Sci-Fi Dystopias We Should Learn From

|

|

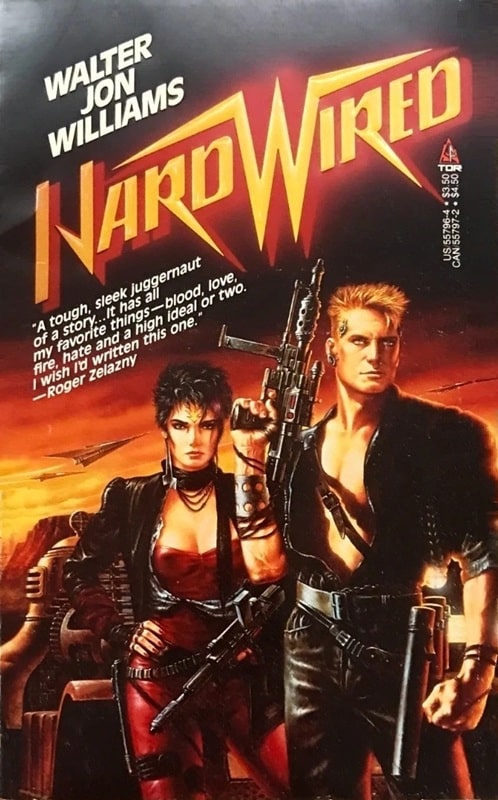

Hardwired (Tor Books, June 1986). Cover by Luis Royo

Sci-fi has long been home to nightmarish views of the future as thrilling as they are frightening. The genre simply would not be the same without our post-apocalyptic wastelands.

But for every Handmaid’s Tale there’s a dystopian vision that doesn’t get the appreciation it deserves. Some have certainly sold millions of copies but are more recognized for drama or action as opposed to what they have to say about the challenges facing us tomorrow. Here are several such examples that definitely deserve a bit more love from readers. Not for how epic or cool they are but for the underlying ideas their authors hoped we would absorb.

Hardwired by Walter Jon Williams

Hardwired is rightly celebrated for its contributions to cyberpunk. So much of the verbiage, flare, and aesthetic of the subgenre can be traced back to this relatively short novel. A future where the lines between man and machine are blurred? A ruined Earth? The illicit struggle to survive despite overwhelming odds? It’s all here, the ingredients many a choom would run with over the years.

[Click the images for utopian versions.]

With the uber-wealthy and powerful living in outer space, the rest of humanity is left to effectively scrape by on Earth. Stripped of economic power and sovereignty, the dregs of society are forced to endure lives where justice and freedom are in short supply. Technology, instead of liberating mankind, has become yet another form of oppression. Everyone seems to be out to get someone, with the only promising future being a trip beyond the atmosphere.

In addition to being a grand read, Walter Jon Williams’s most famous work has a lot to say about the future. About globalism, trafficking, and survival on the margins of society. It shares a number of characteristics with good film noir including mysterious characters and a laser-focus on the less fortunate of society.

Throughout it all, however, there are traces of the nobler aspects of human character. New honor codes to replace older ones as well as the instantly relatable fight to build a better tomorrow.

The Dreddverse

In the hands of its most skilled writers, Mega-City One is the ultimate dystopia. The Dreddverse at its best is a top-class parody that takes the edgy British humor so many of us love and turns it up to 11. Most of it, however, isn’t just played for laughs. Make no mistake, the world of Judge Dredd and the Hall of Justice is as much of a warning as it is absolutely hilarious.

Look around the globe and it doesn’t take long to see how bad society can get when law enforcement decides to act as judge, jury, and executioner. Ditto the way extreme sentencing doesn’t have the effect on reducing crime that many seem to think. For all the punishments and perps Dredd sends to the Iso-Cubes, his work is never truly done.

But it goes oh so much deeper than that.

The Judge Cal saga (my favorite) shows how history can repeat itself no matter how technologically advanced we think we’ve become. Another classic, The Apocalypse War, bravely goes where so many other stories would not dare do: show the aftermath of mutually assured destruction. Stories that take place in the wastes often underline the plight of those left behind. Even nowadays, with series like 2021’s Dreadnoughts (by Michael Carroll and John Higgins), readers are given new ways to learn from Mega City-One’s finest.

The Dreddverse does this by being utterly fearless and never straying too far from its roots as parody. It’s a combination that catapulted Monty Python and others to stardom and keeps Judge Dredd relevant, an icon for all times.

