The Lost World

You may have heard about the recent statements made by Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos, a man who combines all the best qualities of Dr. Jack Kevorkian and Alaric the Goth in one natty package. As reported by Variety on April 28th, the streaming mogul declared that the precipitous decline in in-person movie attendance which began several years ago and has reached near-catastrophic proportions in the years following COVID is easily understandable; indeed, it communicates a clear message:

What does that say? What is the consumer trying to tell us? That they’d like to watch movies at home, thank you. The studios and the theaters are duking it out over trying to preserve this 45-day window that is completely out of step with the consumer experience of just loving a movie.

Relegating the theater experience that has defined the industry (to say nothing of wider American culture) for the past nine decades to the dustbin of history, Sarandos shined a dazzling light on our murky cultural landscape:

Folks grew up thinking, I want to make movies on a gigantic screen and have strangers watch them and to have them play in the theater for two months and people cry and sold-out shows… It’s an outdated concept.

Thank you, Ted, for clearing that up for us. I’m sure Scorsese and Coppola and Lee and Tarantino and Bigelow are happy to have the benefit of your sage counsel.

Lustily chomping his cigar and aggressively pounding his fist on the table (okay, I made that part up), the Netflix boss further said that the decline of movie theaters doesn’t “bother” him. He would be bothered, he added, if “people stop making great movies.”

Now I’ve seen the typical Netflix product, and you’ll forgive me if I think that Mr. Sarandos wouldn’t know a great movie if Bette Davis walked up with one in a steel film can and broke his nose with it.

Fasten your seat belt, Ted — it’s going to be a bumpy night!

Fasten your seat belt, Ted — it’s going to be a bumpy night!

If you sense a certain bitterness in my remarks, you’re right, and that sourness stems less from my distaste for Mr. Sarandos and his cavalier attitude towards something that I love than from my suspicion that he’s right, damn it. Much as I might regret it, it does appear that the kind of moviegoing experience that many of us have taken for granted for our entire lives is rapidly — and probably irrecoverably — becoming a thing of the past.

Some hard-hearted realists might say that mourning the decline of moviegoing (as in actually going to the movies) is as silly, pointless, and socially and economically regressive as bemoaning the fact that the buggy-whip industry isn’t what it used to be.

As a practical matter, that might be so, but I still feel entitled to mourn the loss. Why?

To be moved, whether you are frightened or thrilled, brought to tears or to laughter, is an experience that you can certainly have in your living room, alone or with one or two other people, but that’s a fundamentally different experience than feeling those same emotions in a room filled with many other people, in a place dedicated (I almost said consecrated) to undistractedly watching the movie and nothing else, a unique space where no one (ideally) is chatting, looking at their phone, constantly moving around the room, or pausing the action while they stroll to the bathroom or go to the door to get the Grubhub order.

The darkness, the size of the space and the close physical proximity of so many other people, the scale of the screen and the depth of the sound, the sustained, even relentless nature of the experience (to say nothing of the fact that because you’re leaving the house to do it, it’s something that actually requires a degree of planning), and yes, the cash outlay — even if the movie itself is a negligible piece of fluff, these factors all combine to make the in-person experience itself larger and more weighty.

Of course, every difference I just mentioned is, for an increasing number of people, a bug and not a feature. In that, Ted Sarandos is right. More and more people do seem to prefer streaming at home over the older way of seeing movies. I know, I know, who has the time anymore? Who has the money? And what about the kids? Anyway, how many movies are good enough to warrant going through all the hassle?

I can’t argue with any of these objections; I feel their force myself. And yet I think we’re going to lose something precious if going to the movies becomes some sort of boutique experience limited to a few large urban areas. Sarandros himself pointed to this as a likely future, saying, “If you’re fortunate enough to live in Manhattan, and you can walk to a multiplex and see a movie, that’s fantastic. Most of the country cannot.” (I don’t know where Ted lives, but apparently he pictures the rest of the country as some sort of vast Hooterville where people wander among the cornstalks, desperate for entertainment.)

The “concept” dismissed as “outdated” by Ted Sarandos has played a major part in my life ever since I can remember. My parents loved movies and “going to the show” was one of my commonest experiences growing up; we literally did it all the time, and I continued to go on my own or with friends as I got older. I have countless memories connected with seeing movies in actual theaters or at the drive-in, and the record of my moviegoing forms a kind of alternate history of my life; it’s probably the same with you. Here are a few of my random moviegoing memories, and they’re all the more powerful because they’re not just mine; they’re collective memories shared in one way or another with the hundreds of people who were with me in the theater at those moments, and with the millions who experienced the same feelings when they saw the same movies in their own hometown theaters.

