A Storm of Another Kind: Mother of Storms by John Barnes

|

|

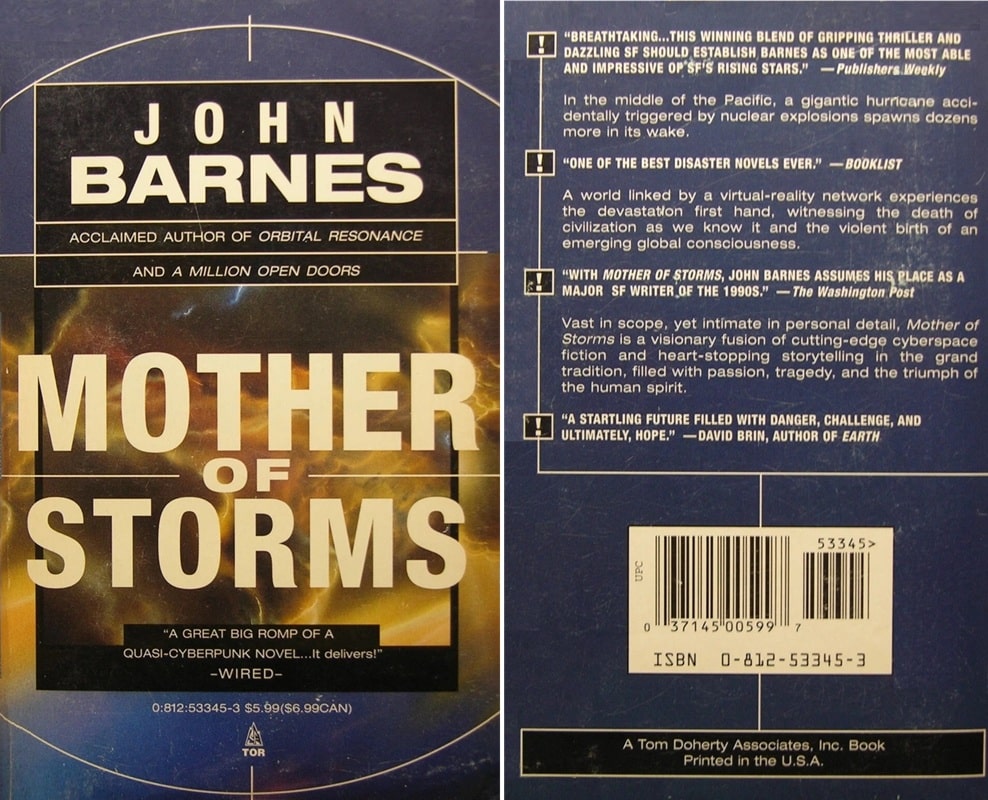

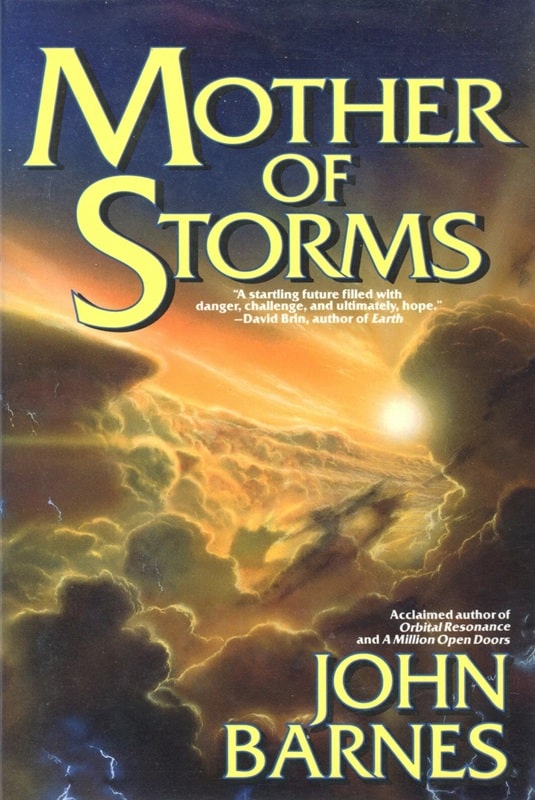

Mother of Storms (Tor Books, July 1994). Cover by Bob Eggleton

One of science fiction’s subgenres is that novel that emulates the style of bestsellers — bestsellers as they were before the fantastic genres became a big part of the cultural mainstream. Michael Crichton, for one, specialized in this type of writing, from The Andromeda Strain to Jurassic Park; but other writers take it up from time to time: Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle in Lucifer’s Hammer, David Brin in Earth, and much more recently Andy Weir in The Martian and Harry Turtledove in Supervolcano.

Some markers are common in this sort of book: reduced use of expository passages, a more demotic prose style, a near future setting that’s easy to imagine, multiple viewpoints and a large cast of characters — and despite this, a much reduced presence of characters who have a detached, scientific view of the world. John Barnes’s Mother of Storms is a classic example of that kind of science fiction.

That’s not at all to say that it lacks substance. In fact, I think it’s fair to say that Mother of Storms shows that neither this form, nor this style, prevents a book from being admirably solid science fiction.

