David Gemmell: An Appreciation

An Heroic Career in Heroic Fantasy

By Wayne MacLaurin & Steve Tompkins

Copyright 2006 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

We come not to bury David Gemmell — that was the sorrowful duty of his family and friends after his death on July 28, 2006 — but to praise him and a contribution to recent heroic fantasy that was profound as well as prolific.

We come not to bury David Gemmell — that was the sorrowful duty of his family and friends after his death on July 28, 2006 — but to praise him and a contribution to recent heroic fantasy that was profound as well as prolific.

Sword-and-sorcery has always been as associationally damned by mediocre or mercenary writers as by those who automatically dismiss the subgenre. From the near-immaculate conception of “The Shadow Kingdom” in 1929 on up through even the boom years of the late ’60s to the mid-’80s, there has quite simply never been as much of the really primo, adventurous and non-counterfeit stuff as we would like. With 30 novels in 22 years, Gemmell did more to change that than anyone save possibly Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber.

Our tribute begins with a personal reminiscence by Wayne MacLaurin, and includes an overview by Wayne and Steve Tompkins of what is now Gemmell’s legacy: all those novels.

Much of my teenage and early-adult years were spent browsing the shelves of The House of Speculative Fiction, a small local fantasy and science-fiction book store that used to grace an old downtown house here in Ottawa, Canada. The selection was astounding and I’m pretty sure I simply traded the paychecks from my part-time jobs for a weekly pile of new recommendations from owners Pat and Rodger. It was there that I first discovered the yellow bound DAW mass market editions of Michael Moorcock and Tanith Lee with their wonderful Michael Whelan covers, and it was there that I was introduced to some of my favorite authors, including Feist, Eddings, Powers and Simmons. Being in Canada, the House of Speculative Fiction had another advantage: bringing in a wide assortment of British authors whose works were mostly strangers to North American shores.

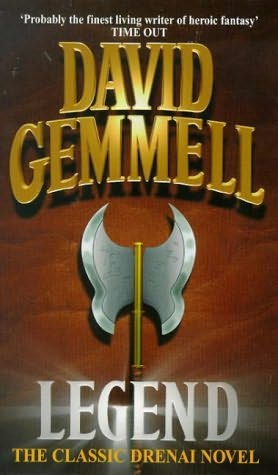

In 1984, around the time Ottawa hosted the World Fantasy Convention, one of the books I brought home was David Gemmell’s Legend.

Legend, the title of Gemmell’s first novel, also describes the stature the book has aquired. The fortress of Dros Delnoch, a dream of impregnability, defies 500,000 Nadir tribesmen, a nightmare of irresistible momentum directed by Ulric, the Warlord of the North. The premise is straightforward enough, but stunning as depicted by Gemmell. British authors often force their heroes to work harder, while exposing flaws and even failing. Need we say that this makes such characters more rather than less heroic?

Legend, the title of Gemmell’s first novel, also describes the stature the book has aquired. The fortress of Dros Delnoch, a dream of impregnability, defies 500,000 Nadir tribesmen, a nightmare of irresistible momentum directed by Ulric, the Warlord of the North. The premise is straightforward enough, but stunning as depicted by Gemmell. British authors often force their heroes to work harder, while exposing flaws and even failing. Need we say that this makes such characters more rather than less heroic?

In Legend, Druss comes down from his retirement “among the pine and the snow leopards,” having been on the most intimate of terms with Death for decades. He fears senility or inexorable infirmity far more than dying in the very teeth of the Nadir, a fact he demonstrates again and again as the siege moves inward with the fall of Dros Delnoch’s concentric walls to the Nadir one by one. The loss of each is an epic of endurance sluiced away by life-expenditure.

To insist upon the mortality of protagonists is to risk much in an industry where your next book’s success often springs from how well the last book did and where recurring characters are as important to the fans as the books themselves. Those with a taste for publishing trivia might be interested to learn that Gemmell’s first U.S. editions were handled by New Infinities; a company owned by none other than Gary Gygax of Dungeons & Dragons fame. Unfortunately, with botched cover art, spotty marketing and poor distribution, this was not exactly the most successful of British Invasions. It was not until the mid-’90s that Gemmell began to claim his rightful shelf-space in American bookstores.

