Shouldn’t the Missing Be Missed?

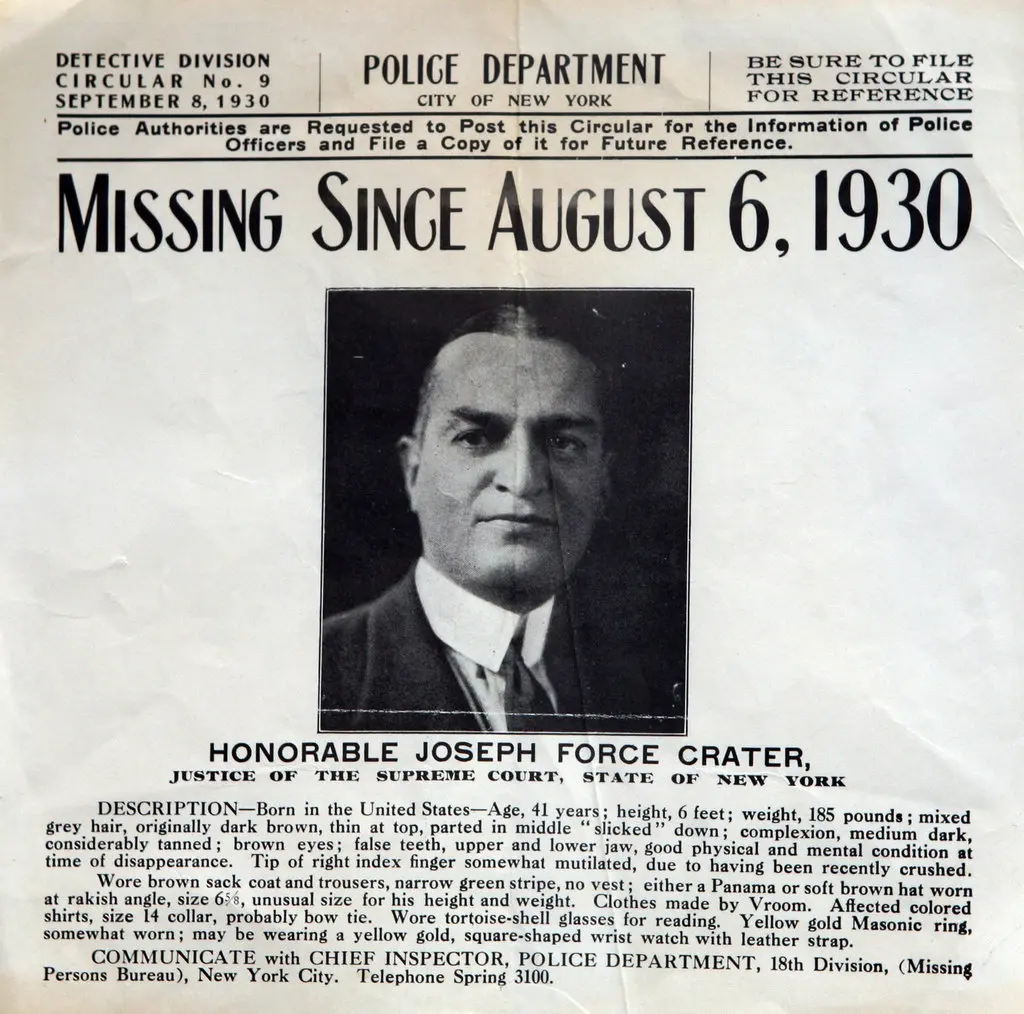

I’m a big fan of mystery stories, and I’ve read a lot of the genre’s major writers, from well-mannered Brits like Doyle, Christie, and Chesterton to hard-hearted Yanks like Hammet, Chandler, and McBain. A lot of their stories begin with a disappearance (even if they end with a corpse), and though in fiction the Great Detective always solves the case, in real life many disappearances remain unsolved, which makes them the most baffling mysteries of all. That may be why people still debate the fate of Judge Crater, search remote islands for a trace of Amelia Earhart, and argue over whether the New York Giants snap the ball over the remains of Jimmy Hoffa.