(You will notice that all of these movies are from the 60’s and 70’s. I have had memorable theater experiences in just about every decade of my life — Dead Ringers, anyone? — but these came to my mind first. Given my topic, it’s probably no surprise that I’m feeling excessively nostalgic right now.)

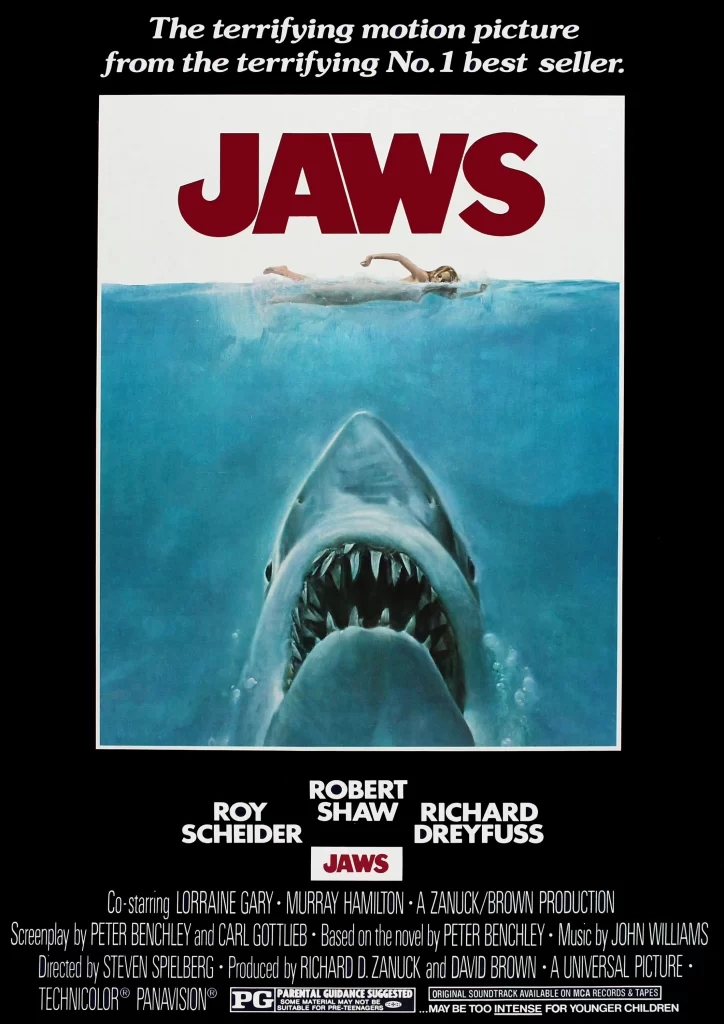

Summer, 1975. On vacation, visiting my cousins in Texas, we went to see something called Jaws. American movies and culture would never be the same. The shriek of delighted terror and terrified delight that burst from my fourteen-year-old mouth when that corpse’s head popped out of the submerged boat and scared the bejeezus out of Richard Dreyfuss, and me, and all the people surrounding me… well, I didn’t even hear myself, because my ears were too busy ringing from the identical sound that had just come from everyone else.

Quentin Tarantino has said that Jaws is the greatest movie (as opposed to the greatest film) ever made, because it delivers all those quintessential screaming/laughing movie pleasures more perfectly than anything else that’s ever been on the screen. If you were there in 1975, you can only agree with him.

