Short Fiction Review: Tin House

By David Soyka

Copyright © 2008 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

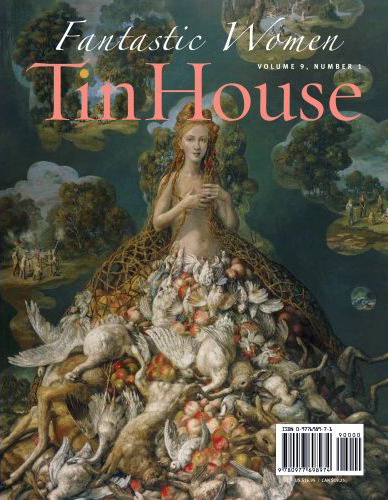

Tin House Issue #33: Fantastic Women

($17.00 postpaid)

The “Fantastic Women” themed issue of Tin House (Volume 9, number 1) was rightly named by Amazon as a “10 Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of 2007.” However, this quarterly being a “literary” magazine, there actually isn’t any science fiction (the one possible exception is Lydia Millet’s wonderful “Thomas Edison and Vasil Golakov,” in which the famed inventor attains metaphysical illumination by continually re-running a film of a circus elephant’s Christ-like electrocution conducted through his technology) and the fantasy owes more to Angela Carter than Tolkien. To underline this genealogy, the one non-fiction essay offered by advisory editor Rick Moody — interesting that a man whose work isn’t typically associated with the fantastic gets to be an editor of female “fantasy” writers — recounts his experience as a student who happened upon a writing workshop taught by Carter. (Anyone who has ever taught writing will appreciate the anecdote here of Carter’s forthright honesty in noting Moody’s copy of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and then her pile of student papers and saying, “I wish I was reading that instead of these.”)

So here we have along with what’s described as “sublimely wicked poetry” by Rae Armantrout, Willa Carrol, Thalia Field, Tedi López Mills, Lucia Perrilo, Paisley Rekdal, Mónica de la Torre, and Anne-E. Woods, along with some of the usual suspects (at least to me) of Millet, Kelly Link, Aimee Bender, Rikki Ducornet, and Shelley Jackson, as well as Hane Avrich, Kate Bernheimer, Judy Budnitz, Sara Shun-lien Bynum, Mary Caponegro, Lucy Corin, Julia Elliot, Samantha Hunt, Miranda July, Stacey Levine. Miranda F. Mellis, Alissa Nutting, Stacey Richter, Julia Slaving and Gina Zuker as exemplars of “Postmodern Women Writers” of “outlandishly inventive fiction.”

Well, that’s as good a description as any, though some of the stories seem outlandish just for the sake of being inventive, rather than for any conventional storytelling purpose. Which, admittedly, may be the point.

For example, in “The Coffee Jockey,” Mellis appears to be commenting on contemporary ennui via a series of disconnected scenarios involving reality shows and the willingness of people to wait in long lines for overpriced caffeinated drinks (though perhaps that is also a type of reality show). Now, there are some good lines here, but I don’t see how they all add up. Consider the opening. “The people were lost. They got lost on their way to the reality show. They got lost and they couldn’t find the reality show. The reality show was lost. By the time they found it, the reality show was over.” Okay, that’s a clever depiction of modern miasma. But, I’m not sure if a series of trenchant observations expressed through declarative sentences necessarily constitutes a narrative. Even while I liked the metaphor that life is like standing in line waiting for a cup of coffee that can’t possibly be worth the time and expense, the set up in describing the woes of the various people in queue just went on too long to hold my interest. Starbucks is currently reorganizing itself to recapture its original entrepreneurial spirit and focus more on what does well — making coffee — and ridding itself of ancillary tangents. I think the same might be true of this story — there’s just too much stuff going on that, while sort of connected, just didn’t make me want to stay in line.

