By the King’s Command: Joan Samson’s The Auctioneer

Every October, I perform a ritual that I suspect many of you also observe — I grab a handful of books off the shelf and spend the Halloween month reading the scary stuff, always trying to get in a “classic” or two that I’ve missed along the way. Last year that classic was Christine, one of the “first-wave” Stephen King books that I had never gotten around to, and the novel reminded me why the man is so enduringly popular… and also why I don’t read him much anymore. I enjoyed Christine, but five hundred plus pages of dated pop culture references and slangy, apocalyptic adolescent angst is a heavy load for someone of my advanced age to carry.

I didn’t read any King this October, but my Halloween 2025 reading had a King connection nevertheless. In his chatty 1981 grab-bag horror survey Danse Macabre, King includes a list of approximately one hundred horror books that he considers important for the post-World War Two era he discusses. (He was born in 1947.) I incorporated many of King’s choices in my own megalomaniacal list of essential horror, fantasy, and science fiction books, and over the years I’ve sampled a fair number of his recommendations. I’ve found the Master’s lineup hit or miss; there have been whiffs like Iris Murdoch’s The Unicorn (which I absolutely hated, and which I’m convinced he inserted strictly for literary cachet), home runs like Ramsey Campbell’s nightmarish The Doll Who Ate His Mother, and books that may not be masterpieces but are still solid successes, like another one I read last year, Bernard Taylor’s grim English ghost story, Sweetheart, Sweetheart.

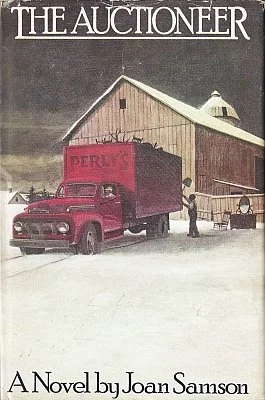

This year the first October book I read came off of King’s list — The Auctioneer, Joan Samson’s 1975 novel of rural unease. King marked some of the books on his list with an asterisk as being “especially important”, and The Auctioneer is one of those.

Harlowe, New Hampshire, is a sleepy rural community where people know and get along with each other, and John Moore and his wife Miriam are content to work the farm that has been in John’s family for generations, while raising their daughter Hildie and caring for John’s elderly mother. Everything is settled and secure… until the arrival of a stranger from “outside”, Perly Dunsmore, the auctioneer.

The glib and hypnotically persuasive Dunsmore initiates a series of auctions, all to raise funds for the “improvement” of the adopted town that he professes to love and desires to protect (or so he says). The auctioned items are solicited from the basements, attics, and barns (and eventually living rooms, bedrooms, and kitchens) of the locals, and the proceeds go to enlarge the police force and upgrade fire and medical services. Who could possibly object to that? Initially, no one… until the police force has far more officers than such a small town needs, and those officers have grown increasingly arrogant and overbearing, intimidating the citizens, at first in subtle ways, and then in more overt ones.

Soon people’s weekly contributions to the auctions seem far more coerced than voluntary, and those who have been heard to grumble start to meet with “accidents.” It’s not long before people (including the Moores) are rattling around in houses that are almost empty shells, stripped of anything of value, and when the darkly charismatic Dunsmore begins driving people off their property and starts auctioning off boys and girls from families so impoverished by their compulsory “donations” that they can no longer support their children, things rapidly come to a crisis.

At first, John tries to let outside authorities know what’s going on in Harlowe (he even tries but fails to talk to the Governor of New Hampshire) but always meets with either condescension, indifference, or outright praise of the enterprising and forward-thinking auctioneer, who seems to have everyone in the state, high and low, safely in his pocket. And after all, what real proof of wrongdoing or illegality does Moore have? (Dunsmore has obtained legal sanction to facilitate and expedite the adoptions, all in order to provide quick relief for all these poor, distressed families and their needy boys and girls.)

Driven to desperation, John eventually tries to start a fire that will burn down the houses of the worst of Dunsmore’s deputies (some of whom serve him out of greed and the lust for power, while others — perhaps the majority — are simply terrified of him). The attempt at insurrectionary arson inexplicably fizzles (no houses are burned down or even damaged, though by all rights several should have been), but the situation comes to a head when Dunsmore and his stooges lose control of a traditional New England town meeting, as first one citizen and then another speak against the auctions, at first hesitantly, then with mounting courage and anger. The outraged people of Harlowe, finally having found their voices, finally chase Dunsmore across the village square and into his luxuriously furnished house, which they proceed to break into, vandalize, and burn to the ground. (The house turns out to be filled with the finest items that months before had adorned the homes of Harlowe’s original citizens — of course.)

The retributive riot is led by John Moore, who has come to suspect that his farm and his daughter are going to be the next items to fall under the auctioneer’s gavel. The town is saved though perhaps irreparably damaged, and Perly Dunsmore escapes (though there is no way for him to have gotten out of the house), seemingly vanishing into thin air, in the same mysterious way he appeared at the beginning of the book. After this violent catharsis, the book concludes as a peaceful snow falls on Harlowe, with the snowflakes “sticking to trees and roofs, catching on the new skim of ice over the pond, and blanketing the frozen earth. Somewhere, perhaps, they fell on the auctioneer.”

