The Harp and The Blade: A Bard’s Adventures in Old France

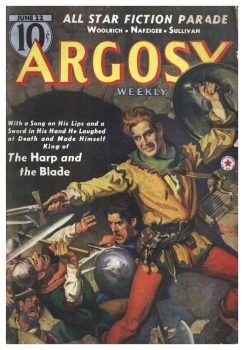

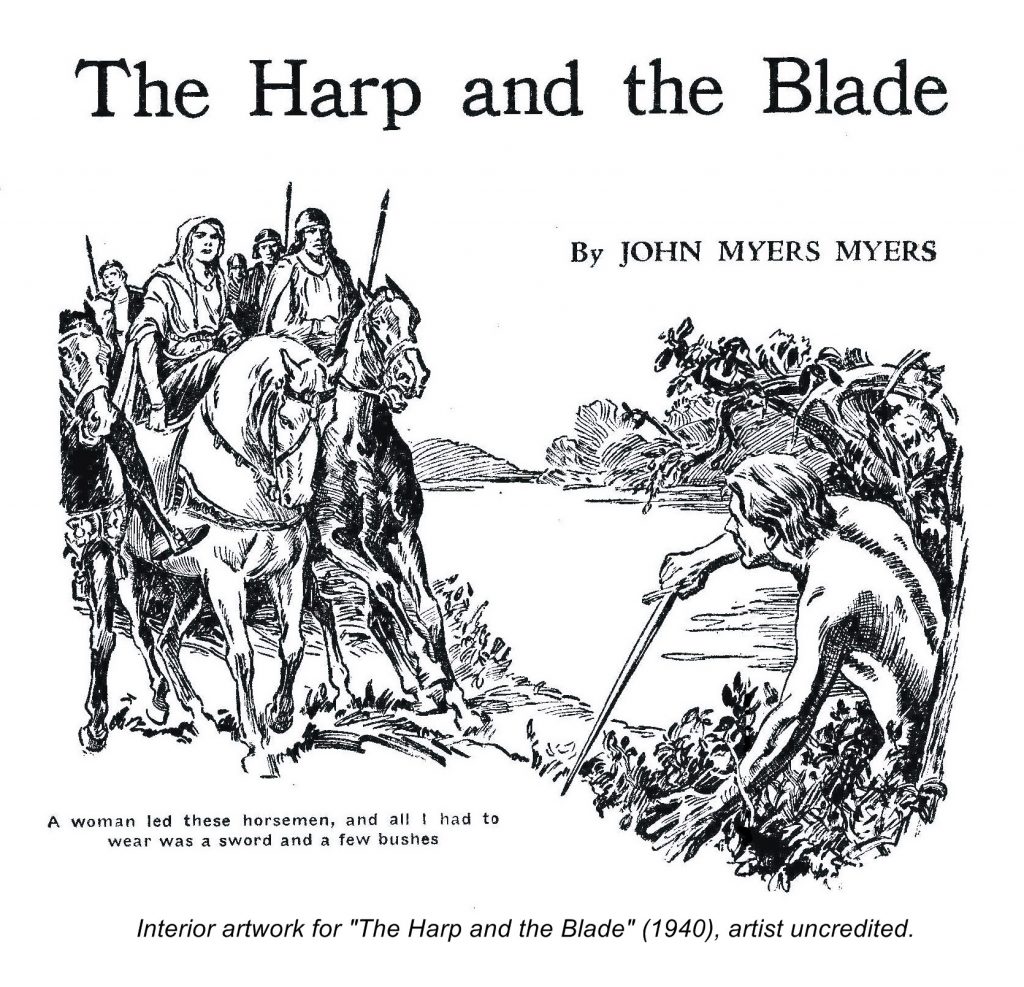

The first printing of John Meyers Meyers’ The Harp and the Blade was serialized in seven parts in the pulp magazine Argosy from June through early August of 1940. Although the Rudolph Belarski painting on the cover of the June 22 issue might suggest that The Harp and the Blade is a fantasy, it is not. It is instead a straight adventure story set in medieval France.

The first printing of John Meyers Meyers’ The Harp and the Blade was serialized in seven parts in the pulp magazine Argosy from June through early August of 1940. Although the Rudolph Belarski painting on the cover of the June 22 issue might suggest that The Harp and the Blade is a fantasy, it is not. It is instead a straight adventure story set in medieval France.

