Here Comes Everybody: Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner

|

|

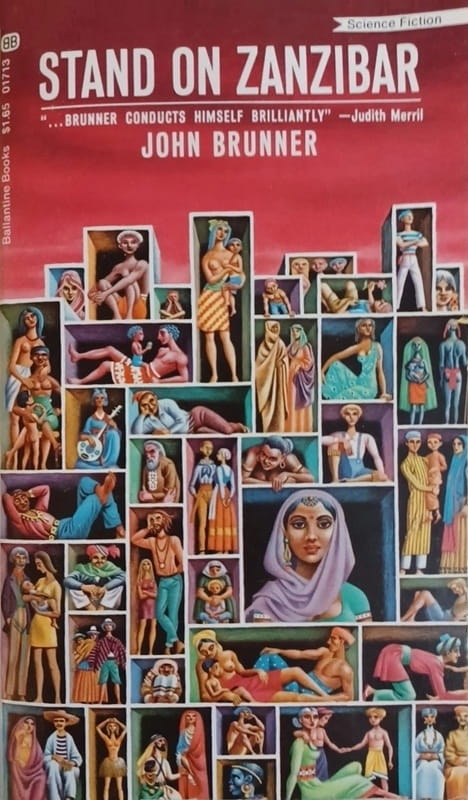

Stand on Zanzibar (Del Rey/Ballantine, June 1976). Cover by Murray Tinkelman

Watching their sets in a kind of trance

Were people in Mexico, people in France.

They don’t chase Jones but their dreams are the same—

Mr. and Mrs. Everywhere, that’s the right name!

Herr und Frau Uberall or les Partout,

A gadget on the set makes them look like you.

Stand on Zanzibar is perhaps John Brunner’s most significant novel. Up until then, he had written competent science fiction on familiar themes such as psionics (Telepathist) and time travel (The Productions of Time). With Stand on Zanzibar he began writing larger books that were no longer purely ways of playing with such standard ideas, but examinations of our own world in a fantastic mirror. At the same time, they used a more sophisticated literary method — not the surrealism that inspired much of the New Wave, but a naturalism similar to nineteenth-century fiction.

[Click the images to populate larger versions.]

The title Stand on Zanzibar alludes to this book’s central theme: population. A very early chapter, “The Happening World (1),” offers the proposition that for a particular hypothetical area, the entire human race could stand on the land area of Zanzibar. I worked it out and got 8.92 billion as the total human population — impressively close to the current world population, for a novel published in 1968 (not that science fiction is meant to be prophecy, but this was the first of many striking anticipations of our present world).

My copy, a mass market paperback, has a front cover blurb taken from The London Sunday Times: “A vast uncontrolled explosion of a book.” I have to dissent from that; Brunner’s novel has an elaborate formal design that is hardly ever out of control.

|

|

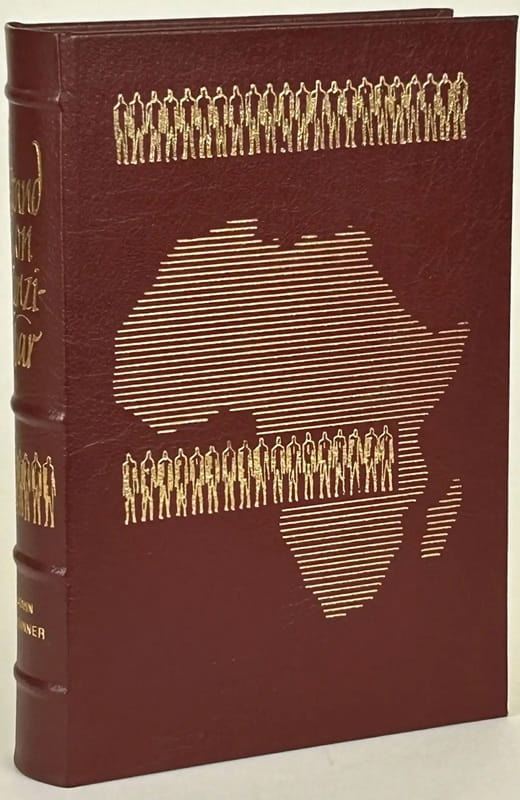

Stand on Zanzibar hardcover first edition (Doubleday, September 1968). Cover by S. A. Summit, Inc.