In The King Beyond the Gate (1985), a century has passed since Legend. This Drenai novel is a rarity in that the people of that western nation, usually a stone in the shoe of a neighboring god-emperor or continent-conqueror, have turned on themselves. The general Ceska has “built an empire of terror” but errs in deciding to wipe out the elite unit in which Tenaka, the Khan of Shadows, serves. “A product of war, a flesh and blood symbol of uneasy peace,” Tenaka is a descendant of both Ulric and the Drenai paladin the Earl of Bronze. He and other outcasts such as Pagan, a king far from the Zulu-esque tribe he rules beyond the Mountains of the Moon, and the disfigured arena veteran Ananais Darkmask defy Ceska’s man-beast Joinings and the Dark Templars. In one of the touches that enhance the Drenai novels, one scene is set in a chamber where “the pained mosaic showing the white-bearded Druss the Legend had peeled away in ugly patches.”

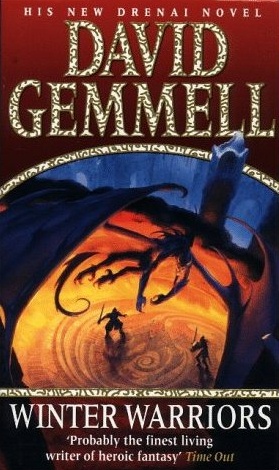

Quest for Lost Heroes (1990) and Winter Warriors (1996) occur during different, and Druss-lacking, dark hours in Drenai history, and assemble Seven Samurai/Magnificent Seven-style teams of lethal specialists and pariahs. In the latter novel, under their warrior-king Skanda, an Alexander with all of the Macedonian’s hubris but less of his genius, the Drenai are overextended and understrength in a campaign that has carried them deep into the eastern empires. One character concludes that “The universe is in a state of constant war. … If that is true, then Chaos commands the most cavalry,” and soon suitably chaotic events loose the Windborn, ancient demons who long to “taste the sweet joys that spring from human fear.”

Of Druss we can surely say, by this axeman Gemmell rules. The First Chronicles of Druss the Legend (1993) surmounts the clunkiest of his titles to be one of his best books. Druss returns, or more accurately pre-returns, to pursue all those who abduct or later sell his bride Rowena across the world, and is in turn pursued by the demonic destiny that once swallowed his grandather Bardan’s very being. A year’s hopeless, lightless confinement during which he is as gnawed by rats as by hunger.

The Legend of Deathwalker (1996) is an origin story of sorts for the all-conquering Nadir, with whom Druss will be reunited on the battlements of Dros Delnoch.

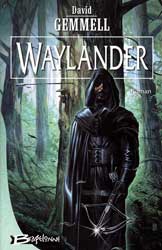

Waylander the Slayer, Gemmell’s other recurring Drenai protagonist, debuted in Waylander (1986). With his own previous success as an assassin pursuing him with hellhound relentlessness, this recalcitrant hero is forced into a quest for the Armor of Bronze, all that can save the kingdom whose monarch he himself has murdered.

Waylander the Slayer, Gemmell’s other recurring Drenai protagonist, debuted in Waylander (1986). With his own previous success as an assassin pursuing him with hellhound relentlessness, this recalcitrant hero is forced into a quest for the Armor of Bronze, all that can save the kingdom whose monarch he himself has murdered.

That same sable-and-crimson past tracks and corners Waylander in each of the futures he has devised for himself in Waylander II: In the Realm of the Wolf (1992) and Hero in the Shadows (2000). In the first of the two follow-ups, the bounty offered by the Lord Protector of Drenan for Waylander’s head forces him to begin fashioning his adopted daughter Miriel in his own deadly image. In the second, rivalries between the ruling families of Kydor, the far-off realm where he has reinvented himself as a landowner and merchant prince, are mere fripperies when contrasted with a conspiracy to bring about the return of Anharat the Demon Lord. As did Karl Edward Wagner with the Final Guard in his 1979 Conan pastiche The Road of Kings, Gemmell conscripts the terracotta soldiery of Xi’an, China for his own imaginative purposes in this novel, which also tells of how the first glorious human civilization of Kuan Hador took “one little step at a time toward the dark.” The story of Druss begins with his end in Legend; the story of Waylander ends with his beginning, in that his exertions against inhuman forces earn him a chance to revisit the tragic events that made him a peerless assassin and a hopeless human being.

