A Hearty Library of Genre Fiction: The Arbor House Treasuries edited by Martin H. Greenberg, Bill Pronzini, Robert Silverberg, and Others

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

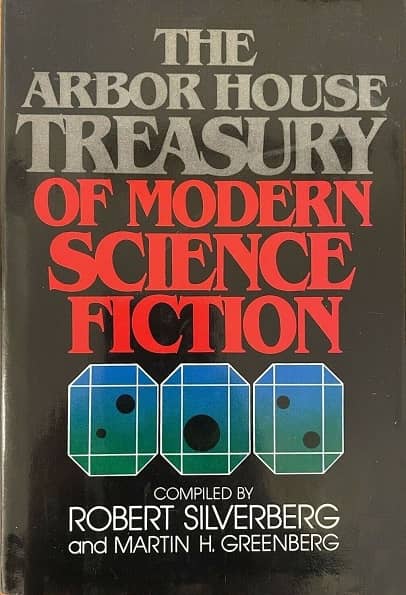

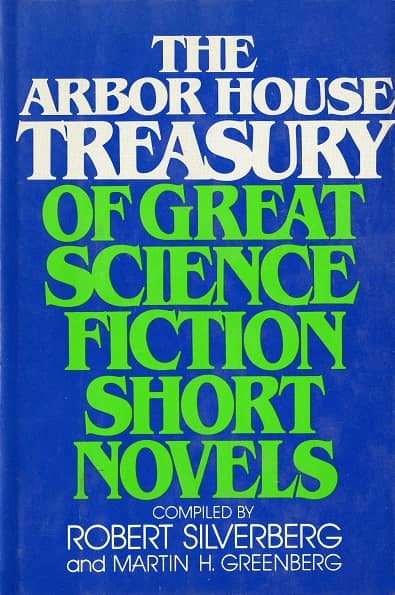

