Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars, Part 6: The Master Mind of Mars

I maxed out on Barsoom back in March. After reviewing the first five Martian novels over a span of two and a half months, I switched over to writing about the movie John Carter of Mars. (That is what I’m calling it, dammit, because that’s what the end title card says.) I love the movie, but the box-office and the box-office pundits did not, and although I struggled to keep a positive view, I realized after all of this that I needed a break from Edgar Rice Burroughs’s red planet.

I maxed out on Barsoom back in March. After reviewing the first five Martian novels over a span of two and a half months, I switched over to writing about the movie John Carter of Mars. (That is what I’m calling it, dammit, because that’s what the end title card says.) I love the movie, but the box-office and the box-office pundits did not, and although I struggled to keep a positive view, I realized after all of this that I needed a break from Edgar Rice Burroughs’s red planet.

But during a brief pause between my summer movie reviews, the opportunity to zap my Earthly body back to Mars offered itself. So my overview of ERB’s Martian epic resumes at Book #6, with a new Earthman hero, a return to first-person, and the Barsoomian equivalent of The Island of Dr. Moreau.

Our Saga: The adventures of Earthman John Carter, his progeny, and sundry other natives and visitors, on the planet Mars, known to its inhabitants as Barsoom. A dry and slowly dying world, Barsoom contains four different human civilizations, one non-human one, a scattering of science among swashbuckling, and a plethora of religions, mystery cities, and strange beasts. The series spans 1912 to 1964 with nine novels, one volume of linked novellas, and two unrelated novellas.

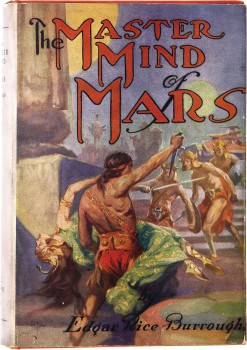

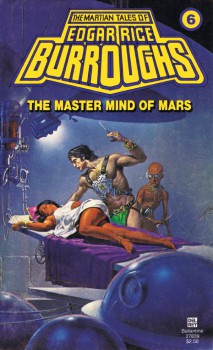

Today’s Installment: The Master Mind of Mars (1927)

Previous Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913-14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The Chessmen of Mars (1922)

The Backstory

Burroughs wrote The Master Mind of Mars (originally under the less thrilling titles “A Weird Adventure on Mars” and “Vad Varo of Barsoom”) in mid-1925, but his usual markets didn’t pick it up. (Wikipedia, in a [citation needed] moment, speculates this may have something to do with “its satirical treatment of religious fundamentalists.” That seems unlikely, as the book is light on the religious criticism compared to the instant-selling The Gods of Mars, where searing attacks on religion are the center of the plot.) ERB finally sold the book to Hugo Gernsback, inventor of the term “science fiction,” pioneer of magazine SF, and notorious cheapskate, who paid $1,250 for the novel — much less than what the author got from his usual markets. Gernsback made Burroughs’s newest Martian adventure the lead story for his Amazing Stories Annual, an extension of what was at the time the only science-fiction pulp. Burroughs made sense as a circulation-booster, since he helped create magazine SF fourteen years before the first pulp dedicated to it appeared on the stands.

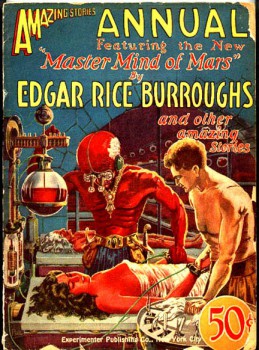

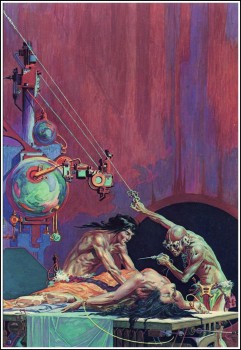

Amazing Stories Annual appeared in July 1927, crammed with top authors such as A. Merritt (Burroughs’s closest competitor for popularity at the time) and H. G. Wells, but Burroughs’s The Master Mind of Mars took the cover — a great piece of phantasmagoria by Frank R. Paul — and his name was printed as large as the magazine’s title. Burroughs made the issue a bonanza that sold out on the newsstands. By March of next year, A. C. McClurg had the hardback out for eager fans.

The Story

The Story

Captain Ulysses Paxton of the U.S. Army loses his legs on the fields of France during the war. While awaiting his death, he gazes on the planet Mars, thinks about his warrior-worship and his Edgar Rice Burroughs fandom, and bam!… he’s on Barsoom, where he will be known as “Vad Varo.”

