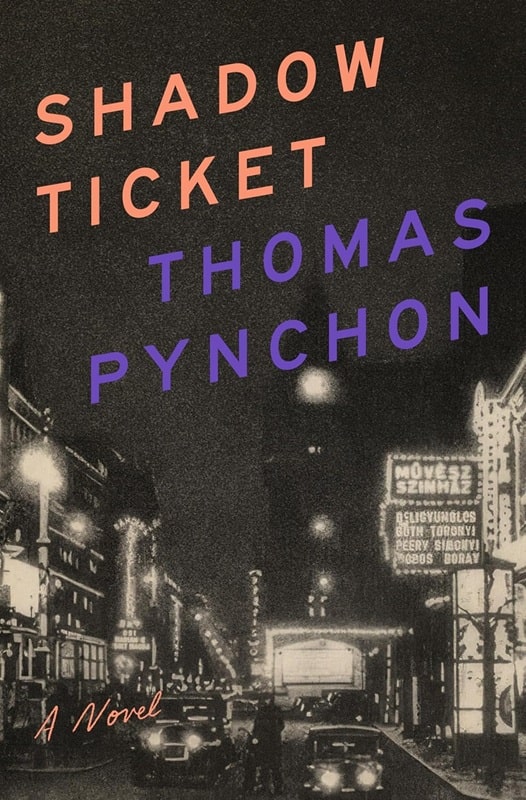

Alt History on Acid: Shadow Ticket by Thomas Pynchon

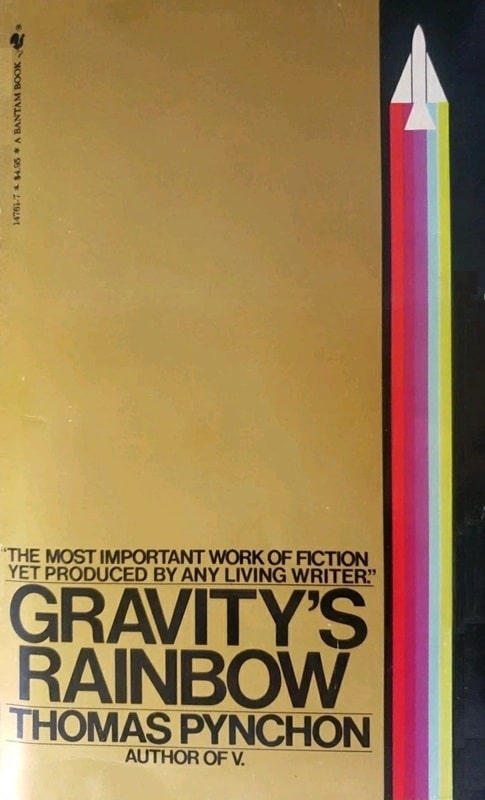

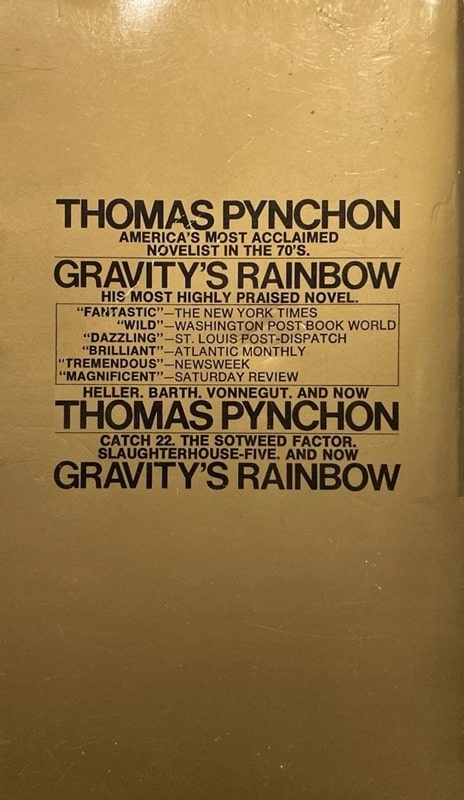

I never really fully understood what Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity Rainbow was about. Much like everyone else. As one critic put it,

I doubt that anyone could account for everything going on in Gravity’s Rainbow, even Pynchon himself, although I suppose he has an edge on the rest of us.

I sort of knew it had something to do with V-2 rocketry and associated penis imagery, fascism and political satire, conspiracies and paranoia, alt-history, combined in a hodgepodge of puns, jokes, silly song lyrics, and linguistic puzzles spread amongst loosely connected absurdist plot lines. And that is sometimes characterized as the

Great American Novel, like Moby-Dick. Unlike Melville’s readers, though, Pynchon’s readers can go for pages at a time without one clue as to what is going on with the plot, setting, or characters.

Which I think is the point. To not know what is going on. Because that’s the way life is; no controlling narrative, but rather a series of random occurrences that nonetheless shape the impenetrable human condition.

|

|

Gravity’s Rainbow (Bantam Books, January 1, 1979)

Which brings me to Pynchon’s latest, Shadow Ticket, a kind of Gravity Rainbow-lite. That’s not a knock, only that at a little less than 300 pages, Shadow Ticket still contains many of the same opaque themes and narrative dissociation that continue to obsess Pynchon (and his fans), but at a smaller (and perhaps more digestible) scale than the 760 page opus.

In keeping with the previous pulp inspired novels Inherent Vice and Bleeding Edge, as well as two word titles (though not meant as any kind of connected trilogy, I don’t think), Shadow Ticket starts out as private detective noir set during 1930s Milwaukee, famous for its beer, cheese (a frequent Pynchon fixation), labor movement, large German-American population and pre-war domestic organizations promoting Nazi ideology.