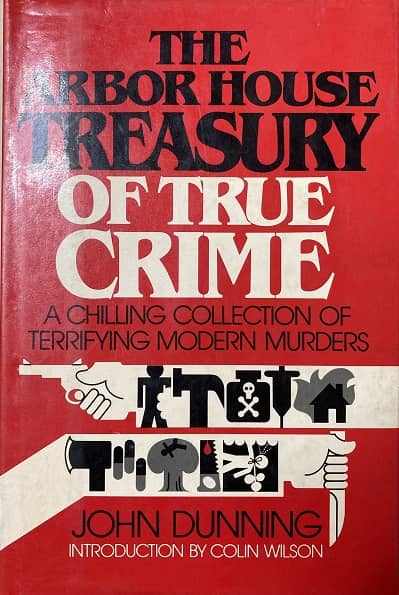

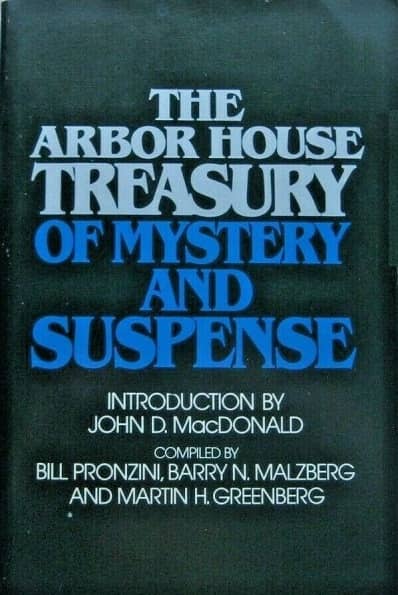

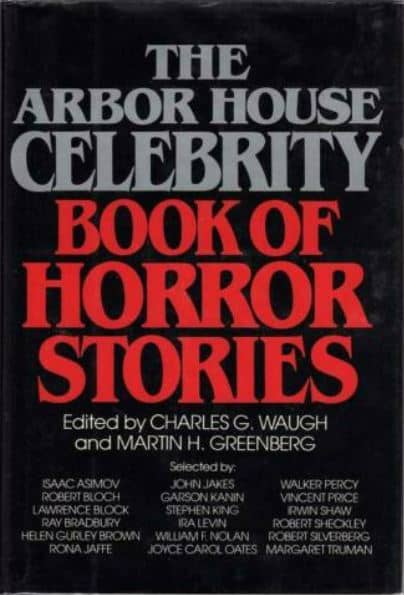

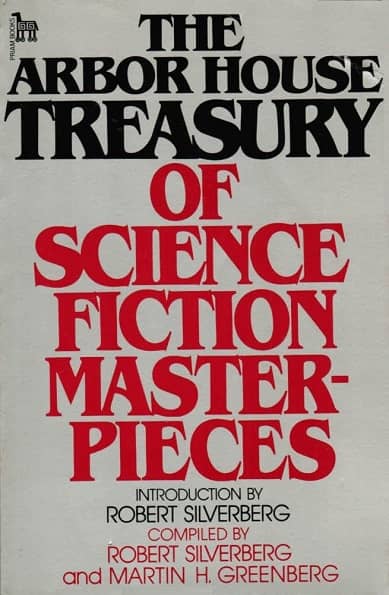

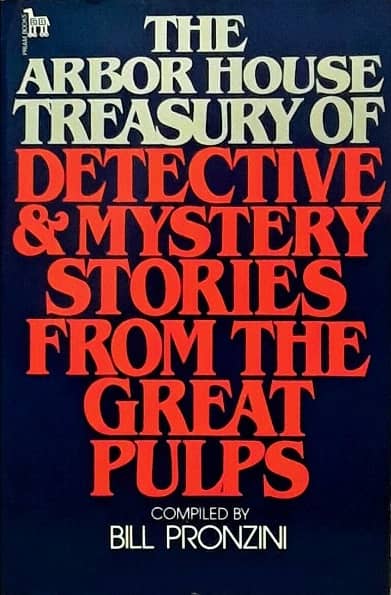

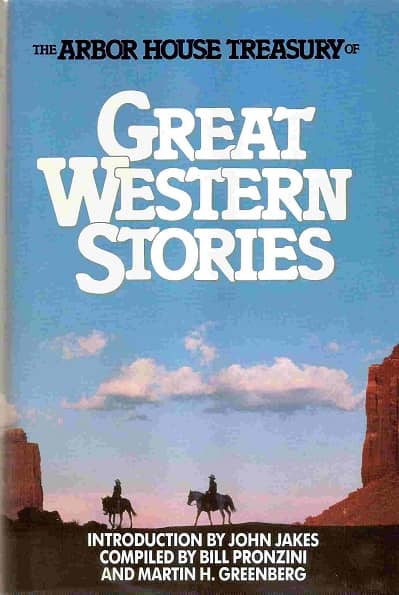

The Arbor House library. Cover designs by Antler & Baldwin, Inc.

