Alien Languages and Scientific Mysteries: The Best of Hal Clement

|

|

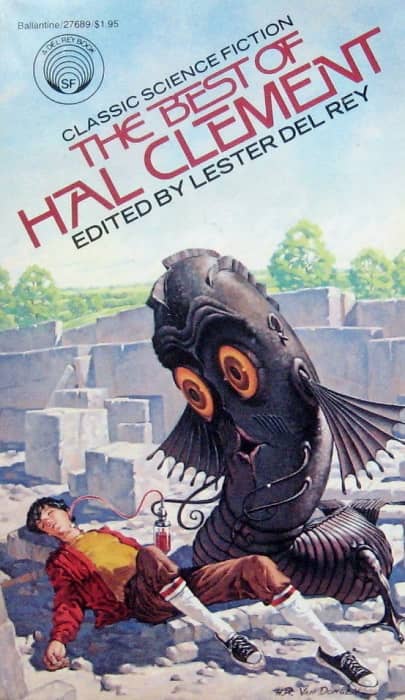

The Best of Hal Clement (Del Rey, 1979). Cover by H. R. Van Dongen

The Best of Hal Clement (1979) was, according to my research, the nineteenth installment in Lester Del Rey’s Classic Science Fiction Series. (Only two more to go!) Lester Del Rey (1915–1993) provided the introduction (his fifth and final in the series). Hal Clement, whose real name was Henry Clement Stubbs (1922–2003), was still living at the time and thus available to do the Afterward. Sci-fi artist H. R. Van Dongen (1920–2010) provides his eighth cover in the series. His work graced more volumes than any other artist in the series.

The first time I heard of Hal Clement was in a Black Gate post by John O’Neill back in 2013 about this very book. As usual, John gave a fine review. But I commented back then (you can still see my response in the original post):

This review in no way enticed me to seek out or try reading any Hal Clement. I don’t think it was a bad review, Clement just doesn’t sound very compelling to me.

Why this reaction? In that post John O’Neill accurately summed up Clement’s writing:

Clement wrote in a category that is nearly extinct today: true hard science fiction, in which The Problem — the scientific mystery or engineering puzzle at the heart of the tale — is the central character, and the flesh-and-blood characters that inhabit the story are there chiefly to solve The Problem. When Clement talked about writing, he mostly talked about the requirement to keep his stories as scientifically accurate as possible; he described the essential role of science fiction readers as “finding as many as possible of the author’s statements or implications which conflict with the facts as science currently understands them.”

John further commented, “Okay, that ain’t how I view my role as a reader — and I read a fair amount of hard SF. But your mileage may vary.”

So, to say the least, I was not looking forward to reviewing The Best of Hal Clement. “Hard” science fiction does not sound like my cup of tea. Nevertheless, to my surprise, I really enjoyed this book.

[Click the images for science-sized versions.]