White Wolf (2003) reportedly displeased Michael Moorcock, as did Stormrider, with its use of titles that Moorcock regarded as “preowned”; the creator of Elric has not exactly been an Eternal Champion of Gemmell’s heroic fantasy. Here Skilgannon the Damned, a sometime generalissimo for the Witch-Queen, shares center stage with Druss. Much as Robert E. Howard did with Kull of Valusia in “Kings of the Night,” The Swords of Night and Day (2004) yanks both Skilgannon and Druss forward in time to an era in desperate need of their defining refusal to admit defeat.

In Ghost King and Last Sword of Power (both 1988), Gemmell audaciously writes Arthur/Artorius out of the fall of Roman Britain and its aftermath in order to tell a darker tale of Uther Pendragon. As the never-defeated Blood King, Uther is the scourge of the Saxons, Angles and Jutes, but now “The grim, grey god walks among men.” The North has emptied to swell the horde of Goths led by the man-god Wotan, who launches his longships across the bodies of sacrificed maidens.

The tension between the amoral inclinations of many Gemmell characters and the roles that fate (always a fell sergeant swift in his arrest) conscripts them to play is nowhere better dramatized than in Jarek Mace, the half-Robin Hood, half-William Wallace figure who balks at being the hero of Morningstar (1992). The novel’s setting is the first of Gemmell’s crypto-Britains, a large island the north of which belongs to “Highland tribes, mostly of Pictish and Belgaic origin.” The Highlanders are now menaced by the Angostins, who even more than their Norman inspiration excel “only in battle and in the building of monstrous fortresses of grey stone.” Even as the Angostin “Edmund, the Hammer of the Highlands,” prepares to drench the north in the blood of its inhabitants, the reawakened evil of Golgoleth and his fellow Vampyre Kings portends a different plan for that same bodily fluid.

Gemmell never met a temporal or interdimensional portal he didn’t long to explore, as evidenced by Ironhand’s Daughter (1995), in which the imperial-minded Outlanders have crushed the highland clans at Colden Moor. Their last best hope takes the unlikely, free-spirited form of Sigarni, who discovers her destiny in as brutal a fashion as Gemmell has ever committed to paper. The Hawk Eternal, also from 1995, celebrates the clansmen’s exuberance and lack of regimentation against an earlier foe, the Aenir, who look for weaknesses through ice-blue eyes, sneer through their yellow beards and swear by Vatan: “The way of the Grey God was the way of the Aenir, and no one questioned either.” The great hall from which they will launch their conquest of the highlands is Aesgard and their warlord is Asbidag, “the destroyer of nations, the bringer of blood.” Gemmell’s maverick mountain-rover Caswallon kills many of them, and wounds more with his insight into their roiling psyches: “Like all killers, you fear that a greater killer will stalk you as you stalk others. You cannot exist with a free people outside your borders.” Even better, possibly the best putdown of the Fascist mentality since Hemingway’s “a lie told by bullies,” are the words of a lone dying highlander: “You miserable whoresons… warriors? You’re like a flock of sheep with fangs.”

In Sword in the Storm (1998) and 1999 Midnight Falcon (1999), the first two novels in his Rigante series, Gemmell telescopes and Rotoscopes history to create a pre-Arthurian Matter of Britain. Even as Connavar the Demonblade, a Turlogh O’Brien-like killer bearing Bran Mak Morn’s burdens, strives to muster the Keltoi tribes of his island against the ever-annexationist legions of Stone poised to cross from the mainland, he must first deal with an invasion from the north: Vars sea wolves in longships from “the fjord country,” led by Shard son of Arald; it is probably redundant to reveal that the Vars sacrifice their captives to Wotan.