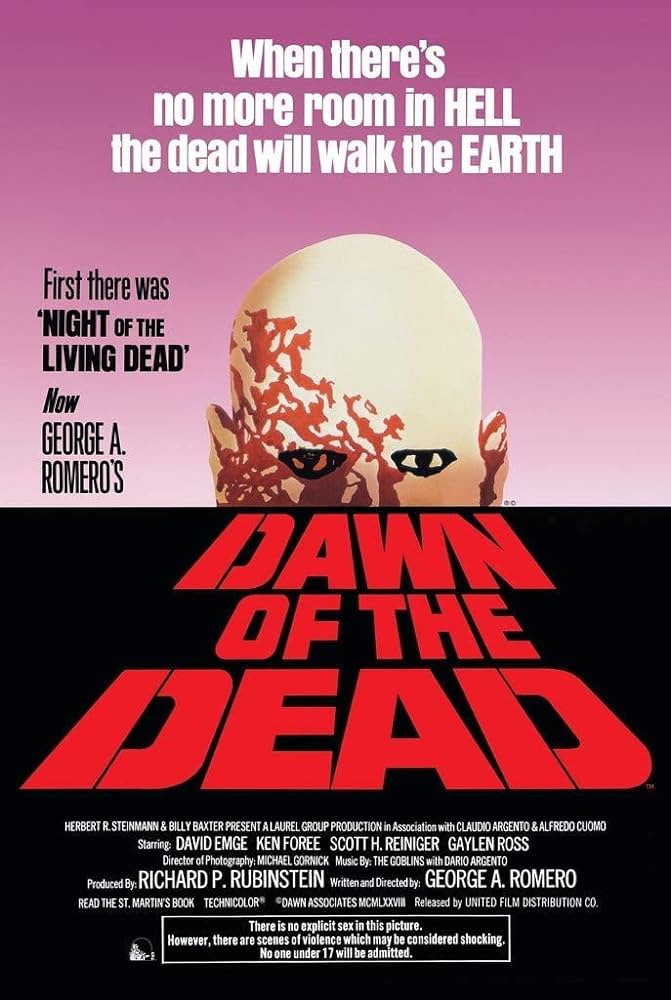

Spring, 1979. My buddy Eddy’s mom said she would take us to the show to see a horror movie. She loved horror movies; she had already taken us to the drive-in to see The Brood and The Corpse Grinders. That’s what I call a great mom. When my mom (also a great mom) heard that Ruth was going, she said that she would join us. I told her that she really didn’t want to do that; the movie we were going to see was called Dawn of the Dead and it was not a Vincent Price campfest, which was what she was expecting from a horror movie. “You don’t understand, Mom — this movie has zombies that eat people!” She tsk-tsked me and insisted on coming along.

Five minutes in, in an apartment building infested with the living dead, a woman spots the shambling corpse of her husband; she runs up to him and embraces him, whereupon he takes a huge bite out of her neck as the blood gushes by the gallon. That woman was no more shocked than my mom, who grabbed her purse, stood up, and walked out of the theater. “I told you!” I shouted as she exited.

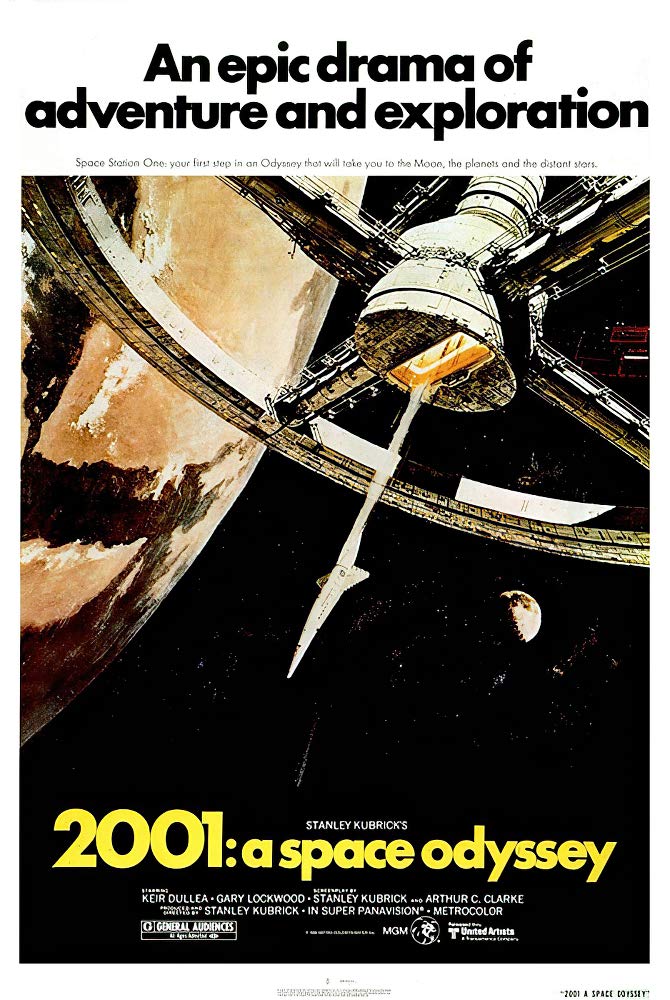

Spring, 1968. My mom gave me a day off from school. Why? She was going to drive me into Los Angeles so we could see 2001: A Space Odyssey at the fabled Cinerama Dome. (I told you she was a great mom.) She had told my teacher the day before that it would be “very educational.” The enormous curved Cinerama screen, the eye-popping special effects and overwhelming sound, the rapt enthrallment and utter bafflement of the audience — it has all stayed with me to this day.