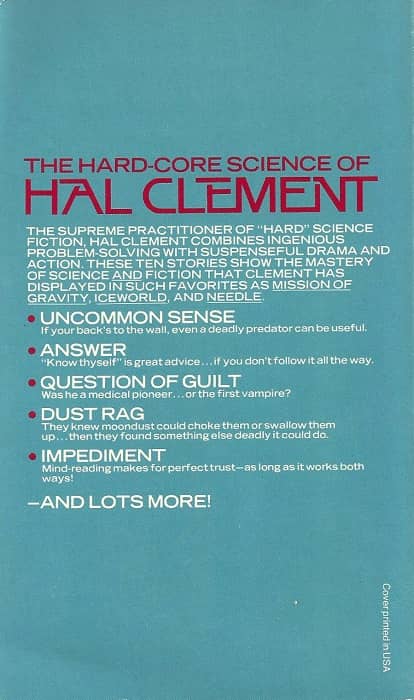

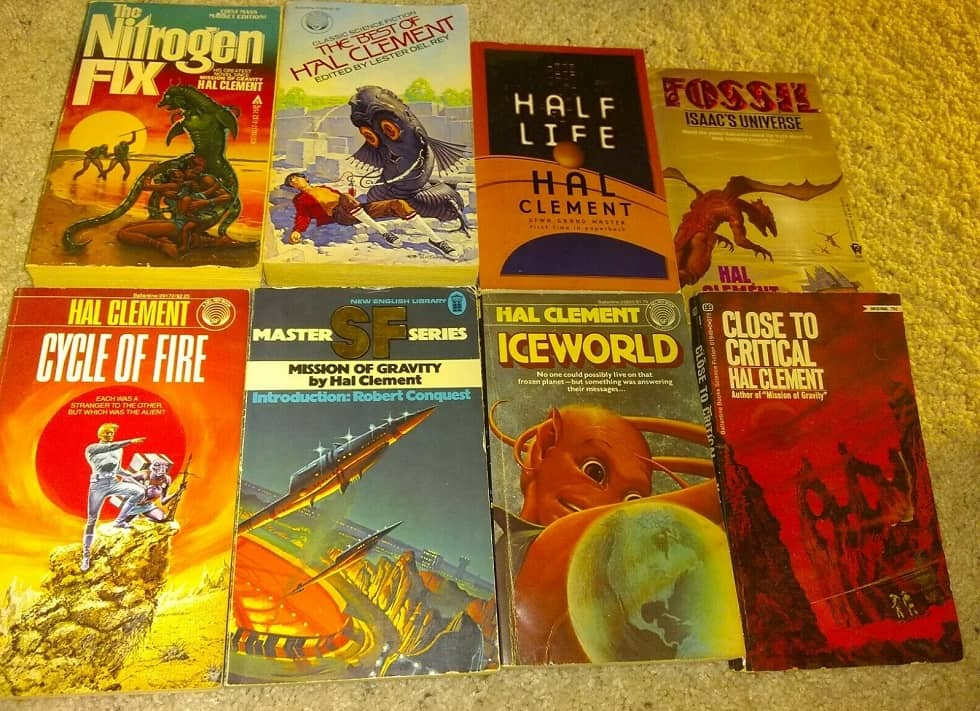

The paperback Hal Clement

First off, I think John O’Neill’s criticism of Clement is largely correct. I think Clement often seemed far more concerned with scientific details than he was with the story at hand. And many of the scientific details he includes within his tales I found, on the whole, to be mind-numbingly boring (though sometimes occasionally interesting). A small sample:

The attempts at explanation, however, seemed to be futile as the first words had been. [The alien’s] premonition of the futility of drawings and diagrams was amply justified; not only were the conventions used in drawing by the engineers of his people utterly different from those of Earth, but it is far from certain that the atoms and molecules the aliens tried to draw were the same objects that a terrestrial chemist would have envisioned. It must be remembered that the “atoms” of physics and of chemistry, used by members of the same race, differ to an embarrassing extent (“Impediment” p. 28).

Snore. ZZZZZZZ. Snore. ZZZZZZZ.

That being said, I often found myself engrossed with the “problem” the characters were dealing with, because it seemed to hint at where the story was going. Though the scientific details (or speculations) could seem superfluous (or just word-salad), they sometimes offered narrative bread crumbs, suggesting further possibilities. Thus the so-called “problem” often slowly made it intriguing.

For example, in “Impediment” an alien and human try to communicate, with neither knowing the other’s language or anything about the other species. In “Unjustified Assumption” an alien makes a mistake that is almost drastic due to a poor assumption, but which one? And in “Dust Rag” astronauts on the moon try to figure out how to remove magnetic dust from their visors, in order to make it back to the safety of the base. These stories, and others in The Best of Hal Clement, are something of scientific mysteries that you want to see solved by the characters.

Don’t misunderstand me. When you finish just about any of Clement’s stories, you feel you’ve experienced more of a science lesson than good story-telling. But surprisingly, I discovered an attraction to Clement’s scientific curiosity and coherence. It was clearly a form of writing that took much time and effort.

I note that of all the Del Rey Best ofs, The Best of Hal Clement has the fewest stories. Why? Obviously it took a lot of time to fill out the scientific details and think through the possible outcomes in Clement’s stories. Since he seemed unwilling to fudge the details, he developed the skills to slowly, meticulously and plausibly built up these ideas.

More vintage Hal Clement

I think Clement believed that his readers were following the details of such scientific puzzles as well. His characters often have “a-ha” moments when they finally figure something out and Clement often expresses or implies the reader was already ahead of them. But, to be fully honest, I rarely saw the obviousness of any given answer. Here’s an example:

Really, I don’t know why it didn’t occur to us sooner. The trouble is, the ‘circuit’ having the characteristics demanded by this set of data — a problem-solving circuit, in other words — is identical with the electronic setup in one of the tubes of this machine. Obviously! After all, that’s what the machine’s for, and whether the human brain really works this way or not, it’s certainly a possible solution (“Answer” p. 164).