The book’s title reflects its primary science-fictional premise: The release of massive amounts of methane, trapped in clathrates underneath the ocean, into Earth’s atmosphere triggers a vast increase in greenhouse gas effects, followed by hurricanes on a scale exceeding the worst storms in history. Barnes gives his readers a scientific explanation, only a few times longer than that sentence; he goes on to vivid scenes of the massive destruction that follows, including the extermination of entire island nations from the Caribbean to the Pacific; but above all, he shows the social transformation that that destruction creates, which is a storm of another kind.

But this isn’t a Wellsian science fiction story with only one fantastic premise. Barnes also envisions major developments in information technology, which might be regarded as another kind of storm. Some of this is the kind of thing we’re already beginning to see; for example, we learn early on about a young woman who doesn’t like going out into the desert with her boyfriend, because they end up outside the reach of wireless networks, and when she looks at the plants she doesn’t see texts telling her what they are and how to appreciate their environmental significance, a bit of social satire premised on virtual and augmented reality.

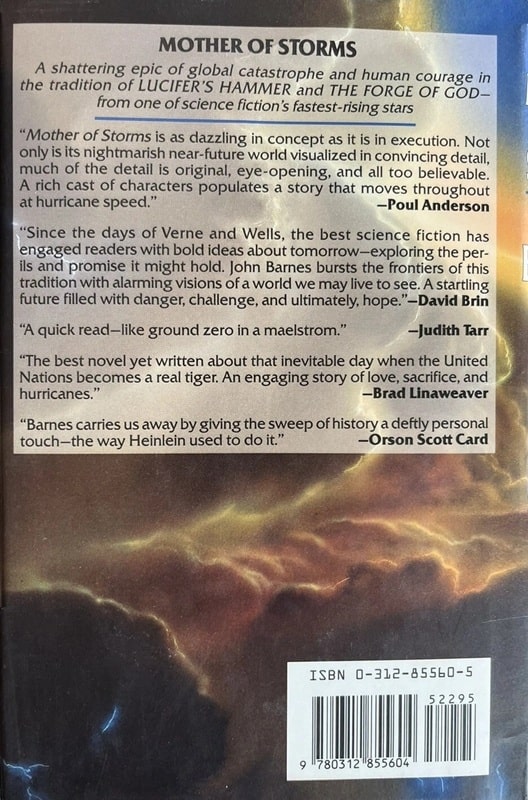

Mother of Storms (Tor, May 1995). Cover by Bob Eggleton

Some is just a few years ahead, as when characters travel around in self-driving cars that let them lie down and nap for a few hundred miles. And some of it may be further than that, such as the complete solution of the problem of transferring data between human brains and electronic circuits.