Considerably more inventive is Jackson’s “Word Problem.” The title refers to the school math test, which here is elevated to the metaphysical level of applying a formula to predict someone’s death based on the quality of life experiences. The protagonist, Hen3ry (the mixture of numbers and letters reflecting the title) is literally carrying someone’s death on his shoulders, heading towards some unknown destination (which, after all, is true of all of us). Consider this excerpt as an example of the postmodern (which some might argue is a literary model synonymous with obfuscation):

This might be a good time to pause, future corpses. The Institute men are stuck in the sentence describing them. The sentence says, They are sinking fast. But the sentence itself is standing still. This is the difference between life and death. It is tiny but real.

Love the line about “future corpses,” which, alas, we are all destined to become. And I sort of get the metaphor, you know, if you’re not more engaged than talking about life than living it, then you might as well be dead. But then there’s this whole shtick about plugging this into a mathematical formula, and what this exactly this has to do with Hen3ry and his quest to offload the death he’s carrying, and, well, I just get lost. As with the Mellis story, there are parts of this I really like, I’m just not sure how they all come together to make a story. Then again, I’m thinking of “story” in a conventional sense, and the whole point here is to transcend conventionality.

Along the same lines, there’s no doubt a prospective master thesis in figuring out what Thalia Field is talking about in her 16 page poem, “Parting”:

LOOK

There’s no time to her, she’s not working. Her

difference, that anamorphic smear, doesn’t fool us.

There’s no appreciation of movement against things

themselves moving, so one must, to see movement,

look from the ocean’s angle, offshore against the

backdrop of fences and parking lots where the vanity of

progress can be detected.

Anamorphic is a technique to capture or transfer a widescreen image to 35 mm film; so “anamorphic smear” is an interesting image of someone moving faster than her background, which could mean intellectually and not physically. Or maybe not. Exactly how this doesn’t fool anyone or connects with the backdrop of a “vanity of progress” — maybe a parking lot full of Mercedes and BMWs — I don’t know, but keep a concordance handy if you try to figure this out.

Fortunately, not everything here is nearly as abstruse, though certainly straightforward narrative is far and few between. “Beast,” by Samantha Hunt, in which a couple quite literally discover their true animal natures, is almost conventional in comparison to Jackson. Similarly, Zucker’s “A Hard Worker” depicts a girl trapped in prostitution; though the prostitution is somewhat fanciful, the moral points to the more gritty reality. In keeping with the theme of exploitation and retribution, as you might expect in “feminist fiction,” there are animated dolls (Richter’s “The Doll Awakens”), middle class housewife torpor (“Abroad” by Budnitz and Ducornet’s “The Dickmare”) fairy tale retellings ( “Whitework” by Bernheimer and “The Young Wife’s Tale” by Bynum, which could be cross categorized with the previous housewife torpor) and weird coming of age tales (Elliot’s “The Wilds”).

One of my personal favorites is Lucy Corin’s “Mice.” The narrator is an unusually big and hairy guy, mired in middle-class existence with a dog and a young child and a wife who doesn’t desire him. The main thing she wants him to do is get rid of the mice in the house. But, this is a big hairy guy who’d prefer not to hurt a mouse, which leads to some profound changes from which to ponder the exigencies of humdrum existence.

Another is Kelly Link’s “Light.” Like the Jackson and Mellis tales, this one also has a lot of wild weird tangents, but, in this case, at least for me, knit into a more readily intelligible structure. Lindsay is a young professional on the bar circuit looking for love. Lindsay’s job is a little unusual though; she works for a company that warehouses “sleepers,” people found comatose that nobody knows what to do with. Her job is to manage the paperwork and make sure the security guards stay awake (even in fantasies, you can’t avoid the mundane). And, then, there are these “pocket universes,” alternate themed realities owned by the Chinese government that you can visit. However, much as happens to Corin’s protagonist, maybe sometimes you can escape from your life for awhile, but you never can really hide, no matter how hard you try otherwise…

This is truly a fantastic issue, both in terms of subject matter and reader experience. Even though one or two stories might extend beyond your grasp, don’t let it escape you.

One thought on “Short Fiction Review: Tin House”