Third Time’s the Charm: Avram Davidson’s The Enemy of My Enemy

We all have our favorite obscure or neglected authors, writers we get touchy about and on whose behalf we’re instantly ready to jump on top of a table, ball up our fists and yell at the top of our voices, “HEY!! Don’t forget THIS GUY!!!”

For me, Avram Davidson is at the top of that list. I’ll knock over the Parcheesi board for him any day of the week.

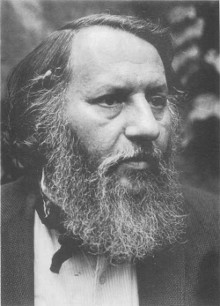

As is often the case with such semi-forgotten writers, he wasn’t always obscure or neglected; though never a behemoth like Heinlein, Clarke, or Bradbury, during the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s Davidson was quite well-known. He had three World Fantasy Awards to his credit, won a 1958 Hugo Award for his delightfully paranoid short story “Or All the Seas with Oysters” (read it and you’ll never turn your back on a closet full of coat hangers again) and was briefly the editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Few people in the genre were more well-respected or personally beloved.

As is the way of things, however, as younger authors step forward, older ones fall back, especially when they’re no longer producing new work, and as time passes more and more of their output falls out of print and they fade from whatever share of the reading public’s consciousness they once commanded. It’s not a conspiracy — it’s just that there’s only so much room on the bookstore shelves and youth, as they say, must be served.

The books these older authors wrote are still around, though, ready to be found on eBay or in used bookstores or in any of the other usual places, and often at bargain prices, too. All of these options make it a great time for… ahem… mature readers who want to renew an acquaintance with an old favorite or for adventuresome younger readers who want become familiar with someone who was only a name to them before.

I’m one of those mature readers, and on my summer vacation from my teaching job, I hit the “old friends” paperback pile pretty hard; in fact, I have a couple of bookcases filled with nothing but such summer reading — science fiction, fantasies, mysteries by Tanith Lee, Doc Smith, Fred Pohl, Cornell Woolrich, Ron Goulart, Donald Hamilton, C.J. Cherryh, Poul Anderson, Otis Adelbert Kline… you get the idea.

Oh, and Avram Davidson.

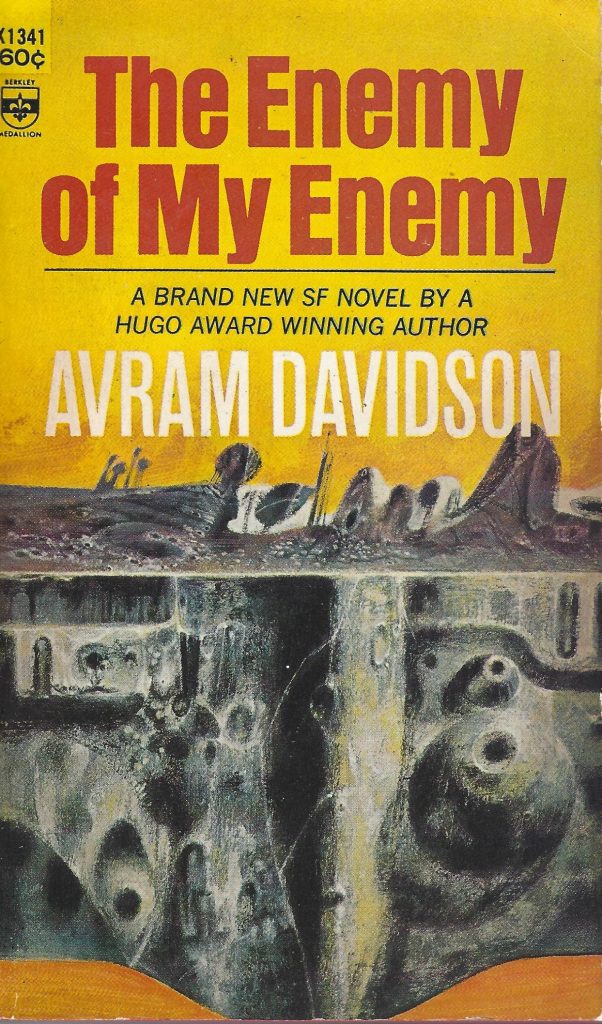

A couple of weeks ago, I pulled a Davidson book off a summer shelf, and not for the first time, either. His 1966 science fiction novel The Enemy of My Enemy is a book that I had tried to read twice before, and I never got more than two or three chapters in.

This time, I was determined to make a go of it, and after almost giving up again (this time after four chapters) I saw the book through to the end. I felt I owed it to myself and to Davidson too, especially considering that my problems getting into the novel were my fault, not the author’s.