He arrives in the country of Toonol and becomes the guest/prisoner of Ras Thavas, the titular “Master Mind.” Ras Thavas works at embalming, surgery, and brain-switching in his laboratories, and Paxton serves as his assistant. At the request of Xaxa, the aging Jedarra of the nearby nation of Phundahl, Ras Thavas puts her brain in the body of a beautiful girl from his vaults, Valla Dia. Paxton falls in love with the girl’s body, and requests that Ras Thavas re-animate Valla Dia’s brain inside Xaxa’s old body, which the scientist does out of curiosity.

Valla Dia, trapped in a withered body, tells her sorrowful tale to Paxton: she was one the handmaidens to the Princess of Duhor, seized when an enemy prince attacked the city and the princess vanished. Valla Dia ended up sold into slavery with the rest of the princess’s retinue. Paxton swears he will restore the girl to her proper body and take her back to her home city.

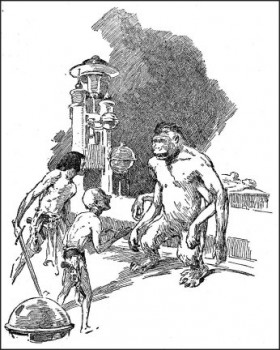

Paxton plots his escape, and uses his new medical skill to revive three allies from Ras Thavas’s laboratory: Gor Hajus, a top assassin of Toonol; Dar Tarus, who has a vendetta against Vobis Kan, jeddak of Phundahl; and Hovan Du, a white ape with half of a human brain grafted into it. They steal away from Ras Thavas’s compound on a flier and reach the city of Toonol and safety in the home of a Mu Tel, a prince at odds with his father, Jeddak Vobis Kan. Mu Tel aids their escape toward Phundahl, where Paxton hopes to obtain the original body of Valla Dia that the vile Jeddara Xaxa stole from her, and perhaps also help his partners in the adventure get the brain and body-switching they need.

The Positives

The Master Mind of Mars ties with Thuvia, Maid of Mars as the shortest book of the series. Unlike Thuvia, which unrolled a sprawling plot between the great cities of Barsoom, The Master Mind has a compact story that fits well into the confines of a 50,000-word novel. The major nations of Mars remain on the fringes, and the action occurs in the limited space of Ras Thavas’s home and the nearby minor cities of Phundahl and Toonol. The personal conflict is more focused, and the dynastic squabbles never intrude far into Paxton’s quest to get Valla Dia back into her original body. Although Burroughs did not plan to publish the book in Amazing Stories Annual, the final work does feel as if its author wanted it to appear in only one installment. It’s definitely the least episodic of the Martian novels.

I enjoy what Burroughs achieved with the third-person narratives of the previous two books, but this was the right time to revert to first-person and an Earthling’s subjective view of the red planet. If Burroughs tried to go back to John Carter’s POV, it wouldn’t have worked — we’ve had plenty of John Carter already. The creation of Ulysses Paxton was a good solution, and Burroughs gifts the new character with enough previous knowledge of Barsoom — as he mentions in his letter to the fictional-ERB that serves as the book’s prologue — that there is no need to do a re-introduction to the planet à la A Princess of Mars.

Paxton is a good variant on Carter: heroic but without Carter’s megalomania. He never shows near the same level of martial prowess, and the benefits of Mars’s lower gravity are so subdued in the writing that sometimes I think Burroughs might have forgotten about it. Paxton feels like someone who might get seriously injured, or fail to overcome even a small number of determined enemies. He’s the most realistic protagonist yet to appear on Barsoom, and that helps within the smaller scope.

The story wastes no time getting to its core. Readers of The Chessmen of Mars had half a book to plow through before any “chess” happened, but the titular mad surgeon appears in Chapter One and drops the readers right into his promised world of weird science. Paxton is only the second Earthman to reach Mars, but unlike A Princess of Mars, he has no time to wander the wastelands and adapt to Barsoom’s way: he immediately meets Ras Thavas and gets a tour of the embalming and brain-switching factory. Burroughs makes sure his readers know that Master Mind has new goodies to offer.

The story wastes no time getting to its core. Readers of The Chessmen of Mars had half a book to plow through before any “chess” happened, but the titular mad surgeon appears in Chapter One and drops the readers right into his promised world of weird science. Paxton is only the second Earthman to reach Mars, but unlike A Princess of Mars, he has no time to wander the wastelands and adapt to Barsoom’s way: he immediately meets Ras Thavas and gets a tour of the embalming and brain-switching factory. Burroughs makes sure his readers know that Master Mind has new goodies to offer.

