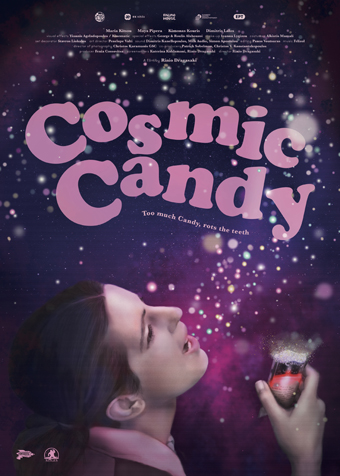

Fantasia 2020, Part XX: Cosmic Candy

There is, or was, or might have been according to some, a movement in Greek cinema that started and flourished in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century called the Greek Weird Wave. This movement, if it existed — and Lanthimos himself is skeptical, while others say it’s a thing of the past — was perceived to be anchored by the films of Yorgos Lanthimos and Athina Rachel Tsangari, and characterised by surreal plot situations, precise cinematography and alienated, emotionally muted characters. (It’s quite far from prose weird fiction or even the New Weird, often lacking any element of the fantastic.) Were the Weird Wave is a thing to have ever existed, it would be very tempting to place Rinio Dragasaki’s debut feature Cosmic Candy within it.

There is, or was, or might have been according to some, a movement in Greek cinema that started and flourished in the first half of the second decade of the twenty-first century called the Greek Weird Wave. This movement, if it existed — and Lanthimos himself is skeptical, while others say it’s a thing of the past — was perceived to be anchored by the films of Yorgos Lanthimos and Athina Rachel Tsangari, and characterised by surreal plot situations, precise cinematography and alienated, emotionally muted characters. (It’s quite far from prose weird fiction or even the New Weird, often lacking any element of the fantastic.) Were the Weird Wave is a thing to have ever existed, it would be very tempting to place Rinio Dragasaki’s debut feature Cosmic Candy within it.

Written by Dragasaki with Katerina Kaklamani, it follows Anna (Maria Kitsou), a youngish woman who works at a convenience store and is addicted to Cosmic Candy, a sugary substance the store’s decided to no longer carry. Anna suffers from OCD and, apparently, at least mild depression, ordering fitness equpiment online that she never opens. Then she comes home one evening to find a young girl, her neighbour Persa (Pipera Maya), hanging around her front door. Persa’s father has vanished, and despite herself Anna takes in the extroverted high-energy Persa. Anna’s own father, we learn, vanished some time ago, and the main part of the film is the bonding between Anna and Persa as Anna investigates Persa’s life. She tries to understand what’s happened to Persa’s father and where the girl can live long-term, while at the same time trying not to get fired from her job, and helping Persa prepare for her school pageant.

You can see the outline of some very familiar story structures in the foregoing, and one of the interesting aspects of Cosmic Candy is the way it uses those structures while also occasionally pushing back against them. There is overall a straightforwardness to the film, but it’s pulled into some unusual shapes by Anna’s mental and emotional states, and a mounting tendency to the surreal. Some elements of it struck me as possibly referring to cultural knowledge I did not have (specifically the significance Persa’s school play, in which she plays a figure from the 19th-century struggle for Greek Independence). But the story’s always clear, and told with a distinctive gentleness, a sympathy for all its characters. As it goes on it becomes more surreal, anchored always by subtly powerful cinematography and the alienated Anna’s muted emotional reaction: thus, perhaps, part of the Weird Wave, if such a thing exists.

Technically Cosmic Candy can be said to be a genre story in that there’s a mystery, and a tale of crime seen edge-on. Mostly, though, it’s a story of a mismatched couple coming to bond and shape each other’s world. As such it’s perfectly solid; you see why the two characters are drawn to each other despite their basic differences in temperament, and the adventures and exploits they pull each other into are well-planned and build well — if it’s clear that Persa’s play will always be the climax of the film, an extended road trip the two of them take in search of another of her family members nicely diverts the tale for just long enough, giving us a less expected dimension.

What is perhaps most distinctive about the movie are some moments of vision Anna has, in which, clad in her job’s uniform, she drifts through convenience-store aisles under a bright starscape. The colour here is bright, unlike the textured lighting of the film’s everyday reality, conveying a sense of an altered state of consciousness. It pays off late in the film with a rejection of a long-sought transcendence, and the implication that life means involvement with the situations of this world.

What is perhaps most distinctive about the movie are some moments of vision Anna has, in which, clad in her job’s uniform, she drifts through convenience-store aisles under a bright starscape. The colour here is bright, unlike the textured lighting of the film’s everyday reality, conveying a sense of an altered state of consciousness. It pays off late in the film with a rejection of a long-sought transcendence, and the implication that life means involvement with the situations of this world.

I am not convinced by the film’s dramatisation of this argument, though, and for two reasons. First, there’s no sense of balance between the candyland visions and the mundane world — the visions are few and brief, and there’s not much of a sense of them shaping Anna. The everyday world’s the focus of the film from the start, so the rejection of what’s beyond it does not land dramatically. There’s no doubt about what’s going to happen. (Especially unfortunate as the world rejected seems in its brief appearance to be much more interesting than the world of consensus reality.)

Second, the everyday world to which Anna turns is not really credible as an everyday world. As I noted above, it’s shaped by very familiar plot structures. It feels like the world of a Hollywood film — a good one, maybe, but something essentially bound by genre presumptions. Persa’s too much the precious kid of any number of wacky comedies. It’s all solid enough in its own right, but it’s difficult to accept this as a movie that can make a credible statement about reality.

Second, the everyday world to which Anna turns is not really credible as an everyday world. As I noted above, it’s shaped by very familiar plot structures. It feels like the world of a Hollywood film — a good one, maybe, but something essentially bound by genre presumptions. Persa’s too much the precious kid of any number of wacky comedies. It’s all solid enough in its own right, but it’s difficult to accept this as a movie that can make a credible statement about reality.

I can see an argument that part of the genres it’s referring to might include a kind of nose-to-the-grindstone theme to show how the bond of the characters has grown over the course of the film, so that theme here is meant as an ironic quotation. If so, it doesn’t work because of the first point I mentioned. All the mismatched-duo movies we’ve all seen, and the choices those characters always make, set us up to know what’s going to happen here. There’s no surprise at a crucial part of the film, and though the movie recovers itself nicely to provide a strong ending, I still come away feeling that something slipped away from Cosmic Candy. It’s a fine movie, but there was material here I thought could have been better developed, into something even stronger.

There is a sense, maybe, in which this film was caught between being too weird and not being weird enough. More of the cosmic strangeness might have helped. None of it, and I doubt it would have been missed. There’s just enough here to hint at something better, but had it never been there at all, this still would have seemed a weird movie due to Anna’s nature and her choices. As it is, it’s still very solid. I personally cant help but wish it had its emphasis in different places.

There is a sense, maybe, in which this film was caught between being too weird and not being weird enough. More of the cosmic strangeness might have helped. None of it, and I doubt it would have been missed. There’s just enough here to hint at something better, but had it never been there at all, this still would have seemed a weird movie due to Anna’s nature and her choices. As it is, it’s still very solid. I personally cant help but wish it had its emphasis in different places.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.