What makes this story really interesting is its feeling of reality and the aliveness of the characters. We do not observe the story as if a Hollywood piece, at a comfortable distance from the action. Nor do we wallow in the filth, fleas, and mud. We are shown the reality of battle, the value of a laugh with friends, the necessity of a drink, and the delight of a kiss from one’s wife. The characters’ values are also of paramount importance, with clear demarcations made between good and bad. When there is a case of muddy morals, there is also a rationale, which may not be to our liking, but which makes sense for the characters involved.

The question is never asked — what makes life worth living? Instead, we are shown the answer in the simple things that the hero wants and that his blood-brother already has. This is a man’s tale, not grandiose, but heartfelt and homey as brown bread and good ale.

It has been said that Meyers’ female characters are weak, merely background ornaments. But this is not so. While the two female characters in this story don’t have much to do while on stage, they are nonetheless, important. It is more that their values, to which they are consistent, do not jibe well with our current moral views. The women do not fight as Amazons, nor do they seek a position in society out-of-keeping with medieval roles. Within their gender-specific roles they are shown great respect and honor. They are valued, and if this occasionally strikes us as the value of ownership by a man, Meyers also makes it clear that the women are strong and willing and able to take fate into their own hands.

Meyers’ writing style is straightforward, which suits the tale. His descriptions are lively and colorful and his sense of humor, wonderful. Now that we have that overview let’s get into the specifics. Be warned, spoilers ahead.

Meyers’ writing style is straightforward, which suits the tale. His descriptions are lively and colorful and his sense of humor, wonderful. Now that we have that overview let’s get into the specifics. Be warned, spoilers ahead.

Finnian is an itinerant Irish bard in 9th century France. Charlemagne has recently died and the empire is crumbling to bits. Petty warlords are rising and bandits are everywhere. Leaders who treat men as men and not animals are hard to come by. Many monasteries have been burned to the ground and the remaining ones are fortified with military-minded abbots. Many of the monks do not have the calling but are simply men seeking refuge. It is a dangerous time.

Finnian tries to stay out of local affairs but is put under a geas by an aged Pictish priest. “While you are in my land,” the old man says, “you will aid any man or woman in need.” Is this a real magic spell? That is never made perfectly clear, and we wonder. Regardless, Finnian immediately becomes involved in the turbulent affairs of the region.

The story unfolds from here like a scroll. He becomes blood-brother to the best and most humane of the local leaders — Conan, the Breton. He saves a Frankish girl from being sold as a slave by Danish Vikings. He leads a group of rescuers to save Conan after he’s kidnapped by another warlord. Later, he and Conan team up to rid the area of a large band of pretty awful bandits. Finnian also helps Conan make alliances with two monasteries. The bard begins to dream of a life as one of Conan’s chieftains with a hall and family of his own.

The story unfolds from here like a scroll. He becomes blood-brother to the best and most humane of the local leaders — Conan, the Breton. He saves a Frankish girl from being sold as a slave by Danish Vikings. He leads a group of rescuers to save Conan after he’s kidnapped by another warlord. Later, he and Conan team up to rid the area of a large band of pretty awful bandits. Finnian also helps Conan make alliances with two monasteries. The bard begins to dream of a life as one of Conan’s chieftains with a hall and family of his own.

Finnian’s interactions with Conan are as interesting as his interactions with the monks and abbots, but for different reasons. Finnian and Conan are both young men with heavy responsibilities. Their goals are initially different but become more aligned as the story progresses.

As a bard, Finnian is a learned man. He’s educated and can compose songs and poems. On his travels he often seeks refuge in monasteries where he can meet with other learned men and trade news and song. Sometimes, he can be useful to the monks in other ways. One of my favorite scenes in the book deals with Finnian and a group of obnoxious monks he’s been asked to tutor in reading Latin. They’ve been used to a sweet old monk as a teacher but Finnian takes a more marital approach to get through to them. Here is how he handles it.

