A Blurb Reader’s Bill of Rights

I don’t know anything about the amount or quality of your reading. You might read quickly or slowly. You might be a sprinter who favors short stories or a marathoner who fearlessly commits to one multivolume series after another. You might read one book at a time or you might be the kind of degenerate who always has half a dozen going. You might read six books a year or sixty.

Whatever the nature of your reading life, though, I’ll bet that over the course of that life, you’ve read enough blurbs to make a volume as hefty as War and Peace (my copy of which does not bear a blurb. What would it even be? “If you liked Norm MacDonald’s Moth Joke, you’ll love this!” — Conan O’Brien”? It would be interesting to figure out just how long an author has to be around before blurbs are no longer considered necessary, but that’s a conundrum for another day.)

For readers, blurbs are a fact of life. They can be helpful, like a considerate stranger who gives you directions in a strange city, and they can be annoying, like mosquitoes or those people who keep calling me, offering to buy my house, and I don’t want to sell my house!

I am admittedly a stranger to the travails of blurb writers, but I certainly know all about the problems of blurb readers, and having nothing better to occupy my mind, I have formulated a little something for those of us here on the receiving end — a Bill of Rights for Blurb Readers. The actual Bill of Rights found in the Constitution (remember that?) lists ten inalienable rights, but I’m no James Madison, and I have only been able to come up with eight of them for my revolutionary document. Shall we begin?

- Blurb readers have the right to blurb diversity. Good luck getting it, though, because publishers (naturally enough, I suppose) mostly solicit blurbs from people who write books that are exactly like the book they’re soliciting the blurbs for. But of course writers of YA feminist steampunk timeslip comedies think that this particular example of a YA feminist steampunk timeslip comedy is the cat’s miaow. Why wouldn’t they? Such a recommendation is fine as far as it goes, but a rave from someone with a radically different sensibility who writes a completely different kind of book would go a lot farther. Or is it further?

- Blurb readers have the right to be free from absurdly exaggerated historical comparisons. If you’re going to compare a writer to Charles Dickens, for example (a much-abused man in this regard), circumspection is definitely called for, and under no circumstances should you tell readers that this writer is “The new Charles Dickens.” There is no new Charles Dickens, and I suspect that this tactic is most employed when the blurber has a Gibraltar-solid confidence that the blurb reader is almost completely unacquainted with the works of the old Charles Dickens. (If you fall into this category, put down that Stephen King and go read some Dickens. I recommend starting with Oliver Twist.)

- Blurb readers have the right to expect that words — even outside the actual book — will be used carefully. The overuse of “masterpiece” and “classic” only tends to devalue those terms, and for that very reason, I doubt whether they even sell many books. After all, according to the OED, a masterpiece is “a production of art or skill surpassing all others by the same hand; also, in wider sense, a consummate example of some department of art or skill”, and a classic is “of the highest class.” In other words, true examples are by definition few and far between and in any case, it’s more pleasant — and persuasive — to be gently massaged than to be belabored like George Foreman’s heavy bag. And this leads directly to —

- Blurb readers have the right not to be bludgeoned with too many blurbs. Less is usually more, and three or four good, sharp appreciations from people worthy of respect tip the balance more than three or four (or, God help us, even more) solid pages of raves from the likes of the Arkadelphia Morning Picayune or the Lompoc Intelligencer. Once a decent, discreet number of blurbs has been exceeded, I start to think that someone is trying to put something over on me, and I half-expect that the last blurb is going to ask me for my PIN number.

- Blurb readers have the right to know that this book, whatever its many excellences, is not going to change their lives. I don’t know how many books I’ve read in my life; whatever the number is, it’s a big one. I’ve read a lot of ephemeral trash, and I’ve read many immortal masterpieces, and I’ve read a lot of books that fall somewhere in-between, and if I had to list the ones that have actually changed my life (one of the careless blurber’s most overused promises), it would be a very short list indeed. (Would anyone even want that? If every book — or even every fourth or fifth or sixth — was a life-changer, that would quickly grow exhausting, and I’ll bet your spouse wouldn’t be crazy about it, either. Hell, in those circumstances I’d probably give up reading altogether.)

- Blurb readers have the right to be skeptical of the dreaded Overblurber. Yes, I’m talking about Neil Gaiman, and not just because of the mess he’s recently found himself in, though admittedly the number of people who covet a five-sentence Gaiman-penned rhapsody for the cover of their book has likely dropped close to absolute zero. In his heyday, though, his name seemed to be on almost every sf/fantasy/horror book published, and if he actually read every book he blurbed, I don’t see how it was possible for him to have had enough time to write anything of his own. Anyway, nature abhors a vacuum, and I’m sure someone is even now ramping up to take Gaiman’s place as Lord High Overblurber — be on the lookout.

- Blurb readers have the right to have their independent intellects recognized and respected. In other words, blurbers, don’t automatically assume that my definition of a good book begins and ends with politics. Don’t think that all you have to do is drop in the right cue words (whichever side of the Great Divide they signify) and I’ll start salivating all over my ATM card. (This is another one that falls into the “good luck” category, though, as we seem to live in an age of increasingly ideological writing and reading, which means that we’ll probably see more of that kind of blurbing, too. And why not? Of all the excesses I’ve listed, it’s probably the only one that does sell books.)