The Auctioneer was Joan Samson’s first novel, and she was at work on another when she died from brain cancer shortly after the publication of her only book, which can’t escape some of the common defects of many first novels. The pacing is uneven; the whole story has a stop-start-stop-start rhythm that makes it feel longer than its 239 pages, and not in a good way, and the overall focus wavers, making it sometimes seem that Samson was unsure just what kind of story she was telling. Is The Auctioneer an allegory of the way modernity and “progress” lay waste to traditional communities, or is it a just a horror story? Is the book deliberately vague or does the uncertainty stem from the struggles of a neophyte novelist to control her material?

This question is especially pertinent when we consider the character of Perly Dunsmore himself. Who is he? What is he? What does he want? What is the nature of the hold that he has over Harlowe and its people? Is he a person or a devil or a symbol or all three? Though there is no overt supernaturalism in the story, there is plenty of ambiguity, and when I finished the book, I still wasn’t quite sure how to answer many of the questions the novel raises. But Dunsmore’s enigmatic nature is a strength as well as a weakness; part of the reason John and his friends seem so helpless is because they’re never quite sure what they’re dealing with; coming to grips with the auctioneer is like trying to corner a patch of fog. Dunsmore’s very slipperiness makes you want to get a firm hold on this cryptic figure, and that desire keeps you turning the pages. The book is puzzling and even sometimes frustrating, but it does hold you to the end, and it lingers in the mind afterward.

Even admitting its significant faults, Samson’s story is deeply felt; her small, vulnerable New England town is the kind of place that she clearly knew well and cared about deeply; she convinces us that the menace that faces her decent but unsophisticated people is very real, and because of that, she is able to convey the fear and anxiety and helplessness that her characters feel to her readers (or to this one, at least).

Ultimately, though, The Auctioneer is a book in which the strengths and weaknesses are in almost perfect balance, and while there are too many good things in it for me to write it off as a failure, neither can I call it a complete success, which poses the question of why King considered such a mixed book to be so significant, elevating it over better-known, more highly regarded works on his list like Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, Robert Aickman’s Cold Hand in Mine, or Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books, none of which rate the “particularly important” asterisk.

Looking closely at the Danse Macabre list, it becomes apparent that the books that meant the most to King are the ones that he found the most fruitful when it came to his own work, books like Robert Marasco’s Burnt Offerings (one of the nastiest haunted house stories in all of horror fiction) a book which — as King has always readily acknowledged — provided one of the main sparks that would later be kindled into The Shining. (Honestly, I think Marasco’s novel is even better than King’s.) The domestic, daylight horror of favorites like Richard Matheson’s I am Legend and Anne Rivers Siddons’ The House Next Door provided a template for King and gave him permission to center his tales in a contemporary, housing-tract, strip-mall America peopled by ordinary, working-class people occupied with their everyday lives and commonplace concerns.

I think that Joan Samson’s single flawed but fascinating novel is one of those books that began a chain reaction in the brain of the most popular and successful of modern horror writers. It’s tragic that she didn’t live to complete another book (she was only thirty-eight when she died), but I’d be willing to bet that the sole child of her cut-off-too-soon imagination, The Auctioneer, has at least one healthy descendant — a novel that Stephen King wrote in 1991 about a small town debased, degraded, corrupted and nearly destroyed by a sinister, enigmatic stranger who disappears at the end, perhaps to begin his evil work in some other unsuspecting community. Sound familiar?

If The Auctioneer was a seed that eventually grew into Needful Things, then it’s a book well worth reading, both for its own intriguing qualities (and as a memorial to someone we lost too soon), but also for the dark fruit that grew from its pages so many years later.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Bloody Good Time for Young and Old: Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales

I started reading this two November’s ago after the book had a bit of a resurgence and was republished as part of the Paperbacks From Hell series. I put it down after a few chapters for many of the weaknesses you cite but always meant to get back to it.

One of the contextual strengths of the book was how it may have reflected rural anxiety to the massive white flight / suburban expansion of its time (my family had moved from the city to the country in ’74 and the locals never accepted us) along with the seventies fad of auction houses and antique stores scouring farm communities for everything they could make a buck on. I remember my family going to a few auctions and farm estate sales where a fair amount of white collar city dwellers were snatching up everything in sight. I also remember the very isolationist township we lived in passing strict restrictions on housing developments in direct reaction to neighboring communities where many huge farms were being carved up into suburbs.

The book does have a nice seventies popular fiction vibe (a weakness of mine) and I do plan on getting back to it.

“Danse Macabre” is an enjoyable enough read but it seems very much like a one-draft book written in a white heat. A lot of its criticisms don’t hold water and I would never recommend it as a reference.

It’s been a long time since I read Danse Macabre. King is of course frighteningly well-read in the horror genre – and frighteningly opinionated – and his views are naturally highly personal. I’m fine with that, but I agree that the book’s limitations have to be acknowledged. It’s certainly the opposite of an objective or cool-headed account of the genre.

Even though as a 1980s teen I read and reread Danse Macabre and checked his list of recommended books, I somehow completely overlooked The Auctioneer till about 2010 or so, when I saw it mentioned in one of the long-gone message boards Amazon used to have. I found a cheap copy at a library sale almost immediately after, and honestly I found it well-nigh unputdownable. I’m almost afraid to revisit it after so many years because I had such an unexpectedly satisfying time reading it! Who knows what works she would have done…

Hi Thomas—sorry to contact you via comments; I couldn’t find another channel.

I’m with Wolfman Ink, and we’re developing a new, reader-friendly edition of Varney the Vampire. We’d love to hear from readers who attempted it and hit the common obstacles. If you’re interested in knowing more about what we’re doing, please email ejbyrne@wolfmanink.com. Thanks!