In Sword in the Storm (1998) and 1999 Midnight Falcon (1999), the first two novels in his Rigante series, Gemmell telescopes and Rotoscopes history to create a pre-Arthurian Matter of Britain. Even as Connavar the Demonblade, a Turlogh O’Brien-like killer bearing Bran Mak Morn’s burdens, strives to muster the Keltoi tribes of his island against the ever-annexationist legions of Stone poised to cross from the mainland, he must first deal with an invasion from the north: Vars sea wolves in longships from “the fjord country,” led by Shard son of Arald; it is probably redundant to reveal that the Vars sacrifice their captives to Wotan.

Both Sword in the Storm and its sequel are haunted by the Morrigu, “the Seidh goddess of mischief and death,” who appears at crucial moments in the life of Connavar. He becomes “Laird, and then War Chief, and finally the first High King in hundreds of years,” all while never losing sight of the menace of Stone and its Caesar-suggesting commander Jasaray. Stone the victory of fact over fancy, the death of both the natural and the supernatural, leaving only the unnatural, is one of Gemmell’s most powerful creations in more ways than one, as Connavar can attest from his dreams: “I saw Jasaray in many guises, on many worlds. He won every battle he fought. I saw visions of horror beyond belief, of worlds dying, the air poisoned by towers belching poisons into the air, of dead trees, their leaves scorched, and fertile lands turned into deserts. I saw men with grey faces and frightened eyes, living in cities of stone, scurrying like ants from day to day.”

In one of Edward Gibbon’s most celebrated passages he tells how “the masters of the fairest and most wealthy climate of the globe turned with contempt from gloomy hills assailed by the winter tempest, from lakes concealed in a blue mist and from cold and lonely heaths, over which the deer of the forest were chased by a troop of naked barbarians.” The men of Stone do not turn away but are turned away by the sanguinary end of Midnight Falcon. The next Rigante novel, 2000’s Ravenheart, jumps many centuries ahead to a fantasticated version of the Highland clearances we know from Scottish history. Amusingly, Gemmell includes a passing reference to the “Essays on War of the Emperor Jasaray. There is little nobility there, merely a vaunting ambition to conquer as much of the known world as possible.” We learn in Ravenheart and Stormrider that the true victors of the wars between the Keltoi and Stone turned out to be the Vars, who have evolved — in some ways — into the Varlish, lords of the south, one of whom admits “The Keltoi were a proud warrior race. It does not suit us that they should remain so. So we denigrate their culture, and what we cannot denigrate we suppress.” Wearing the pale blue and green Rigante plaid is “an act punishable by death,” as is daring to claim that Connavar and Bane were Rigante heroes. Naturally, new heroic leaders are created in the clashes between the high-handed and the highlanders.

Wolf in Shadow (1987) is a post-apocalyptic novel set 300 years after the world was toppled on its axis. Every scene demonstrates Gemmell’s love of classic American Westerns (in a bragging match with friendly sales-rival Terry Pratchett, he once revealed that he’d purchased a rifle owned by Wyatt Earp) as humanity is isolated and victimized by brigands and warlords. Jon Shannow is a “lonely, tortured man on a quest with no ending, riding through a world of savagery and barbarism,” and, fortunately for his sake and that of the few remaining innocents, a matchless gunfighter. However, Abaddon, Lord of the Pit, dominates the wastelands with his army of Hellborn. The Last Guardian (1989) has Jon Shannow seeking to find the Sword of God and close a gateway that yawns between past and present. By the time of Bloodstone (1994), the Deacon and his Jerusalem Riders mock Shannow’s ideals with their murderous theocracy, and an insatiable extradimensional evil seizes an opportunity to capitalize on the prevailing perversion of righteousness.