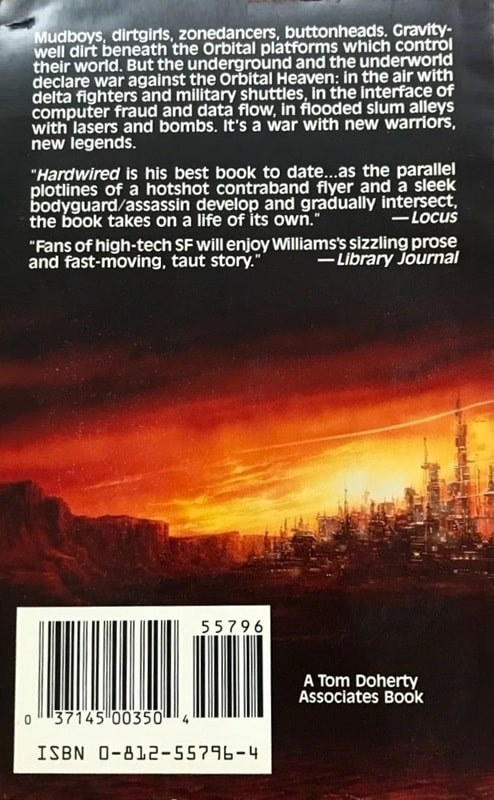

The Work of Cixin Liu

Liu is an author that in recent years has really grown into a massive name. The writer from Beijing has certainly earned the accolades and following. For this entry, I’m specifically focusing on his novel The Three-Body Problem and the short story “Moonlight.” Why is easy to answer.

Both show apocalyptic visions of humanity that are couched in real-world problems we face today. Yes, both offer different takes on how those problems might be solved only to crush readers’ optimism with nihilistic endings so real his work might as well be classified as horror.

What I love about Liu’s depiction of the future in these stories is how they are fueled by mistakes (violence, power-hungriness, climate change) we are trying to reverse now. That’s what makes them so compelling and outright terrifying. For our sake I hope we learn a thing or two from Liu’s writing before its too late.

|

|

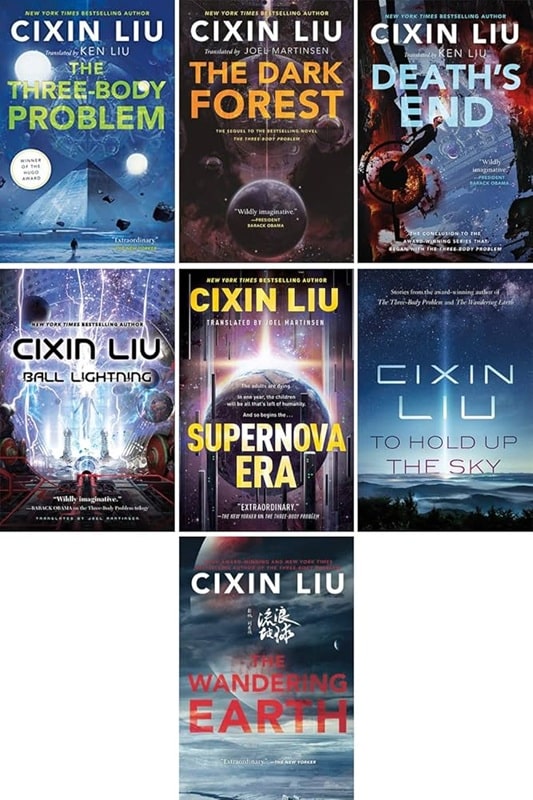

A Canticle for Leibowitz (Bantam, August 1976). Cover by Lou Feck

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

No list of sci-fi dystopias would be complete without Walter M. Miller Jr’s masterpiece. It’s the kind of seminal book that has inspired people for decades. You see traces of it in Fallout, The Stand, The Book of Eli, and so many others. Only Stephen King comes close to matching its narrative power. Even then, The Stand repeats a point Miller made in 1961.

Don’t get me wrong: both books are amazing and well-worth reading. But it’s Miller’s work, in my opinion, that drives home mankind’s penchant for making the same mistakes over and over. It accomplishes this by spreading out the story across generations and giving the communities he writes about time to develop. Other societal factors and how they might be used to the detriment of society also take center stage. Then there’s the explosive (pun intended) end and how it impacts Earth.

But there’s hope here too. Its captured in the adaption of human culture and religion, the good deeds that continue to be done, and the push by some characters to do what’s right no matter the cost. In a sense, Miller is saying that they are as much a part of human nature as the mistakes we make.

