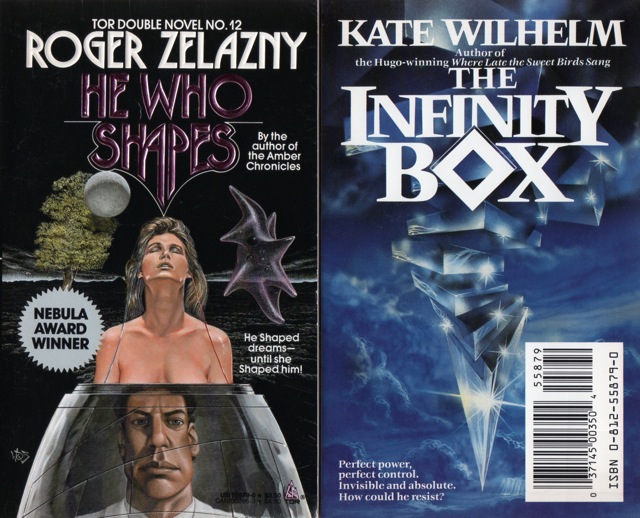

Tor Doubles #12: Roger Zelazny’s He Who Shapes and Kate Wilhelm’s The Infinity Box

Cover for The Infinity Box by Royo

He Who Shapes was originally serialized in Amazing Stories between January and February, 1965. It won the Nebula Award, tying with Brian W. Aldiss’s The Saliva Tree, which appeared as half of Tor Double #3. He Who Shapes is the first of three Zelazny stories to be published in the Tor Doubles series. Zelazny’s original title for the story was The Ides of Octember, which was changed before its initial publication. He eventually expanded the novella to the novel length The Dream Master and the original title was used on the story when it was reprinted in 2018 in the collection The Magic.

The story focuses on Charles Render, a neuroparticipant therapist, and drops the reader into a session, in which Render is creating a reality for his patient, in which the patient is Julius Caesar in a world in which the assassins kill Marcus Antonius while Caesar/the patient longs for martyrdom. Following the session, Zelazny introduces Render and his techniques to the reader in a manner which leaves no room to doubt that Render may be adept and the technical part of what he does. But his bedside manner leaves much to be desired.

His standoffishness extends to other areas of his life as well, as shown by his treatment of his secretary and his girlfriend, Jill DeVille, whom he issues ultimatums to and can’t put before his own wants. Their entire relationship seems to be a power struggle in which Render must come out on top and it isn’t clear why she puts up with him,

The only person in the novella who seems to be able to earn Render’s respect and get the better of him is Eileen Shallott, a blind woman who accosts him at his club one evening. Shallot is interested in becoming a neuroparticipant therapist and wants Render to help her despite the fact that she can’t see. Despite warning Shallott of the dangers and difficulties of training her, Render eventually decides to take her on, partly against his better judgment, but also because of his lust for her, despite his relationship with DeVille.

In addition to Render’s treatment of DeVille, his antagonism toward Shallott’s enhanced seeing eye dog, Sigmund, and his overprotectiveness of his son, Peter, who has a minor accident at his boarding school leading to Render’s threatening the school for their negligence, despite the fact that Render himself treats Peter more as an obligation than a person, makes him a protagonist who is unadmirable. In his dealings with Shallott he rejects not only his own advice, but also the advice of a respected colleague.

One of the things that draws Render to Shallott is how strong-willed she is. She managed to make it through medical school despite her inability to see. It is this very attribute that makes Render willing to take her on as a student. It also means that once she begins to understand what it means to shape the neuropsychological landscape, she is able to usurp his control over what happens in the dream world. Render suddenly is less the Shaper and instead survives in the worlds at Shallott’s whim, a situation which he dislikes and is unable to control.

The story descends into a nightmare situation for Render, but it also feels incomplete. Zelazny indicates, through Sigmund’s concern for Shallott, that the therapeutic experience and training is taking a psychological toll on Shallott, which Render dismisses, but something is causing her to create the world Render finds himself in. It almost feels as if he has done something to make himself her target, although that isn’t explored.

Unfortunately, Zelazny’s decision to focus on Render is to the detriment of the story. His personality is not one to render the reader sympathetic to the character, even if he doesn’t deserve the fate that comes for him. DeVille and most of the other supporting characters are little more than caricatures, with Shallott and Sigmund perhaps the most fleshed out aside from Render.

When I reviewed James Tiptree, Jr.’s The Girl Who Plugged In, I wrote it “offers a very different experience from reading it when it was initially published in 1973 or reprinted as part of the Tor Double series in 1989.” The same is true for He Who Shapes. Modern readers will clearly recognize the technology Render is using as a form of virtual reality that allows him to share a world he builds with his patients.

