Writ in Water: V.E. Schwab’s The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue

How many times have you heard (or even repeated) the old adage, “Be careful what you wish for?” Of course it’s a cliché, a commonplace beloved of parents and primary school teachers the world over, but such chestnuts sometimes actually contain the distilled wisdom of the human race, and you ignore them at your peril, as is demonstrated (or not, maybe) in Victoria Elizabeth Schwab’s 2020 dark fantasy, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue. It’s a spirited, stimulating read that gives you something to think about.

The story begins in a small French Village, Villon-sur-Sarthe, on a summer evening in 1714. A young woman named Addie LaRue is “running for her life.” Her family has affianced her to an inoffensive but crushingly dull young man. Addie, however, doesn’t want her life to be yet one more colorless copy of the bland existence that her mother (and her mother before her, and her mother before her, and her mother before her…) has led.

Addie has occasionally gone with her carpenter father (who she is closer to than she is to her unsympathetic mother) on business trips to a neighboring town, and these all-too-rare glimpses of the world outside have sparked something in the young woman. She wants to see Paris, she wants to see the world, she wants to go where she will and love who she will. Looking around the well-known, changeless streets of her home, they look more and more like the bars of a prison; she knows that’s not what she wants. She knows she wants more.

Addie’s dreams and ambitions have been (somewhat equivocally) encouraged by an old woman of the village, Estelle Magritte, who is considered by some to be a witch. Estelle talks to Addie about the ancient, elemental, unpredictable gods of the fields and the forest, but she gives the girl one piece of very serious advice:

The old gods may be great, but they are neither kind nor merciful. They are fickle, unsteady as moonlight on water, or shadows in a storm. If you insist on calling them, take heed: be careful what you ask for, be willing to pay the price. And no matter how desperate or dire, never pray to the gods that answer after dark.

It’s counsel that Addie might have been better off heeding.

Fleeing her wedding, Addie plunges into the woods; as she goes deeper into them, the voices of her pursuing family grow fainter and fainter until they disappear. Addie falls to the ground, exhausted, and desperately begins to pray to the only source of help that she can think of, the old gods that Estelle has told her about, but more time has passed than she thinks; she doesn’t realize that the sun has set and that she is calling into the darkness.

Her plea is answered by one of the capricious, compassionless gods that Estelle warned her against, and though he may be inhuman, he at least has an ironic sense of humor, as he comes in the form of the fantasy lover that the lonely Addie “has conjured up a thousand times, in pencil and charcoal and dream.”

Congratulations — you are now the proud owner of a Ford Fiesta! All it will cost you is your soul!

Congratulations — you are now the proud owner of a Ford Fiesta! All it will cost you is your soul!

After the being asks if she is prepared to pay the price for his services, Addie makes the fatal promise, “I will pay anything.” The entity, be it god, devil, or something so entirely other that it cannot fit into either of those common categories, asks her why she is willing to do this. The girl replies with what amounts to her manifesto:

“I do not want to belong to someone else,” she says with sudden vehemence. The words are a door flung wide, and now the rest pour out of her. “I do not want to belong to anyone but myself. I want to be free. Free to live, and to find my own way, to love, or to be alone, but at least it is my choice, and I am so tired of not having choices, so scared of the years rushing past beneath my feet. I do not want to die as I’ve lived, which is no life at all. I –”

The being (which she will soon name Luc) cuts her short. He’s not interested in what she doesn’t want. Can she tell him what it is that that she does desire? That’s easy; Addie wants more time. Luc puts the wish into words for her — “You ask for time without limit. You want freedom without rule. You want to be untethered. You want to live exactly as you please.”

“Yes,” Addie says… but Luc declines the deal. After all, what’s in it for him? He gives her life unending, and he gets nothing? It’s hardly fair. And in that moment, Addie hears again the voices of her family and the other villagers, searching for her, growing louder, coming closer. And in that last moment, she recklessly stakes everything. “You want an ending,” she says. “Then take my life when I am done with it. You can have my soul when I don’t want it anymore.”

Deal.

The rest of the book shows us what kind of life Addie has purchased, and it does so with a forward/backward structure that alternates chapters showing that life in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries (she spends most of the early eighteenth-century chapters discovering exactly what sort of covenant she has entered into), and chapters set in New York City in 2014.

What is the nature of the bargain Addie has made? (Of course, Luc’s deal comes with small print — there’s always small print.) As is common in such transactions, it soon becomes clear that Luc has given her exactly what she asked for. She wanted complete freedom, a radically unfettered life; she wanted no obligations to anyone, and her “benefactor” has found the perfect way to grant her wish.

Addie is free to go where she will, free to do what she wants, free to spend her time in the company of whomever she pleases, and people are drawn to the beautiful, bewitching young woman with the constellation-like pattern of seven freckles on her face. They love her when they’re with her. But when she leaves the room for more than a few minutes, or when they do, or when they fall asleep…

They completely forget her; she vanishes from their minds and memories as thoroughly as if she had never existed. In an especially painful twist, people are unable to even speak her real name.