The next day I marched before the students and laid my sheathed sword on the desk. ‘Father Michael has asked me to help you to read,’ I announced, gazing from one to another with a challenge they instantly recognized and resented. ‘I expect your attention…. Fathers of the Church are supposed to have two things you midges lack,’ I said belligerently. ‘They are grammar and courtesy, and I propose to teach you both.’ I fixed my eyes on a young man who looked more intelligent as well as more insolent than the rest. ‘Can you decline mensa?’

He smirked. ‘No, but I can decline to answer.’

I rose when his mates had finished laughing. ’This,’ I stated, picking up my sword for him to see, ‘is a thing. It’s name is a noun, which can be declined but not conjugated.’

He pursed his lips mockingly. ‘Oh?’

‘The act of moving a thing,’ I pursued, ‘is a verb, which can be conjugated but not declined.’ I hit him over the head with the sheathed blade, and he sagged in his seat, almost out. ‘To confuse one with the other,’ I concluded as I resumed my seat, ‘is a shocking fundamental mistake.’

After a few more such incidents, interest in literacy waxed. All were attentive, and the better minds began to take hold. Not that I could claim to be popular with my class….

This is not the kind of scene you’re likely to see in a contemporary story. I don’t say this solely as a reflection of Meyers’ writing, it brings up a point about good pulp writing. You must be able to relate to the characters. Now me, I’ve been both a teacher of punk students and someone who enjoys their Latin. So I related to this scene very strongly, finding it hysterical. Taking it further, can we generally relate to Finnian, the Bard and Conan, the Breton? Do we still know young men such as these? I’m not sure we do but even if we don’t, we still want to. There’s something about them that makes us feel good, trusting that we can leave important tasks in their capable hands.

As mentioned previously, at first blush this story seems like a stock fantasy — an Irish Bard has a mysterious encounter with a wizard and is cursed to set things right in the kingdom beset by Viking raiders, bandits, and evil warlords. But if you look closer, you’ll notice some differences that make the story straight adventure and not fantasy. The geas might, or might not, be magic. It might just be coincidence and bad luck that starts Finnian on his round of heroic deeds. He doesn’t resent his fate, instead he rushes to meet it. His bravery is rewarded not by treasure but with friendship. Eventually, he begins to have dreams of home and hearth which is not at all what he wanted in the beginning. But Finnian doesn’t need to be a 9th century Bard to make the story work. Nor does Conan need to be local lord. What makes this story an adventure is that you can transpose the details anywhere and anywhen. A fantasy story isn’t like that, the setting is an important part of the tale.

Do I recommend The Harp and the Blade? Absolutely… if you remember that it’s a man’s adventure story and not a mythical tale. Equally, it’s not woke. I shouldn’t need to apologize for that but these are the times. Actually, there’s little here for political correctness to object to, except perhaps for the handling of the female characters and the liberal amount of drinking displayed.