Though I might not be the sharpest scientific tool in the shed, as a logician I fare a bit better. And in this regard, I appreciated Clement even more. I tend to read more horror and fantasy. I like sci-fi but one of the things that turns me off is the sort of naïve optimism that portrays Science (with a capital “S”) as having the ability to solve every problem we might come up against — the “I’m going to have to science the $%#! out of this” attitude. Clement’s stories sometimes end pessimistically because he does not seem to believe that. In one of his stories, he has a character say what I’m sure is Clement’s own view of science:

“Don’t tell me you’re one of those fellows who thinks there’s an answer to every problem.”

“I am. It may not be the answer we want, but there is one.” (“Dust Rag” p. 88).

I found Clement to be a delightful writer. Though his “hard” sci-fi approach could be a bit didactic at times, his characterization really develops throughout the stories. One of the more moving tales was “A Question of Guilt,” in which a Roman-era “doctor” seeks to help his anemic son. Using his current scientific knowledge, the doctor works through possible ways he can cure his son’s ailment. For the reader, the tragedy plays out heartbreakingly as you know there is no known medical cure in Ancient Times, nor was there technology advanced enough to develop one. Quite sad.

So, I was surprised. It seems that my “mileage varied” John O’Neill! I think The Best of Hal Clement should still be read and appreciated. Hard sci-fi, even Clement’s kind, still has its charms.