Outstanding among Gemmell’s standalones is his 1989 novel Knights of Dark Renown, the borrowed title of which is a tip of the helm to Graham Shelby’s 1969 novel about that unholiest of Crusaders Reynald of Chatillon, The Red Wolf of Palestine. We do not know for a fact that Gemmell was ever required to sit through Richard Wagner’s Parsifal on a bad date, but his Knights of the Gabala, “grander than princes, more than men,” are Parsifalian paragons of pure pride and proud purity. The novel’s nomenclature — a Fomorian War, a city of Furbolg, Manannan, a disgraced knight — might be readable as Gemmell’s resentment of the degree to which Wagner Teutonified the original Celtic legends, while “Gabala” has the requisite “G” for “Grail” but also puts us in mind of the Kabbala. Ahak, ruler of the Nine Duchies, is hellbent on the “removal” of all nomads and aliens: “Our strength, both physical and spirtual, has been polluted… When the realm is rid of all impurity, we shall rise again and become pre-eminent among nations!”

Outstanding among Gemmell’s standalones is his 1989 novel Knights of Dark Renown, the borrowed title of which is a tip of the helm to Graham Shelby’s 1969 novel about that unholiest of Crusaders Reynald of Chatillon, The Red Wolf of Palestine. We do not know for a fact that Gemmell was ever required to sit through Richard Wagner’s Parsifal on a bad date, but his Knights of the Gabala, “grander than princes, more than men,” are Parsifalian paragons of pure pride and proud purity. The novel’s nomenclature — a Fomorian War, a city of Furbolg, Manannan, a disgraced knight — might be readable as Gemmell’s resentment of the degree to which Wagner Teutonified the original Celtic legends, while “Gabala” has the requisite “G” for “Grail” but also puts us in mind of the Kabbala. Ahak, ruler of the Nine Duchies, is hellbent on the “removal” of all nomads and aliens: “Our strength, both physical and spirtual, has been polluted… When the realm is rid of all impurity, we shall rise again and become pre-eminent among nations!”

The good riddance to bad racial rubbish will come courtesy of the Gabala Knights, who years before rode into Vyre “as if into Hell itself to destroy the essence of evil.” There the Knights had been welcomed with open arms to a “white many-towered city,” the celestial whiteness of which can only be diabolical. Sure enough, rest and recreation result in the re-creation of the Knights as leech-lords sustained by Hambria, an elixir vitae prepared from the blood of racial inferiors. They return to the Nine Duchies to enact Ahak’s purification program through vampirism; and their invincible Lord Commander Samildanach is among Gemmell’s most charismatic villains: “His hair was close-cropped and white, his eyes a brilliant blue.” There is little in Knights of Dark Renown that is not brilliant.

For Dark Moon (1996), Gemmell invents the Renaissance-ian backdrop of the Four Duchies, upon which war fell seven years earlier “like a sentient hurricane,” comple with “eyes of death, cloak of plague, mouth of famine, and hands of dark despair.” Tarantio is too good-hearted to succeeed as the killer the times demand, but he contains within him an alternate personality: Dace, a consummate duellist and leonine predator in tenuously human form. Dace and another compelling Gemmellian collection of misfits will be desperately needed, for a war looms beside which the inter-Duchy conflict is but a playground squabble. The giant Daroth, who “destroy not only races, but also the souls of the lands they inhabit,” are advancing and proving to be somewhat less stoppable than a host of juggernauts. These creatures, who could eat Tolkien’s orcs and Poul Anderson’s trolls for pre-breakfast snacks, are among Gemmell’s most cruelly charismatic creations.

For Dark Moon (1996), Gemmell invents the Renaissance-ian backdrop of the Four Duchies, upon which war fell seven years earlier “like a sentient hurricane,” comple with “eyes of death, cloak of plague, mouth of famine, and hands of dark despair.” Tarantio is too good-hearted to succeeed as the killer the times demand, but he contains within him an alternate personality: Dace, a consummate duellist and leonine predator in tenuously human form. Dace and another compelling Gemmellian collection of misfits will be desperately needed, for a war looms beside which the inter-Duchy conflict is but a playground squabble. The giant Daroth, who “destroy not only races, but also the souls of the lands they inhabit,” are advancing and proving to be somewhat less stoppable than a host of juggernauts. These creatures, who could eat Tolkien’s orcs and Poul Anderson’s trolls for pre-breakfast snacks, are among Gemmell’s most cruelly charismatic creations.