You see, Avram Davidson probably shouldn’t be on my summer shelf at all, because so many of his books contradict the idea that a 160-page paperback original will be a fast, fun, undemanding read. Fast? Davidson’s prose is usually too quirky, too knotty, too dense to just zip through — or for me to just zip through, anyway. I’ve found that an Avram Davidson novel requires an unusual degree of concentration, and I always have to slow down and take my time with even his shorter books. That was certainly the case with this one.

Undemanding? Everything Davidson wrote was ambitious in its way, and you can always feel him working to extend himself — and therefore extend his readers, too. He was never just punching the clock to get a paycheck (not that Berkley gave him much money for something they would sell as a sixty-cent paperback); even in his lightest works, he always had something serious to say.

Fun? His books are often very entertaining, but they’re never mere formula fun; when you pick up something by Avram Davidson, even a paperback space opera, you had better be ready to hold up your end.

I knew all that going in, so I should have been ready. Well, third time’s the charm.

The Enemy of My Enemy is set on Orinel, an earth-like planet of moderately advanced technology and many nations. (It is hinted that long ago, Orinel may have been an earth colony.) The story begins in Pemath, a rough-and-rowdy commercial nation where criminal Jerrod Northi (he makes his living in bursting-with-corruption Pemath Old Port as a sort of pirate/hijacker) is running for his life; someone keeps trying to kill him, and they’re getting too close for comfort.

Since Northi has no idea who has it in for him, he can’t take that party out first. The only course open to him is to get out of town — way out of town.

Fortunately for Northi, he’s in a science fiction novel, so he goes to one of his underworld contacts, who arranges for him to visit a mysterious group called the Craftsmen, who (for a price) physically alter Jerrod so that he can pass for an inhabitant of an island nation called Tarnis. The Tarnisi, while human, are visibly different from other Orinel natives. True Tarnisi have the “seven signs” — green eyes, long fingers, smooth and hairless bodies, full mouths, slender feet, melodious voices, and long, tipped ears.

Northi chooses Tarnis for his relocation because he’s always wanted to go there, beginning in his hardscrabble days as a street orphan. He (and most everyone else, too) thinks of Tarnis as a kind of Eden, where it’s always summer and the living is easy.

One in Tarnis and passing as a Tarnisi, Northi (now going by the name Tonorosant) at first slips smoothly into his new environment, a task made easier by posing as a “returning exile”, a Tarnisi who has spent many years living abroad and who is now returning to a home where no one really know him.

Northi’s adjustment doesn’t stay smooth for very long, however, as he quickly finds that Tarnis, instead of being the ideal island that the rest of Orinel thinks it is, is instead a faction-riven, strife-shaken mess, a nation roiled by constant class, racial, and political conflicts.

You almost literally can’t tell the players without a scorecard. Among the Tarnisi, you have the landed aristocracy, indolent, complacent, pleasure-seeking and aesthetically-inclined (a favorite pastime is painting subtly-nuanced pictures of leaves). This group is countered by resentful Lacklands who — you guessed it — don’t have any land. Two more native groups are the Volanth, the aboriginal inhabitants of Tarnis, nasty, brutish and short-tempered, and kept in perpetual poverty and ignorance. The Volanth are the one group that everyone can look down on, even the Quasi, people of mixed blood — Tarnisi and Pemathi (there are a lot of Pemathi who work as servants to the aristocracy or doing other things considered beneath a Tarnisi), Tarnisi and some other Orinel native, or even… shudder… Tarnisi and Volanth.

Stir in the two main Tarnisi political factions, the Lords and the Guardians, always at odds and struggling for mastery, add the meddling of other nations like Bahon and Lermencas, both seeking a foothold in Tarnisi in order to exploit the country’s resources for their own ends (there turn out to be many Tarnisi who are actually shape-changed foreigners like Northi, and who are agents of some faction or foreign government, or even of the Craftsmen themselves, who are stirring things up in order to forward their own hidden agenda) and you have quite a rich mixture.

Northi soon finds himself being pulled in all directions. The various factions try to recruit him to their causes while he struggles with his feelings of disgust for the shallow aristocracy and sympathy for the Quasi and the oppressed Volanth, feelings that are complicated when he finds out that he’s a Quasi himself; it was easy for the Craftsmen to change him because being part Tarnisi to begin with, he already had some of the seven signs.

After a lot of wrangling and secret meeting and hushed conversing and startled discovering, the story ends with an uprising that unmasks and expels the foreigners and leaves the inhabitants of Tarnis, in all their different varieties, to hammer out an equitable way to live, by themselves, for themselves, and among themselves. It’s a job that’s only beginning in the last paragraph of the book, and Davidson isn’t silly enough to suggest that it’s going to be easy or even ultimately successful.

