What Makes a Project a “Passion Project”?

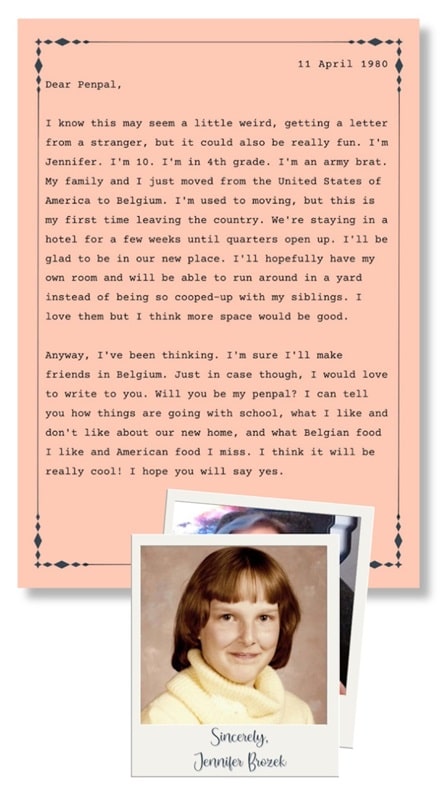

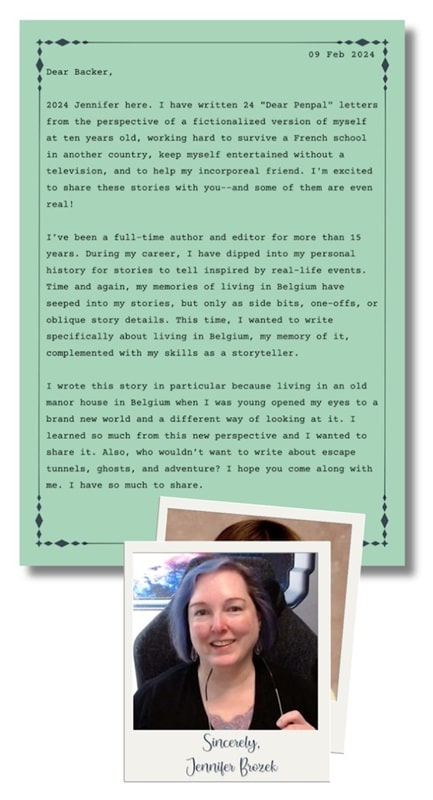

For me, a passion project is something that could not be sold in a traditional sense to the mainstream market, but you want — need — to create it anyway. Dear Penpal, Belgium 1980 is the kind of project that I could not sell to a traditional publication house despite it being a middle grade-appropriate cozy ghost story. Partly because it is told in 24 physical letters. Partly because while it is middle grade-appropriate, its ephemeral nature and subject matter will appeal to a broad range of ages — which makes it hard for any marketing department to categorize.

It’s not just a ghost story. Nor is it just a story of a Gen-X, latchkey kid trying to survive in a foreign country. Nor is it just a story about the importance of family (especially a military family) and the power of friendship. It is a project that defies conventional age, topic, and multimedia barriers.

For this passion project, the questions I get most often are: “Why physical letters?” and “Why Belgium in 1980?”

Why Letters?

I grew up in the time before there was an internet, and was an adult by the time “the internet” (with its dial-up shrieks, ping floods, and 12400 or 28800 connections) had become almost mainstream. I remember when pen pals were a thing and receiving mail was a joy. There was more to mail than bills and spam.

There were messages from afar and stories told in intermittent pieces. In these letters, conversations intertwined and rambled, answered questions morphed by the time the letter receiver read them. Nuggets of daily life intervened. It was as personal as a diary and as open as a postcard. This is an experience that I want everyone to have. To know what it is like to look forward to postal (snail) mail. Also, to encourage those that have never had a pen pal to seek one out.

Why “Belgium in 1980”?

That was in the middle of the three year period that I lived in Belgium. I arrived in 1979 and left in 1981. Living in Belgium at that young age taught me so much — for good and ill. It is a part of me and my history that I have dipped into for inspiration time and again. But it has never been the focus of a story. I wanted to honor my time there with a semi-true story about living in a 300 year old manor house in a foreign country. So much of who I am today has its roots in that time in my life. It is a personal story intertwined with a ghost story, and I really think people will enjoy it.

Don Bassingwaithe, the editor whose office I virtually stomped into (via email) in 2000 and demanded he hire me to write for Black Gate magazine, has watched my career progress since then. He’s asked me a few questions.

What, Exactly, is “Dear Penpal, Belgium 1980”?

Dear Penpal, Belgium 1980 is a unique, middle grade-appropriate ghost story told through 24 physical letters. These letters have been written by a fictionalized ten-year-old version of me, Jennifer Brozek, based on my actual life while living in a 300 year old manor house in Belgium in 1980. The project is going to be funded through Kickstarter that will be active from March 26, 2024 to April 26, 2024. Backers will receive two physical letters a month from me for a year.