Ras Thavas, the Dr. Moreau of Mars, makes an excellent and bizarre adversary, and for the first time the villain takes center stage. He appears the first moment Paxton materializes from Earth, and remains a constant presence through the first half of the book. Paxton (and perhaps Burroughs, to some extent) find admirable qualities in this Martian super-surgeon, whose experiments bring benefits along with terrors. But Ras Thavas’s unyielding opposition to “sentiment” (which Paxton astutely observes is itself a sentiment) puts him firmly in the evil mad scientist camp. He’s also one of the most quotable figures in Barsoom, since he loves launching into pompous explanations about the superiority of his rational thinking: “In my world, nothing counts but brain and in that respect, and without egotism, I may say that I acknowledge no superior.” “…were it not for sentiment there would be no fools to support this work that I am doing.” “All men … analyse an individual, and by his predilections and his needs they classify him as friend or foe, leaving to the weak-minded idiots who like to be deceived the drooling drivel of sentiment.” Fun villainy to chew on.

Although The Master Mind of Mars’s religious satire comes nowhere near The Gods of Mars, it does make for some humor and some of the best-written passages in the book. When Paxton arrives in Phundahl, he finds out from his ally Dar Tarus that the nation’s religion is a mix of mysticism and rigid narrow-mindedness that prohibits all knowledge outside of what comes from their god, Tur. Because of this, Paxton finds that Phundahl is “the least advanced civilization of the red nations upon Barsoom.” Paxton seems more amused with this state of affairs than angry or even critical, and indulges in some light satirical comedy:

“There is but one god,” replied Dar Tarus solemnly, “and he is Tur!”

“Was that Tur?” I inquired.

“Silence, man,” whispered Dar Tarus. “They would tear you to pieces were they to hear such heresy.”

“Oh, I beg your pardon,” I exclaimed. “I did not mean to offend. I see now that that is merely one of your idols.”

Dar Tarus clapped a hand over my mouth. “S-s-s-t!” he cautioned to silence. “We do not worship idols — there is but one god and he is Tur!”

“Well, what are these?” I insisted, with a sweep of a hand that embraced the several score images about which were gathered the thousands of worshipers.

“We must not ask,” he assured me. “It is enough that we have faith that all the works of Tur are just and righteous.”

This goes on for a bit — most of a chapter, actually — but I can’t lie: Burroughs with a burr in his sock is always a good time, even when it has nothing to do with the rest of the story.

The brain- and body-swapping gets into a pleasant mess and allows for interesting turns in the plot. By the time the climax closes in, nobody has the right body and Paxton has to pull out complex surgery to get it all straightened out. It feels like a practice run for the insanity of The House of Frankenstein.

The Negatives

I admire the tighter plotting, but The Master Mind of Mars lowers its scale in another, less fortunate way: the action. This is an Edgar Rice Burroughs novel — I want big, bombastic action, dammit! Where are the arena battles with ravening banths? The epic clashes between warring nations? The titanic aerial warfare? The scenes of heroes hacking through innumerable foes? Thuvia, Maid of Mars was slighter than the John Carter trilogy, but never lacked for epic action. The Master Mind of Mars is the least thrilling book in the Barsoom series so far. It isn’t a failure or a bad book, exactly, but it does not live up to the stories that came before it. I’m glad now that I took a break from the series, because if I came at this book directly off of The Chessmen of Mars, I would have assumed that fatigue was making it less exciting. Coming at it fresh made me understand better what wasn’t working.

I admire the tighter plotting, but The Master Mind of Mars lowers its scale in another, less fortunate way: the action. This is an Edgar Rice Burroughs novel — I want big, bombastic action, dammit! Where are the arena battles with ravening banths? The epic clashes between warring nations? The titanic aerial warfare? The scenes of heroes hacking through innumerable foes? Thuvia, Maid of Mars was slighter than the John Carter trilogy, but never lacked for epic action. The Master Mind of Mars is the least thrilling book in the Barsoom series so far. It isn’t a failure or a bad book, exactly, but it does not live up to the stories that came before it. I’m glad now that I took a break from the series, because if I came at this book directly off of The Chessmen of Mars, I would have assumed that fatigue was making it less exciting. Coming at it fresh made me understand better what wasn’t working.