In the first place, it has repeated labels for four types of chapters, each having a different function in the story.

“The Happening World” is a series of items about what’s going on in the background. They’re much like the short news stories Robert Heinlein placed at the start of chapters in some of his books, but more explicitly split off. Some of them are explicitly identified as news broadcasts. This ties together four recurrent elements in Brunner’s future world: Shalmaneser, a computer with computational ability theoretically exceeding that of the human brain; Scanalyzer, a program run on Shalmaneser that analyzes the news; Engrelay Satelserv, the intercontinental network that broadcasts Scanalyzer; and Mr. and Mrs. Everywhere, animated images of television set owners that are projected into scenes in news stories.

|

|

Stand on Zanzibar (Ballantine Books, September 1969). Cover by Steele Savagen

One striking minor element in the first of these chapters is “participant breakin,” where people watching Scanalyzer can ask questions or offer corrections — another point where Brunner’s anticipated future looks strikingly like ours. (The portmanteau “Engrelay Satelserv” is typical of Brunner’s version of future English, where a lot of words have been shortened or compressed together or both.)

“Context” is a way of presenting background information about the world — an interesting one, because Brunner doesn’t use the indirect exposition that John Campbell demanded and Robert Heinlein was a master of. He just presents short nuggets, sometimes of purported fact, sometimes of cultural material. Many of these are attributed to Chad Mulligan, who functions as a kind of Greek chorus: a famous sociologist who dropped out of society after writing books with titles such as You’re an Ignorant Idiot, You, Beast, and The Hipcrime Vocab (officially classed as “subversive literature” by the U.S. Army) — another formal device. I have to say, though, that my own favorite example is a calypso song about Mr. and Mrs. Everywhere:

English Language Relay Satellite Service

Didn’t do this without any purpose.

They know very well what they would like—

A thousand million people all thinking alike.

When someone say something you don’t ask who—

A gadget on the set has it said by you!

“Tracking with Closeups” (an explicitly cinematic label) covers more conventional narrative scenes that involve secondary characters. They often appear in two or three chapters (there are 32 of these), but they have only peripheral involvement, if that, with the main story. Their function is to illustrate Brunner’s future society from different angles, giving a panoramic view of it.

James Joyce gave the protagonist of Finnegans Wake the nickname “Here Comes Everybody”: These chapters show us the everybody of Brunner’s future, the diverse human beings who participate in Mr. and Mrs. Everywhere. This kind of perspective has become more common in recent fiction — Harry Turtledove, for one, writes many novels with large casts of characters — but I have to say I like Brunner’s explicitly marking some characters as secondary; I wish the technique had caught on.

“Continuity” is the real story, and it has a complex structure of its own. It starts out with the daily lives of two men in New York, which is now under a huge dome (an element of Brunner’s future that didn’t work out). Norman Niblock House is black and is a vice president of General Technics, the megacorporation that built Shalmaneser and owns him (Shalmaneser is never referred to as “it”); Donald House is white and is secretly being paid to read the scientific literature and note significant connections, in the seeming role of a rich dilettante. The two are roommates; housing is too expensive for one person to afford alone. They are not a couple; both are clearly heterosexual, and one or the other of them will recruit a woman to share the apartment, while the two men share her affections.