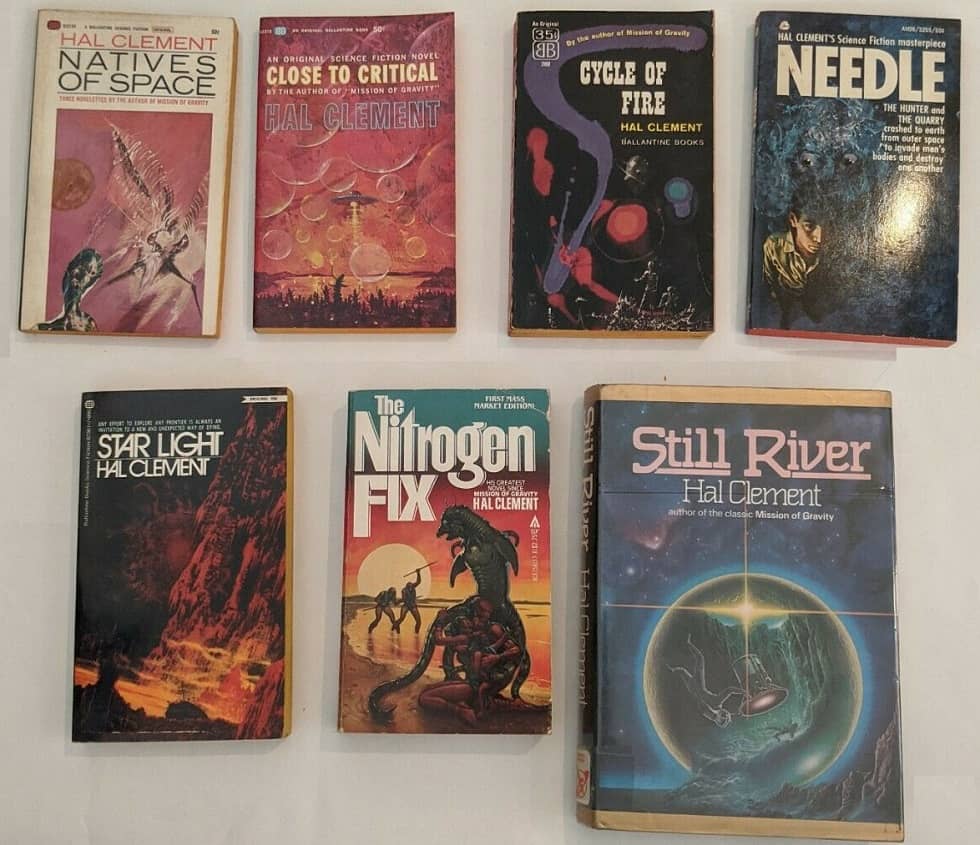

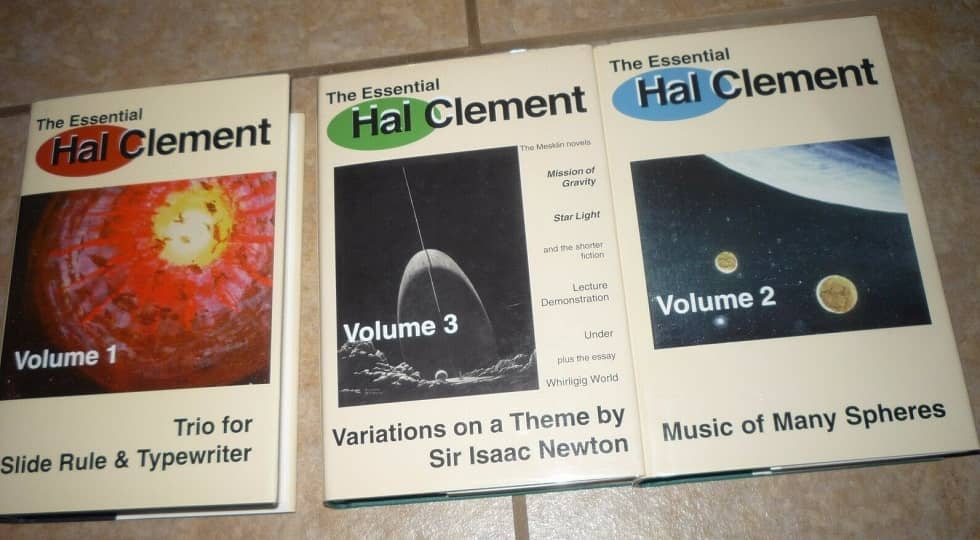

The Essential Hal Clement (three volumes, from NESFA Press, 1998-2000]

Here’s the complete Table of Contents for The Best of Hal Clement:

Hal Clement: Rationalist, by Lester Del Rey

“Impediment” (Astounding Science-Fiction, 1942)

“Technical Error” (Astounding Science-Fiction, 1943)

“Uncommon Sense” (Astounding Science-Fiction, 1945)

“Assumption Unjustified” (Astounding Science-Fiction, 1946)

“Answer” (Astounding Science-Fiction, 1947)

“Dust Rag” (Astounding Science Fiction, 1956)

“Bulge” (Worlds of If, 1958)

“Mistaken for Granted” (Worlds of If, 1974)

“Question of Guilt” (The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series IV, 1976)

“Stuck with It” (Stellar #2, 1976)

Afterword, by Hal Clement

The Best of Hal Clement was published in June 1979 by Del Rey Books. It is 396 pages in paperback, originally priced at $1.95. The cover is by H. R. Van Dongen. It is out of print. Gateway / Orion released a digital edition in 2013.

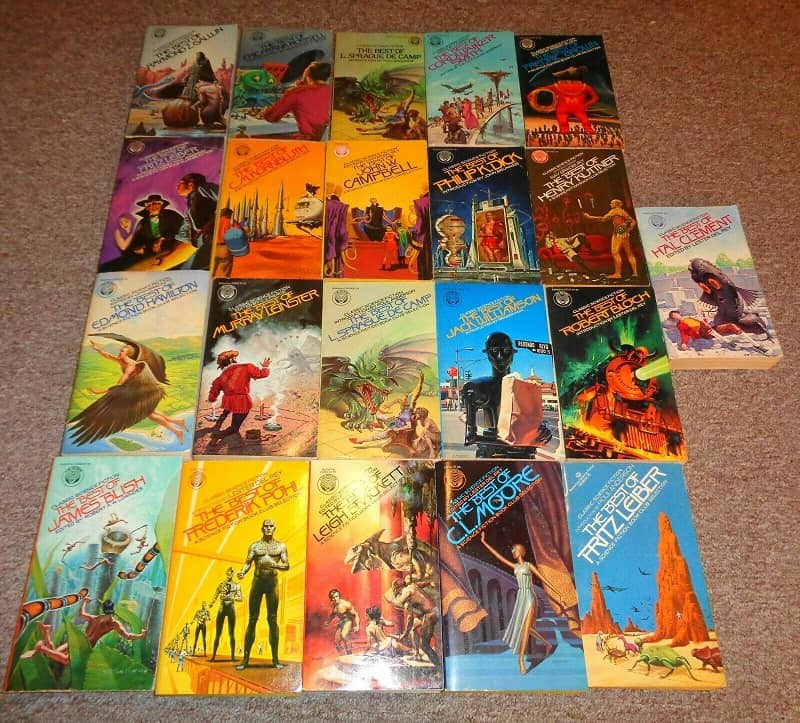

20 volumes of the Ballantine Classics of Science Fiction (missing Weinbaum, Del Rey, and Brunner)

