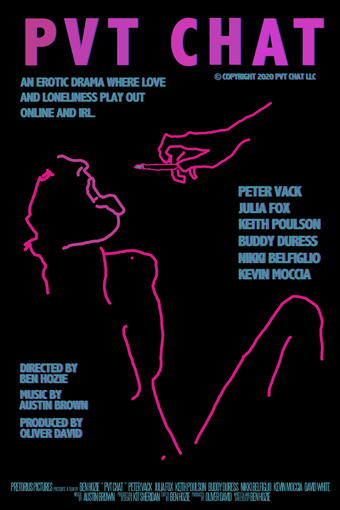

Fantasia 2020, Part V: PVT Chat

One of the new wrinkles to Fantasia this year is the existence of a Discord where filmmakers and critics and audiences can chat with each other about the movies playing the festival. It’s already proved quite useful to me, as seeing other people discussing films has helped draw my attention to a few titles I’d originally dismissed as uninteresting or out of step with this web site’s focus. A case in point was the movie I watched late on Fantasia’s second day, writer-director Ben Hozie’s PVT Chat.

One of the new wrinkles to Fantasia this year is the existence of a Discord where filmmakers and critics and audiences can chat with each other about the movies playing the festival. It’s already proved quite useful to me, as seeing other people discussing films has helped draw my attention to a few titles I’d originally dismissed as uninteresting or out of step with this web site’s focus. A case in point was the movie I watched late on Fantasia’s second day, writer-director Ben Hozie’s PVT Chat.

It’s got no element of the fantastic. But it’s a kind of crime story, and indeed from a certain angle is one of the damnedest film noirs I’ve ever seen. While also being sexually explicit (and what I am told the kids these days call kink friendly) to a surprising degree.

The film opens with Jack (Peter Vack), a young New Yorker, alone in his apartment masturbating. Jack spends a lot of time watching camgirls, and we hear him describing to them what he wants (“verbal abuse”) and setting up scenarios to play through. He finds a new girl, Scarlet (Juia Fox), who swiftly becomes his favourite. We find out that Jack doesn’t have much else going on in his life. He supports himself, barely, by playing online blackjack. He seems to be spiralling downward, so desperate for actual human contact he makes friends with the guy his landlord hired to paint his apartment. Then he thinks he sees Scarlet in a neighbourhood store. But Scarlet tells him she lives in San Francisco, and swears she’s never been to New York.

This first act of the movie is well-made and thoughtful, but a little slow, and I found it a bit difficult to care about at first viewing. It’s important for establishing Jack and his situation, though, and it does a solid job of making us question his grasp on reality — was he hallucinating? Or, even though he’s had moments of actual connection with Scarlet, is she lying to a john?

We find out as the movie suddenly sharply expands its focus. We follow other characters, and the story takes some new twists, opening up in unexpected ways. Thematically the film’s focus becomes clearer and more intricate. We get different angles on how the characters are telling stories of their lives, scripting and directing what they want and what they see. Jack’s already lied to Scarlet about his job, concocting an imaginary telepathic technology out of whole cloth. Without wanting to give too much away, we later find out how much she has lied and how much she has told the truth to him; we find out more about her art — she’s already shown him paintings she made — and about her job. As in 2018’s Cam, the parallel between film narrative and webcam porn is examined, both visual media involving scripted fictions.

Jack creates fantasies for Scarlet to play out, but we find out later that another male storyteller is exploiting her in a different and really more troubling way. More importantly, the apparent power relationship involved in the BDSM that Jack wants, and the more complicated power relationship of client and camgirl, is challenged. These are characters telling stories about themselves, and expecting other people to fit into those stories the way they’re scripted. But those other characters have a reality of their own. So Jack starts the film as an alienated and possibly psychopathic outsider, but the story follows the chance he has to develop an actual relationship with another person — even as Scarlet, structurally a femme fatale, gets to make her own choices.

Jack creates fantasies for Scarlet to play out, but we find out later that another male storyteller is exploiting her in a different and really more troubling way. More importantly, the apparent power relationship involved in the BDSM that Jack wants, and the more complicated power relationship of client and camgirl, is challenged. These are characters telling stories about themselves, and expecting other people to fit into those stories the way they’re scripted. But those other characters have a reality of their own. So Jack starts the film as an alienated and possibly psychopathic outsider, but the story follows the chance he has to develop an actual relationship with another person — even as Scarlet, structurally a femme fatale, gets to make her own choices.

There ism as I say, a noir aspect to PVT Chat — a man wanders the nighted streets of the big city, driven by obsession with a woman hiding secrets and lies, and we’re not sure who’s playing with who, or where the money ends up. But the resolution’s not about the money. It’s about the characters. I have no idea whether the sexual content will drive away viewers; personally as an asexual I found the movie as a whole thoughtful and tightly-structured. It’s got a lot on its mind. Nothing it does is for shock value. But it talks about sexual desires frankly, even while occasionally using genre ideas in unconventional ways.

There’s a stark look to the movie, low-fi, as though seen through a webcam. This works, and not just conceptually. There’s a disconcerting closeness, a feel like you’re watching something actual happening in real-time. Maybe above all, though, it’s a New York movie, shaped by images of the nighttime city — grungy, wasted, often soulless, filled with architecture and anonymity.

Much of it plays out in a world of bohemian artists, in grimy apartments and backstage areas. There’s a set of characters aspiring to some greater life, some other reality, a world of storytelling. And it’s a useful contrast with Jack, who doesn’t consciously have that, at least to start. But he knows what he wants from his camgirls. And by the end of the film he’s got something more; a purpose, at least, and that change in his character is the core of the film.

Much of it plays out in a world of bohemian artists, in grimy apartments and backstage areas. There’s a set of characters aspiring to some greater life, some other reality, a world of storytelling. And it’s a useful contrast with Jack, who doesn’t consciously have that, at least to start. But he knows what he wants from his camgirls. And by the end of the film he’s got something more; a purpose, at least, and that change in his character is the core of the film.

Jack torments himself throughout the movie with the idea that all human relationships are fundamentally exploitative. It’s the sort of idea that can’t really be proved or debunked — it’s really a question of which side of the argument you want to spend time justifying — but PVT Chat is a good work of drama that undermines the assertion as far as is possible.

The actors do some daring work here. Jack could have been unsympathetic to the point of being uninteresting, but Vack plays him in such a way that as we come to learn more about him and his past we see a bit of how he’s been shattered by recent events in his life. His experiences with Scarlet can be seen as representing a kind of healing. She’s a little bit more opaque, but Fox does a good job of presenting her series of facades in such a way that we at least think we can tell when she’s being honest. I’d say, in fact, that a lot of the final impact of the film depends on us being able to trust her at certain points, and I think Fox allows that to happen.

Nothing’s perfect, and some aspects of the film might have come out more. Notably, in an intriguing hour-long Q&A, the creators mentioned that Jack’s blackjack games were meant to symbolically echo the idea that a relationship’s a gamble; I didn’t get that from the film itself, meaning his profession felt thematically unconnected (though useful to the plot). Mostly, though, the movie does a strong job of playing with ideas of storytelling and indeed of collaboration. One way of talking about a connection between people, it suggests, is by showing their collaboration in fantasies they share and thus in rewriting the world.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.