|

|

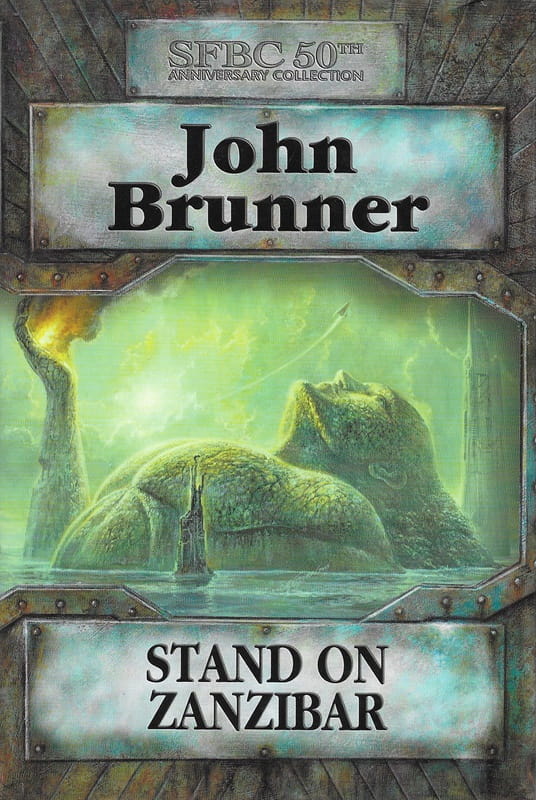

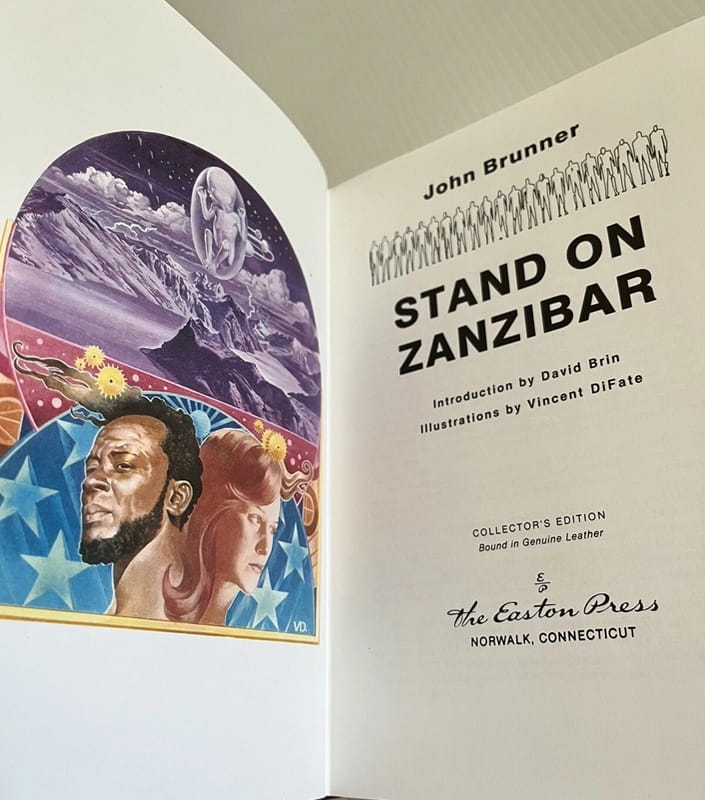

Stand on Zanzibar, Science Fiction Book Club 50th Anniversary

Collection #13 (SFBC, August 2004). Cover by Bob Eggleton

This is seemingly a common arrangement; we’re told that there are vast numbers of women who never have a place of their own, but cohabit with various men, living out of a single suitcase (perhaps made less implausible by the prevalence of disposable paper clothing). The first part of “Continuity” is something of a slice of life, but with both men being called to take more responsible roles.

Near the middle of the novel, one of these chapters is both a point of transition and a massive set piece: Guinevere Steel, the proprietor of a chain of high-fashion businesses, the Beautiques, that market a look for women that suggests the sexy robots of anime, throws a party that both Hogan and House attend. Steel is in a bad mood and decides to make it a forfeits party, with a costume theme of “the twentieth century,” and with humiliating and often cruel penalties for anyone who doesn’t adhere to the theme. (For example, one of the guests, who is wearing Nipicaps — prosthetic nipples that can be used to simulate arousal, which Steel herself brought onto the market well into the twenty-first century — is ordered to strip to the waist, revealing a hairy masculine chest.)

Another of Steel’s guests is Chad Mulligan, who has decided to come back into society after living on the streets for several years, and who gets into conversation with Hogan, House, and Elihu Masters, the U.S. ambassador to the fictitious country of Beninia. Brunner gives the reader a long series of “overheard” remarks, in effect a further miniature sketch of the twenty-first century’s culture. Then he shows the party being disrupted by a news break: The less developed country of Yatakang has announced that their brilliant scientist Dr. Sugaiguntang has created methods for upgrading human genetics — a general shock to people in a society where eugenic laws forbid reproduction to a growing share of the population, and a specific one to Hogan, who has just been ordered to go to Yatakang as an agent of the U.S. government.