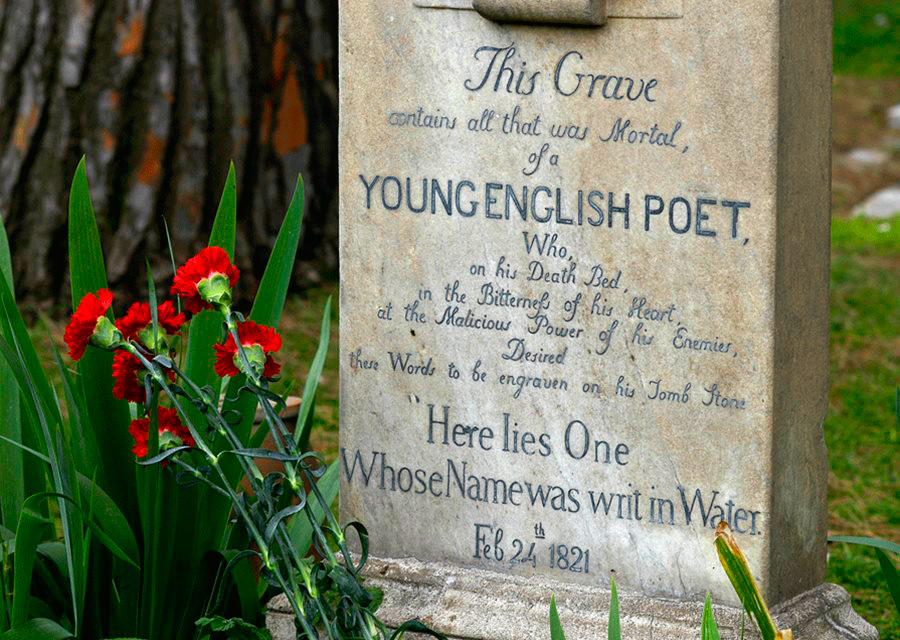

As the years pass and Addie travels far and wide, she leaves her narrowly circumscribed life in her stultifying little village far behind, and she indeed sees the world — but the cruel nature of her bargain makes it impossible for the world to see her. She finds herself living a rootless, utterly transitory existence which is, in the words of John Keats’ pathetic epitaph, “writ in water.”

Through all these restless centuries, Addie lives by theft (which bothers her, but what else can she do), finds temporarily vacant houses or apartments to stay in for a day or a week, and establishes relationships as transitory as the lives of mayflies. For the first few decades, Luc appears every year to see if Addie is ready to surrender her soul. She always refuses, even as she finds herself looking forward to these visits — who else can she have a real conversation with? Luc’s visits eventually become much more sporadic (despite the hints of a growing and ambiguous attraction between the two, especially on Luc’s part; perhaps it is not good for even a god to be alone). Neither the human nor the inhuman are in a hurry; after all, they both have nothing but time.

Even in the midst of her exile, Addie takes heart from knowing that she has managed to leave some subterranean traces in the world after all, in the works of artists she has briefly known. Luc has been unable to prevent a ghostly record of Addie from appearing in a painting here, or in a song there. This helps her to hang on despite her unassuageable weariness. (That, and she’s just damned stubborn.)

The story makes a major shift in the second half of the book, when, in present-day New York, Addie meets a young man named Henry who works in a used bookstore. He is the one Addie has been waiting hundreds of years for; miraculously, he can remember her. (Addie discovers this when she tries to steal a book.)

Addie and Henry quickly fall in love, or at least, Addie sees that as a real possibility. (For her, he’s the only game in town.) But why is he different? Why can he remember her? The answer turns out to be simple — he, too, has made a deal, and is therefore living outside the boundaries of normal human existence.

Henry’s dilemma was the opposite of Addie’s — the youngest son of a prosperous, successful family, he always felt overlooked, ignored, invisible. No one ever saw him for who he really was. When he proposes to a young woman he has fallen in love with, she turns him down, making it clear that he’s nice and all that, but ultimately he’s not all that important to her. Shattered, Henry decides to commit suicide, but before he can complete the act, Luc appears with an offer: instead of being a person people see through, Henry will become a man no one can miss. Whenever anyone looks at him, they will see whatever they most desire. To everyone he meets, he will be the most important person in the world.

You see the problem, don’t you? Henry, of course, doesn’t, and he accepts the deal.

Now when people look at him, speak to him, have sex with him with glaze-eyed delight, they’re not really seeing him at all; they’re seeing an embodied fantasy that has nothing at all to do with the actual Henry Strauss, and the young man ultimately finds himself more even isolated and desolate than he was before.

This why Henry can remember the ephemeral Addie and why Addie can see the actual Henry — the bargains that they struck perfectly complement each other; their hells dovetail seamlessly.