I don’t spend much time worrying about those folks — what really bothers me are the people who disappear on the internet, without Hercule Poirot or Philip Marlowe ever so much as lifting a finger to find them.

It happens every day, and if you’re part of an online community, you know this to be true.

Now before going any further, I have to admit that there was time when I rolled my eyes at any mention of “online communities.” I didn’t believe that such virtual congregations were really communities. Perhaps that’s because I was in my late thirties when the internet appeared out of nowhere and swept all before it like a horde of hungry Visigoths, which makes me one of those awkward amphibians who were shaped by and lived the first half of their lives under one paradigm, but have had to live the second half under a radically different dispensation.

Or maybe I’m just a natural contrarian, a sour so-and-so. I’ve heard that more than once.

In any case, I eventually adjusted to the new reality, and my views on online communities eventually changed. A lot of things brought that about, the biggest one being Black Gate.

I’ve been a contributor here for twelve years and was a daily reader and commenter for a few years before that. If you spend that much time somewhere, you inevitably get a feel for the place, whether the location is physical or virtual, and you come to know the people there.

Of course, we’re all here because we have certain shared interests — we’re not reading and talking about fly fishing or fantasy football, after all — but those interests and the things we say about them (and the way we say those things) allow us to get to know each other quite well, especially over time, and the result is that there are some folks here at Black Gate that I feel that I know almost as well as I know the people that I work with every day.

Certainly, face-to-face and virtual relationships have significant differences. I’ll never get a phone call at work from any of you like I did from my neighbor Francisco, the day he heard my wife hollering and pounding on the garage door as he was walking by (she had locked herself in there). I’ll never ask any of you to bring a dessert to one of my annual Cruel Yule celebrations, where my friends and I gather to watch terrible Christmas movies. None of you will ever put a new floor and toilet in my back bathroom like my brother-in-law just did for me.

It’s the lack of that sort of in-the-flesh contact that originally made me dismiss the idea of online communities altogether, but over time I came to see that while the differences are very real, that doesn’t automatically disqualify online groups, doesn’t put them beyond the pale of genuine community; each kind of relationship is better in some ways and worse in others, but both can be just as valid. Black Gate is a true community, and it’s one that I am proud to be a part of.

However, there is one major difference in the two kinds of community that I can’t accept so readily, even after three decades of living increasingly online, as most of us probably have, and it’s this: virtual communities have a tendency to suffer unsolved disappearances to a really alarming degree; sometimes the internet is a kind of Bermuda Triangle (if the Bermuda Triangle were a real thing, which it isn’t).

I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently because of a blog that I visit regularly called First Known When Lost. It’s a one-man operation run by a retired attorney named Stephen Pentz (for his profile image he chose a picture of Ulysses S. Grant standing in front of his tent at Vicksburg, which made me like him right away), and the blog is devoted to reflections on the passing seasons in the Pacific Northwest where he lives and to the nature poetry that he loves, mostly by classic English and Japanese poets. (He especially favors Edward Thomas and Bashō.)

I discovered the blog by chance several years ago and I drop by frequently to read and comment, usually sharing a poem or two that I find relevant to Pentz’s theme of the moment. He always responds with gracious appreciation and enthusiasm. First Known When Lost is a place of beauty, tranquility, and wisdom, and my life would be poorer without it.

And I think it might be done.

Stephen Pentz has never been an every-day blogger. His meditations are long and finely wrought; you can tell that he thinks and writes, not hastily, but carefully. Though his pieces appeared more frequently in First Known When Lost’s early years (he started the blog in 2010), for the past half-decade he’s averaged a post a month, and a slower pace is only natural for an older writer whose theme is the long, slow changes of life. Then last year, in 2024, six, eight, or even ten weeks would sometimes pass between posts; clearly, things were beginning to wind down.