|

|

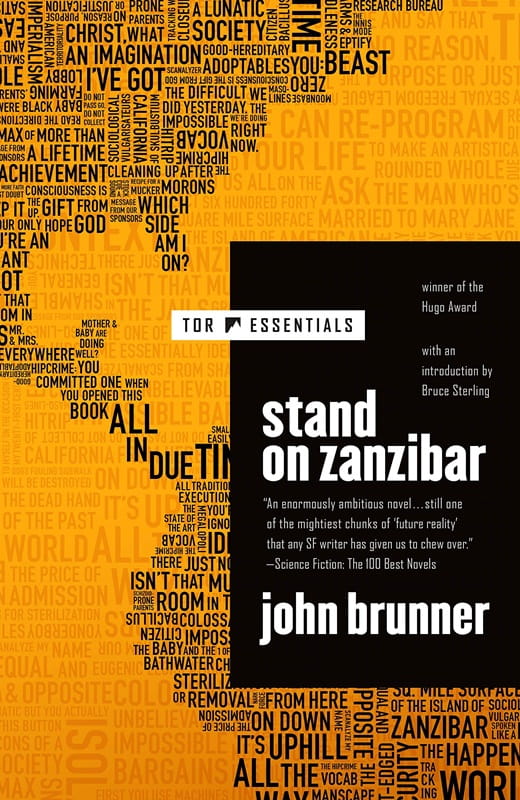

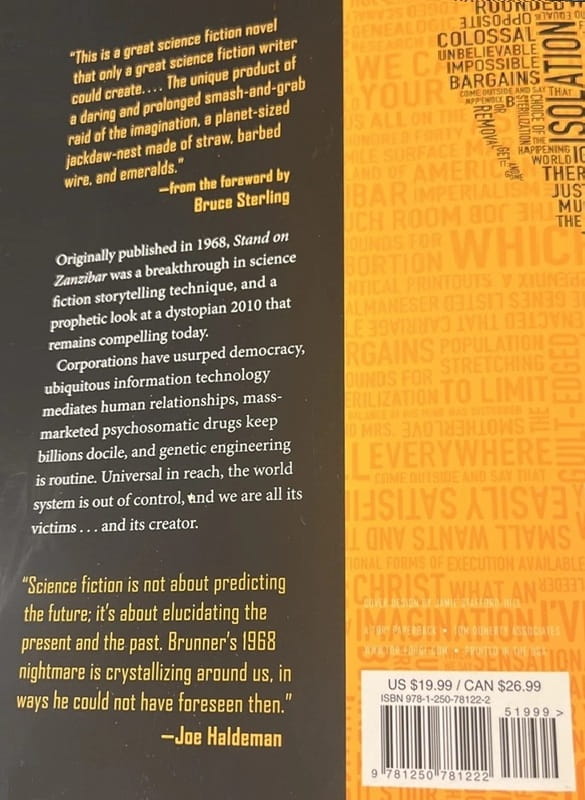

Stand on Zanzibar, Tor Essentials edition (Tor, March 23, 2021). Cover uncredited

This takes us away from New York to overseas locations. Brunner’s world has three fictitious locations: The fifty-second American state, Isola, formerly the Sulu Archipelago in the Philippines, is now a war zone. Yatakang, a former Dutch colony with a largely Muslim population, in an archipelago near Isola, seems to be modeled on Indonesia. Beninia, a former British colony, is described as lying in between RUNG (the “Republican Union of Nigeria and Ghana”) and Dahomalia (a federation of Dahomey, the Upper Volta, and Mali); it thus can’t be present-day Benin (formerly Dahomey), but appears to occupy the location of Togo, though in our history that was another French colony.

Hogan is sent on a mission to Yatakang; House is put in charge of a plan for General Technics, subsidized by the U.S. State Department, to modernize the desperately poor Beninia. They face radically different fates as a result.

Beninia, in particular, proves a challenge: Despite its poverty and military weakness, it has avoided many of the worse social problems of the world around it. General Technics planned to have Shalmaneser manage its economy — but Shalmaneser rejects descriptions of Beninia as obviously impossible!