Three of the main subplots grow out of this last. One is the utilization of these data transfers for pornography — and, grimly, for sadistic pornography in the exact sense, pornography that eroticizes torture and murder, recorded from the brains of both the murderer and the victim. Another is a world wide media complex based on recording from the brains of trained experiencers, who investigate crimes and disasters, but also provide an outlet for their audiences’ fantasies.

Last, and most significant for the outcome of the plot, is the discovery that programs for optimizing other programs can cross the interface the other way and start optimizing human brains — as a result of which two recurring characters undergo a kind of apotheosis. Ingeniously, Barnes manages to connect all of these with each other.

How far in the future is this novel? It was written in 1994. The Kirkus review says that it’s set in 2028. That was comfortably in the future back then. But at the same time, it was close enough not to require assimilating an entirely different fictional world; indeed, it had baby boomers still around, and younger characters referring disparagingly to “boomtalk.” And now it’s not far at all: 2028 is the year of the next presidential election!

It’s not really the job of science fiction writers to be prophets; no one’s science fiction is set in the real future. But at the same time, it’s an entertaining game to score a writer’s hits and misses. One of its big background events may be either a miss or too early: Europe’s expulsion of the “Afropeans,” people with African parentage born in Europe, who become refugees in the United States — along with Berlina Jameson, daughter of a black American soldier and a German prostitute, caught up in the diaspora, whose effort to revive old-style journalism becomes a continuing thread and a kind of Greek chorus.

|

|

Mother of Storms (Tor Books, June 5, 2012). Cover uncredited

The whole idea that journalism has been dying out in favor of scripted experiences shared by millions of people seems all too close for comfort! It also leads to another continuing thread, in which Synthi Venture (a telling name!) becomes a kind of influencer through her experience of the global storm. The passages about the “Deeper” movement, young people who seek consensus in everything, consider any personal enjoyment mildly shameful, and say things like “We’re gentle in our anger” might suggest that Barnes had mentally locked in on today’s controversial images of being woke, thirty years ago.

But this story also shows one of the other faces of science fiction: The portrayal of events on a cosmic scale too big for human beings and even human civilizations to cope with (as in H.G. Wells’s early “The Star,” which shows Earth narrowly escaping a cosmic cataclysm). The great storms of Barnes’s future may have been triggered by military weapons, but they can’t be put back the same way! Entire societies are destroyed in a few pages, from Bangladesh to the Hawaiian islands.

Barnes does suggest that a solution is possible — but one that rests on the old Technocratic idea of unleashing the engineers from economic and bureaucratic control, now in a transhumanist version that changes the engineers themselves. In a way, both Berlina and Synthi emerges as oracles of these new godlike beings. The cross talk between brains and computers that permeates Mother of Storms seems a lot more topical now than it did even five years ago.

I have to admit that I decided to reread Mother of Storms with some ambivalence. I remembered its story of brutal rape/murder, presented in the kind of graphic detail that made de Sade a literary archetype, which is ghastly to reread, even forewarned.

And this time it struck me that there’s more to it than that. On one hand, while Kimbie Dee Householder’s violation leads to private vengeance, it never leads to public judgment. And on the other, it’s not as isolated as it seemed in retrospect: I could see that the (more or less) consensual sexual acts in the novel had similarly ugly implications, from the honeymooning couple whose digitally recorded Hawaiian trip combines harsh social satire with lethal weather (both apparently found erotically charged by their producer) to the engineering student who discovers Synthi’s darker side. Barnes seems to want to show human sexuality itself as a destructive force capable of ruining human lives; even at its best it’s often a bit creepy.

This darkness of vision is common in his fiction, from novels that I enjoy a lot to others I couldn’t finish. Mother of Storms is right on the margin for me: I did want to reread it, and I might do so again someday, but I’m glad to have gotten through it again. But getting through it calls for a certain blunting of the sensibilities. And that may be one of its most bestseller-like aspects: Its reliance on a kind of sensationalism for which that blunting is an appropriate, or at least perhaps necessary response.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last article for us was a review of Torchship by Karl K. Gallagher. See all of his recent reviews here.