Echoes of the Great Song (1997) blindsided some hardcore Gemmell fans who would have preferred another Drenai novel and were irritated by the whir and hum of the super-scientific machinery seemingly borrowed from sword-and-planet and space opera. Gemmell asks us to imagine how dangerous as well as endangered a Thousand-Year-Reich that has passed its thousandth year might be; the Avatar Empire has been swept away by tsunamis and earthquakes, its power sources preserved but prison-bound by a new Ice Age. There are pitifully few of the ruling Avatars left, which makes them all the more pitiless: “We are a race under siege. We live with the constant threat of extinction.” The hegemony of their surviving shore colonies in the far North is secured only by the calculated terrorization of the local tribes they deride as Mud People. At times the blue-haired, pale-eyed Avatars suggest Wells’ Eloi gone mad and Morlock-icidal; their terrible swift sword is Viruk, a “slim young killer” to gladden the heartlessness of Reinhard Heydrich: “The tribes bred like lice and if Viruk had his way he would bring an army down on them, wiping them from the face of the earth.”

Echoes does not stint on the expected Gemellian blood and thunder, including an apocalyptic Charge of the Light Brigade with energy weapons, but it also is a study of how those who rule by fear are themselves ruled by the fear that those they rule will never fear them enough. As he was able to do repeatedly during his career, Gemmell here devised a fantasy which extradites us to the actuality from which we might prefer to flee: “The world is created for tyrants,” one of the clear-sighted Echoes characters concludes. “It always has been. When the Avatars fall, the most ruthless of the tribes will succeed.

Recalling the Alexander Romances that spread and grew as elaborately patterned as any carpet or tapestry in the eastern realms the warrior-king rode through, Lion of Macedon (1990) and Dark Prince (1991) give a fantastical account of the events preceding Alexander’s birth and the friendship between Parmenion the strategist and Philip the king that spelt doom for Greek independence, before detailing a struggle for the young prince’s soul that rages across more than one reality.

With Troy: Lord of the Silver Bow (2005) and Troy: Shield of Thunder (2006), Gemmell courted comparisons with arguably the greatest, and grimmest, heroic fantasist of all, Homer. The siege of Dros Delnoch was the Englishman’s invention, but the siege and final fate of Troy, its bronze and blood and fire, have been the common inheritance of the Western world for 3,000 years. Gemmell’s Troy is no de-mythicized down-market Schliemann-correcting settlement, but the most lavishly imagined and vividly realized city ever to feature in one of his novels, a cosmopolitan center of Bronze Age multiculturalism and burgeoning prosperity. As such, it is of course doomed, having attracted the predatory attention of an Agamemnon so detestable that his queen Clytemnestra can’t “welcome” him home fast enough.

Gemmell’s Achilles is almost as scary as Homer’s (although he is harshly and gratifyingly schooled by Hektor in a preliminary encounter in Shield of Thunder), while his Odysseus is quite simply unforgettable, once a Sacker of Cities but now a master of the Golden Lie, a compulsive storyteller (“For the story to make men shiver there needs to be a mystical element”), and as such perhaps a stand-in for Gemmell himself.

Fortunately, Gemmell completed 70,000 words of the climactic novel in the Trojan sequence, The Fall of Kings, and his wife/research assistant/test reader Stella will work from the notes he left to finish the book.

“What a complex creature is Man,” a sinister old woman remarks in The First Chronicles of Druss the Legend. Familiar with colorful and criminal characters as both a Londoner and a journalist, Gemmell never failed to capture that complexity, proving again and again that shades of gray can be more dazzling than any amazing Technicolor dreamcoat. Physical confrontations always cast long emotional shadows, and his various worlds permit even his champions no final victories; peace is merely a pause or lull between wars. Although as we have seen Gemmell followed Howard in casting his “Norse” characters as agents of atrocity and apocalyptic destruction the better to highlight the resistance and resilience of his “Celtic” characters, perhaps we can still say that our loss is a gain for the Valhalla of heroic fantasists, for in the great hall where Odin’s chosen warriors feast and drink while awaiting Ragnarok, a teller of tales has found himself a new audience. But they will not, cannot be more appreciative than those of us who have read Gemmell here on Midgard.

3 thoughts on “David Gemmell: An Appreciation”