Houses of Ill Repute: Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix and Starling House by Alix E. Harrow

|

|

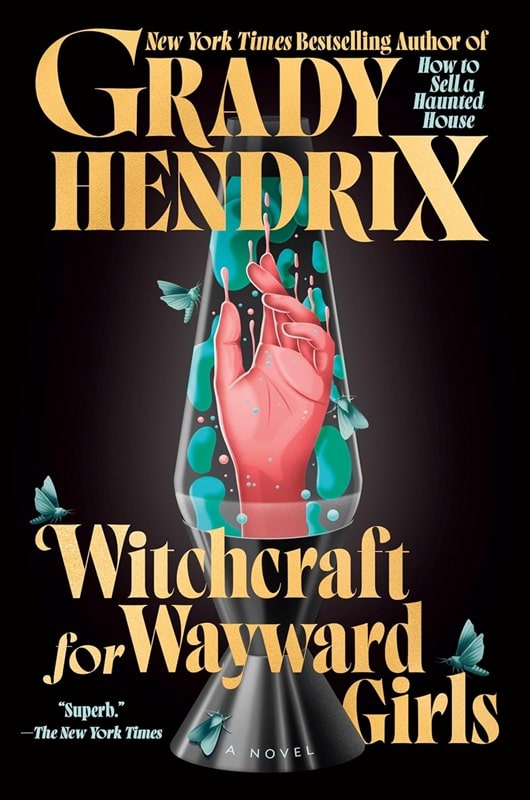

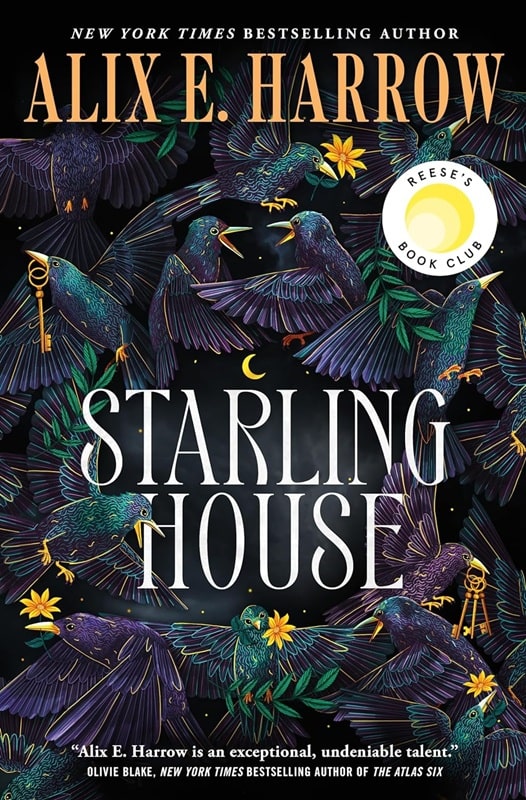

Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix (Berkley, January 14, 2025) and

Starling House by Alix E. Harrow (Tor Books, October 3, 2023). Covers: uncredited, Micaela Alcaino

No, not that kind of house of ill repute (though I confess I thought the semi-salacious implication of the headline might get some of you to read a bit further, though of course not you who are reading this now, just all those others). Rather the gothic trope of the creepy house, the mansion where ancestral secrets lie, where bad things happen. From The House of Seven Gables to The Fall of the House of Usher to Wuthering Heights to more contemporary (all the more so because they actually existed) houses of horror such as Colson Whitehead’s Nickel Academy and Tananarive Due’s Dozier School of Boys, these are places that present a facade of safety, but are far from it.

That’s the kind of house found in Grady Hendrix’s Witchcraft for Wayward Girls. Don’t be put off by the middle school YA sounding title. Homes for “wayward girls” actually existed in mid-20th century Florida. It was where unmarried pregnant teenagers were sent to have their babies, give them up for adoption, and then return to “normal” life with their and their family’s “reputations” intact.

The adolescent pregnant girls, literally abandoned by their parents for committing a sexual and “moral” offense (to my knowledge, there were no homes for boys who fathered out-of-wedlock babies and put the mothers in this position) became subject to “we know what’s best for you” treatment and holier-than-thou attitudes. In all too many cases, preserving the girl’s good name and future marriageability provided cover for the lucrative practice of selling newborns to adoptive parents on top of charging parents for room and board and, above all, discretion.

As Hendrix points out in an afterword,

Most homes confined their girls to the property… [some] forbade the use of makeup, censored the girls’ mail, charged them extra for dessert, and refused to allow them any communication with the outside world…Girls who changed their minds about adoption and tried to keep their babies would be subject to a tactic a tactic informally known as “The Bill.” At the last minute, a caseworker or staff member would inform the girl that her accumulated charges had to be paid before she could go home with their child. The Bill was usually so high that a girl had no hope of paying and so, whether she wanted to or not, she had to allow her baby to be put up for adoption.