I’m glad that I finally read The Enemy of My Enemy. Every bit of the novel is sharply conceived and every sentence is alive and lively; there’s nothing slack or lazy in the book. Very much like Jack Vance, Davidson creates fabulous worlds in almost encyclopedic detail, and also like Vance, he often presents those worlds in a baroque prose style that requires more than the usual amount of focus and patience from a reader. When it works, you can feel lifted out of the everyday and immersed in a delightfully sensuous new environment, but you can also feel frustrated because the immense amount of information and the mannered way of delivering it overwhelm you and keep you from fully knowing just what the hell is going on. That was sometimes the case with The Enemy of My Enemy, which alternately delighted and frustrated me.

The problem is that there’s almost too much in the story to be properly dealt with at such a short length (156 pages in my 1966 paperback edition). There are so many characters, so many factions, so much history and background and culture and politics and intrigue and above and below the surface action that the story doesn’t get a chance to properly cohere; it’s a recipe that needs a bigger pot, especially considering the complex issues of class and racial prejudice that Davidson is wrestling with.

But if the book’s flaws keep it from being a complete success, they’re the kind of imperfections that you only get from an intelligent, highly ambitious writer. About half way through the book, Davidson proves his quality with a chapter in which Northi is drafted to go on a punitive expedition against the Volanth, who have committed some crime against the local Tarnisi.

In that chapter, big-city tough guy Jerrod Northi is shocked speechless by the brutal viciousness and the horrifying irrationality of war, and you feel as if Avram Davidson isn’t making up a single thing — you feel as if he’s an eyewitness reporter. It may well have been so; he served as a Marine Corps medical corpsman in World War Two and then fought in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Terror, despair, sadism, rape, madness — nothing is held back, and for ten pages the Machiavellian politics and rococo prose drop away, and it’s as if Avram Davidson is holding this awful thing called war right in front of our eyes, and saying “Look at it. Don’t turn away; just look.” For that brief space, The Enemy of My Enemy is jolted into a ruthless clarity, and it becomes a stunning book, a brilliant book.

When I finished that harrowing chapter, I just sat there shaking my head, thinking how glad I am that I can go from the new to the old and back again as often as I want, because back there is a place where I can find a writer like Avram Davidson, a writer who’s worth reading even when things don’t quite work, a writer whose lesser books still give you valuable glimpses of how wonderful his best work is.

If you know Davidson, you know what I mean. If you don’t know him, why not give him a try? He wrote so many brilliant books — wide-screen science fiction novels like Masters of the Maze and Clash of Star Kings, learned, literary fantasies like The Island Under the Earth and The Phoenix and the Mirror, and delightful short story collections (he was at his most humorous and inventive in his short stories) like What Strange Stars and Skies and Or All the Seas with Oysters. In a category by themselves are the Dr. Eszterhazy stories, set in an alternate-history nineteenth century that never was, but should have been. If you can lay your hands on the 1990 Owlswick edition of The Adventures of Dr. Eszterhazy, don’t ever let it out of your sight; you have a treasure beyond price.

Heck, you could even start with The Enemy of My Enemy; it may well be that I had trouble getting into it because I’m just not as smart as I think I am. In the wild world of Avram Davidson, anything is possible…

Hey!! Don’t forget This Guy!!!

Hey!! Don’t forget This Guy!!!

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Shouldn’t the Missing Be Missed?

I love the standard of knocking over the Parcheesi board as a measure of an author’s worth. That’s a truly righteous image. Evocative. Thank you for sharing it.

…Trying to think of any authors I’d do that for, now, but am only coming up with individual works. That you’ve got a whole author you would do that for must mean Avram Davidson is really something. So, one question before I seek him out on your say-so: did he write anything that was particularly light-universe/optimistic in character?

That’s an interesting question; I would say that Davidson’s ironic temperament kept his work from being all that “light”, at least his novels. He was probably his lightest in his short stories, and I agree with Matthew that overall they are his best work. The Dr. Eszterhazy stories truly are miraculous, and a good novel to try is one I didn’t even mention (and it’s probably his most well-known one) – Rogue Dragon.

Entirely fair evaluation. Thank you for answering my question. “What Strange Stars and Skies,” “Rogue Dragon,” and the Dr. Eszterhazies will go into my TBR list in that order.

I tend to prefer Davidson’s short stories to his novels. I actually consider him one of the best short story writers ever. Him and R. A. Lafferty deserve a lot more attention.