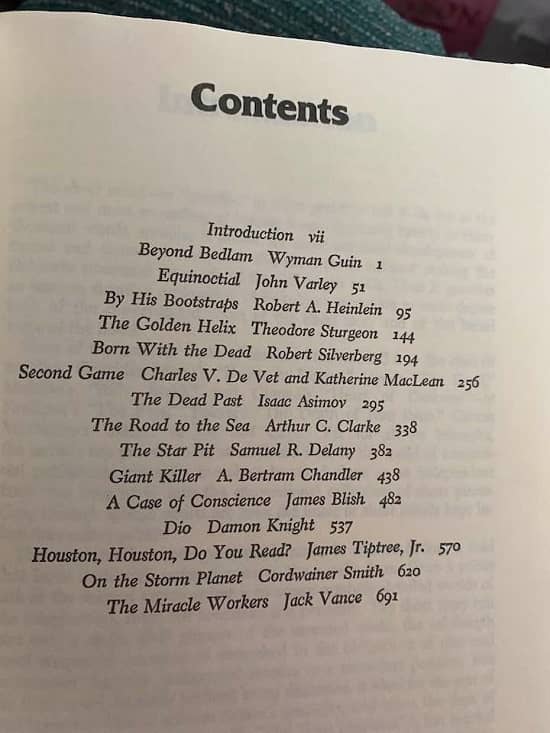

Last week I ordered a copy of The Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels, a thick anthology from 1980 edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Robert Silverberg, and when it arrived I was astounded by the rich assortment of treasures within. Novellas both classic and long overlooked (even by 1980), including “By His Bootstraps” by Robert A. Heinlein, “The Golden Helix” by Theodore Sturgeon, “Born With the Dead” by Robert Silverberg, “The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany, “Giant Killer” by A. Bertram Chandler, “A Case of Conscience” by James Blish, “Houston, Houston, Do You Read?” by James Tiptree, Jr, “On the Storm Planet” by Cordwainer Smith, “The Miracle Workers” by Jack Vance, and many more.

It made me wonder how I’d managed to miss this book for four decades, and sparked an interest in other Arbor House Treasuries. I knew there were a couple others… a mystery volume, and one on noir, or something? Twenty minutes on Amazon, eBay, and ISFDB (my research triumvirate these days) yielded at lot more than I thought — no less than eleven. I keep hoping a little more digging will yield a clean dozen.

The (very) impressive contents of The Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels

The Arbor House Treasuries were published between 1980 and 1985 and covered a wide range of genre fiction, including SF, Horror, Detective, True Crime, and Westerns. They were compiled by a round-robin team of some of the most experienced editors in the field, including Martin H. Greenberg (8 volumes), Bill Pronzini (5), Robert Silverberg (3), Barry Malzberg (2), Charles G. Waugh (2), and John Dunning (who?) with one.

The books were published in library-friendly hardcover and big, beefy trade paperback editions, and while their cover designs could best be described as serviceable, they look very handsome side-by-side on your bookshelf.

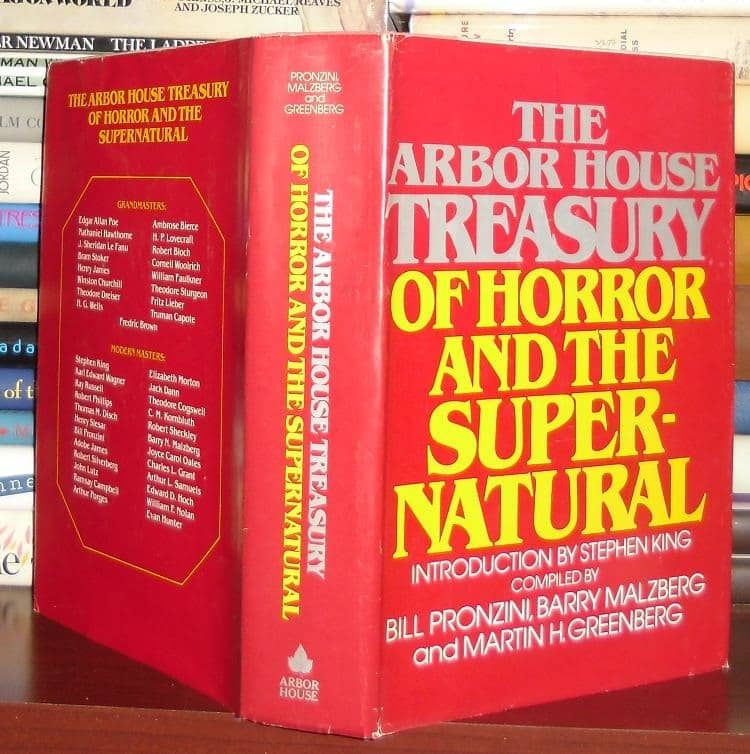

The Arbor House Treasury of Horror and the Supernatural (1981), all 599 fat pages

The complete set contains a lifetime of reading (certainly at the pace I’m making my way through them, anyway), and would be the foundation for a robust library of genre fiction.