In a few days, it will be five months since Stephen Pentz’s last post; it was still winter when he wrote about the cold December moon, which prompted me to send a comment that included my favorite moon poem (“Aware”) by D.H. Lawrence. Since then, winter has ended, spring has come and gone (an entire season with all of its subtle changes) and now we are almost a week into summer, and my comment still has not appeared, nor have any later ones and there have been no new postings or any other activity on the blog since Pentz’s reply to a comment on February 3rd.

For the moment, at least, Stephen Pentz has disappeared. I have poked around online to see if I could find out anything, but people who blog about old poetry don’t enter or exit places noisily, and I’ve come up empty. I very much hope he’ll be back any day now with some observations and poems about the summer of 2025, but I’m beginning to think that’s not going to happen.

If Stephen Pentz were a friend who lived down the street from me and he just disappeared, I’d very quickly know about it and I’d know who to talk to — his relatives, neighbors, the hospital, the police — but because ours was “merely” an online relationship, I’ll likely never know just why he vanished. That bothers me.

To bring it closer to home (this home, anyway), for several years we had a faithful reader around here named Smitty. From his frequent comments, we knew that Smitty was a retired English professor and a widower who lived in Ohio and loved the “good old stuff.” His lively comments on my pieces and on those of other Black Gate writers were unfailingly appreciative, insightful, and good humored. Smitty was a valued member of our community, and not many days passed without us hearing from him.

It was probably a couple of years ago that I realized that it had been quite a while since I had seen Smitty comment on anything, and now it’s been almost three years since his last comment. For eight years he was a friend and a neighbor, even if only an online one. Then one day, he wasn’t, and because of the peculiar, disembodied nature of the internet, it took too long for me to even notice that he wasn’t around anymore.

Smitty and Stephen Pentz can stand for many others, writers and commenters, who have come and gone, here at Black Gate and at many other places in the Brave New World. Most are probably just fine; the shifting currents of life have simply carried them somewhere else, to new interests and different communities, and some even reappear long after you’d given up ever hearing from them again. But many are gone for good, usually without your ever knowing why. It’s an aspect of online life that we have to accept, I suppose, but I wish it weren’t so. I wish I knew what happened to Smitty.

All we can do, I guess, in this world of screens where people can go missing without even being missed, is to make an extra effort to try to notice and appreciate them while they’re still around, so that they’re not, in the wistful words of the Edward Thomas poem that Stephen Pentz named his blog after, first known when lost.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Movie of the Week Madness: The Horror at 37,000 Feet

I recently discovered your blog and I am appreciative of what you are creating. As a former English teacher and current library director, we share many of the same interests…which, for me, is a rarity.

It’s so common for people to come and go in our lives. If we are mindful creatures there are moments when we notice those losses. I imagine sending out a tiny radar pulse to the person, hoping to “ping” them and bring some small subconscious itch that I am thinking of them. If they are sadly departed from the earth I hope the ping finds their energy somewhere out in the universe.

Sending out a ping to Smitty and Mr. Pentz now. Even if they are gone, they are not forgotten.

Thank you for your kind words – we’ll take all the appreciation we can get!

In a way, you’re discussing a more intimate version of the pre-Internet/pre-social-media times when an author not large enough to garner national attention went dark. After a few years with no books, the initial question was, “What happened to the characters/world I knew so well?” Then, after that, the more enduring question became, “What happened to the author? I hope {|s}he’s alright.” I’m slowly tracking down the ones who vanished; it was a blow to finally find out about John Steakley, earlier this year.

The Internet is now about 40 years old, 30 of those years under mass-usage, and that’s long enough to see some trends in how Internet communities develop over their lifetimes. If I may offer some observations?

“The Mass Community”– Tends to gather people by dint of ease-of-use, peer pressure, and sheer variety of sub-communities contained. Partially acts like a black hole, in that everyone gets sucked in and anonymized, partially acts like a coin-sorter, in that individual community members get drawn into and known within sub-communities based on common interests. Long-lived, but of inconstant character. There is frequent and sometimes rapid turnover of community members, including frequent returns of absent members, but only those previously of the community at the same time will recognize returnees. These tend to be “if you leave, you can’t ever come home” communities. Examples: Reddit; 4chan; Discord; The Democratic Underground; X/Twitter and its cousins.