One difference, though, is that Henry didn’t drive a very hard bargain; his contract isn’t open-ended, and when he meets Addie, the bill is about to come due. Henry has just over a month to live.

A few days before Henry is to die, Luc appears to Addie for the first time in thirty years. Does he know that he finally has her where he wants her? Maybe so, because Addie then finds out the terms of Henry’s contract, and having at last found someone she can willingly sacrifice herself for, she proposes a new bargain: she asks Luc to give Henry (who is “the one piece of her story that she can save”) his life back.

If Luc does this for her, Addie tells him, “I will be yours, as long as you want me by your side.”

Done.

The story ends two years later with Addie browsing in a London bookstore. She hears a customer ask for a copy of a hot new novel that’s making quite a stir. Written by an anonymous author, it is titled The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue.

Finding a copy herself, Addie tremblingly looks at the dedication page; it bears just three words: I Remember You.

Addie knows then that she has won her gamble, and when Luc appears and they walk out of the bookstore together, she thinks that the god who seemingly brought her to bay has been too clever by half. She has an unlimited amount of time in front of her, all the time in the world, time enough to work on Luc as he worked on her, time to “ruin him,” to “break his heart,” to “drive him mad, drive him away.” All the time there is, to make him willingly “cast her off.”

Then, and only then, Addie LaRue will have what she desperately desired so long ago. Finally, she will be free.

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue is an engaging and highly imaginative book, but I do have a couple of quibbles. Addie’s discontent and (especially) the way she thinks about it and acts on it seem more like that of someone born at the end of the twentieth century than of someone born at the end of the seventeenth. Truly entering into the thought-world of a person of such a radically different era is a difficult task (perhaps especially so in our highly “presentist” age) and I can’t say that Schwab has entirely pulled it off. (I also think that kind of portrait wasn’t something she was really aiming at.)

Also, I was less than enthralled with the second half of the book’s “current-day” sections, which largely became one long episode of Young Brooklyn Romance, which, if it isn’t a hit new Netflix series, probably soon will be. In any case, it’s not the sort of thing that winds up at the top of my watch list. With the entrance of Henry, the book moves from things I’m more interested in (explorations of what freedom is and what it’s for, and of the relationship between community and identity — to what extent do we even exist except in relation to other people?) to something I’m less interested in (urban love among the achingly trendy). I say this understanding that I’m not a part of the target demographic of either the novel or the hypothetical show — and by the way, if anyone uses my title, they had better pay me.

Those complaints aside, the story Schwab tells is consistently engaging and entertaining, and at times even thought-provoking. The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue gains much of its power from being a lively new variant on a very old tale and by maintaining its connection with countless myths and stories that have gone before; the novel contains echoes of Faust, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Wandering Jew, The Flying Dutchman, The Devil and Daniel Webster, and Peter Pan, to name just a few, and Addie can stand unembarrassed in their august company.

Two more recent stories that Addie LaRue also reminded me of are Lolly Willowes, Sylvia Townsend Warner’s 1926 novel of a woman who becomes a witch and sells her soul to the Devil in order to do exactly what Addie wanted — live her own life. Warner was a major writer in many different modes and Lolly Willowes is a masterpiece of double-edged irony, but even though Schwab’s book operates on a less profound level than Warner’s, it’s still not a stretch to speak of them both in the same breath.

Also, Luc strikes me as being at least a cousin of that malevolent aristocrat of Faerie, the Gentleman with the Thistle-Down Hair of Susanna Clarke’s wonderful Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, though the Gentleman is frightening in ways that Luc can’t begin to match. (No person in their right mind would contemplate for an instant having a relationship, romantic or otherwise, with the Gentleman.)

Reading The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue and thinking about the questions it raises brought to mind something that Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, once wrote:

People do not realize just how much they are putting at risk when they don’t accept what life presents them with, the questions and tasks that life sets them. When they resolve to spare themselves the pain and suffering, they owe a debt to their nature. In so doing, they refuse to pay life’s dues and for this very reason, life then often leads them astray. If we don’t accept our own destiny, a different kind of suffering takes its place… One cannot do more than live what one really is. And we are all made up of opposites and conflicting tendencies. After much reflection, I have come to the conclusion that it is better to live what one really is and accept the difficulties that arise as a result — because avoidance is much worse.

Addie challenges the status quo and pushes the boundaries of freedom and in doing so, she gets more than she bargained for… or does she? In making her initial deal, is she avoiding her destiny or accepting it? It’s possible to come down on either side of the question. It wouldn’t surprise me if one of these days, Schwab writes a sequel that gives us a more definitive answer.

I’ll definitely be there for it… but the world is wide and there’s no limit to places you can set a book, so can we stay out of Brooklyn? Please? I’d give almost anything…

Abandon all hope, ye who enter here

Abandon all hope, ye who enter here

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Life Lessons from David Cronenberg

That bargain sounds curiously like Faust’s deal with Mephistopheles.