Here’s the complete details, in order of publication.

The Arbor House Treasury of Modern Science Fiction, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Robert Silverberg (766 pages, $19.95 hardcover/$8.95 trade paperback, April 1980)

The Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Robert Silverberg (778 pages, $19.95 hardcover/$9.95 trade paperback, November 1980)

The Arbor House Treasury of True Crime, edited by John Dunning (476 pages, hardcover, January 1, 1981)

The Arbor House Treasury of Horror and the Supernatural, edited by Martin H. Greenberg, Barry N. Malzberg and Bill Pronzini (599 pages, $19.95 hardcover/$8.95 trade paperback, May 1981)

The Arbor House Treasury of Mystery and Suspense, edited by by Bill Pronzini, Barry N. Malzberg, and Martin H. Greenberg (607 pages, hardcover, January 1, 1982)

The Arbor House Celebrity Book of Horror Stories, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh (448 pages, $20.95 hardcover/$9.95 trade paperback, 1982)

The Arbor House Treasury of Nobel Prize Winners, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh (319 pages, 1983)

The Arbor House Treasury of Science Fiction Masterpieces, edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Robert Silverberg (538 pages, March 1, 1983)

Arbor House Treasury of Detective and Mystery Stories from the Great Pulps, edited by Bill Pronzini (342 pages, hardcover and trade paperback, June 1, 1983)

The Arbor House Treasury of Great Western Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin Harry Greenberg (455 pages, May 1, 1985)

The sparse covers were by Antler & Baldwin, Inc.

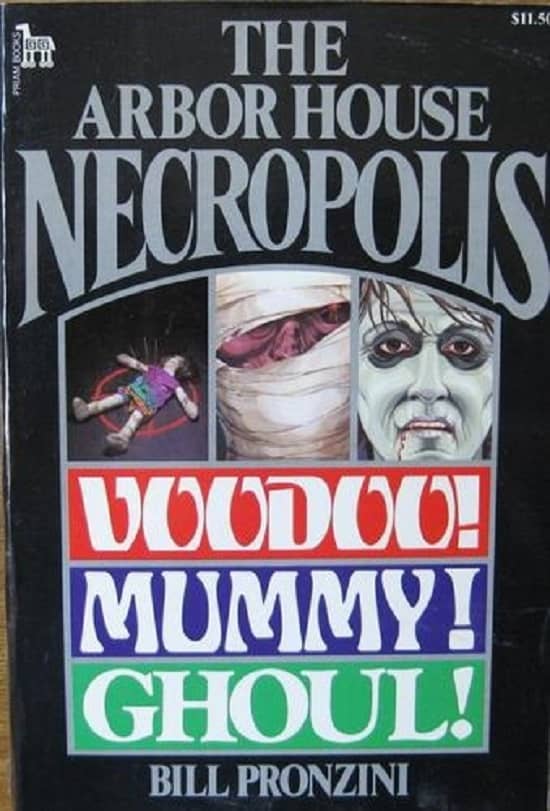

The Arbor House Necropolis, a compilation of three scary Pronzini anthologies

Bill Pronzini published one additional volume in 1981, The Arbor House Necropolis, an omnibus of three of his anthologies: Voodoo! (1980), Mummy! (1980), and the unpublished Ghoul! He provided a separate introduction for each.

Here’s the complete details.