As stunned people stood around on the sidewalk afterwards, there was a steady chorus of “What does it mean? Do you know what it means?” “I know what it means!” I recklessly piped up. As all those pairs of adult eyes focused on my seven-year-old self, I realized that I should have kept my big mouth shut. I didn’t know what the movie meant; I only knew that I had just had one of the greatest days of my life, and that I loved my mom.

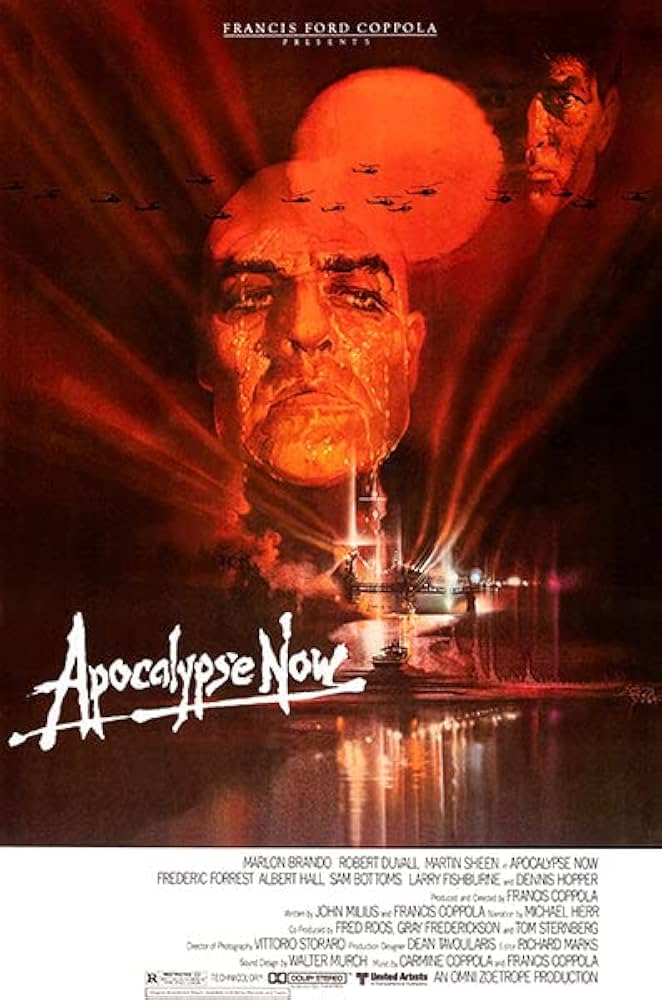

Fall, 1979. At the Cinerama Dome again, my friend Sutton and I arrived at the last moment to see one of the first showings of Apocalypse Now, and the only seats left were in the first couple of rows. The Dome’s screen was eighty-six feet wide and thirty-two feet high; from our seats, it was like crouching at the foot of Mont Blanc. When the movie opened with a napalm strike, I felt like every millimeter of my optic nerves were on fire, and during the “Ride of the Valkyries” helicopter strike I crouched in my seat to keep from being eviscerated by a mortar round or decapitated by a helicopter blade, and I knew that everyone else in the theater was doing the same thing, even those who had more rational seats than we did (I told Sutton we should have left home earlier).

Every person in the audience knew that they were seeing something beyond the realm of the normal; we were witnesses to an outrageous, crazily ambitious, magnificent once-in-a-lifetime folly that no one there would ever forget. It was probably my supreme experience at the movies, and it wouldn’t surprise me if a lot of the people who were there that night almost forty-six years ago look back and think about it that way too.