In desperation, House arranges for Mulligan to talk with Shalmaneser, transforming him from a chorus to a kind of prophet (and Shalmaneser into a kind of god); this is the novel’s climactic scene, and brilliantly written as a display of scientific discovery, the kind that Isaac Asimov said begins with the words “That’s funny…”

Stand on Zanzibar did a monumental job of world building. All sorts of indirect consequences follow from the vast overpopulation Brunner postulates: people sleeping on the streets; eugenics laws that deny reproduction to many people; a religious cult, the Divine Daughters, sworn to celibacy; widespread toleration of homosexuality (which doesn’t produce children); the reorientation of sex from procreation to hedonism; the fading of marriage into a series of casual liaisons — and, grimly, widespread resentment of anyone who has too many children (three bring hostile reactions; a rumored five are enough to produce a murderous mob) and the prevalence of mass homicide by “muckers” (another point of correspondence to our own era). Yatakang represents one attempt to solve some of these problems; the solution of the Beninia mystery points at a different possible solution.

|

|

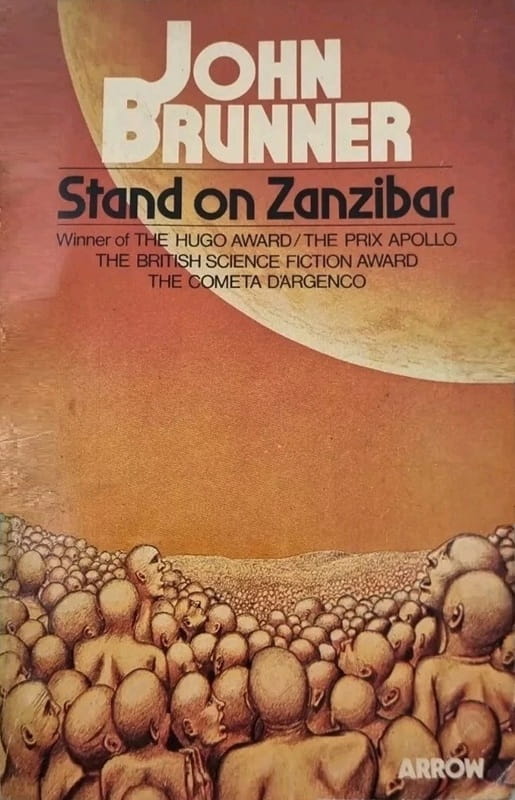

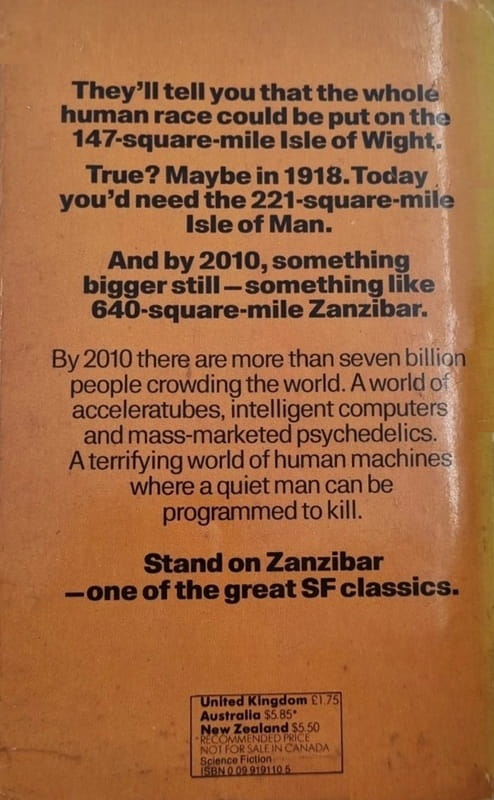

Stand on Zanzibar, first UK paperback edition (Arrow Books, 1971). Cover uncredited

Secondarily, it’s also a plausible story about the personhood of a computer, and about how difficult it is to discover. Indeed, it requires a second cognitive reversal to do so, simultaneous with the one about Beninia. And it leads to the final memorable line of the novel: the cybernetic equivalent of the phrase, “Christ, what an imagination I’ve got.”

I have to say that Brunner’s future seems internally inconsistent. He shows a long series of conditions that make for below-replacement fertility, with many people stopping at two and many more never getting there; it’s hard to see how his future United States could be dangerously overpopulated. I suppose he can’t be criticized for not thinking it through, given our own belated realization of the problems of below-replacement fertility in countries such as China and Japan.

But it shows how much his vision of the future was a product of the preoccupations of his own era. On the other hand, even if his world building makes debatable assumptions, Brunner shows us a coherent picture of its fictional world, and an impressively detailed one, for which his innovative technique was the perfect tool.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels.