Odd Old Indie: Night Tide

Growing up in Southern California in the 60’s and 70’s was a movie lover’s dream. Late night and weekend television in those days was almost completely given over to old movies, especially on the Los Angeles independent channels: KTLA channel 5, KHJ channel 9, KTTV channel 11, and KCOP channel 13.

The independent stations were especially prone to showing independent movies, small films that hadn’t cost much and hadn’t made much and could be acquired cheaply to occupy all the time that had to be filled until sign-off and the test pattern. Many of these movies were from the House of Corman (The Little Shop of Horrors, The Masque of the Red Death, Dementia 13), but most weren’t, and any night of the week you could watch a pulse-pounder like The Flesh Eaters, The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies, or Beast of Blood (once you had advanced — or descended — to Filipino horror movies you could consider yourself a schlock PHD.)

Most of these films were awful, of course (that’s how you wound up on channel 13 at two in the morning), but sometimes a (relative) diamond could be found among the ashes. One movie that I discovered during those years was Night Tide, an odd little indie that aimed a bit higher than the usual cheapie thriller. I was always happy when it popped up in the week’s TV Guide listings.

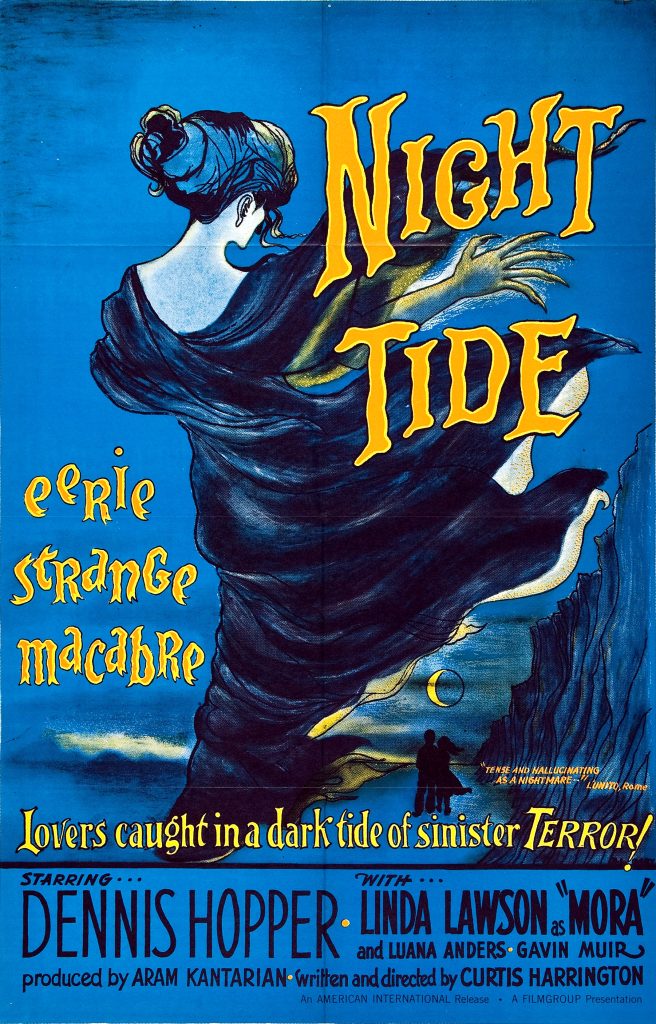

Made in 1960 and first screened in 1961, but not widely released until 1963 due to distribution confusion (it has a Corman connection after all, because it was released through Filmgroup, his distribution company) and directed by Curtis Harrington, it’s an offbeat film that has all of the expected deficiencies of a micro-budget independent movie along with some unexpected virtues. (It was supposedly made for $25,000, which wouldn’t even cover George Clooney’s carfare today.)

Clearly taking his inspiration from the series of nine horror films that Val Lewton produced for RKO in the 1940’s (Night Tide owes most to the first of them, 1942’s Cat People), Harrington (who wrote the script as well as directed) tells an ambiguous, poetic, melancholy story in an allusive, indirect way. Making a virtue of poverty, Harrington allows the viewer to fill in everything that is only suggested (because it would cost too much to show it), which was very much the strategy Lewton followed in making his underfinanced gems.

Night Tide is the story of a USN sailor, Johnny Drake (a twenty-five-year-old Dennis Hopper in his first lead role) and Mora (Linda Lawson), a young woman who appears as a mermaid in a boardwalk sideshow. (Most of the movie was shot just west of Los Angeles in Santa Monica.)

Strolling along a beachfront street one night, Johnny drops into a jazz club where he sees Mora sitting alone, raptly listening to the music. Struck by her dark beauty, Johnny asks if he can sit at her table to get a better view of the players. Mora agrees, but brushes aside the sailor’s attempts at conversation. While they are sitting there, a strange, black-clad, intense-looking woman comes up and speaks to Mora in a foreign language. The woman walks away, and Mora, visibly upset, rushes out of the club.

Johnny, desperate to make some kind of connection with this intriguing woman, follows Mora down the darkened street, all the while trying to persuade her to talk with him. Perhaps sensing a loneliness equal to her own and touched by his sincerity, Mora permits Johnny to walk her to her home above a carousel. She rebuffs his request to come upstairs with her, but she permits him to clumsily kiss her goodnight, and leaves him with an invitation to come back in the morning, when she will fix him breakfast.

When Johnny returns the next day, he first takes a look at the merry-go-round under Mora’s apartment, where he meets the ride’s operator and his granddaughter Ellen (Luana Anders), who both respond a little oddly when they hear that he’s there to visit the sideshow mermaid.

When Johnny goes upstairs, Mora greets him warmly and leads him through an apartment decorated with souvenirs of the sea, to a balcony overlooking the ocean, where they will have their breakfast. (Seafood, naturally.) During their conversation, the sailor and the enigmatic young woman shyly begin to get better acquainted.

Mora tells him about her job — “I wear an artificial fishtail and I lie in a tank that looks like it’s filled with water, and people pay twenty-five cents and come and look at me, and that’s how I make my living.” When Johnny asks her if she ever gets tired of it, she wistfully replies, “Sometimes — but it’s restful, anyway.”

When Mora asks Johnny to tell her something about his life, he tells her that he is alone in the world; his father left home when Johnny was just a boy, and when his mother died, he thought that the best way to get away from Denver, Colorado was to join the navy and see the world. “But I haven’t seen any of it yet.”

Then, as they are finishing their meal, an odd thing happens. A scavenging seagull swoops down on the table looking for scraps, and Mora takes it in her arms and gently strokes it and talks to it, and the wild creature seems perfectly calm and content. When Johnny asks her where she learned to do such a thing, Mora says that she doesn’t remember.

After their breakfast is done, they go down to the boardwalk and Johnny meets the man who owns the mermaid attraction and serves as its barker, Captain Samuel Murdock (Gavin Muir). He found Mora when she was a child on the Greek island of Mykonos, and brought the orphaned girl back to the United States as his ward. Murdock tells Johnny to drop by his house sometime; he will tell him some interesting things about his adoptive child.

Soon Johnny is spending every liberty with Mora, and even as they grow closer, the young sailor’s disquiet also grows, as he hears some strange things about his new girlfriend. Ellen (who is clearly attracted to Johnny) and others tell him that two young men who had grown close to Mora drowned in mysterious circumstances; the police are still investigating the deaths.

And one night on the beach, where people have gathered for a party, a curious thing occurs. A musician plays the bongo drums, and Mora begins to dance on the sand; as her movements grow wilder and more ecstatic, she looks toward the ocean and sees, standing silently there, watching her, the black-garbed woman who spoke to her in the jazz club. Johnny sees her too. Mora collapses in a swoon, and when Johnny rushes to her to see if she’s alright he looks around for the woman, but she is gone. The woman vanished n the few seconds it took him to get to Mora.

Increasingly worried, Johnny decides to visit Captain Murdock at his home in cement-canaled Venice, and as he nears the house, he sees the woman again. He pursues her, but she evades him in the maze of canals and bridges. When he arrives at the house, the captain gives him an effusive welcome, but soon adds to Johnny’s unease by telling him that he is in grave danger as long as he continues to see Mora, that the gentle-seeming girl might feel “compelled” to kill him. Before he passes out from drink, Murdock tells the disbelieving sailor that Mora is a siren, a member of the ancient race of sea people who lure men to their doom.

When Johnny tells Mora the captain’s story, she tells him that it’s true — “They are waiting for me to join them.” She believes that the strange woman who is following her is one of the sea people, “here to remind me of the time I must go to them in the sea.” Johnny’s scoffing at this absurd tale can neither shake Mora’s belief in her alien nature and her dark fate, or silence his own growing anxiety.

Visiting Mora after she finishes work one day, Johnny falls asleep on the couch while she takes a shower. He dreams that a towel-wrapped Mora walks out and sits by him on the couch, and looking down, he sees that her legs have turned into a fish’s tail; she is truly a mermaid, a creature not fully human. She leans over and begins to kiss him, and suddenly it is not the arms of a beautiful young woman that enfold him — he is entangled in the grotesque tentacles of a huge octopus, strangling him, devouring him. (This terrifying episode is probably Night Tide’s best-remembered scene.)

When Johnny awakens from this nightmare, he calls out to Mora but receives no answer. She has disappeared. Johnny follows her wet footprints out of the apartment and down to the beach. After frantically searching he finally finds her clinging to the pilings under the pier, barely holding on as she is battered by the waves of the incoming tide. As he carries her back to her apartment, she tells him that the sea people were calling her to them.

The next morning, Mora is strangely calm and later, after telling Johnny that the tides will be perfect (because the moon is full), she urges him to go diving with her at special place that she knows. (A few days earlier Johnny had visited a boardwalk Tarot reader who made ominous hints about his future due to the placement of the Moon card.) Johnny uneasily tries to convince Mora that a dive isn’t a good idea, but, unable to dampen her puzzling enthusiasm, he finally agrees.

Taking out a small boat, they make their dive (after Mora cautions the visibly nervous sailor to stay very close to her), and when they’ve gone down to the deepest point, Mora gets behind Johnny and cuts his air hose. As he desperately fights his way back to the surface, he looks back and sees Mora swimming away into the darkness. After waiting in the boat until long after her air would have run out, Johnny takes the boat to shore and stumbles back to Mora’s apartment, where he falls into an exhausted, troubled sleep.

There he has one last dream of this strange, ill-fated young woman — he sees her as a mermaid, sitting on the rocks with the waves crashing about her, an unreadable expression on her face as she regards herself in a mirror. When Mora turns and sees him, she slips into the churning water. Johnny reaches out and takes her hand, trying to pull her back up onto land, but he is not strong enough to overcome the immense power of the ocean’s pull, and a laughing Mora finally slips away from him and vanishes beneath the surface of the sea.

Later that rainy night, he wakes from this sleep, shaken and desolate, and walks to the boardwalk. Going into the mermaid exhibit, Johnny hesitantly looks into Mora’s tank, where he is stunned to see the body of the drowned girl floating face-up in the water, her hair streaming around her. She is still beautiful, even in death.

Captain Murdock (who found Mora’s body on the beach) emerges from the shadows with a gun in his hand and accuses Johnny of killing her, which the young man denies — “But I loved her.” “You loved her! What do you know about love?” Murdock replies. “I’ve loved her ever since she was a child. You did it and you must pay for it!” Murdock fires at Johnny but misses, and the shots bring the police, who take both men into custody.

At the police station a distraught Murdock makes a confession to a detective (and to Johnny — he asked that the sailor be present). When she was still a child, he began telling Mora that she was one of the sea people in the hope that it would keep her from forming close relationships with anyone else, and so prevent her from ever leaving him. Ultimately, even that didn’t keep Mora from wanting something more, and the captain killed her two boyfriends and made his ward believe that her inhuman nature was somehow responsible for their deaths; he just couldn’t bear the thought of losing the only person in the world he loved, the only person in the world who loved him.

