for that ancestor’s sword that is complicated by the rivalries within her own clan. “Agbewe’s Sword” juxtaposes the large events of politics, war, and quest with more intimate themes of friendship, jealousy, and tradition to create an adventure with a depth not often seen in Sword & Sorcery fiction.

I won’t spoil the resolution to “Agbewe’s Sword,” I will only say that the story sets Dossouye on her path of voluntary exile from her people. Together with Gbo, she wanders far from home, and the remaining stories in Dossouye are episodes in her rootless life. However, the book should not be thought of a collection of unrelated stories, for Saunders’ has taken pains to combine them into an episodic novel, writing new stories and rewriting old ones, so that the whole of Dossouye is cohesive and integrated within an overall structure — one really cannot sample these stories out of order as could be done with a volume of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser or Elric tales.

In her further adventures there is of course hard fighting, and dark magic, and encounters with beings strange and wondrous. Saunders is adept at pacing, and writes with the strength and verve of the pulp tradition without inheriting its faults. But it’s the unexpected elements of Dossouye that I think deserve special mention for, in a story that works so well as adventure fantasy, there is a great deal more going on just beneath the surface.

In her further adventures there is of course hard fighting, and dark magic, and encounters with beings strange and wondrous. Saunders is adept at pacing, and writes with the strength and verve of the pulp tradition without inheriting its faults. But it’s the unexpected elements of Dossouye that I think deserve special mention for, in a story that works so well as adventure fantasy, there is a great deal more going on just beneath the surface.

Imaro was born as the antidote to so many of the shallow stereotypes of Africans in pulp fiction, and Dossouye of course continues in this vein by presenting a capable protagonist in a complex and multi-hued alternate Africa setting. But Dossouye also subverts the perhaps even more pervasive stereotype of the role of women in Sword & Sorcery and Heroic Fantasy, while avoiding the perils of overcompensation or banner waving. Dossouye is neither a collection of hyper-feminine characteristics, a man in drag, or a clumsy attempt at a superwoman — she is instead as authentically drawn as the world she inhabits, a believable woman warrior who wears both mantles with a naturalness that is testament to Saunders’ insight, craft, and good taste.

The role of tradition in society is a central theme in Dossouye, one that is addressed in a thought-provoking and often surprising way. Dossouye, herself having discovered that not everything she took for granted in her traditional upbringing was true, encounters several cultures not her own that she views with an outsider’s appraising perspective. In “Shiminege’s Mask,” she wisely and wilily maneuvers within a villages’ existing tradition to free them from a parasitic evil, and only when a more direct approach, the revelation of the truth of her interference, is tried does her effort meet with defeat. The role of tradition is also central to perhaps my favorite story in Dossouye, “Yahimba’s Choice,” which deals soberly with the odious practice of female ‘circumcision’ within a society, and the brave choice of a young girl who must undergo the rite. Dossouye, having seen much that she would choose to oppose and herself free from many of the mores or limitations of the various societies she encounters, still has the wisdom to consider the importance of tradition and community for the members of those cultures — a refreshing change from many of the current crop of two-dimensional heroes in fantasy fiction, who indulge in personal crusades divorced of all consequence to those around them.

Saunders doesn’t shy from showing the consequences of actions in Dossouye, and this refusal to dumb down gives the book much of its resonance and realism. Dossouye pays a price for her heroism, for her estrangement from community, and even for her honesty in the face of tradition. In “Obenga’s Drum,” the final story in this collection, Dossouye confronts the consequences of her many actions and must accept both her mistakes and successes. Dossouye, alone in the world and severed spiritually from her people and ancestors, at last earns a kind of peace through the magic of a stranger who himself has suffered deeply. In the final scene of the book Dossouye continues her journey, but, having gained an understanding of herself, and a vision that reaffirms her ties to her ancestors, is perhaps herself no longer lost.

Saunders doesn’t shy from showing the consequences of actions in Dossouye, and this refusal to dumb down gives the book much of its resonance and realism. Dossouye pays a price for her heroism, for her estrangement from community, and even for her honesty in the face of tradition. In “Obenga’s Drum,” the final story in this collection, Dossouye confronts the consequences of her many actions and must accept both her mistakes and successes. Dossouye, alone in the world and severed spiritually from her people and ancestors, at last earns a kind of peace through the magic of a stranger who himself has suffered deeply. In the final scene of the book Dossouye continues her journey, but, having gained an understanding of herself, and a vision that reaffirms her ties to her ancestors, is perhaps herself no longer lost.

Sword & Soul Media have done an excellent job bringing Dossouye to print — the layout, design, and copy are all top notch. Printed as a POD from Lulu, I can attest that the book, a perfect-bound trade paperback, is handsomely done and sturdy, with no discernable signs of wear after my somewhat ungentle reading and book marking. The scintillating cover art of Mshindo Kuumba deserves special mention for its otherworldly kineticism. If Sword & Soul’s future offerings continue to live up to the high standard set by Dossouye, then fans of quality fantasy can rejoice that Charles R. Saunders tragically neglected works of fantastic fiction will at last get the attention they deserve.

equestrian murder for hire plot