The Arbor House Necropolis edited by Bill Pronzini (725 pages, $11.50 in hardcover and trade paperback, November 1981)

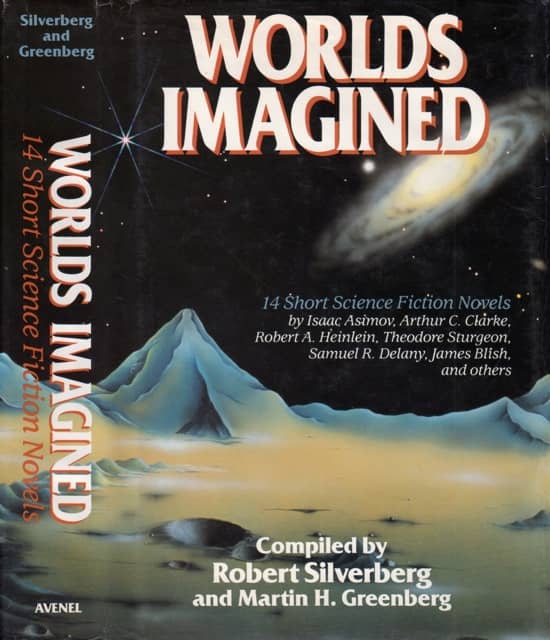

Many of these books enjoyed a long life on bookstore shelves, thanks to constant repackaging by numerous publishers over the years. So The Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels became Worlds Imagined from Avenel Books in 1989, The Arbor House Treasury of Science Fiction Masterpieces was reprinted as Great Tales of Science Fiction by Galahad Books in 1985, and on and on.

Worlds Imagined (Avenel Books), a repackaging of

The Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels

Many volumes were retitled more than once. The Arbor House Treasury of Horror and the Supernatural, originally released in 1981, was repackaged no less than four times over the next three decades, as:

1985 – Great Tales of Horror & the Supernatural (Galahad Books)

1991 – Classic Tales of Horror and the Supernatural (Quill / William Morrow)

1991 – The Giant Book of Horror Stories (Magpie Books, UK)

2010 – Masters of Horror & the Supernatural: The Great Tales (Bristol Park Books)

I’ll be digging into a few of these books in more detail over the coming months, starting with Great Science Fiction Short Novels, a delightful volume that still makes fantastic reading today.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

I’ve had the first one on your list, picked up not long after it was published. I’ve dipped into it a few times over the years, always with much enjoyment. I had no idea there were others in the same format. Thanks, John!!

You’re welcome, as always, Smitty. I’ll be digging into them in more detail in coming weeks. I’m very interested to compare the contents of these two volumes, both edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Robert Silverberg.

The Arbor House Treasury of Modern Science Fiction

The Arbor House Treasury of Science Fiction Masterpieces

John Dunning (1918-1990) was an American true crime writer who wrote at least a dozen books to on the subject.

I immediately thought he was the same John Dunning who has written multiple acclaimed mystery novels, but was sternly (and belatedly) admonished by Wikipedia not to confuse the two different authors.

LOL. At least you’d heard of him!

The only one I bought when it came out was Horror & the Supernatural (Pronzini, Malzberg & Greenberg), but I ordered Modern Science Fiction a few years ago. It makes a great companion volume to The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One, also edited by Silverbob. I can’t see any overlap between the two.

Piet — I believe you’re correct. I can’t see any duplication either, and they’re both fantastic anthologies.

Here’s the TOC for The Arbor House Treasury of Modern Science Fiction:

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?35286

And here’s The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One:

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?29109

I’ll look at the individual Arbor House volumes in more detail in upcoming VINTAGE TREASURES posts.

I know of at least one more, that will give you your even dozen: The Arbor House Celebrity Book of the Greatest Stories Ever Told / Compiled by Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh, 1983. Don’t know if there were any more.

Brian,

Right you are! An excellent catch, and it does indeed bring the count up to an even dozen. I could have added another full row to that delightful bingo chart at the top of the page. 🙂

This one looks like it was released in 1983. Not a lot of copies on eBay, but Amazon will sell you a used paperback for under 5 bucks. Might make a decent addition to my fast-growing set.

Thanks for the tip!!

An impressive effort on John Dunning’s part. A 476 page true crime anthology of quite some considerable merit.

Dunning has a flair for gentler humour in a genre not known for any humour at all, true crime, e.g. ‘The police are a very democratic organisation, both sergeants and inspectors can make mistakes.’ More off-beat than the literary equivalent of ‘prat falls’. There are many, many other instances of a clever and subtle humour.

