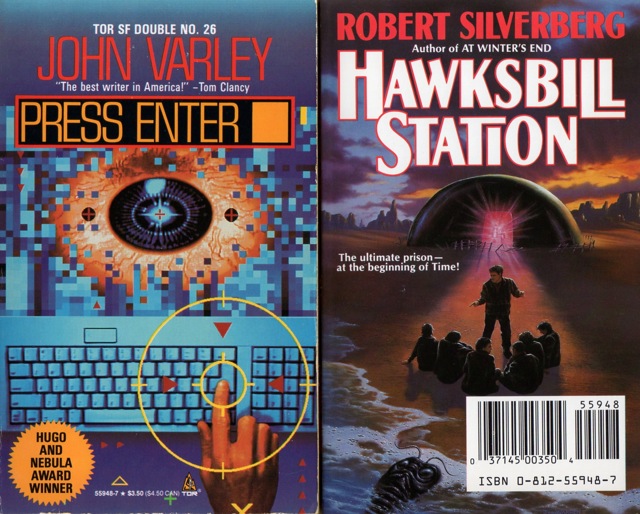

Tor Doubles #26: John Varley’s Press Enter and Robert Silverberg’s Hawksbill Station

Cover for The Death of Doctor Island by Ron Walotsky

Tor Double #26, originally published in October 1990, contains the fifth and final story by Robert Silverberg. It also contains the second of three stories by John Varley.

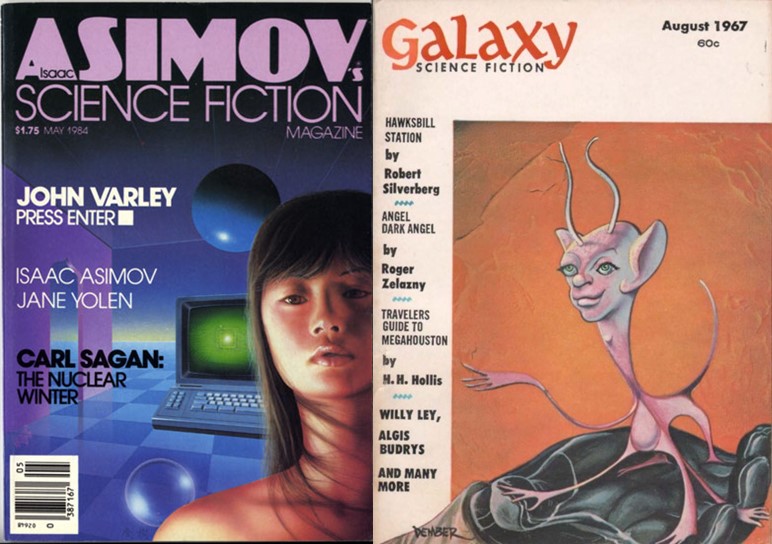

Hawksbill Station was originally published in Galaxy in August, 1967. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award. Set in the Cambrian period, before land animals or plants have evolved, it focuses on the titular prison, sent back in time from the twenty-first century to house political dissidents.

With twenty years of imprisonment under his belt, Jim Barrett is the leader of Hawksbill Station, where he, like everyone else is serving a life sentence, since the machinery that delivers supplies and other inmates can only send from the twenty-first century, referred to as “Up Front.” There is no escaping their sentence or parole. Part of Barrett’s self-appointed job is to monitor the well-being of the others who have been sent to Hawksbill Station and determine who has lost their sanity by the conditions in which they live.

The prisoners have created a peaceful society, with little conflict between them and each looking out for each other’s well-being and to make sure nobody endangers their colony. The society they’ve created may be a little to Utopian, although Silverberg hints that it took a while to get this way. All of the people who were sent to Hawksbill Station prior to Barrett’s arrival have died and one of the inmates, Ned Altman, prior to his current attempts to create a living woman out of mud, may have attempted to rape the other men, although they seem to have moved past that episode.

While Barrett has the respect of the men in the camp, he is also dealing with his own issues. Each year, he led an expedition around the Inland Sea to check out the unchanging landscape, but also to see if they could find anything sent from Up Front that had gone astray. In the previous year’s trip, his foot was crushed, leaving him reliant on a crutch to walk and making him feel his own aging and mortality, although he seemingly never considers that it would leave him ripe for a takeover attempt.

Silverberg spends a good amount of time describing his setting before focusing on the serpent in his Eden, in the form of Lew Hahn. Hahn is introduced early in the novella as a new arrival at Hawksbill Station, but his reaction upon arriving isn’t entirely typical of the other inmates and he is more reticent about his background than most. Barrett assigns him a bunk with another inmate and various characters attempt to learn things about Hahn, but it is clear that he doesn’t want to talk about the crimes that caused him to be sent back. More concerning to Barrett is that he doesn’t seem at all versed in the sort of thought crimes that caused all the others to be sentenced to Hawksbill Station.