By comparison, The Stand has a certain Senor Flagg to blame for the world’s problems. In Canticle, that finger, its problem and solution, are pointed squarely at mankind.

|

|

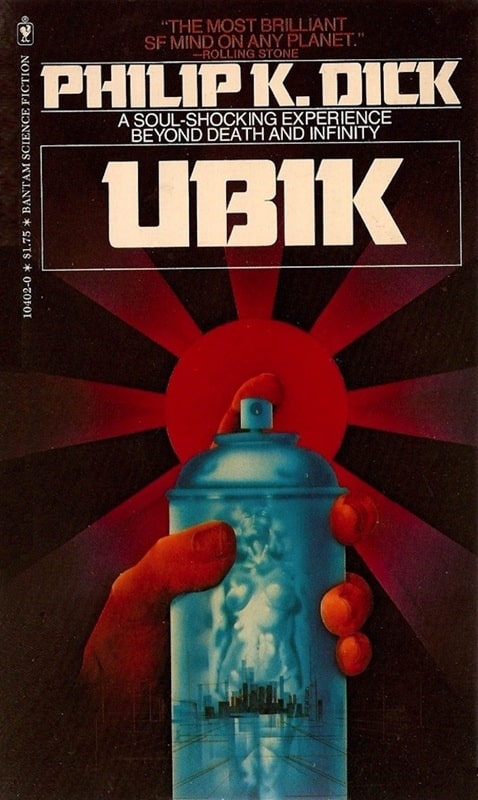

Ubik (Bantam, January 1977). Cover by Gene Szafran

Ubik by Philip K. Dick

Philip K. Dick was a visionary. Decades after his death in 1982 we are still reinterpreting and analyzing his work. Dick seemed to have a crystal ball that looked into the future and used it to write compelling stories that intrigue us till today. He grappled with fascism in The Man in the High Castle and the true meaning of humanity in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? With Ubik, the author sculpts a corporatist world in forensic detail.

It feels and reads so real the book is at times terrifying. He depicts a future so heavily monetized that refrigerators behave like vending machines and psychic powers are used for commercial purposes. The wealthy are able to travel across the world in an instant and, through cryogenics, stave off death, effectively monetizing the last few hours of a persons life.

Its as absurd as it is terrifying and I can easily see a future where life imitates art.

|

|

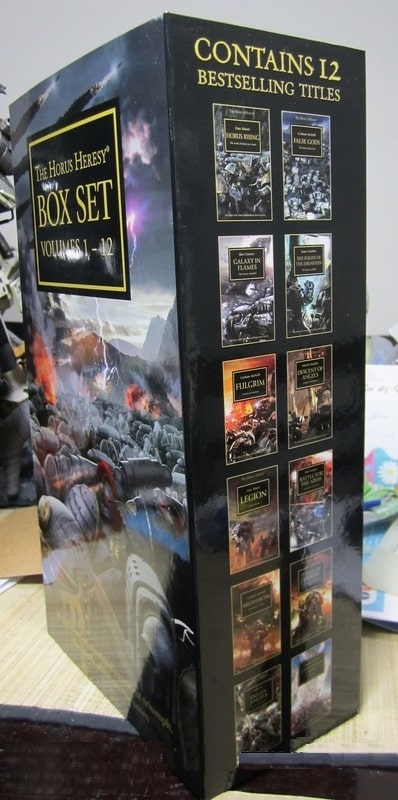

The Horus Heresy Box Set, Volumes 1-12 (Black Library, October 14, 2014)

The Horus Heresy by Games Workshop

Big characters, massive battles, and the death of a golden age are what come to mind when most people think about The Horus Heresy book series. Clocking in at 54 novels and boasting talent like Dan Abnett, its no exaggeration to call it a very special space opera. Underlying everything, however, is the tragedy of humanity’s resurgence and inevitable fall.

Even before the eponymous civil war in the series begins, there are cracks in the imperial project readers will see fall apart. In The Last Church we see just how far the Emperor will go to enforce his believes, the tyranny and oppression he thinks is necessary for mankind. Horus Rising offers glimpses of the man at the heart of it all and the first hints at just what might inspire him to tear the galaxy apart.

Part of why the series works is that it is a prequel to the main Warhammer 40,000 setting. Instead of being a weakness, the authors of the Black Library use it as a strength. Because we know where things end up it makes glimpses of where things could have been so much more tragic. The seeds of a rotting human empire, consumed by ignorance, fanaticism, and seemingly doomed fight for survival are planted here. And boy is it a cautionary tale for the ages.

If there is a single lesson to learn from the series it very well might be this: nothing good comes from oppression. Oh and treat your family well. Not to spoil anything, but so much would not have happened had the Emperor of Mankind simply been a semi-decent father.

The struggles of our characters might take place far from Earth (for the most part) but the series follows the path of every great dystopian story.