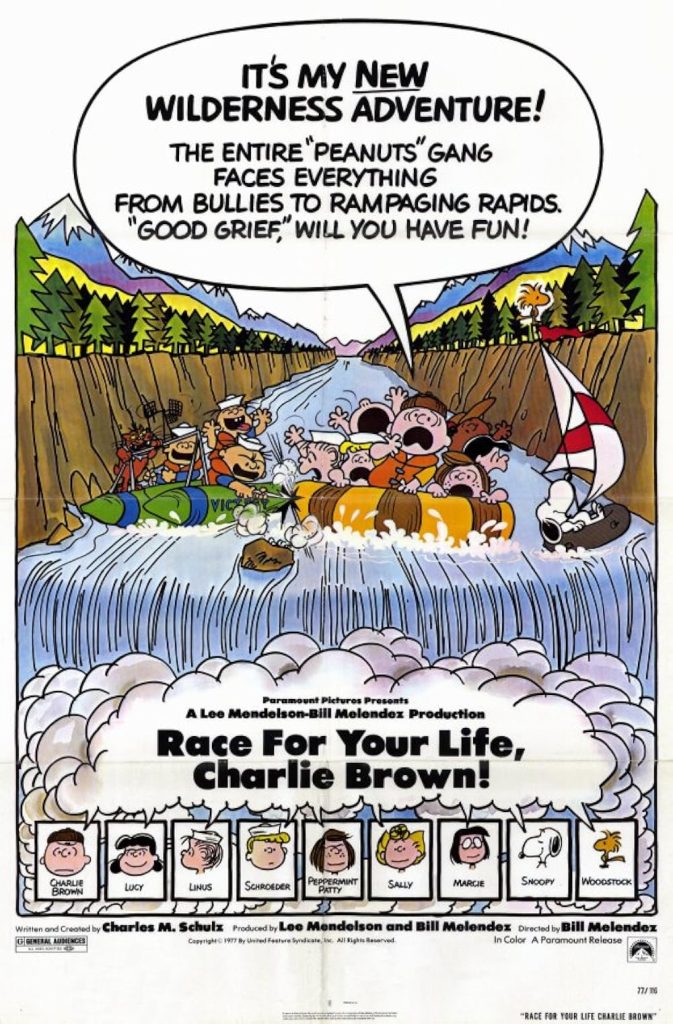

One more. Fall, 1977. The movie is, believe it or not, Race for Your Life, Charlie Brown! This time Sutton and I left in plenty of time to get decent seats, and anyway, we didn’t have to drive as far to get to the theater. (The Cinerama Dome usually didn’t book Charlie Brown movies.) We had a Saturday with nothing to do and the only thing showing was this Peanuts movie. Well, why not? The theater was full to overflowing with kids — I didn’t see an adult in sight. We two high-school boys were apparently the oldest people present. Clearly this mediocre cartoon was a golden opportunity for parents to dump their spawn for a couple of hours and have a little time for… well, other stuff.

Things held fairly steady until the lights went down, and then pandemonium reigned. You’ve read Lord of the Flies? It was like that. The air was instantly full of flying popcorn boxes and other trash, and the soundtrack was drowned out by an insane cacophony of laughs, shrieks, yells, catcalls, arguments, profanities. You couldn’t see the movie; you couldn’t hear the movie. The aisles were filled with kids running up and down, falling, rolling, jumping, kicking, crashing. One kid sitting several rows forward took umbrage at something the urchin sitting directly in front of us said or did and came flying from his seat, and jumping astride the offender, pinned him in place and started whaling on him as the surrounding kids cheered; it was like having a ringside seat at Ali-Foreman. We were too stunned to intervene (others quickly did), and we bolted for freedom as soon as the final credits rolled, happy to escape with our lives, but I have never forgotten that kiddie matinee; it permanently darkened my view of human nature and blighted my belief in the possibility of building anything lastingly good in this world. And all it cost me was, what? Two bucks and a little gas money? Now that’s what I call a bargain.

Beat that, Ted Sarandos.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Writ in Water: V.E. Schwab’s The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue

Hi, Thomas, thanks for another insightful essay! To your thesis, the movie-going experience is indeed nonpareil and I echo your thoughts about its ability to create lasting memories…but, as the media scholar Marshall McLuhan pointed out in the 1960s-70s, new types of media change the way people look at the world. Cinema was what he called a ‘hot’ medium, totally engaging one’s senses in exactly the way you describe, whereas TV is a ‘cool’ medium, working well in an environment where people could repeatedly look away and return to it without feeling the same sense of loss. One of his other key points was that different media rewire the brain to process information differently, referencing the way our forbears who grew up on print actually thought differently than those of us who grew up with a TV set in the house. (I was fortunate enough to spend some time in the 70s with Harlan Ellison, who bemoaned the fact that the TV generation had had their imaginations crippled by not being given the chance to visualize radio dramas as he did growing up.) McLuhan’s last writings were about constant information flow (i.e. online) and how it would change the next generation, leaving their parents wondering how they could function in such a hectic and all-encompassing environment…That said, I’m afraid our culture’s last cinema ship to Valinor has sailed…

I think you’re right about the moment having passed, Bill, for all the reasons you give, but it’s no fun when it’s YOUR moment that has passed.

