Ahoy, Matey! Plunge the Depths of The Great Eastern by Howard A. Rodman

|

|

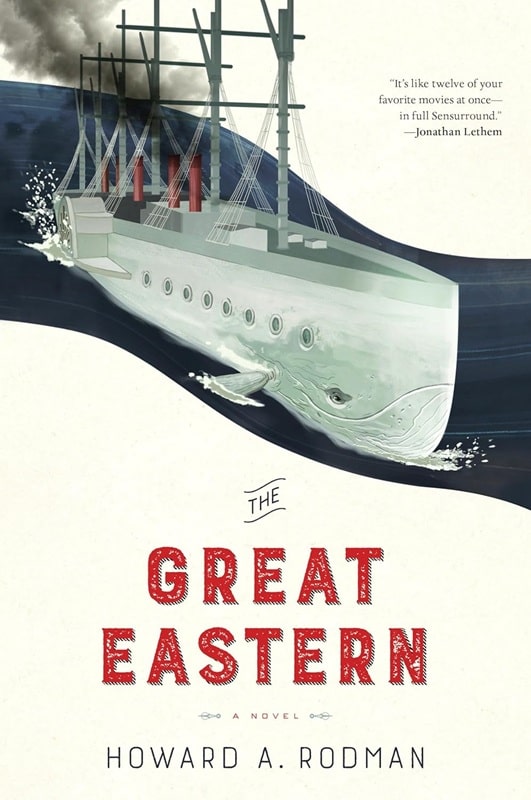

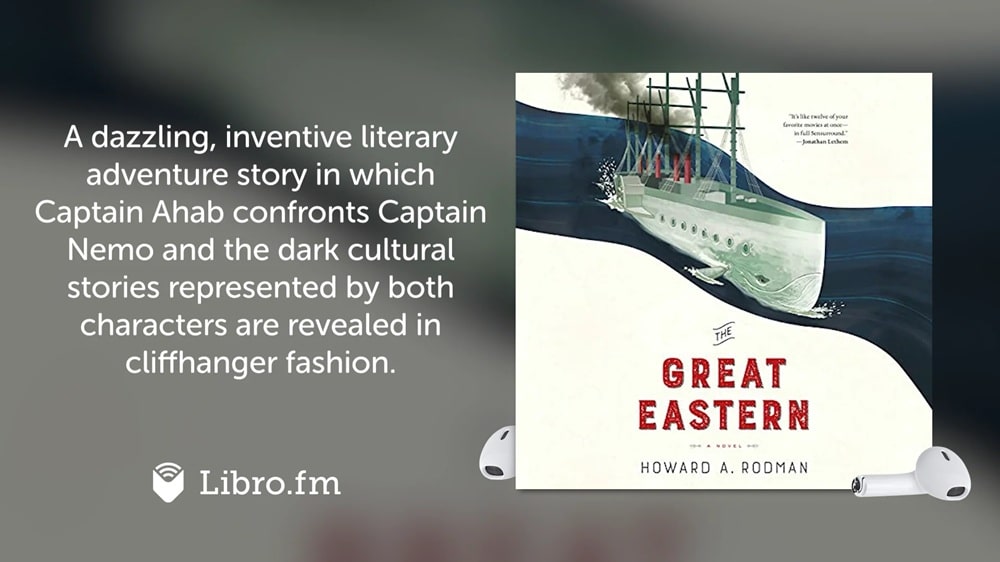

The Great Eastern by Howard A. Rodman (Melville House, June 4, 2019). Cover artist unknown

Pop quiz. What do Captain Ahab, Captain Nemo, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel share in common? Okay, if you don’t know the first two, you have no business reading anything here at Black Gate. But you are forgiven if you haven’t a clue as to Brunel. I know I didn’t until I read Howard A. Rodman’s wonderfully inventive novel, The Great Eastern.

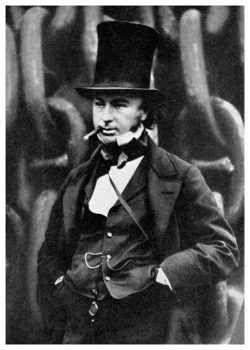

Let’s look first at the main difference. Captain Ahab and Nemo are fictional. Brunel was a real person, and not just any person, but a renowned 19th century engineer who not only worked on Britain’s the Great Western Railway and Clifton Suspension Bridge, but also designed a series of of steamships called the Great Britain, the Great Western, and the Great Eastern.

So you can start to see where this is going.

Like Ahab and Nemo, the Great Eastern‘s design suffered from significant hubris. It was the largest steamship of its time; the problem was that there wasn’t a dock large enough to accommodate it. And it ran into a series of problems, including an explosion during its first sea trial as well as the opening of the Suez Canal, which virtually eliminated the need for a steamship of its size capable of long distance voyages without need to refuel. To add insult to injury, the ship was eventually sold for use to lay the first telegraph connection across the Atlantic.