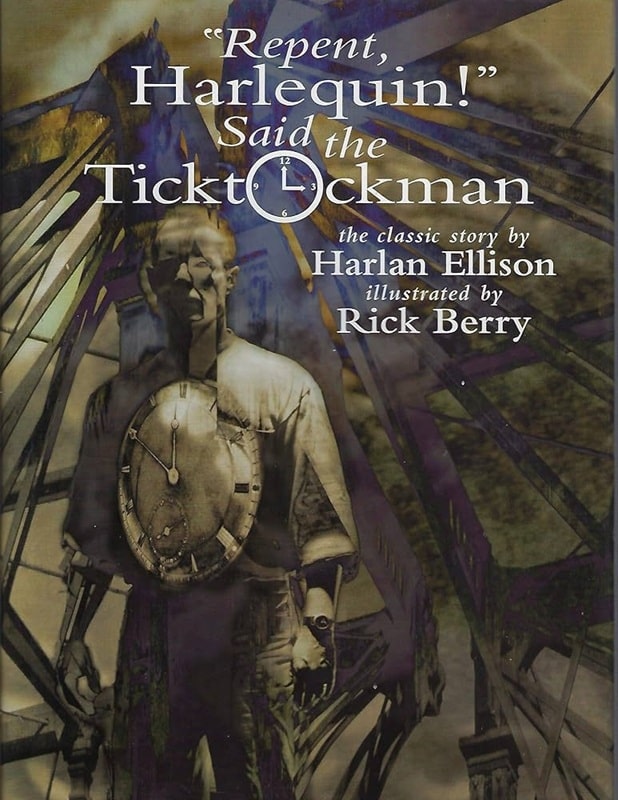

“‘Repent, Harlequin,’ Said the Ticktockman” by Harlan Ellison

Like Philip K. Dick in Ubik, Harlan Ellison explores a highly industrialized nightmare in this story. But in this nightmarish society, humans have effectively been mechanized, reduced to emotionless worker bees that are cogs in a machine. Slaves to endless, sometimes meaningless work.

Most the characters in this story are devoid of the big personalities Philip K Dick worked with in the entry above. Ellison, however, makes up for that with some of the most bombastic and expressive language I’ve read anywhere.

His story is one of rebellion, of using what truly makes humanity special to break down a system that threatens to turn us into something we’re not.

|

|

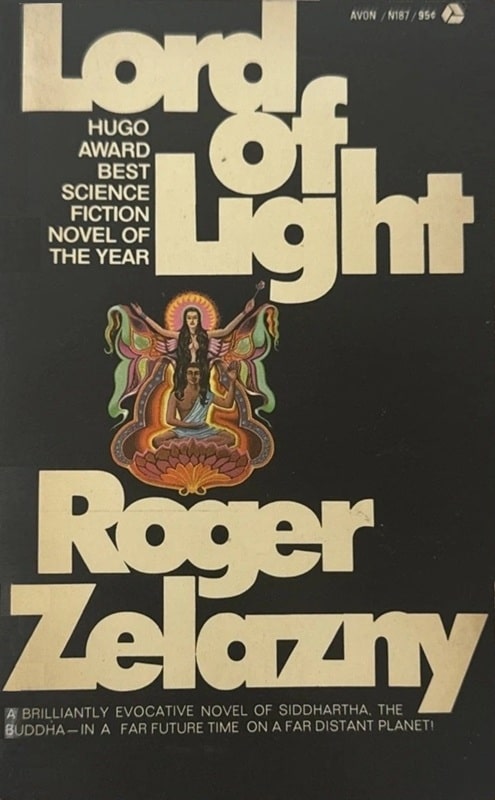

Lord of Light (Avon Books, January 1969). Cover by Ronald Walotsky

Lord of Light by Roger Zelazny

Another story of rebellion against seemingly impossible odds. What happens when technology allows the powers that be to take oppression even beyond the realm of death? Roger Zelazny’s novel answers that question. In the far future, a group monopolizes unimaginably powerful technology to build a totalitarian parody of Hindu-Buddhist myth. Mastering the secrets of immortality, they have positioned themselves as gods, their personal domains cordoned off like a sci-fi Mount Kailash.

They control the masses by weaponizing faith and reincarnation. Even dying offers no freedom, for they have the technology to control if or where a soul migrated to. Blow for blow, it is among the most oppressive societies depicted in SFF. Which makes it an absolute joy to watch the entire thing fall apart.

Any other dystopia’s you think we can collectively learn from? What do you think about my choices above? Let me know in the comments!

Ismail D. Soldan’s last article for Black Gate was Why SFF Mentorships Matter. He is an author, journalist, and poet. His work has previously appeared in Illustrated Worlds, LatineLit, and The Acentos Review among other publications. A proud explorer of both real and imagined worlds, some of his latest published work include The Right Kind of Royalty (on swordsandsorcerymagazine.com) and Heavenfall (in JR Handley Presents: Contested Landing Volume 2).

I really like your addition of Lord of Light to this list.

I would also like to suggest Dr. Adder and The Glass Hammer by KW Jeter, and the Takeshi Kovacs series by Richard Morgan is excellent and under-appreciated dystopian settings.

For a fantasy dystopian setting that I think is criminally under-rated, I suggest the Age of Darkness series by Hugh Cook.