Short Fiction Reviews: Subterranean and Apex

A Look at Current Sci-fi and Fantasy Magazines

By David Soyka

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

As defined by the Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy, horror is “the creation and exploration of the emotion of fear or dread” (p. 392). According to Wikipedia, it’s anything “intended to scare, unsettle or horrify” with the element of “the intrusion of an evil…supernatural element…Some modern practitioners of the genre use vivid depictions of extreme violence or shock to entertain their audiences.”

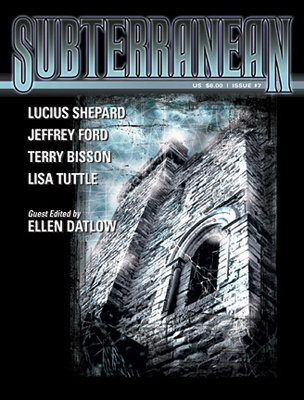

You get a little bit of both perspectives in Issue 10 of Apex, edited Jason B. Sizemore, and Subterranean #7, guest edited by Ellen Datlow. Overall, Sizemore favors those extreme depictions, while Datlow’s selections tend to unsettle us, even, in some cases, without relying on supernatural influences. Life is scary enough as it is.

Datlow says her only criteria was to solicit “anything you want” from writers she sought to work with, and the result is “a mix of urban angst and horror, a story that begins creepily because you know that something bad has got to happen, somewhere along way turning into a sort of love story, a tale about a really disgusting culinary practice of historical France, a lushly written story of contemporary malaise and revenge, another of possibly supernatural guardianship, an intricate, convoluted darkish fantasy about love, and a couple of stories that could have been ripped from the headlines…”

Sounds good to me.

Lisa Tuttle starts off with “Old Mr. Boudreaux,” in which a fiftyish expatriate returns to Houston to attend to her dying mother and take possession of the family homestead. Her mother’s last request is to take care of Mr. Boudreaux, which is a bit odd given that her grandmother’s companion and possible lover would have died years ago. So you know where this is going. The narrator explores the abandoned house, revisits her childhood, finds…well, you know. The predictable plotline notwithstanding, what makes the story work is the emotional wallop, particularly for readers (like yours truly) who have recently lost a parent in a family that wasn’t particularly close-knit, and find out that some odds things were going on that you were oblivious to both as kid and an adult. Perhaps maybe you can go home again, even when both you and home are no longer the same. This and the evocative “nostalgia” more than compensates for the hurried and not particularly original denouement.

One of the most horrific stories here, in the sense of the horror of self-discovery, has just a hint of supernatural elements. In “The King of the Big Night Hours” by Richard Bowes, the protagonist is a university librarian where a student commits suicide by leaping from a balcony at the top of the library’s 12-story atrium. A second suicide follows soon thereafter, before the university acts to put sufficient barricades to prevent yet another repeat performance.

Thirty years ago, the narrator had contemplated a similar action in the very same spot, but was stopped by a West Indian building security officer. Oddly, the narrator is thinking about his rescuer at the very time of the suicide:

At the moment the first kid jumped off a library balcony I was on the phone in my office. In what I eventually saw as more uncanny than coincidental, my friend Alex and I were trying to remember the last time either of us had seen the guy who called himself The King of the Big Night Hours.

(p. 13)

The King not only saves the narrator’s life, but helps him discover his sexual identity. Years go by, AIDS takes claim to the very people who had used their sexuality to celebrate life, and the King is a casualty. The narrator has had no reason to think of him until he is confronted with the reality of the senseless death of young people. At first, he fails to realize how he has learned to repay the kindness given to him so many years ago, and how, if even in a little way, he can affect not only the lives of others, but his own. I realize it’s kind of a backhanded compliment that a story such as this could easily appear in a legitimate “literary” magazine, and while it’s tiresome to keep making these distinctions, it is nonetheless true.

Coincidentally, Paul, the protagonist of “City of Night” by Joel Lane and John Pelan, is also homosexual, though it isn’t as key as it is in the Bowes tale. Paul (who will become an apostle of sorts like his namesake) somehow passes into another reality where insect-like creatures have taken over a ruined cityscape; what few humans survive get by on pills that the creatures provide. Why Paul would willingly return to this bleak reality, no matter how squalid his own existence in the “real” world, is perhaps a metaphor for the lifestyle of drugged self-destruction. Or, maybe it’s just a cool sort of story about depravity. Cross-file under H. P. Lovecraft and Kafka.

I didn’t get Anna Tambour’s “The Jeweller of Second-Hand Roe.” Well, I did get the notion of sacrifice to achieve a greater good, which provides for a powerful denouement. What I didn’t get was why it had to be set in a nineteenth-century world where the family here is in the peculiar trade of selling previously eaten food. Kind of weird, even stomach turning, but I’m not sure exactly what the point was beyond, as an author’s note puts it, “to be gratuitously disgusting.”

I similarly didn’t get “Pirates of the Somali Coast” by Terry Bisson, a series of emails from a child whose cruise ship is taken over the pirates. We’re not talking Johnny Depp kind of pirates, but real cutthroats, though the child doesn’t make that distinction. A lot of blood is shed, and while the point is probably about how children have become desensitized to violence through media depictions, even at three pages it struck me as too long to hold my interest.

The “Holiday” in M. Ricker’s contribution is a little girl who appears to someone who may be a child molester. Is the girl “real,” or a manifestation of the narrator’s perversion. All the more horrific because it may be hitting close to the truth of what goes on in a molester’s head.

Jeffrey Ford’s “Under the Bottom of the Link” is another one of his “wink-wink” post-modernist fables in which the author of the story shows his cards as he presents a series of improbable events that get neatly tied up at the end. The result is, “Look, kiddies, this is how a fairy tale gets told.” Lately, I’ve been reading a lot of these kind of things, which might explain my reaction to this as, simply, “O, another one of those.” I’m ordinarily a fan of Ford’s, and while this has its amusing moments, there are just so many times that a magician can show you what’s up his sleeves before you start wondering whether a change of clothes might be in order.

Similarly, in Apex, Lavie Tidhar’s character in “Daydreams” is reading about Raphael, a dreamer in the employ of the government in a world where “dreams are out of control” and must be managed; or the character may be Raphael himself, or maybe he is dreaming that he is. What if everything turns out to be dream. Are we, indeed, the stuff that dreams are made of, or do we stuff our dreams with what we’d like to be made of? On the other hand, maybe this is all a metaphor about storytelling, and how stories have changed, maybe for the worst, as the mode of telling moved from verbal to paper to screen-based. Maybe, because it’s kind of hard to tell. Which, of course, when you are considering what is “real,” particularly in the non-real mode of storytelling, is the point. I think.

Similarly, in Apex, Lavie Tidhar’s character in “Daydreams” is reading about Raphael, a dreamer in the employ of the government in a world where “dreams are out of control” and must be managed; or the character may be Raphael himself, or maybe he is dreaming that he is. What if everything turns out to be dream. Are we, indeed, the stuff that dreams are made of, or do we stuff our dreams with what we’d like to be made of? On the other hand, maybe this is all a metaphor about storytelling, and how stories have changed, maybe for the worst, as the mode of telling moved from verbal to paper to screen-based. Maybe, because it’s kind of hard to tell. Which, of course, when you are considering what is “real,” particularly in the non-real mode of storytelling, is the point. I think.

The crown jewel of Datlow’s Subterranean is “Vacancy” by Lucius Shepard. Cliff Coria is a middle-aged, former B-movie actor living a humdrum existence off his residuals and used car salesman income where an afternoon’s meaningless sex is the high point of his week. The title reflects both Cliff’s existential state and a sign displayed at the Celeste Motel, located across the street from his place of employment and which, given the free time he has between selling cars, perks his curiosity. “…something funny may be going on. He might never have noticed anything if he hadn’t become fascinated by the sign in the office window of the Celeste. It’s a No Vacancy sign, but the No is infrequently lit. Foot-high letters written in a cool blue neon script: they glow with a faint aura in the humid Florida dark: VACANCY” (p.53)

There’s a room where people register for the night, but then seem to disappear entirely the next day. Adding to the mystery is that the Asian motel owners are enthusiastic fans of Cliff’s action pictures shot in the Philippines. A typical kind of Twilight Zone scenario, except for the way it plays out is far beyond your typical horror story.