I too was lucky enough to be present a couple of times when Harlan Ellison was ranting; I only wish we could have heard what he would have said about Ted Sarandos. It would have melted titanium!

I’m deeply impressed that you remember the actual movies you were watching for these experiences. For my family, it was always the experiences *around* the actual movie that made theater-going or drive-in-going memorable.

For the drive-in, there were two or three memorable events/circumstances that I couldn’t pinpoint which double-feature we saw when they occurred. There was always the pre-movies run to the grocery store to get dinner sandwiches and movie snacks, but there was a surreal evening when my parents decided to splurge– my savings-oriented father told me I didn’t have to choose between pretzels and cheese-puffs, oh, and let’s try that new nacho chip flavor while we’re at it, of course we have to get some salt’n’vinegar potato chips (you know how your Mom loves that one brand) and what do you mean, [sibling], that you’ve never tried pork rinds or Funyuns? Into the cart with it all! That was also the one time we bypassed the fruit section entirely and instead of getting apples and clementine, we went straight to the cookie aisle. There, my nutrition-specialist mother engaged in a serious discussion with me on the relative merits of Milanos vs. Chessmen (we did get both), talked about her memories of Nilla wafers (a box was purchased for demonstration purposes), we got both regular and double-stuf Oreos to see if there really was twice as much filling, and someone uttered the line, “You’ve never had Easy-Cheez? How are you so deprived? You’re going to love this.”

There follow vague composite memories of getting parked, waiting for the sun to go down while talking about the next day’s schedule of summer swimming classes, etc., then sitting crammed cheek-to-cheek with my sibling for two hours as we peered between the front seats, crouched low to see the entire screen through the front windscreen (heaven forefend that the top strip of the movie be blocked by the rear-view mirror). Then there was that one time my sibling did not judiciously sip at a drink, and started begging to go to the bathroom at the climax of the first movie. My parent begged my sibling to hold it until the credits, and the moment the text started rolling, a force of nature ripped my sibling out of the car by one arm, and they were running an Olympic sprint across the gravel, hurdling over the hoods of other vehicles, narrowly dodging the old speaker poles, my sibling trailing in the air like an anemic kite, as my parent tried to beat out the other parents who were a bit slower off the mark. I think they ended up fourth in line out of hundreds, to used the cinderblock bathroom.

More composite memories of dancing intermission refreshments cartoons, and second features that were somehow never as good as the first movie, but we stayed anyway because we had paid for the tickets and the grocery store snacks weren’t gone, yet. Then, after the credits rolled again, it was time to ease out of the spaces and into the driveways without playing bumper-cars. My father generally controlled his language around us kids, but this was the time he got colorful and nobody yelled at him for it. People were being particularly obnoxious about cutting in and jumping aisles, this one time, so getting out of the drive-in took exceptionally long, and we counted up a record number of cars (12? 13?) that had to get a jump-start from the theater because of battery issues. That was the only time that tension evaporated like dry ice the moment we got ONTO the highway.

For theater-going… hmm. Well, when my sibling and I were sub-12, my mother made a point of taking us out to do something when my father went away on a business trip, so that we wouldn’t notice that someone was missing and get anxious. That usually meant either dinner at the two-storey McDonalds with the triple-decker indoor playground that had the kind of elysian ball pit that could only ever have been built pre-COVID, or a trip to the movies. Remember, my mother is a nutrition enthusiast, so at the movies we usually got one popcorn bucket to share, and either three kid-sized drinks or one adult-sized drink to share. I remember the betrayal of my fingers hitting the bottom of the popcorn bucket with a bongo thud and discovering that someone else (not me– surely not me!) had eaten my share of the popcorn. I remember the swiftly more watery flavor of the soda sipped throughout the movie as the ice melted. And I remember that one again-surreal time that instead of the popcorn counter, my Mom led us to the pick’n’mix candy station in the lobby and bought us each a solid pound of our own blend of candies. I kept trying to figure out whose birthday it was, but it wasn’t anyone’s, just one of those red-letter days. That candy lasted me a week.