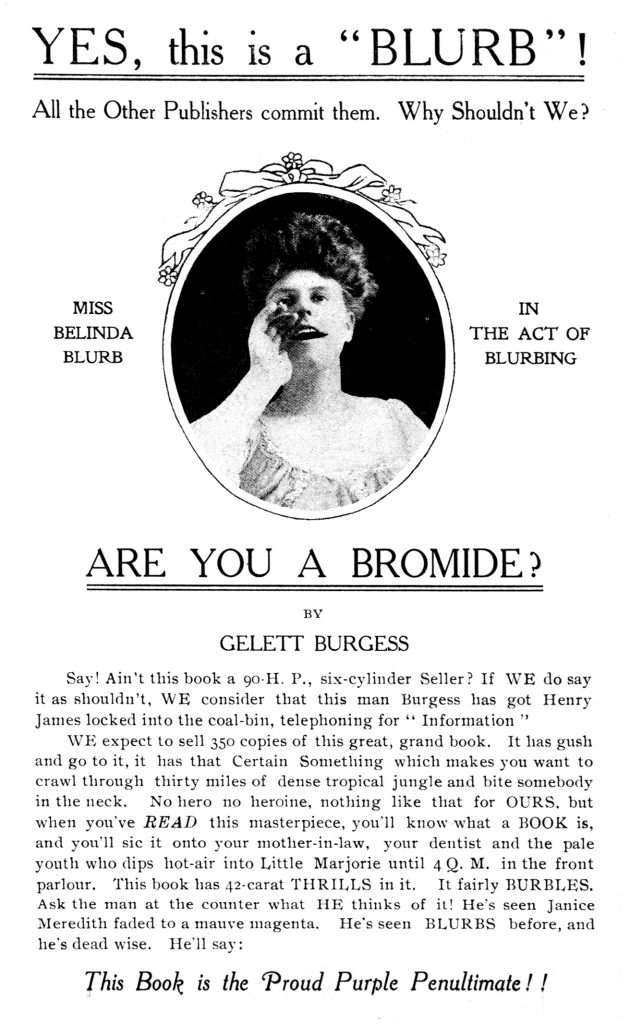

- Blurb readers have the right to read all blurbs, some blurbs, or no blurbs at all, and to agree or disagree, be persuaded or unpersuaded, be delighted or annoyed by them as they see fit. Which is good news, because although verse drama, epic poems, and radio plays have gone the way of all flesh, blurbs are proving to be one of the more resilient literary forms; they’ve been around for at least a century-and-a-quarter (the word itself was coined in 1907 by Gelett Burgess — the “Purple Cow” guy) and they show no sign of going anywhere, so we might as well get used to them… sort of like mosquitoes.

Therefore, as Gelett Burgess could have said (but didn’t), “I never wrote a beauteous blurb, / Although I sometimes read one; / Sitting in my mild suburb, / I’d rather read than need one.”

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was The Last Legionnaire: Jim Shooter, September 27, 1951 — June 30, 2025

0.o “[Y]ou’ll sic it onto […] the pale youth who dips hot-air into Little Marjorie until 4 Q. M. in the front parlour.” …I’ve sicced books onto my dentist, before, but have no idea what sort of work would induce me to press a book upon the referenced potential rapscallion.

Excellent bill of rights! Though, I feel a little bad about having immediately identified the current Lord High Overblurber. Certain author names just sort of turn a blurb beige.

I’ve never been fond of blurbs, except for one function–telling me what I might NOT like. When George R. R. Martin (for example) gives a book his seal of approval, I look twice for a more reliable opinion. Stephen King’s blurbs are, to me, the absence of words–he’s turned getting paid per syllable into a small fortune and probably writes copy in his sleep.

When the coun of the realm hasn’t been cheapened, on the other hand, it will grab my attention. Got a blurb from Octavia Butler? Now I’m paying attention.

Give me a good Introduction over a dozen blurbs any day.

I didn’t even think about using a blurb as a “negative recommendation.” My Constitution already needs amending…

nice list. and dont sweat the amendments – a good constitution is a living document.

re: diversity of blurbs, i once got a blurb from a famous cookbook author for my toy photography zine. hows that for a juxtaposition?

Pulled a book from my TBR shelf and instantly thought of this article. Came across a combination of #2 (comparing to a particular famous author) & #3 (calling it a classic or a masterpiece). Comparing the book to what is probably THE Greatest Work of a particular genre – something that is so overused with fantasy blurbs . “Moves in the same vein as the Tolkien Trilogy”…..Orlando Sentinal. The book? “The Crystal Gryphon” by Andre Norton. We’ll see how well it holds up.

Thanks for the fun and funny article, Thomas.

Curiously, I recall Algis Budrys in Asimov’s describing Stephen King as the “new Charles Dickens”, and I must admit, the more I thought upon it, the more I was convinced it was an apt comparison, perhaps due to Mr. King being busy at the time with his serial publication, The Green Mile, a novel published in monthly installments, a process often used with Dickens’ novels.

And as for favorite blurbs, my own is due to Mr. Michael Moorcock, who is known to toss “Just as good as Tolkien” at publishers. Which is much less appealing when you find out just what Mr. Moorcock thinks of Prof. Tolkien’s works.

Chuck and Steve both wrote long books, some of which were published serially, and both writers were wildly popular (more so with the public than with critics, at least initially).

After that, the path diverges, at least as far as I can see. (KIng has certainly treated his wife better.)