Our previous coverage of the Classics of Science Fiction line includes (in order of publication):

- The Best of Stanley Weinbaum by James McGlothlin (1974)

- The Best of Henry Kuttner by James McGlothlin (1975)

- The Best of Cordwainer Smith by James McGlothlin (1975)

- The Best of C. L. Moore by James McGlothlin (1976)

- The Best of Frederik Pohl by James McGlothlin (1976)

- The Best of John W. Campbell by James McGlothlin (1976)

- The Best of C. M. Kornbluth by James McGlothlin (1977)

- The Best of Philip K. Dick by James McGlothlin (1977)

- The Best of Fredric Brown by James McGlothlin (1977)

- The Best of Edmond Hamilton by Ryan Harvey (1977)

- The Best of Leigh Brackett by Ryan Harvey (1977)

- The Best of Robert Bloch by James McGlothlin (1977)

- The Best of Murray Leinster by James McGlothlin (1978)

- The Best of L. Sprague De Camp, by James McGlothlin (1978)

- The Best of Jack Williamson by James McGlothin (1978)

- The Best of Raymond Z. Gallun by James McGlothlin (1978)

- The Best of Lester del Rey by Jason McGregor (1978)

- The Best of Eric Frank Russell by James McGlothlin (1978)

- The Best of Hal Clement by James McGlothin (1979)

- The Best of James Blish by John O’Neill (1979)

- The Best of Fritz Leiber by James McGlothlin (1979)

- The Best of John Brunner by John O’Neill (1988)

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

If someone loves his subject and is totally invested in it, he can make it engaging, even if it’s dryasdust nuts n’ bolts. That’s Clement. It’s the same sort of thing with Arthur C. Clarke – I know his characters are flat and the dialogue is wooden. The “problem” is in the driver’s seat and I’m happy to let it take me where it will.

I’ve read only one Hal Clement novel (Half-Life) and to be honest it was terrible. Would not have finished it if I hadn’t promised to review it for the SF Site. Fascinating premise, flat story and characters.

I’ve always eyed The Best of Hal Clement as an opportunity to give the author one more chance, with smaller stakes. Short stories require much less commitment than a novel. I’m very encouraged to hear how much you enjoyed it, James!

You’ve never read Mission of Gravity, John?! Turn in your Commando Cody secret decoder ring immediately.

Not two days ago I was eyeing this book on my shelf and thinking, “It would be great to see this reviewed on Black Gate sometime.” Voila!

I’ve not read anything by Clement in many moons and he’s a long way from being my favorite author — for reasons alluded to in James’ post above — but I have a soft spot for him.

Precisely because his work exemplifies a certain style of SF which was more common decades ago, it provides good fodder for discussion of how the genre has evolved, etc. His type of storytelling was pathbreaking in its time.

John, at least two of Clement’s other novels are much more enjoyable: Mission of Gravity (already mentioned) and Close to Critical. It’s been a long time since I read either, but I clearly recall liking them both. If nothing else, his aliens are really good.

Thomas is right, John. Read MISSION OF GRAVITY, soonest. James: I first read Clement in Astounding in the early 1960s, when much of SF was “hard”, and loved his work. Your tastes may have been greatly influenced by the move to softer SF novels and stories in later decades.

R.K.: Honestly, I’ve never actually read all that much sci-fi in my life. I’ve been more a fantasy and horror guy. The only sci-fi that I can remember that really sticks out is Herbert’s Dune books, though I became more attracted, much later, to Philip K. Dick and William Gibson. I’ve actually read more sci-fi in the past few years in reading these Del Rey books. Some of them I really like such as Stanley Weinbaum and Kornbluth. Some have been a real struggle to get through, such as Cordwainer Smith, Eric Frank Russell, and Gallun (oh geesh, don’t get me started).

No doubt Clement and his style of writing was part of an acquired taste at the time. I can relate to and appreciate that. When I hear newcomers to H. P. Lovecraft complain of his purple prose and no significant female characters, etc. I get what they find annoying in him. But when you’re used to reading “weird” literature from Lovecraft’s time period, you can then so appreciate Lovecraft’s writing. I recognize Clement (and other hard sci-fi) in that same vein.