“The Niche Community”– Tends to be a small gathering of people bound by a common interest, sometimes with feelings about either rejecting the outside world or having been ridiculed by the outside world. Can be very short-lived, but can also last for decades, being dependent on the time, energy, and desire to interact possessed by core members. Departures are infrequent after an initial settling period, but any that do occur tend to be permanent. The death knell for these communities rings if their gateway website goes down or the most communicative member departs, either event leaving the community an island instead of a peninsula, and likely to gradually peter out. Examples: TSIDF; F-F-C Forums; most of the communities attached to the Noughties webcomic bloom.

“The Magic Community”– Tending toward a middling size between the mass and niche communities, common interests and sub-communities may form in this sort of community. Arrival and departure rates tend toward roughly equal. Very long-lived. The magic community’s success rests in two factors: accessibility and general decency. Enough new community members can easily find and enter the community, and it remains easy enough for older members to stay and continue interacting. The politeness, gentleness, and lack of attempts to exercise social power over each other encourages community members to stay long-term, and sticks in the mind of the departures as a safe haven. After long absences, departures return and find the magic community to still be the same home. Example: Godville-the-Game.

Black Gate has some of the qualities of a niche community, but it has the decency aspect of a magic community. Perhaps Smitty will one day return, and you’ll be here to welcome h{im|er} home.

Until then, at least there are two phone numbers available and no obituary for your solicitor-poet friend, Mr. Pentz, if you get truly concerned for him. I’m sorry to hear that he is no longer posting.

I’m glad you mentioned decency; it’s what’s kept me hanging around here for so many years, beyond “Oh, here’s some people who like Edgar Rice Burroughs!” Something I quickly noticed about BG is that people tend to treat each other with courtesy, even in disagreement. I saw why early on, when someone took exception with a comment I made on something – no big deal, I’m sure I’m wrong as often as I’m right – but did so in a nastily personal way. (Of course we didn’t know each other from Adam.) The next comment was by the Lord High Executioner (name of O’Neill,) letting that person know in no uncertain terms that that sort of thing would not be tolerated at Black Gate. That kind of line immediately being drawn is not something you see that often – certainly not often enough.

What a blessing to have the boundary of general decency defined and enforced. 😀 The only two other magic communities I’ve been a part of were both self-policed, so things got a touch squidgy from time to time.

Decency really does make a difference.

I’m a solitary person who shuns groups and crowds. I can enjoy the company of a thoughtful person for awhile but three is always a crowd and I’ve never had any desire to be a part of any community. The closest I’ve ever come to uding social media has been the comments section of a handful of websites like this one and a few blogs written by people whose oddball interests overlapped somewhat with mine. I’ll occasionally leave a comment if I think a piece was insightful, well-written or just fun because I feel good work should be acknowledged.

Your story struck a nerve even though I don’t usually indulge in nostalgia for the internet. It reminded me of those ghost town blogs I’ve stumbled across over the years. The ones whose creators labored over for a decade or even longer then gave up because of other commitments but left up and running as something of a haunted archive of a passion they once sank a large amount of time and effort into. Most of them had a final commentary, thanking their readers for the time and interest they invested in visiting the site and wishing all a fond farewell. A few of these sites though were abandoned Roanoke-like without any final message. Like the experience you described, the posts became few and further between until one day…just silence.

One site in particular really got to me. I discovered it only just last winter after I had to visit a mall several towns over in search of a piece of seasonal clothing I was looking for but couldn’t find in my own area. I’ve never had any love for malls. I find them cold and antiseptic and always resented how they killed so many downtowns. This one, like so many others these days, was in its death throes. Three-quarters of the storefronts were vacant including a Sears and the enormous skeleton of a former Hudson’s, a once grand and beloved Detroit area family department store.