Murdock’s “experiment in psychology” worked only too well; Mora “couldn’t face a recurrence of what had gone before, so rather than destroy the person she loved, she decided to embrace the rapture of the depths.”

The only thing left to clear up is the identity of the mysterious woman — was she an accomplice of Murdock, someone he had paid to follow Mora to remind her of her supposed evil destiny? The broken old man has never seen such a woman, never heard of her. She was part of no plan of his.

When Murdock is led out of the detective’s office, he gently pats Johnny on the shoulder, a sad little gesture between two men who will forever be linked by the loss of the woman they both immoderately loved.

The shore patrol arrives to take Johnny back to his ship, and Ellen is waiting at the desk to express her sympathy and to say goodbye. Maybe on his next liberty, Johnny can come by and take a ride on the carousel? The sailor smiles hesitantly and says that it seems like a good idea. As he walks out of the police station, the rain has ended, and a new day is dawning.

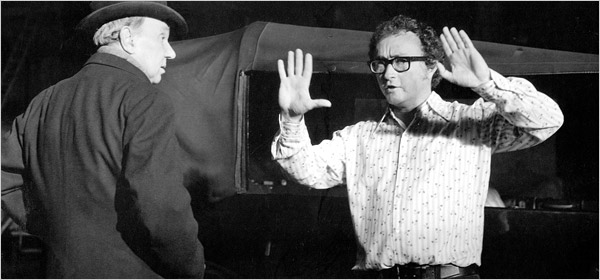

Gavin Muir and Curtis Harrington

Gavin Muir and Curtis Harrington

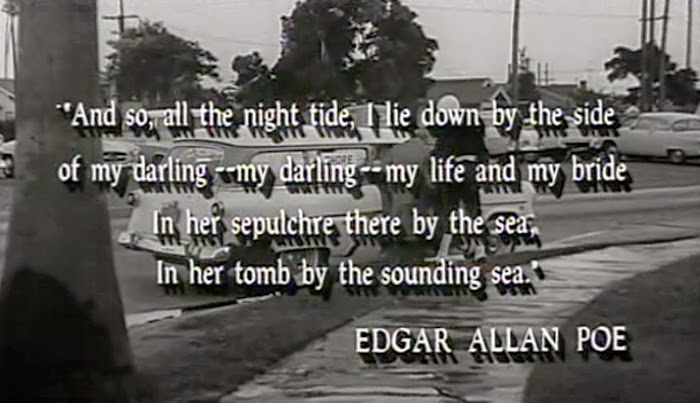

The film closes with the lines from Poe’s “Annabel Lee” that gave it its title: “And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side / Of my darling — my darling — my life and my bride, / In her sepulchre there by the sea — / In her tomb by the surrounding sea.”

So, what do we have here? Is Night Tide a brilliant achievement, a neglected masterpiece? You can judge for yourself (there’s a very nice print on YouTube, though there wasn’t several years ago when I bought my Kino Lorber Blu-ray), but it’s not necessary to go quite that far.

You don’t have to look very hard to find Night Tide’s defects. The story, as I said before (and as Harrington always acknowledged) borrows heavily from Cat People, which is a better, more original film, and even if you’re not familiar with the earlier movie, it’s not too difficult to see where the story is going (Captain Murdock’s big revelation isn’t much of a surprise); the dialogue is sometimes stilted, both in the writing and in the delivery by the actors, some of the supporting playing is erratic, and the mark of the low budget is visually evident in dozens of ways.

But many of these failings have a positive aspect, too. If you’re going to pick a model, Cat People is a strong one, and many of its virtues are evident in its successor, while the low budget compelled Harrington to stick to the commonplace in costumes and sets, giving the movie a much-needed grounding in everyday reality (while also permitting the director to concentrate on character rather than on special effects). Despite a few overtly arty touches, the black-and-white cinematography (much of which was shot at night), strongly conveys the darkness and moody ambiguity of the story. (The film’s flute-heavy jazz score by David Raskin is both a plus and a minus; sometimes it’s delicate, eerie, and just about perfect, while at other times it’s discordantly, distractingly obtrusive.)

