Fiction Review: Salon Fantastique: Fifteen Original Tales of Fantasy

A Review by Mark Rigney

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

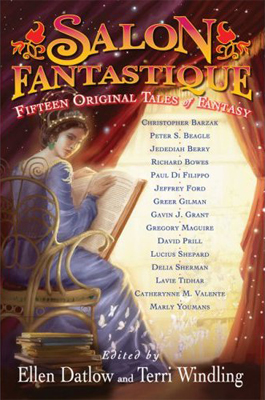

Salon Fantastique: Fifteen Original Tales of Fantasy

Edited By Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling

Thunder’s Mouth Press (396 pages, September 2006, $16.95)

The central conceit in this latest collection of shorts from editors Datlow and Windling is the reinvention of the tried-and-tested but now essentially defunct idea of the literary salon. In days gone by the salon would have been contained by the confines of a room, but now, given the infinite “room” of cyberspace, salons (such as they are) often exist worldwide, instantly and constantly. Within this tome’s crammed pages the reader will find a less interactive salon, but a solid grouping of talent nonetheless. Most of the authors included have a strong publishing history; no lightweights or newcomers here. Were one to enter the Algonquin Club and find this coterie of fantasy’s finest sitting down to lunch, one imagines the conversation would be both delightful and lively.

Delia Sherman leads off with “La Fée Verte,” a historical piece, quite long, featuring Victorine, a woman of ill repute who rises despite all toward the heights of Parisian society, while all around her war and revolution simmer and boil. Her unquenchable selfishness makes her a difficult heroine to root for, but Sherman’s skillful prose and the mysteries surrounding Victorine’s sometime muse, the fortune-telling La Fée Verte, carry the day. The author’s notes explain that Sherman is working on a novel featuring La Fée Verte, and this comes as no surprise; while the story certainly stands on its own merits, it does have the feel of an ardent, careful prologue.

Other highlights spring from the pens of Lucius Shepard, Jeffrey Ford, and Gregory Maguire. Shepard’s “The Lepidopterist” closes the book, and it’s among the few entries set outside of an English-speaking nation. The aged and steadily-drinking Honduran who narrates the tale breaks out of the story just often enough to remind the reader that we are in the clutches of both tale and tale-spinner, but Shepard never digresses for so long that we lose focus or interest. Shepard even finds space for the man’s tics and tendencies — a mild obsession with duppies, for example — without sacrificing the main thrust of the story, the eerie butterfly hatchlings raised by the title’s massively deluded lepidopterist.

Jeffrey Ford offers a more straightforward story with “The Night Whiskey,” in which a small and isolated town’s annual festival takes a bizarre left turn after one member of the community goes well beyond merely communing with the dead. Ford deftly economizes the horror he has to dish out by describing in humorous detail the recovering townsfolk who’ve sampled the mysterious “night whiskey”; these poor souls crawl up into trees, pass out, and have to be fetched down, literally, by hook or by crook. For a time, one could be lulled into thinking the author intends to deliver a peaceful country yarn, but that wouldn’t be Jeffrey Ford. When the villager’s elixir finally delivers its beyond-the-grave cargo, the results are vivid, morally alarming, and stick in the craw long after the telling is done. If all horror stories could manage that little triumvirate, imagine how its readership would grow.

As Gregory Maguire continues to conquer the stage with Wicked, it’s worth remembering he’s also a fine prose-writer. “Nottamun Town” transcends its initial premise — a dying soldier has hallucinogenic visions — by shackling the telling to the traditional riddle song of the title. (For a haunting audio experience, check out Fairport Convention’s nineteen sixty-nine recording of “Nottamun Town,” with the incomparable Sandy Denny on lead vocals.) Having found a scheme to hold the piece together, Maguire teases order from chaos and emotion from “mere” words. Any writer will tell you how easy it is to dip into dream-mode, to spill words like pebbles in a flood, but to hold that flood together and fish from the torrent a story worth the telling — well that, as they say, is another story entirely.

Not all the tales here are set in urban or modern times, but none reside in the lands of Faerie or sword-infested Middle Earths. Paul Di Filippo explores what solutions highly imaginative children might offer in a FEMA encampment after a major tsunami, while Peter S. Beagle tackles an aging soothsayer’s take on a marine entity that uses human minds as an offhand funhouse ride. Greer Gilman, in what is by far the most stylistic entry in the Salon, offers up “Down the Wall,” a whirlwind of avian imagery and incisive sentence fragments. It’s demanding work, the equivalent of Tom Stoppard in the mode, perhaps, of Jumpers, replete with sentences like, “In and out, untiring as wire, they weave a thorny hedge of selves, and in their eddering, enlace their eggs, their moonish precious eggs.”

The other truly adventurous piece comes courtesy of Lavie Tidhar, whose “My Travels With Al-Qaeda” functions like a malarial fever-dream where time slips into sidelong loops and repetitions, and the lead characters are never wholly exonerated of being terrorists themselves.

A few of the stories herein conjure situations that would surely be noticed by the wider world and yet, for reasons that have everything to do with the limitations of the short story form and nothing whatsoever to do with believability, never do. More than one of Salon‘s slipstream events would, in “reality,” resonate far beyond a given story’s hermetic world. Too picky? Hardly. It is in no way unreasonable to ask that a writer follow through on the implications of his or her creation, and readers have every right to hold authors accountable to the interior, self-generated logic of their world-building.

Other authors include Christopher Barzak, Jedediah Berry, Richard Bowes, Gavin J. Grant, David Prill, Catherynne M. Valente and Marly Youmans. For fans of the fabulous in short fiction, the cover price of $16.95 should be seen as a bargain.