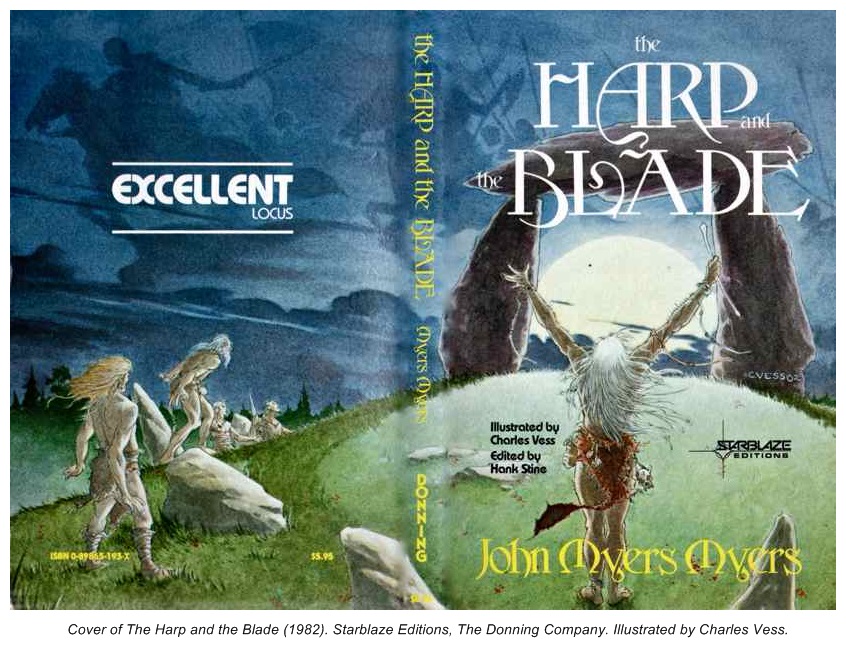

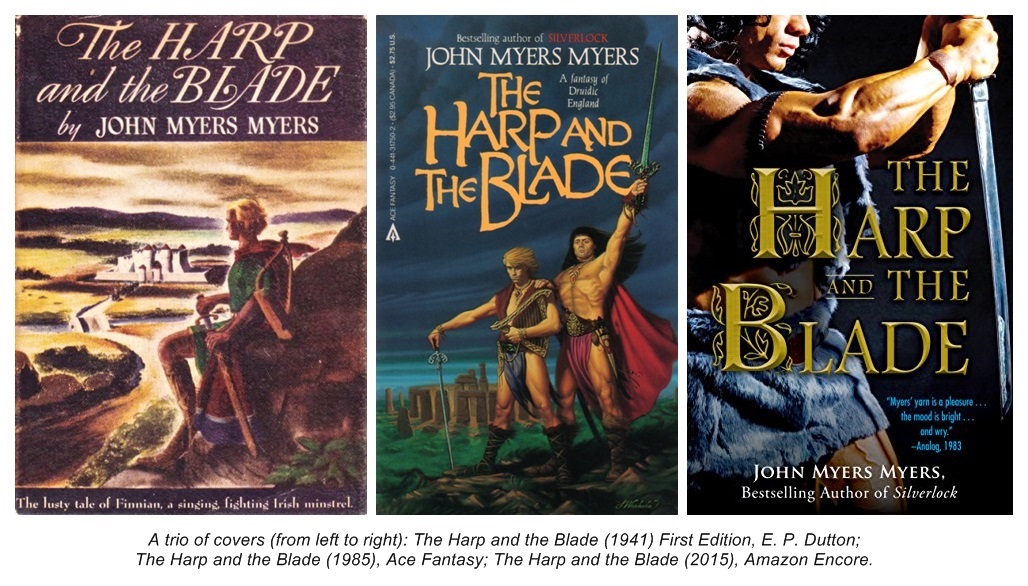

Meyers does a fine job with his unpretentious tale and you will be carried along. ARGOSY wouldn’t have published it if it wasn’t good. After all, in that same period their stable of adventure writers included — Johnston McCulley, C. S. Forester, Theodore Roscoe, Cornell Woolrich and Max Brand, to name a few. If you’d like to read the story it’s still possible to find copies of Argosy in digital form online. But it’s far easier to get a digital or print copy of The Harp and the Blade on Amazon, eBay, or in various online book shops. Happy reading!

If you’d like to read the story it’s still possible to find copies of Argosy in digital form online. But it’s far easier to get a digital or print copy of The Harp and the Blade on Amazon, eBay, or in various online book shops. Happy reading!

SARA LIGHT-WALLER is a writer, illustrator, and avid pulp and vintage science fiction & fantasy fan. In 2020, she won the prestigious Cosmos Award for her illustrated space opera story — “Battle at Neptune.” She’s published two illustrated new pulp books — Landscape of Darkness and Anchor: A Strange Tale of Time and is a regular contributor to several pulp blogs. Catch up with her at Lucina Press.

The Harp and the Blade fooled me enough to read it, expecting a bit more of the fantasy genre element, but I am glad to have been fooled into reading it. A nice piece of historical fiction that does not read like “ye olde booke”.

It was definitely marketed as a Fantasy story. Of course, that was all smoke and mirrors, as were the depictions of Conan the barbarian on the more recent covers. Tsk. Marketing Departments! I’m glad you liked the story. I was kind of expecting “ye olde booke” when I read it, too. LOL I’m glad it proved a much better tale.

Sounds like a great novel!

[…] a new article in the online magazine, Black Gate: Adventures in Fantasy Literature. Ironically, the book I’m reviewing is not a fantasy story, even though it was marketed as […]

Amazon also shows a copy of this as a “Sunday Newspaper Novel,” with an accompanying picture, and there appears to be one copy available.