In this sort of environment anything out of the ordinary is going to lead to suspicion and paranoia. Silverberg has already indicated that many of the inmates suffer from forms of mental stress, from Altman’s attempts to make a woman to Don Latimer, Hahn’s roommate, who is trying to use mysticism to return to the Up Front. The discovery that Hahn was, in fact making notes about the inmates further heightened the sense of paranoia in the community and Barrett took his role seriously of maintaining the calm of the prison.

As the creator of the rules of time travel in the world of Hawksbill Station, Silverberg is able to tweak the rules to serve his needs, which he does, but in a sensible manner to advance the story and tension of the novella. While the ultimate confrontation between Barrett and Hahn that leads to the explanation of what is happening may be a little too easy, it leads to a decision which makes complete sense, but isn’t telegraphed by the story.

This is an interesting time to be reading Hawksbill Station. Although set a billion years in the past, the inmate of the prison are all from a period ranging from about 2010 through 2030, meaning we’re currently living in Up Front, when a conservative government uses Hawksbill Station to permanently get rid of liberal trouble makers.

Universe 3 cover by Bob Silverman

Press Enter [] was originally published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in May, 1984. It won the Hugo Award, the Nebula award, the Seiun Award, the Locus poll, and the SF Chronicle poll.

Victor Apfel was minding his own business, a preoccupation he had spent a lifetime honing, when his phone began to ring. Every ten minutes a recorded announcement would interrupt him, The recording urgently invited him to visit his next door neighbor, Charles Kluge. Apfel eventually gave in to the constant commands to discover that his neighbor, who he hardly knew, had apparently committed suicide.

Apfel responded properly, contacting the police to investigate the death, but that’s one of the last things to go as it should in the story. When the police, led by Osborne, arrive, they question Apfel, but quickly decide he isn’t a suspect. However, they also allow him to remain on the scene of the crime, ignoring that he could be a witness. They also hired Lisa Foo to go through the computers which littered Kluge’s home, but failed to provide any real supervision for her investigation.

Surprisingly to Apfel, because he barely knew Kluge, Kluge not only called on him to find his body, but also arranged a massive inheritance go to Apfel. Kluge’s death also released information that he didn’t trust any of his neighbors and released their secrets: affairs, crimes, and other unsavory actions. Kulge felt that Apfel, alone, lived a spotless life, although Apfel would disagree.

Although Kluge’s death is written off a as a suicide, Apfel, Foo, and Osborne are all convinced it was a murder, but Osborne must go along with the official findings. Foo’s investigations, however, show that Kluge had used computers to create an alternative world to live in. As far as the official world was concerned, nothing about him existed. There was no record of his house, he manipulated wealth so that it was wherever he needed it, he had designed enough computer systems with backdoors that he could get in wherever he wanted.

Although Varley’s main focus is on Apfel and Foo, neither are particularly sympathetic and Foo, especially, comes across as being amoral, while Apfel, at least, feels pangs of conscious about what she is doing and what he knows. Their burgeoning May-December relationship drives much of the story and the two reveal their secrets to each other, Apfel having suffered as a prisoner of war and Foo suffering as a refugee in war-torn southeast Asia. Not only do their share their backgrounds, which make them distrustful of the war around them, but Foo shares information about Kluge’s computers with Apfel that she doesn’t share with the police, partly because she uncovers things she doesn’t trust to the authorities, but also because she wants to hold onto the secrets in case she ever needs them. At the same time as they grow closer together, there is never a sense that they have a relationship that will last. Apfel is well aware that it is probably fleeting, but despite his generally hermit-like habit, he’s happy to enjoy their life together while it lasts.

Although originally published in 1984, Varley does an excellent job of describing twenty-first century hacking and computer crime, including elements of artificial intelligence, clearly extrapolating from the nascent personal computers of the time to their eventual capabilities. At the same time, he presents a world of hackers who have their own sense of morality which often can be used as a cover for doing whatever they want to do. He also introduces the idea that no matter how accomplished a hacker Kluge or Foo are, there is always something bigger and better than they are, whether it is an individual hacker or an organization which is more aware of their activities than they understand.

Many other stories which focus on hacking posit the idea of a white hat hacker who does what they do for good reasons and use hacking to improve society. Varley’s hackers don’t buy into that concept, neither are they villains who use hacking to commit crimes, at least not crimes that have victims. Instead they appear to be people who understand the power of computer technology and are trying to push the boundaries to figure out what they can do, whether it is on their own, as Apfel did, or building on the shoulders of those who came before, like Foo. Morality barely comes into the picture. It is simply a matter of doing what they can.

The cover for Hawksbill Station was painted by Jim Warren. The cover for Press Enter [] was painted by Peter Gudynas. This was the last volume published in the tête-bêche format. All subsequent titles were published in a more traditional anthology format.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

So this is the original Galaxy version of Hawksbill Station? I thought that the first, shorter version was better than the novel, which felt more than a little diluted.