Not only does The Master Mind of Mars never deliver a major action set-piece, it offers almost no action at all until halfway, and there’s not much even after that. Paxton gets involved in a brief fight when he first appears on Mars (with the Red Martian we later get to know as Gor Hajus), and then spends half the book hanging around Ras Thavas’s home learning how to perform surgery. Not until Paxton and his trio of body-misfits try to seize a Phundahl flier in a mid-air fight in Chapter Nine (of Fourteen!) does the action resume. The finale passes by in a slow whimper as Paxton manipulates the court of Phundahl after a tensionless fight with the guards at Ras Thavas’s house. The damsel in distress doesn’t even spend the book in distress: most of the time she’s in suspended animation, hidden away on a shelf so the hero can retrieve her when necessary. I never felt that Valla Dia was in any serious danger.

This low-level adventuring is no better displayed than the use — or lack of it — of the “white-ape man” Hovan Du. This should be a fantastic character, kicking butt in ape shape while having his mind at war with itself between its bestial and human drives. But Hovan Du does almost nothing, either as a battler or as a character. He disappears into the background for most of the time he accompanies Paxton and his other allies. What might a first-person tale from this Hovan Du’s perspective be like? There’s a piece of fanfic I would like to read.

There isn’t much to say about the rest of the supporting cast. Valla Dia appears only briefly before getting literally shelved, Gor Hajus never rises to show off his famous assassin skills, Dar Tarus only seems present to deliver the satire on religious fanaticism, Xaxa gets an unexciting finale, and Sog Or is an afterthought for a subplot that gets mostly discarded. Even Ras Thavas, a great character, ends up vanishing for half of the book and gets a lukewarm send-off not befitting a title character. In the last paragraph, Paxton lists off the classic characters of Barsoom whom he meets in when he reaches Helium, and it’s impossible not to wish that they took the starring roles. At least Woola! (Wait, Paxton doesn’t mention Woola. Why not?)

The religious satire of Tur contains some of the most enjoyable writing of the book, but it also has no connection to the rest of the story. A comparison with The Gods of Mars is instructive. That book used the satirical slant on organized religion as the center of its plot; John Carter aims to destroy the two false cults that have Barsoom in their grip. But the intolerant religion of Tur in The Master Mind of Mars gets tossed in as filler. It doesn’t change the character of Dar Tarus, the mouthpiece for this dogma. After making a few religious threats, he turns back into Paxton’s ally and one of the main heroes, and his dedication to Tur never comes up again.

The only later effect the religion has on the story is that Paxton masquerades as the god using a giant mechanical head. Burroughs was trying to create a balance to the extreme rationalism of Toonol, but that’s not necessary because Toonol creates its own rebuttal: its rational extremity produces a form of the sentimentality it claims to oppose. As a theme for the novel, Toonol is all that’s needed. The religion of Tur feels like ERB freezing the story cold so he can hurl out his opinion on organized religion. By the novel’s end, neither the philosophy of Toonol nor Phundahl have anything to do with the unfolding events.

The only later effect the religion has on the story is that Paxton masquerades as the god using a giant mechanical head. Burroughs was trying to create a balance to the extreme rationalism of Toonol, but that’s not necessary because Toonol creates its own rebuttal: its rational extremity produces a form of the sentimentality it claims to oppose. As a theme for the novel, Toonol is all that’s needed. The religion of Tur feels like ERB freezing the story cold so he can hurl out his opinion on organized religion. By the novel’s end, neither the philosophy of Toonol nor Phundahl have anything to do with the unfolding events.

Paxton’s more realistic portrayal has an unfortunate side as well: he’s sometimes a bit of an idiot. Not at “Carson Napier of Venus” level, but when he allows himself to serve for months to an obvious ice-cold killer who admits he trusts Paxton only because he doesn’t trust Paxton, a reader might long for John Carter to come along and slice and dice the Martian madman on the spot. Carter may be a braggart, but he gets things done. Paxton also fails to take into account that Ras Thavas has close connections to Xaxa and would immediately contact the evil princess to tell her that Paxton is coming for her. But Paxton’s most unforgivably stupid moment is when he negotiates his deal with Ras Thavas on the operating table, and expects Ras Thavas to honor it after Paxton’s bargaining power vanishes. Ras Thavas has admitted that the sole force driving him is self-interest, so why should Paxton think the surgeon won’t seek revenge when Paxton violates his trust?