How is Writing in Letters Different from Writing a more Traditional Novel?

When you write a story as a series of letters, there are several things to remember.

- First, while all of the letters can be read one after the other, that will usually be after the initial read. The story needs to hang together when read serialized, as well as a whole.

- Second, letters are personal and rambling and not perfectly written. Especially when written as if they were typed on a typewriter. This goes for letter writers of all ages. There is a sense of immediacy that is delayed. The letter writer is giving snapshot vignettes of their life to the letter readers.

- Third, it is a story. There needs to be a structure to that story, told over the series of letters. A beginning, middle, and end. The letter writer doesn’t know they are in a story. The reader does. Use that to foreshadow what is to come. At the same time, each letter needs a beginning, middle, and end. It’s a bit like writing a novella in a series of flash fiction pieces.

Without Spoilers, what do You Think will be Readers’ Favorite part of Dear Penpal? What’s Four Favorite Part?

Honestly, I’m not sure. I would like to think that the readers will love getting to know the house I lived in while I lived in Belgium — its age, quirks, and weirdness. I think some of the readers will have fun trying to figure out which parts of the story actually happened and which were made up. I’m not being shy about it being based on events in my life. Maybe it will be the novelty of receiving mail every month and anticipating it. I think there is a little bit of something in the project for everyone to love.

Me? I think my favorite part was talking with my sister and reminiscing. She remembered things I didn’t remember and I remembered things she didn’t remember. So, I guess that means the act of creation of this passion project was my favorite part. I smiled all the way through it.

Is There Anything that Stays with You from Those Three Years in Belgium? It’s been a While!

Physically? Oh yes. There’s a ceramic “grail” I made. I think that was the one thing I have personally had in my life since Belgium. I’ve also inherited things from our time in Belgium from my parents — some stuff from trips to Spain and Germany. Not a lot of things, but all of it is meaningful.

Mentally, yes. I have a great love of old architecture that keeps cropping up in my stories. I understand how much a person’s world opens up when they visit or live outside of what they grew up with. It’s one of the reasons I encourage people to get outside their comfort zones if they can. Also, I think my time there has made me less afraid of saying, “I don’t know.” In America, there seems to be a taboo against admitting that there are things you don’t know about. As an American in Belgium, being honest was a survival trait.

If you were to write a letter to yourself in 1980, what would you say?

I think I would assure myself my time in the French school would end and that I would make friends in the American school. That was a hard time in my life. I was very lonely. It is only in retrospect that I can say that I learned more than I wanted to during that six month period and it made me a better person today.

What else have you been working on?

Kind of a lot. Being a full-time publishing professional means you need to be able to work in multiple different silos to pay the bills.

As an author: This year, I have already finished one novel and two contracted short stories. I’m working on three more contracted short stories. I’ve also had a novel, Shadowrun: Auditions, published as well as several very fun interviews. I’ve started prelim work on my next Shadowrun novel. Of course, there is all the stuff in and around Dear Penpal, Belgium 1980.

As an editor: This year, I have had one anthology released, 99 Fleeting Fantasies, and am finishing up another one. There have been some fun interviews about my editing work, too. Especially the collab I did with Cat Rambo on The Reinvented Detective anthology. I’ve also taken on more editing work with Catalyst Game Labs.

As a streamer: I play in a regular D&D Eberron Infinity and Beyond game on Arvan Eleron’s twitch channel. I also got to play in The Broken Hearts Club Buffy mini-series on the Shadows of Nox channel.

Jennifer Brozek is an award winning author, editor, and tie-in writer. A Secret Guide to Fighting Elder Gods, Never Let Me Sleep, and The Last Days of Salton Academy were all finalists for the Bram Stoker Award. She was awarded the Scribe Award for best tie-in Young Adult novel, The Nellus Academy Incident, and won an Australian Shadows Award for best edited publication. Her editing work has also been nominated for the British Fantasy award and the Hugo award. Visit Jennifer’s worlds at jenniferbrozek.com.

Wow! Congratulations on completing your passion project, and thank you for sharing this insider information about it! Best wishes on getting this publishing effort up and running. I understand that this publication model can be both highly enjoyable and fairly profitable for the author, and can confirm that receiving a story serialized in letters is its own unique sort of joy since my cousin gifted me such an experience last Christmas.

Is there any likelihood of a sequel or alternate epistolary branch, if publishing goes well?

There is a always a possibility. It really depends on how well the KS does and if there is an audience. If so…yes. I do know what the next one is. 😀

~Jennifer

[…] What Makes a Project a “Passion Project”? In this interview with Black Gate Magazine, I answer “Why letters?” and “Why […]