Many of the empty spots still had partially removed Christmas decorations hanging in their windows and some of the closed food vendors still had food left on display. The owners or the last employees just walked away. But the mall had been built in the heady retail days of the sixties and still had much of its cool, at the time very modern mid-century architectural elements intact and the sight brought back a flood of early childhood memories of my iwn hometown mall which, coupled with the current almost post-apocalyptic state of the place, left me feeling more emotional than I would have imagined.

I was so affected by the experience that when I got home I went down the rabbit hole researching the history of the mall. I discovered a number of websites devoted to mall nostalgia and one in particular caught my eye. It was crude but genuinely affectionate and more interesting than I’d have imagined. It featured malls from all across the country, charting their rise and fall with accompanying vintage promotional postcards drawn from the author’s private collection.

The site had a surprisingly large and devoted nationl fan base that had left many detailed and enthusiastic responses over each post, many of them personal recollections of people who had spent a big chunk of their childhoods and teen years at these places. Quite a few commentaries were by people who had worked at, or whose family had owned, stores in these locations. It was touchingly bittersweet.

This blog had been moribund for well over a decade now after a period of decreasing posts. Yet a lot of followers had continued showing up over the years to leave comments inquiring if the man who had created the site was OK, if he was ever going to post again or if anyone knew him and what had happened to him. The reactions ranged from bemusement to genuine concern to even a few surprisingly angry comments.

Going backward through the postings I’d found one about the mall I’d just visited and read how the author had grown up in the neighborhood and had many fond family memories of the place. I did an online search under his name and found an obituary for someone with the same name in my area whose accompanying adult photo bore more than a passing resemblance to the childhood photo the blog’s author had posted next to his name and personal info. The date of his death coincided within a year of the last posting so I felt reasonably certain this was the author. Even more coincidentally, the man had moved to my current city and his funeral was at a church I drove by every day.

I’d toyed with leaving a note, letting all the other readers know what I’d pieced together, in the comments section of the last post, which was still getting several inquiries a year. I decided not to do so out of respect for him, his family and their privacy. If his loved ones didn’t see fit to leave a message it didn’t seem appropriate for a stranger to do so.

Recently I’d changed my mind and decided I’d leave a brief comment and offer my condolences to the family. Someone with access to the site had deactivated the comments tab. I felt a tinge of regret and still think about all of the folks who’d shared their memories and feelings for something that had once been a part of so many lives and how many of them had expressed concern for the person who had brought them, in someway, together for a few years and who had then seemingly dropped off the face of the earth.

Not having discovered the site until after the fact I never had the same kind of connection with the author you had with yours, particularly since his blog was clearly more substantive. You, and, if appropriate, Smitty, have my sympathy.

It’s curious none of the other cultural websites I read has published a similar piece before you did here. It must be a very common experience these days. It’s a good example of why I come here every day.

Best wishes.

Oh, that’s the most heart-wrenching outcome. Thank you for being a repository of the memory of that particular subject matter expert.

As another daily visitor, I’ll wave through the screen at you, Byron. Please know you’ll be missed if you disappear.

Thank you for sharing this, Byron. I think a lot of us have had similar experiences at one time or another. Any reminder that we’re not as alone as we often think we are is a welcome one.

I have a similar rule when it comes to holiday cards: after 3 non-responses, I generally drop the recipient from the mailing list. Still, there are a few who were good friends, so I will keep mailing up to the day when a “Return to Sender” occurrence interrupts the stream.

And there are a few MIA websites that I continue to check, one that involved a lot of board wargames from the publisher SPI (Simulations Publications Inc.). The blog stopped for a hiatus, but the blogger announced his return. Right after, though, it just … stopped. Later comments showed that his eyesight had deteriorated to the point that he was having trouble reading on-screen materials. I still drop in occasionally and read old posts about SPI games that I loved to play, back in the day.

Another one that is still active on posting but not on comments is Shut Up and Sit Down, where the hosts continue to put up videos and podcasts about board games and card games of all varieties. But the comment streams have moved off to parts of the Internet (like Discord) on which I rarely venture. So I continue to enjoy the new material but I miss the old “What is everyone playing this week?” discussions.

After six months of silence, Stephen Pentz has returned – I love a happy ending!

Hurrah!!!