Burroughs was simply not adept at working plot twists. Hiding that Carthoris was really John Carter’s son was painfully clumsy in The Gods of Mars, and disguising Valla Dia’s true identity is a failure here. What kind of women do the heroes of Barsoom marry? They marry princesses! The moment Valla Dia tells the story about the Princess of Duhor escaping in disguise from her city, readers know exactly what will unfold in the finale. Paxton ought to have figured it out as well, since by his own admission he reads Edgar Rice Burroughs! Even the author seems to have given up on the plot twist, since he trots out the reveal in a pedestrian way in the last page.

Craziest bit of Burroughsian Writing: “All that night we sped beneath the hurtling moons of Mars, as strange a company as was ever foregathered upon any planet, I will swear. Two men, each possessing the body of the other, an old and wicked empress whose fair body belonged to a youthful damsel beloved by another in this company, a great white ape dominated by half the brain of a human being, and I, a creature of a distant planet, with Gor Hajus, the Assassin of Toonol, completed the mad roster.”

Best Moment of Heroic Arrogance: Aside from pretending to be a god from inside the safety of a giant metal head, Paxton isn’t much for the big heroic gestures.

Times a “Princess” (Female Lead) Gets Kidnapped: 1

Best Creature: Unfortunately, no new monsters here.

Most Imaginative Idea: Ras Thavas’s numerous bio-experiments, in particular the half-ape/half-man brain fusing.

The Importance of Word Order on Mars: “On the contrary they said just exactly the opposite from what they said at the other [time]. At that they said, Tur is Tur; while at this they absolutely reversed it and said, Tur is Tur. Do you not see? They turned it right around backwards, which makes a very great difference.”

Should ERB Have Continued the Series? A good question. Paxton doesn’t feel right to star in another book, John Carter is already wrung dry, and changing to a new, third-person narrator is no longer fresh. If ERB can find a topic that excites him, he should plow ahead. But at this point continuing the series just for the sake of continuing the series is a poor idea.

Next: A Fighting Man of Mars

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

One interesting thing (and I wonder if this was conscious on Burroughs’ part): I think this is the first Mars book that really veers in the direction of actual science fiction, what with the brain transplants and all.

“Not until Paxton and his trio of body-misfits try to seize a Phundahl flier in a mid-air fight in Chapter Nine (of Fourteen!) does the action resume.”

I really wanted more of these guys, especially Hovan Du. It seems like there was a lot of great brawling and adventuring that could have come from that crew except that Burroughs left it all on the shelf.

Yes, the crew that Paxton recruits is disappointing in how little they really end up doing. Not much in the way of assassin skills from Gor Hajus. Nothing much made of Dar Tarus’s fanaticism. And Hovan Du’s super-ape status is wasted.

if you want more Burroughs mad scientist fun, there’s always his The Monster Men — a stand-alone work.

I’ll have to try The Monster Men. I loved the Mars series but I like your criticism. He did leave a lot of great material go. I read him when I was young and I gobbled up every bit.

Now that I’m older I do get tired of the princesses getting captured. ERB’s heroes are a bit too superman like. They would probably be better off not being as super. ERB is so wild with his ideas that they sometimes carry the story.

And another thing, having an intelligent brain and an ape body isn’t so bad. Chicks dig it. Hovan Du is the luckiest guy on Mars, trust me.

I’ll take your word for it, Ape. But couldn’t Burroughs have told me about it when he had the chance?

Well, check out King Kong, Mighty Joe Young, or a Ron Perlman flick and you’ll see what I mean. The girls can’t resist the gorilla charm.

I confess, I’m a big fan of Woola and the White Apes. I even had a dog I named Woola after the namesake. He didn’t have as many teeth but he could chew the hell out of anything. He even took out a rain gutter once time. The original Woola would have been proud.

I think Burroughs greatest weakness was the villains. The hero was too heroic and you just knew that when they caught up to the villain there was going to be a pounding. I think that kind of hero was appealing to the pre 60s generation. They liked to see evil pounded flat whereas now I think people like their heroes normal but who take out an overpowering villain.

[…] (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913–14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The Chessmen of Mars (1922), The Master Mind of Mars (1927), A Fighting Man of Mars […]

[…] Edgar-rice-burroughs-mars-part-6-the-master-mind-of Mars […]

[…] (1913), The Warlord of Mars (191314), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The Chessmen of Mars (1922), The Master Mind of Mars (1927), A Fighting Man of Mars (1930), Swords of Mars […]

[…] (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913–14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The Chessmen of Mars (1922), The Master Mind of Mars (1927), A Fighting Man of Mars (1930), Swords of Mars (1934–35), Synthetic Men of Mars (1938), […]