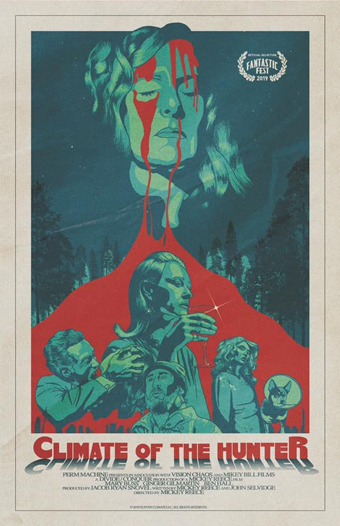

Fantasia 2020, Part X: Climate of the Hunter

Mickey Reece is a musician turned underground filmmaker with over two dozen features to his credit. In 2019 he came out with Climate of the Hunter, which he directed and wrote with John Selvidge. It streamed on-demand at this year’s Fantasia Festival, and it’s billed as a cross between old-fashioned movie melodramas in the style of Douglas Sirk — what is sometimes called a “woman’s film” — and 70s vampire movies. That’s an intriguing blend of genres. But I didn’t think the result did justice to either.

Mickey Reece is a musician turned underground filmmaker with over two dozen features to his credit. In 2019 he came out with Climate of the Hunter, which he directed and wrote with John Selvidge. It streamed on-demand at this year’s Fantasia Festival, and it’s billed as a cross between old-fashioned movie melodramas in the style of Douglas Sirk — what is sometimes called a “woman’s film” — and 70s vampire movies. That’s an intriguing blend of genres. But I didn’t think the result did justice to either.

Climate of the Hunter starts with the glimpse of a psychiatric case file dated 1977, after which we see the subject of the file: Alma (Ginger Gilmartin), a sculptor in late middle age. She and her lawyer sister Elizabeth (Mary Buss), both single, are waiting for their childhood friend Wesley (Ben Hall) to join them at the cottage where Alma’s now living. Wesley turns out to be a well-travelled Goethe-quoting man of the world, and over the course of several dinners together a romantic tension develops among the three of them, which grows worse as first Wesley’s son (Sheridan McMichael) and then Elizabeth’s daughter (Danielle Evon Ploeger) arrive. Alma, meanwhile, has begun to harbour dark suspicions about Wesley — who she comes to believe is one of the undead.

This is a solid enough structure, but the execution doesn’t work. There’s a lack of tension to both the development of the romance and the mystery of Wesley’s nature. The tone is one of uncommitted irony, flatness without humour. It’s not just that there’s no sense of building horror, there’s no involvement in the characters.

That’s partly because those characters seem to belong in different movies. Elizabeth and to an extent Wesley have the earnestness of melodrama, but the disaffected Alma has no particular narrative chemistry with either. She spends much of her time smoking pot with her rustic neighbour (Jacob Snovel), who rejoices in the name BJ Beavers and acts like it. That sounds like a jarring tonal clash with a story about a creature of the night, and so it is. The actors individually give fine performances, but collectively don’t mesh. The tone is inconsistent, each one nailing a slightly different register of irony.

The plot’s simple enough, but nevertheless manages to be unlikely. Alma’s family worries about her mental health because she chooses to live in a fairly large cottage in the woods instead of a condo in the city. Elizabeth’s daughter throws herself at Wesley for reasons that, to be polite, remain unclear. The question of Wesley’s nature is apparently resolved, then the movie proceeds as if it weren’t.

Visually, the movie’s interesting. Although clearly shot on a relatively low budget, 1970s-vintage lenses on the camera produce a distinctive period look; a certain cruciform twinkle to glints of light recalls a past era. The aspect ratio’s 4:3, further making it feel like a TV soap opera. And there’s a nice use of deep dark shadows, sometimes obscuring even the actors’ faces. Add to that a few interesting formal touches — for example, the way a voice-over names every part of a meal as it’s served, while the dish is photographed at its most luscious. There are ideas here, and some craftsmanship. But it doesn’t come out to much.

Alma as a character is underdeveloped and underserved. The fact she’s a sculptor is mentioned a couple times in dialogue, but it’s difficult to believe; she never thinks or reacts in any way that furthers that part of her identity. The movie’s more interested in her mental state, and how her sister in particular worries about her psychological health. Are her worries about Wesley dismissed, by other characters and perhaps the audience, because of her history of mental troubles?

Alma as a character is underdeveloped and underserved. The fact she’s a sculptor is mentioned a couple times in dialogue, but it’s difficult to believe; she never thinks or reacts in any way that furthers that part of her identity. The movie’s more interested in her mental state, and how her sister in particular worries about her psychological health. Are her worries about Wesley dismissed, by other characters and perhaps the audience, because of her history of mental troubles?

I suppose that could be viewed as a concern with how women’s opinions generally are dismissed or undervalued, but it’s difficult to take seriously the feminist credentials of a movie that chooses to have its lone young attractive actress be the only character to appear unclothed. More generally, Climate of the Hunter does a bad job of dramatising Alma’s interior state. She seems less delusional than apathetic. We do not see what the other characters see, and do not understand their frustration with her.

Generally, in fact, the way they speak and react to her is anachronistic. The characters have a freedom and ease in speaking about mental illness that didn’t exist more than 40 years ago. Beyond that, while there are a couple of anachronistic words or phrases — “cougar” in the slang sense, or “self-medicate” — there’s also no thought evident of how the characters fit into their era. Specifically, Elizabeth’s a woman lawyer who must have got her degree at a time that would’ve been highly unusual. But there isn’t a sense of that background influencing her character.

You can see what the movie wanted to do, and that idea is strong: use the form of the ‘woman’s picture’ and a specific kind of period horror movie to talk about the sexism of that era and this one. But it doesn’t work. The film doesn’t understand its period well enough to evoke it beyond some elements of visual texture, and it doesn’t grasp how at least one of its chosen genres work.

You can see what the movie wanted to do, and that idea is strong: use the form of the ‘woman’s picture’ and a specific kind of period horror movie to talk about the sexism of that era and this one. But it doesn’t work. The film doesn’t understand its period well enough to evoke it beyond some elements of visual texture, and it doesn’t grasp how at least one of its chosen genres work.

Climate of the Hunter never does get around to explaining the meaning behind its title, and that’s oddly fitting. It’s an idiosyncratic movie, certainly, and you can feel a distinctive sensibility animating it. Unfortunately it doesn’t cohere into a solid story, despite assembling some decent character ideas and strong thematic concerns. The dialogue’s good, establishing character and conflict, forming solid dramatic scenes, and covering a lot of ground in the movie’s 90 minutes. But action’s infrequent, resulting in a talky picture that lacks a satisfying climax. You can see good ingredients here, and there’s no point where you drift away from the movie. Yet nothing adds up.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

A commendable reaction to the movie. I enjoyed it more (or, perhaps more precisely, thought that it did what it did better than you felt it did). The fact that I have nothing more to say about it nicely gels with your views here–some stuff happens, a bit of it is interesting, and then we’re done.