And then there was the drive home. The drive home from the movies was the very best. Whether Dad was with us or not, the drive home was when the whole family started quoting funny lines from the movie we’d just seen, vying to make each other laugh louder, longer, or more. Reliving the movies on the way home was more fun than seeing them the first time! And we could always tell if the movie was bad because only one or two of us could come up with a quotable line and the rest of the drive was quiet or a conversation about something other than the movie. Once, the quoting got so fierce and funny, Dad had to pull off to the side of the road until he got the tears out of his eyes from laughing so hard and could see again.

I only remember what movie I saw once, and that was because we watched “Air Force One” with a bunch of my friends the day before I made my first flight across the Atlantic alone. Certain young SFX YouTubers may now consider the plane’s demise in that movie to be about as realistic as the claymation in the original “King Kong,” but at the time it was pretty scary.

If theater movies go back to being an event as special as live plays, I don’t think it will be the movie bit of the experience I’ll miss. It will be the drive home. My family recently got together to stream the premier episodes of the “Murderbot” series (we all agreed that it was an excellent interpretation; we also all agreed that our own brains do a better interpretation), and somehow, throwing quotes while working together to make dinner afterwards does not have the same punch as when strapped into two cubic yards of the same space together.

Seeing a movie at the drive-in was a less frequent experience for us than seeing one in a theater, but I do remember seeing Planet of the Apes and Bonnie and Clyde at the drive in with my mom and sister. I fell asleep right before the end of Bonnie and Clyde and didn’t get to see the miscreants chopped into confetti by machine gun bullets. When I woke up, I was pissed!

Aw, man! You missed the best part! At least with your mother in the car you probably didn’t wake up with peanuts stuffed up your nose as “penance” for falling asleep.

Maybe there will be one other part of the theater-going experience I will miss: the staff interactions. Last month, I treated myself to “The Amateur,” which turned out to be one of those rare movies I enjoyed more than the book. It was a weekday matinee, so I had the entire theater to myself. After the movie, one of the ushers came in during the credits to soothe his PTSD after cleaning up yet another class-cutters’ chicken-rider-pocalypse in “The Minecraft Movie” next door by sweeping up a meager three or four kernels of popcorn, and we ended up geeking out together over how authors name their characters. Where else do you meet someone who makes his way back and forth across the country by ushering in a chain of movie theaters, than at a movie theater? It was fascinating, and left me pondering hypothetical theater-nomad lifestyles.

I grew up in a working class family of six during the late sixties and early seventies. Going to a movie theater was a rare luxury. We did see a fair amount of movies at the drive-in but even then my brother and I had to hide under the station wagon seats until we had passed the ticket booth to make it affordable.

The “ABC Movie of the Week” was our version of the weekly trip to the movies and while I have many fun memories of those films (and some of them weren’t bad) even as a kid I could see the qualitative difference between television movies and the older theatrical films that played on both the networks in prime time and on the local stations’ afternoon “Million Dollar Movies.” When I look at Netflix movies I still see just a TV movie. Regardless of the talent and expense there remains a discernable tonal and textual difference. It’s a subliminal quality and a hard-core moviegoer can sense it intuitively.

Even disregarding (if you can) the fact Netflix dictates exactly what kind of digital cameras and lenses its filmmakers use to make their movies look less crappy after all the compression, they still feel not just different but worse than even a second-rate Hollywood movie. You can tell the bar has been lowered and recent revelations that Netflix is telling writers to dumb down their scripts only confirms this.

I was raised on television movies and do think the medium does have its strengths, particularly the intimacy of curling up with a movie or show at home. Even then, I have experienced something similar sitting alone in an uncrowded theater which, coupled with the visceral impact of a giant screen and richer cinematic language of a film specifically shot for the theater.

Netflix built its audience by offering them a broader catalog than their local Blockbuster. Now they are now merely subsisting on the laziness of your average American family who are increasingly content to rot on the couch watching something, anything, over getting off their asses, going out into the world and risking 10 bucks and two hours of their lives on a movie experience that could enthrall and enrich them in a way the glass teat could never do.