The horror of what happens in the motel room, and particularly of what happens to Cliff, is the horror of chances missed, the inadvertent harm caused to others during the pitiful effort to make it through daily existence without thinking too much about it. Vacancy, in other words, when the “No” prefix of the neon light cannot be controlled, when you finally figure things out, but it’s way too late to do anything about it.

While “Vacancy” gets a bit violently graphic in detail, it’s not gore for the sake of gore. Over at Apex, I’m not too sure if this is the case. Geoffrey Gerard’s ” Cain XP11″:

…Sweet Abigail. I held her liver, uterus, and heart, fingers pushing through the membranes which held each in place. Like reaching into a pumpkin to make a Jack-o-Lantern. Her intestines spilled more vomit and fecal matter over my lap. They were like large worms squirming in my hands before I lay them across the floor.

— p.75

Yuck. Now, while I understand the tradition and purpose of this kind of vivid description, which dates back to Poe, not to mention, for different purposes, Greek heroic fables, generally this sort of thing usually just isn’t my cup of tea. Gerard has an intriguing premise: somehow a group of serial killers has been cloned as part a government experiment of uncertain objectives. The killer clones, which have not matured beyond adolescence, have, however, escaped. The detective who is trailing them has secretly taken along one of the clones, though whether it is to gain insight into the likely actions of the killer clones or to prove that “bad boys” can somehow be made good, is uncertain.

As this only one installment in a continuing series, I can’t tell if it’s worth working your way through the gore to get to some greater significance beyond a prose slasher movie. I suspect that there is, but I’d hate to have to get through it all to find out it isn’t.

Things aren’t quite as gruesome with Cherie Priest’s leadoff story, “Bad Sushi,” a nice riff on “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.” Baku is a Japanese veteran of World War II in the South Pacific. While in a boat evacuating an island from an American invasion, Baku topples into the surf and is grabbed by some kind of tentacle. Fortunately, he has a steel carbon knife to hack away the curling limb of whatever it was. Sixty years later, Baku is a sushi chef, and the whiff he gets of the restaurant’s new fish shipment smells oddly familiar, like something he cut a long time ago. Because of the revulsion he feels for the smell, he won’t eat what he prepares. The new fish brings in a lot of new customers, and the restaurant becomes widely popular. Meanwhile, people are starting to act strange…Even though you know how this goes, there’s a nice twist at the end. And just because you’ve eaten here before doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy another good dinner.

Also working familiar territory is “Pigs and Peaches” by Patrice E. Sarath, a metaphor about AIDS and loss of innocence. Again, you know where this is going, but the post-apocalyptic setting of some sort of communicable Alzheimer’s is nicely staged, and the resolution echoes how a victim is trapped in circumstances others, even loved ones, can’t begin to comprehend.

In “Memories of the Knacker’s Yard,” Ian Creasey ponders whether it might at times be a good idea to willfully forget. The narrator is a detective who in order to discover a murderer travels to Ghost Town to interview the victim in the spirit realm. But to navigate his way in, the detective must remove from his memory his life as a policeman, which if the dearly departed in the seedy end of the afterlife detected would have dire consequences. Putting aside the question that if it were actually possible to interview a murder victim, would anyone risk committing a crime for which they would undoubtedly get caught, this is a nice piece of noir that considers questions of identify, even when we don’t much like who, or where, we are. In the end, it’s better than the alternative.

Speaking of which, a magazine that used to have “alternative” in its title has recently been resurrected with a new moniker. More about that next time…