In a just world, those two would be widely in print. https://www.arriveateasterwine.com/resources

By the way, you can tell how gung-ho Berkley was about this novel by looking at the godawful cover, which not only has no relation to Davidson’s story, but has no relation to anyone else’s story either.

Great blog! Thanks for sharing. Love having Davidson fans on the Avram Davidson Universe Podcast. Let me know if you are ever interested.

Foolishly, I have allowed The Adventures of Doctor Eszterhazy to remain away from my bookshelves. I can take comfort in my copy of The Avram Davidson Treasury, which does contain an amazing number of tribute essays to AD. I think of all his works, I am most fond of his late-life articles in Asimov’s, published under the rubric “Adventures in Unhistory”. Now, there is a collection that needs to be collected!

And the Avram Davidson Society still celebrates his life and work (like his centenary birthday in 2023). My friend Henry Wessells, book collector, publisher, and author, is keeping its website alive (avramdavidson.org) and issuing copies of The Nutmeg Point District Mail electronic newsletter of all things AD.

The Treasury is indeed a dynamite anthology, and I can recommend another great posthumous collection, The Other Nineteenth Century, published by TOR in 2001.

I was quite fond of The Phoenix and the Mirror, an Ace paperback with a cover by the Dillons that I acquired in 1970 (which I sadly don’t remember too much about now). But I never tracked down Davidson’s other novels about Vergil. Has anyone else here read them?

I’ve read The Phoenix and the Mirror, but not Vergil in Averno. Davidson supposedly planned a nine novel Vergil sequence, but only finished the first two and a draft of a third. I don’t know if the draft has ever seen the light of day.

ISFDB lists the 3rd Vergil book, The Scarlet Fig (or, Slowly Through a Land of Stone) as published by Rose Press in 2005, then re-issued as an e-book by Prologue Books in 2012.

Thanks! I wonder if it was published “as is” or if anyone had to polish it/complete it or otherwise put it in shape.

As with other late works (Marco Polo and the Sleeping Beauty, 1998), it is a collaboration with his wife Grania Davis (listed as an editor) and also edited by my friend Henry Wessells.

I read all three Vergil Magus books this year. Vergil in Averno is a prequel that sends Vergil to a ‘heavy industry’ town to do some magical detective work amongst a conspiracy. It’s a darker, more convoluted, more anxious work than its predecessor. The Scarlet Fig is lighter, more of a return to form (and it’s also a prequel, set in between ViA and TP&tM). The plot starts off with Vergil having to leave Rome because he accidentally touched a Vestal Virgin, but then that basically just turns into a travelogue as Vergil sails around the Mediterranean. Davidson seemed to be trying to cram in every scrap of historical or mythological info he could find after years of research on the early medieval Mediterranean. Unfortunately, he did leave it unfinished, but Grania Davis and Henry Wessells did a great job putting it into shape as well as possible, and it’s actually a much easier read than ViA. Both are worth tracking down.

I’ll agree that Davidson isn’t an “easy” read, but his work is worth it. As an example, I first read “The Phoenix and the Mirror” when I was about 16, and approached it as a quick Fantasy read. I got through it, but it wasn’t quick, and I didn’t particularly enjoy it. A few years back, now in my late 50s, I began reading-reading a lot of SF/F classics , and in the case of “Phoenix”, I enjoyed and appreciated the novel much, much more than I had first time around.

I still haven’t read Davidson’s other Vergil novels, but hope not to take decades to get to them!

Thanks for the article, Thomas. I don’t have a summer reading pile, just several bookshelves of books to be read. They are mostly populated with with the shorter sci fi works of the 50s, 60s, and 70s and I find it easier to pick up a 160 page book than something (much) longer. Funny how you mentioned tackling Davidson after two previous attempts, I did something similar this week with “Revelation Space” but the third time wasn’t a charm. It went to my donate pile. As for underappreciated authors, I don’t know if Clifford Simak is one but he is one of my favorites and “City” is my favorite book of short stories. (I have “Strange Seas and Shores” and will have to read that soon). Thanks again

Jim, I think Simak had a higher visibility in his day than Davidson did, but I would place him in the same category now – a writer no longer read as much as he deserves to be, but extravagantly loved by those who do remember him.

Someone on the Bookbub and Amazon teams might agree with you on Simak, Jim. I see his books come through as “deal” books every three weeks or so. It’s conspiring to get his work out to a wider audience, again.

Mostly have enjoyed Simak’s work. He has whip-crack turns of illustrative phrase.

City has my favorite first line of any book: “These are the stories that the Dogs tell when the fires burn low and the wind is from the north.”