Finding Deliverance in a dearth of heroic fantasy

I lay with the flashlight still in one hand, and tried to shape the day. The river ran through it, but before we got back into the current other things were possible. What I thought about mainly was that I was in a place where none—or almost none—of my daily ways of living my life would work; there was not habit I could call on. Is this freedom? I wondered.

I lay with the flashlight still in one hand, and tried to shape the day. The river ran through it, but before we got back into the current other things were possible. What I thought about mainly was that I was in a place where none—or almost none—of my daily ways of living my life would work; there was not habit I could call on. Is this freedom? I wondered.

–James Dickey, Deliverance

So you’ve read yourself out of Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber, closed the cover on the latest Bernard Cornwell and Joe Abercrombie, and you’re looking for something new in heroic fiction. But you can’t seem to find what you’re looking for. Rather than slumming around in the dregs of the genre or reaching for The Sword of Shannara (with apologies to fans of Terry Brooks), my suggestion is to take a look at modern realistic adventure fiction and non-fiction.

I read heroic fiction for the action, the adventure, the storytelling, and the sense of palpable danger that real life (typically) doesn’t provide. Likewise, I find that works like The Call of the Wild and The Sea Wolf by Jack London, Alive by Piers Paul Read, and Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer satisfy the same primal needs as the stories of an Edgar Rice Burroughs or David Gemmell. The best modern adventure fiction/non-fiction stories are bedfellows with heroic fiction: While they may not contain magic or monstrous beasts, they allow us to experience savagery and survival in the wild and walk the line of life and death.

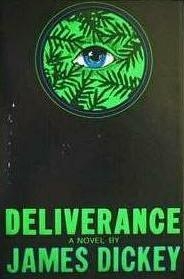

My favorite work in this genre is Deliverance by James Dickey, and it’s to this book that I’d like to devote the remainder of this post.

Dickey’s novel has been very much overshadowed by the 1972 film of the same name, which is admittedly great and quite faithful to the source material (Dickey himself wrote the screenplay and has a small, memorable role in the film as the menacing Sheriff of Aintry). Needless to say I’m a fan.

But like most screenplays, some sacrifices had to be made in the transition from novel to screen. Among the casualties are character development and Dickey’s beautiful prose style. In addition the one graphic scene in the film (if you’ve seen it, you know the one I’m referring to) has become such a punchline that it overshadows the rest of the film and renders nuanced conversation almost impossible. In short, you’re selling yourself short if you’ve watched Deliverance but haven’t read Dickey’s novel.

Deliverance is the story of four men who embark on a three-day canoe trip on the fictional Cahulawassee River in the wilds of Georgia. An encounter with some murderous locals plunges what is at first a relatively benign men’s retreat into a tale of terror, savagery, and survival.

I speak highly enough of the greatness of Deliverance. Time Magazine listed it as one of the 100 best English-language novels from 1923-2005 (ageed). Dwight Garner recently commemorated its 40 year anniversary in a fine article on the New York Times website , highlighting the book’s lean, raw power and ability to unsettle.

Deliverance shares more in common with heroic fantasy than first meets the eye. One of my favorite Leiber stories is 1966 Hugo nominee “Stardock,” in which Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser scale a terrifying, sheer-faced mountain of the same name. Although they fight supernatural creatures, the true antagonist of the story is Stardock itself. Deliverance does “Stardock” one better in a cliff-climbing scene for which I have yet to find a peer. You, the reader, literally feel exhausted when Ed reaches the top.

And Deliverance offers much more than just action. It confronts its reader with some heavy philosophical questions. For example, the meaning of the title: Are the four men being delivered from their mundane, suburban existence into the calm, cold clarity of doing “the one thing, the only thing for a man to do” (to steal a line from Hemingway) when confronted with naked survival? In other words, is the trip an awakening from the slumber of modern existence into “real life?” Or is their deliverance a miraculous return out of danger and into the realization that the same family and home that can sometimes seem to drag us down like a drowning man are a priceless gift, and that nature is no idyllic retreat but an active menace, steeped in fang and claw? Dickey’s book offers both possibilities and does what all great works of literature do: It makes us think.

Lewis (played by Burt Reynolds in the film) is a fascinating character. At first he’s set up like the iconic hero in the mold of Robert E. Howard’s Conan: A muscular survivalist, a great shot with his bow, and an anti-establishment iconoclast. But after badly breaking his leg in the rapids of the Cahulawassee he’s effectively emasculated (something we don’t expect in heroic fiction), and his and the rest of the group’s survival is placed into the soft hands of Ed Gentry. An art director in a consulting firm whose biggest challenges are ennui and the occasional demanding client, Gentry finds himself faced with the stark decisions necessary of survival, including killing another man in order to live. The bare essentials of this choice sharpens Ed’s mind into a higher and tighter focus, and puts him in transcendent touch with the pulsing throb of life.

Howard’s themes course beneath Dickey’s novel like the strong, steady flow of the Cahulawassee. In “Beyond the Black River” a calloused-hand forester ends the tale with an iconic line Howard himself believed deeply: “Barbarism is the natural state of mankind. Civilization is unnatural. It is a whim of circumstance. And barbarism must always ultimately triumph.” Deliverance reaffirms this dictum. Lewis correctly advises against bringing the body of a dead mountain man to the local police: He knows there’s no way four city men are going to get a fair trial in a town where everyone is related. They must rely on their own fortitude and naked will to survive.

Go into the woods deep enough, get into it deep enough, and law and civilization melt away, even here on earth, in these times. Just like a Barsoom or Melniboné, the deep woods of Dickey’s Deliverance take us to places and situations we’d never want to confront in our own lives, but can savor vicariously in the pages of a book.