Perhaps the film’s greatest assets are Dennis Hopper and Linda Lawson. Both were experienced television actors in 1960, but Night Tide was the first movie lead for both of them, and the awkwardness and uncertainty that are sometimes detectable in their performances actually suit their characters very well. Hopper is convincingly shy and callow (a “fair young man, innocent and searching” as the Tarot reader calls him); his yearning for human contact comes across as touchingly genuine. (At the beginning of the movie, Johnny has some pictures taken in an automated photo booth; he puts his hat on, takes it off, smiles, looks serious… and then tucks the pictures into his pocket and walks away. He has no one to give them to.)

Linda Lawson, despite not being gifted with a very expressive voice, nicely coveys a loneliness and a consciousness of being separated from “normal” people that matches Johnny’s intense desire to connect with someone; she makes the lost, doomed Mora a moving, tragic figure.

Night Tide uses its limited resources to try for something different than the usual rubber-monster-on-the-loose quickie; it’s a mood piece in which feeling and atmosphere are more important than plot, a poetic, offbeat combination of fantasy and horror and mystery, wrapped around an ill-starred, very human love story. In some ways it’s almost an amateur film, but it’s none the worse for that. (Remember that one meaning of amateur is someone who does something just for the love of it.) The movie has a unique flavor, sweet and sad, and for all of its (understandable and forgivable) deficiencies, it lingers in the mind; it gets under your skin.

You can always recognize a film that was truly important to the people who made it, and Night Tide is one of those; clearly, it wasn’t just another job to Curtis Harrington, Dennis Hopper, Linda Lawson, and the rest of the people who worked on it — it meant something to them. If you give it a chance — say late some lonely night — you might find that this old, odd little movie has come to mean something to you, too.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was The Eccentric’s Bookshelf: Michael Weldon’s Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film

I grew up in mid-Michigan during the same era as you. Because we could pull in the Detroit and Windsor stations we likewise had what seemed a wealth of channels at the time, many of which had both afternoon and late night movies not to mention the beloved CBS Late Show that was a Hollywood film history course in itself.

You nail the tone and merits of “Night Tide” perfectly. It’s not a great film by any stretch but if you discover it late some night when you’re alone (and feeling perhaps a bit sensitive to that fact) it does have a curious appeal. In that one regard it does channel the best Lewton movies which themselves found much of their power through an often haunting sense of aloneness which is something distinct from loneliness.

It’s certainly a film I’d recommend to anyone whose radar is attuned to curios like this although it is best discovered by accident when channel-flipping, an experience sadly rare in the streaming age.

Wait. Murdock gets to walk away? Implication being that the drowning of his ward and the grief that engenders is a ruesome-enough set of consequences? Implication being that the police determine Mora committed suicide after attempting murder-suicide?

…The end of this description is leaving me with the same sort of dissatisfied feelings that “The Ghost and Mrs. Muir” and “Casablanca” do. You must be right, the movie was deeply important to its creators, because I don’t think it’s possible to achieve that effect without commitment.

I guess Murdock doesn’t get charged with anything regarding Mora herself (I’m not sure what the charge would even be), but he’s definitely doing time for his confessed murders of her two previous boyfriends.

(I see that the fault was in my wording – I’ve changed “walks out” to “is led out.” Thanks!)

Oh, that feels just a bit better, then. Thank you for clarifying. There’s more justice there.

That sounds strikingly like some of Poul Anderson’s stories where a man is caught between an exotic and perilous woman, and one who’s a figure of domesticity. Though I suppose the trope is older than that; Victor Hugo has something akin to it in L’Homme qui rit, for example.

I think you’re right – the Mora/Ellen contrast is very much like that, though it would come across stronger if Ellen were more “there” – she probably doesn’t have much more than ten minutes of screen time.

[…] (Black Gate): Growing up in Southern California in the 60’s and 70’s was a movie lover’s dream. Late […]