One of the defining characteristics of the short form, as adopted here, is a reliance on driven plot to engage the reader even so Dunning uses adverbs and adjectives among a number of strategies, liberally and to good effect.

He also has a flair for compact descriptive passages, e.g. ‘The body lay at the foot of a deep slope on its back, the limbs extended like starfish, and the head no more than a shattered mass of splintered bones, torn flesh, extruded brain and black, dried blood, from which one dull, sightless and pocketless eye glared hideously.’ Page 210 There are many examples of this caliber of writing.

Although published in the late 1970s there is a nod towards the cinematic which has become much more prevalent in recent years, e.g. many of Stephen Kings works seem designed in part to roll over into movies. An example from Dunnings pen, reads, ‘The bed cover still clenched in her fists, Ingrid Riedel put back her head and screamed and screamed and screamed.’ Page 194

All are paint patches on Dunnings’ palette. He dabbles, for instance, in philosophy, Page 116, lit criticism Page 178, and police procedural mechanisms, everywhere! He is loyal to his genre i.e. true crime e.g. ‘Sprawled on the living room floor, her half naked body surrounded by torn shreds of her clothing Monique Gaumer lay dead with a 9mm bullet fired at close range through the brain.’ Page 96 As evidenced in this brief quote the necessary tropes are included – sex, a particular ’70s view of women, violence, a level of technical expertise and uncluttered, plot driven writing.

There are traces of the ’70s crime milieu dripping from every page. I am reminded of The Sweeney by way of comparison. The Sweeney was a cracker jack British crime series which aired from 1975 to 1978. There was a gritty testosterone driven realism to the fictional show and there’s a gritty realism to this testosterone driven nonfictional anthology. Just one of many instances, but we find on Page 96 that all of the hostages are killed, even the child. It makes for a brutal reality and compulsive reading about a terrifying episode.

Dunning makes the distinction between fiction and nonfiction quite clearly on Page 117 when he observes that, ‘In a novel … However this, was real life and real death.’ He makes the distinction between recording what actually happened and what an author might like to happen. He speaks directly to the reader in this particular instance but makes the same point again but in a more nuanced manner elsewhwere.

Some specific stories: Chapter 26 Daddies Girl. This is a story of incest and murder. Incest is one of Dunning’s central concerns. Events take place in Melbourne and Geelong. Apart from some mentions to Russel St it could in fact be set anywhere. There is nothing to root this story in either Melbourne nor Geelong. The actual setting is quite sterile. Dunning would have it that Melbourne and Geelong are 50 miles apart. They are 70 miles apart. I can find no external reference to this crime. Dunning can create sense of place though e.g. providing hay for freezing deer in a German National Park.

Chapter 7 A Family Affair. Is explicitly about incest. Dunning deals with it in an almost clinical manner. This clinical approach is supported by a sort of detached coyness.

Chapter 23 Peculiar Madness. This is by far the most unambiguous take on violence. Named body parts described and nailed to the wall, incisions following the vaginal / uterine track and much, much more.

Chapter 28 The Liberation of Penny Potterton. Is it true … well? Is it good? Absolutely. This is quite possibly one of the best, if not the best, short stories that I have so far encountered. A vengeful mother justly takes the life of her daughters evil boyfriend in quite a macabre manner. It is so very much more than this one sentence gloss.

Dunning seems not interested in gratuitous sex nor violence. If they aren’t a predominate aspect of a given crime then they don’t dominate the crime’s description. Even though this might be the case there is a lot of sex and a lot of violence. None more so than the final narrative of the collection, Chapter 30 Little Girl Stew.

Most stories are set in a) Germany. (By far the most.), b) Europe, c) Other e.g. Australia, New Zealand and so on.

There is so very much which is positive that could be said of The Arbor Treasury of True Crime. I read 500 pages in 3 days. For me that says a lot.

A fabulous review, reverend! Have you read any of the others? Love to hear your thoughts.