This kind of house already earns its horrific bona fides without need of supernatural intervention (indeed, Hendrix says the first two drafts didn’t contain any fantastical elements). Adding witchcraft, however, layers a metaphor for women’s empowerment, albeit one that carries a price, that is closely associated in folklore with childbirth. As Hendrix notes,

There’s a popular [though discredited] myth that the Catholic Church targeted midwives as witches… In fairy tales, witches are constantly eating or stealing babies. In the fevered popular imagination, witches crown their black sabbaths with a child sacrifice.

The story centers on Fern (all the girls are given an arbitrary plant-based pseudonym during their stays, ostensibly to preserve privacy, but actually to depersonalize them), a 15 year old in effect kidnapped by her father to endure her pregnancy at the Wellwood House in St. Augustine, Florida in the summer of 1970. Her situation is not, needless to say, a happy one.

No one would write, no one would call, no one outside this house even knew where she was, except her dad, and he hated her. She never felt more alone. She would do whatever they wanted her to say, eat whatever they told he to ear, just so long as they let her of back to the way thing were before.

The smart-assed (if ultimately superficial) hippie-styled resistance of a fellow wayward girl provides some hope of eventual escape from the home’s adult “benefactors.” But it is a bookmobile librarian who hands Fern a tome entitled How to be a Groovy Witch that leads to the invocation of witchcraft to avenge mistreatment.

Unfortunately, to paraphrase Peter Parker, with great power comes unexpected consequences and questions of responsibility. And just as it’s one thing to proclaim hippie slogans and quite another to actually adhere to them in the real world, practicing witchcraft also comes with significant moral compromises. Which Fern must balance against the familial and social stigma of unwed pregnancy, of being forced to give birth and then relinquish her child. As once of the wayward girls now an adult and long after giving up her baby puts it:

There’s a part of me that’ll always be seventeen. A part of me that’ll be seventeen forever, locked away in that Home, cut off from the world.

That’s a house you can run away from, but never escape.

Locked away and cut off from the world is also the predicament in Alix E. Harrow’s The Starling House. Instead of the proverbial madwoman in the attic, it’s a male recluse in the titular creepy home containing disturbing secrets. Another kind of forced habitation is the stifling town, the ironically named Eden, Kentucky, modeled somewhat after the equally ironically named and actual Paradise, Kentucky immortalized in the John Prine song about a family-owned coal company that exploits the land and resident workers. It’s a place Kentucky native Harrow knows as “a place of very mixed experiences that I love very, very, very much, and which has just an incredible violence and terror to it.”

Our heroine, Opal, is a social malcontent and for the most part first-person narrator (there are also point of view shifts and even footnotes and a bibliography!), a high school dropout working a dead-end job in a dead end town. Orphaned following her mother’s death in a car crash, she is trying to save up money to send younger brother Jasper to a private school and get a better life out of Eden. But kind of hard to do on a Tractor Supply cashier’s salary and some petty larceny.

Walking to work, Opal finds herself strangely (of course) drawn to the ancestral home of the Starling family, one of whom wrote a dark fantasy for children called The Underland (the book’s illustrations appear throughout) and disappeared under, of course, mysterious circumstances. Part of the house’s appeal to Opal is how the shapes on the front gate remind her of the creatures depicted in The Underland.

The gates of Starling House don’t look like much from a distance — just a dense tangle of metal half-eaten by rust and ivy, held shut by a padlock so large it almost feels rude — but up close you can make out individual shapes: clawed feet and legs with too many joints, scaled backs and mouths full of teeth, heads with empty holes for eyes.

Opal feels compelled to look inside the old neglected house, managing to convince the current Warden, Arthur Starling, despite his initial misgivings, to hire her as a housekeeper. Opal soon discovers a special strange connection to the equally strange house. And to Arthur.

Sinister forces soon intercede, however. The aptly named Gravely Power company wants to acquire the Starling House property by means fair or foul. And then there are supernatural entities literally right out of The Underling. All of which jeopardize Opal’s already problematic relationship with Arthur.

The Starling House has rooms for just about everything — Southern gothic horror, classic fairy tale, corporate evil, environmental and class issues, a love story even (it’s not coincidental that Harrow makes a point of mentioning in the Acknowledgement that her mother “read every version of Beauty and the Beast with me”), all wrapped together in a single, ahem, attractive property. It’ll particularly resonate with anyone who grew up in a small town or boring subdivision who tried to run away from the horror of humdrum existence.

David Soyka is one of the founding bloggers at Black Gate. He’s written over 200 articles for us since 2008. His most recent was a review of The Bright Sword by Lev Grossman.