All of which are elements for Pynchon to build his usual satirical takes on nationalism, ethnicities (warning: not PC at all), American culture, druggie lifestyle, and the general lunacy of existence. But in starting out, at least for the first few pages, Pynchon dons his Raymond Chandler impression.

When trouble comes to town, it usually takes the North Side Line. What with tough times down the Lakke in Chicago, changes in the wind, Prohibition repeal just around the corner, Big Al in the federal pokey in Atlanta. Outfit affairs grown jumpy and unpredicable, anybody needing an excuse to get out of town in a hurry comes breezing up here to Milwaukee, where it seldom gets more serious than somebody stole somebody’s fish. Hicks McTaggart has been been ankling around the Third Ward all day keeping an eye on a couple of tourists in Borsalino’s and black camel hair overcoats up for the home office at 22nd and Wabash down the Lake, the Chicago Outfit handling whatever needs to be taken care of in Milwaukee since Vito Guardalabene cashed in his chips ten years ago, though Vito’s successor Pete Guardalbene is still considered head man in the Ward, gets his picture in the social pages smiling at weddings and so forth.

Hicks appears to be the central character. I say “seems” because he is later sidelined in favor of a number of equally distinctively comically named characters that come and go. But he is the transitional fulcrum for events about to unfold.

Formerly a strikebreaker for hire who, relieved he hasn’t murdered anyone thanks to a strange time warp intervention (the first hint that things are going to start getting weird, along with a WWI-era U-13 German submarine trawling beneath the icy surface of Lake Michigan, not to mention a Nazi bowling team), switches to the private eye trade as an employee of Unamalgamated Ops (because Pynchon organizations never have simple generic bureaucratic names) primarily to document evidence of unfaithful spousal activities. Hicks himself is briefly involved with April Randazzo, a lounge singer who ordinarily prefers married men.

Because he once saved her from the psychiatric experiments of Dr. Swampscott Vobe (besides a funny name, Swampscott, Massachusetts is where a 1960s conference founded “community psychology,” mental health practices to solve social problems), Hicks gets the “ticket” (i.e., investigative assignment) to find Daphne, the missing heiress daughter of Bruno Airmont, the “Al Capone of Cheese.” However, after surviving a hit ordered by April’s jealous Mafiosa lover, Hicks is dispatched, over his objections, to Nazi emergent Europe.

Still in search of Daphne, herself chasing down lover-on-the run Hop Wingdale, clarinetist for the touring The Klezmopolitans, Hicks gets entangled with cocaine-addicted spymaster Egon Praedinger (a possible take on “Otto Preminger”?). Praedinger recruits Hicks to add Ace Lomax, Bruno’s right hand thug, as a “shadow ticket”:

Meanwhile, as you pursue the elusive Miss Airmont, we keep the shadow on you day an night, hoping that Bruno at a moment of diminished attention will make some fateful the lunge and be drawn out of his safe perimeter, even for a fraction of attention, whereupon we are prepared to step in and apprehend.

Here Hicks consults his Manual, a set of detective instructions, likely intended as a satirical poke at formulaic private eye yarns, to ask, “who are you reporting to, who is it that is sending me off into one more miserable damn hopeless ticket that I never heard of, here?”

Pradesinger’s response is that at the “we” isn’t a person so much as the “shadow” beginning to cover Europe:

This is the ball bearing on which everything since 1919 has gone pivoting, this year is when it all begins to fall apart. Europe trembles, not only with fear but with desire. Desire for what has almost arrived, deepening over us, a long erotic buildup before the shuddering instant of clarity, a violent collapse of civil order which will spread from a radiant point in or near Vienna, rapidly and without limit in every direction, and so across the continents trackless forests and unvisited lakes, plaintext suburbs and cryptic native quarters, battlefields historic and potential, prairie drift over he horizon with enough edible prey to solve the Meat Question forever.

Awaiting Hicks on this shadow ticket is a cast of an anti-Semitic Vladboys biker gang, a fascist terrorist training camp, a Czech golem, motorcycle courier Terike and the Trans-Trianon 2000 route running “inside this shadow zone between the concentric Hungaries old an new,” as well as brief guest appearances by various eccentrics. Not to mention the apparition and disappearance of lamps (because they shed light against the shadows, but only if you have one?).

It’s not revealing anything, because who knows exactly what any of this means, that Hicks eventually opts to stay in Hungary with his latest love interest Terike. Things aren’t going particularly well back in the States, where violent dairy strikes imperil Daphne’s cheese inheritance, and FDR is ousted by a military coup. As this conversation taking place on the U-13 sub (remember, I mentioned there was a submarine) approaching the New York harbor reveals:

“There is no Statue of Liberty…no such thing.”

“You said you’re taking me back to the States”

“We are, then again, we’re not.”

“Meaning what?

“It’s the U.S., but not exactly the one you left. There’s exile and there’s exile.”

I suppose that one interpretation of all this is a kind of warning about despotic tendencies in our own current government. Except that this has been a Pynchon theme since Gravity’s Rainbow. Maybe it’s a reminder that autocracy always lurks. But perhaps the biggest clue as to what Pynchon might be going on about is the novel’s epigraph, a line from, who better, Bela Legosi from the 1934 movie, The Black Cat:

Supernatural, perhaps. Baloney… perhaps not.

David Soyka is one of the founding bloggers at Black Gate. He’s written over 200 articles for us since 2008. See them all here.

[…] My latest post on Black Gate is a review of Thomas Pynchon’s latest, Shadow Ticket […]