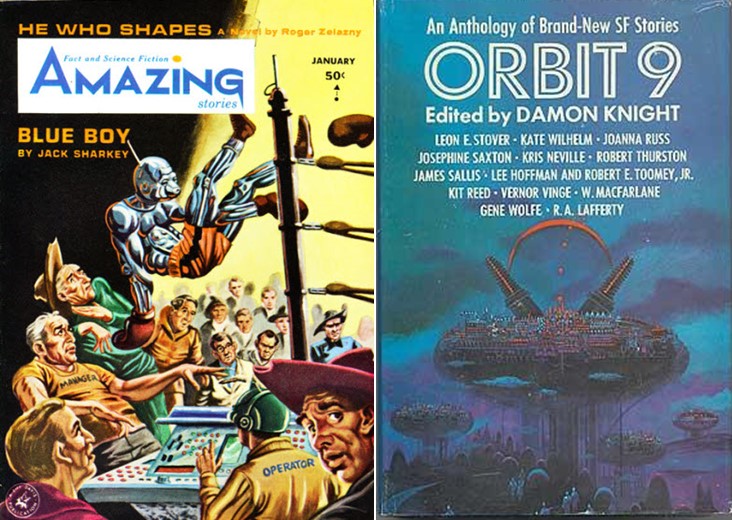

Orbit 9 by Paul Lehr

The Infinity Box was originally published in Orbit 9, edited by Damon Knight and published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons in October, 1971. It was nominated for the Nebula Award.

Much as Zelazny introduced Render in a sequence which isn’t the focus of He Who Shapes, so, too, does Kate Wilhelm introduce Eddie Laslow in what turns out to be tangential to the story. The Eddie we first see, extremely busy, devoted husband to wife Janet, working with partner Lenny to develop medical technology to help people like Mike Bronson, who needs stimulation to his muscles so they don’t atrophy while he is recovering from an accident. Eddie seems like a pretty good guy.

Eddie and Janet’s daughter wakes up screaming for no reason in the middle of the night and shortly after that, Eddie has a nightmare in which he is endlessly falling. Although they seem like isolated events, their proximity in the story links them together and their importance will only be revealed later.

The façade that Eddie is a hero begins to break down for the reader after Eddie and Janet learn that a woman has moved into their neighbor’s house. They live on a secluded road with a handful of houses. All the owners know each other, and apparently their friends, the Donlevys, have rented their house out to Christine Warneke while they are living in Europe.

Although they initially hit it off with Christine, Eddie feels there is something a little bit “off” about her and early in their friendship he and Janet push to hear her story, even as they claim they are giving her the time and space she needs. She tells them she was married to a Nobel Prize winning psychologist named Karl Rudeman. Rudeman had begun by treating her for schizophrenia, among other issues, and eventually married her. Following his death, Christine continued to live with his daughter, until Rudeman’s son-in-law made a pass at her, at which time she moved into the Donlevys’ home.

Although Eddie tells Janet that he has decided something about Christine makes him uncomfortable, he has also developed an unhealthy infatuation with her, seeing her in sexual terms, which are highlighted by Wilhelm’s descriptions of Christine’s physical presence. He also begins to fantasize about having sex with her. We also learn that the falling nightmare, which has been repeated, is a gateway to give Eddie access to Christine’s psyche, which he begins to use to attempt to control her and spy on her in private moments, exacerbating his own sexual thoughts of her.

Eddie’s mental control of Christine amounts to rape, forcing her to do things against her own will. The fact that some of those actions are sexual in nature reinforces that fact that his control is a form of mental rape. Eddie is not shown as remorseful for his actions, instead wondering if Rudeman had a similar type of control over Christine, and his own need to continue to infiltrate her mind, even as he wants to spend less time in her physical presence.

Even as his obsession with her becomes more engrossing, Eddie learns more about Christine, and comes to realize her mental state is more broken than he had originally realized. However, it is his own mental state that degenerates as his discoveries lead to jealousy and paranoia. His sense of ownership of Christine isolates him from those who love him, Janet, his kids, and Lenny, as well as those who could help him build his business.

Christine, also aware of the intrusion, believe it is Rudeman trying to control her from beyond the grave and she matches Eddie in a descent into madness, although both handle it in different ways. Because Eddie is written as the protagonist, the reader is meant to identify with him. Despite the horrors that he perpetrates on Christine, and the fact that he has brought many of his troubles on himself, the reader attempts to make excuses, even while realizing that he is not the paragon he is first depicted as.

Both of these stories deal with psychiatric patients who have questionable relationships with their therapists, whether Render’s desire for Shallott or Rudeman marrying his patient, Christine, made worse by Eddie’s obsession with Christine. Both stories offer a love triangle, although both the triangle between Render, DeVille, and Shallott and between Eddie, Janet, and Christine (or possibly Eddie, Rudeman, and Christine) take a back seat to the psychological horror both stories paint.

The cover for The Infinity Box was painted by Royo. The cover for He Who Shapes was painted by Wayne Barlowe.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.