Billy Wilder once observed that one person sitting in a movie theater may be an idiot but a thousand idiots were a genius so he never talked down to his audience. “Let the audience do the math and they’ll love you,” he famously said. Ted Sarandos now has the characters in his “films” actually explain what happened in the scene before and what’s going to happen in the next scene because their research shows that their audience is too preoccupied staring at their phones to follow whatever is playing in the background (yes, this is really happening).

By the time I was in high school my dad was making good money and we could suddenly go to the movie theaters and it was a revelation. I’d seen “2001: a Space Odyssey” at the drive-in in 1968 and while even that viewing rocked my little world nothing matched the experience of seeing the film again upon its 1974 re-release in 70mm on a giant, curved Cinerama screen. I literally felt weightless for days afterwards. From that moment on I was a theatrical junkie and my television watching plummeted to almost nothing where it would have remained had it not been for the home video revolution (and I’ll take my Blu-ray collection any day over Netflix’s ghetto of a film selection). I can also say that going to college in the late seventies and early eighties, when there were so many cinema guilds on campus that I went to the movies three to six nights a week, was one of the greatest educational experiences of my life.

I did quit going to the theaters for almost five years after COVID, at first out of health concerns, then more because of the dire state of contemporary film coupled with the insufferableness of the work-from-home crowd who no longer know how to act in public. I finally started going back this year, forsaking the cineplexes (that I’ll NEVER go back to) for the four single-screen theaters I’m fortunate enough to live within an hour’s drive of, all of which focus on classic, independent and international films. Most recently I caught “2001” again, in 70mm, in Detroit in a beautifully restored movie palace with a packed audience, most of them young people and all of them giddy with that unique, timeless joy that only going to the movies can evoke.

I don’t doubt that Ted Sarandos, clueless cineplex owners and that great, shapeless slug of a society called the American public will further cripple movie theaters but they won’t be able to kill it. There’s over a century’s worth of great films already out there (and a scattering of decent new ones) and they’ll always be a proportionally small but fervant audience eager to discover and celebrate them.

For the record, Ted, the theatrical experience isn’t dead, you are.

For me, cliche though it be, the most vivid memory is of visiting my grandparents in California in summer of 1977 and my few-years-older cousin saying, “Hey, there’s this movie playing that you HAVE to see,” and then sitting in the theater and watching the Imperial Star Destroyer rumble overhead for what felt like fifteen minutes and right there, at that moment, everything had changed forever.

And yes, I’ll be going to the new Mission: Impossible in the theater tomorrow despite the fact that the movie itself will be overlong and that when I factor in transit (I take the bus) it’ll be probably a 6+ hour investment of my time.

Having said which, while on the one hand I think Sarandos is a heathen, on the other hand, I also can’t support Francis Ford Coppola when he pulls the plug on any streaming or physical releases of Megalopolis because he feels that it should ONLY be seen in a theater on a big screen, which in practical terms means nobody in the entire world will ever see that movie again (well, I mean, not LEGALLY).

Oh, and for me, the glory days of Netflix were actually from about 2000-2010, when they were still sending discs in the mail and when their catalog consisted of EVERYTHING from brand-new blockbusters (if you were patient) to classic 70s cinema to obscure Hong Kong action flicks to silent black & white films of the 1920s.

It’s funny, but for the life of me I can’t remember when or where I first saw Star Wars, but I do remember waiting with college friends in a loooooog line in L.A. to see The Empire Strikes Back, and not being disappointed.

I recently discovered that my childhood hometown’s public library has access to a full set of the local newspaper’s archives, so it’s been fun going back and trying to figure out exactly when (well, to within a day or two) I saw some movies for the first time. We were a smaller town with not many screens, so at least when I was young, we tended to not get titles until several weeks or even a couple months after they released — like, although both Black Hole and Star Trek: The Motion Picture are 1979 releases, I didn’t see them until early 1980 (long after I’d read the novelizations for both of them).

“Beat that, Ted Sarandos.”

Hmm, Mr. Sarandos was born in 1964, so he would be 12-13 at the time of your viewing “Race for Your Life, Charlie Brown”. And he does seem like the type of person whose loudly stated opinions would provoke fisticuffs. Maybe he was the urchin in front of you who was taking a beating. Could explain his aversion to the movie theater experience.

And your mother took you out of school to see “2001: A Space Odyssey”? Truly a wise and loving mother!

Eugene, you have provided the perfect capper. Thank you, sir!