Rodman takes these actual events and extrapolates a fish tale of existential conflict between the forces of scientific modernism (Brunel), religious dogmatism (Ahab), and anti-colonialism (Nemo), with all three sharing clinical obsessive behavior defying common sensibilities.

Brunel in fact suffered a stroke (generally attributed as the result of a heavy smoking habit) while testing the Great Eastern’s engines before its maiden voyage; he died ten days later. In Rodman’s alternate universe, Brunel was dosed by agents of Captain Nemo to simulate a stroke and subsequent demise so as to be secretly whisked away to redesign and perfect the capabilities of an electrically propelled Nautilus submarine. While Nemo promises to return Brunel back to home and family once work is completed, this is delayed with the news that Brunel’s Great Eastern steamship has been sold and recommissioned to lay telegraph cable between the two industrial capitalist giants of the 19th century.

Brunel in fact suffered a stroke (generally attributed as the result of a heavy smoking habit) while testing the Great Eastern’s engines before its maiden voyage; he died ten days later. In Rodman’s alternate universe, Brunel was dosed by agents of Captain Nemo to simulate a stroke and subsequent demise so as to be secretly whisked away to redesign and perfect the capabilities of an electrically propelled Nautilus submarine. While Nemo promises to return Brunel back to home and family once work is completed, this is delayed with the news that Brunel’s Great Eastern steamship has been sold and recommissioned to lay telegraph cable between the two industrial capitalist giants of the 19th century.

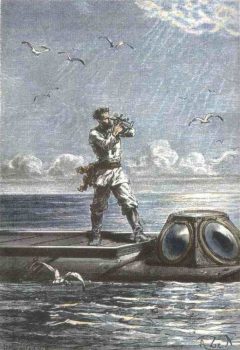

Nemo, formerly Prince Dakkar who fled to ocean life following the loss of his family during the failed 1857 Indian Rebellion against English rule, aims to scuttle the Great Eastern’s undertaking because:

If the Atlantic were no longer barrier between there and here… That would be a world in which empire would ne’er again be defeated. Worse: a world in which all habit, custom, distinction, cuisine, language, visage, sport, pleasure, devotion… Could ne’er again be sacred.

Meanwhile, Captain Ahab, despite last seen being dragged by the White Whale beneath the seas during the sinking of the Pequod, is alive and well living in Manhattan. Hearing of multiple breakages during the laying of the transatlantic cable, Ahab offers his protective services, “knowing” that the cause was not pointed rocks or other underwater obstacles, but rather the hated Leviathan foe that still carries the sting of Ahab’s harpoon.

Meanwhile, Captain Ahab, despite last seen being dragged by the White Whale beneath the seas during the sinking of the Pequod, is alive and well living in Manhattan. Hearing of multiple breakages during the laying of the transatlantic cable, Ahab offers his protective services, “knowing” that the cause was not pointed rocks or other underwater obstacles, but rather the hated Leviathan foe that still carries the sting of Ahab’s harpoon.

Why Leviathan he think, this be eel! This be coelacanth! Morsel of the maw. And so without regard for the this or for that yer Leviathan swan toward — And when the eel be within reach, raised his lower jaw, clamping down. And the piece of jaw what hit the eel first, why that would be the most protruding tooth: in this case, by history now we know the tooth of iron! The harpoon tooth! The ferrous dentition that near-killed Leviathan, but was now fully part of him!… What Ahab has given soul and leg to do. first time round, must now be done again, and with finality. ‘Til one or both were dead.

But there is no white whale, or rather the white whale has become the ironclad symbols of modernity, both the Nautilus submarine and the behemoth transatlantic cable laying steamship the Great Eastern. Which the God-fearing Ahab, who refuses to set sail on any ship not made of wood, is bent on defeating.

The fate of these three characters, and the fate of the Great Eastern itself, is a parable of progress, of human ingenuity oftentimes hobbled by hubris and fragility. And if that sounds too much like an English Lit assignment, it’s also a great fun read.

David Soyka is one of the founding bloggers at Black Gate. He’s written over 200 articles for us since 2008. His most recent was a combined review of Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix and Starling House by Alix E. Harrow.

How appropriate that this came out from Melville House.

About 20 years ago I discovered a book on The Great Eastern and was briefly obsessed with the ship. Like so many other engineering and architectural achievements of its era it staggers the imagination and makes all modern accomplishments, especially those after the Apollo missions, seem so puny by comparison.

The book seems to be getting good reviews and I’m a sucker for anything Captain Nemo related but October is fast approaching and I’m already knee-deep in ghost stories. I’ll keep it in mind for this winter.

As someone who lives in Bristol where there are hundreds of landmarks, streets, and pubs named after Brunel, the fact that someone may be forgiven for not knowing who he is blows my mind.

The image of Mr. Brunel that is included is one of my favorite historical photos. He is standing in front of the chains needed to drag the Great Eastern out of its dock and into the water. The original photo is part of the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in Manhattan. Awe-inspiring.

[…] My review of Howard Rodman’s wonderful novel, The Great Eastern is up at BlackGate. […]