Lovecraft in China: The Flock of Ba-Hui by Oobmab

|

|

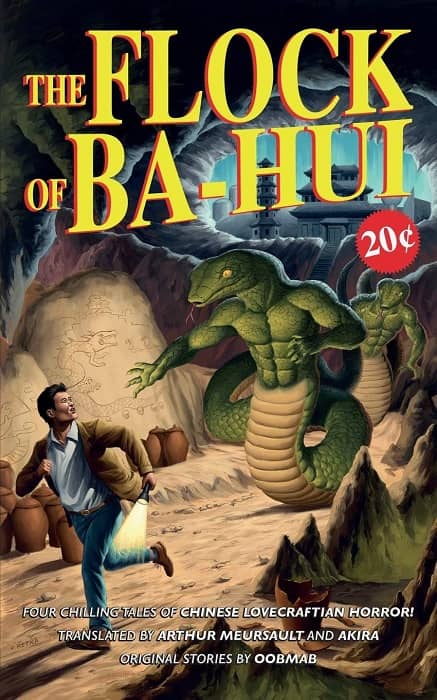

Cover by Roger Betka

The Flock of Ba-Hui and Other Stories

Oobmab (translated by Arthur Meursault and Akira)

Camphor Press (254 pages, $24.99 hardcover/$14.99 paperback/$6.99 digital, February 2020)

Beyond the protective barrier of Europe’s vast libraries, Latinate languages, aristocratic bloodlines, and imperial armies, there lurks a malign chaos of ancient knowledge and alien science. To our Western eyes, this chaos is a universe of black magic and monsters but there is, alas, much more to it than that, when one considers the full span of inhuman evil that extends from ancient creatures long outcast, brooding and breeding sinister vengeance in the Earth’s depths, to the latest incursions by loathsome entities whose blasphemous technologies have carried them to this green and innocent planet from the mist-shrouded globes circling the farthest stars.

This is essentially Lovecraft country: a universe that has become known as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Ever-fearful of dark forces from the outside, in daily life the American author H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) was an enthusiastic exponent of modernity – the expansion of northern European cultures throughout the world to the disadvantage, even appropriation, even erasure, of indigenous and non-European cultures. As America itself blossomed into an imperial power, Lovecraft’s United Empire loyalism (which to be fair, was greatly mitigated in his later years) envisioned a USA that “must ever remain an integral and important part [as he wrote at age 24] of the great universal empire of British thought and literature.”

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Lovecraft treasured his native New England not only for its green fields, stone churches, and stately mansions, but for the ways these things embodied the culture of an even-more-native England, a just and civilized seat of a white, English-speaking empire, an island across the sea that he felt linked to in spirit, although he never saw it in person.

Clearly Lovecraft’s work as a horror writer was only enriched by his aversion to the alien and the unknown. In everyday life, it’s small-minded and parochial to view foreigners as innately awful, but such a mindset is a great help to a horror writer if it enables them to project this sense of awfulness into a vision of an otherness controlled by forces which although of course evil, are also essentially unknowable, fascinatingly so in their very alienness and hugeness. Lovecraft may have been gradually overcoming these tendencies by the time of his death from cancer at the age of 46, but in the meantime his xenophobia (fear of the foreign) and orientalism (view of Asian cultures as irrational and exotic, even magical, rather than methodical and logical) enriched his talent for depicting the distant and the foreign as sources of mystery and menace. Since the most distant is the most suspect, in Lovecraft’s cosmology among all of Earth’s peoples, it is Asians who are the likeliest incubators of long-dormant evil.

In the years since Lovecraft’s death, his work has spread worldwide, and it seems that whatever the ethical shortcomings of Lovecraft’s world-view, Asians themselves have taken them with grace and good humour; perhaps because they are all too familiar with their own histories of xenophobic eruptions, but also because a literature haunted by the past is right up their alley.

“In China, we don’t go in for science fiction,” a graduate student from Yunnan once told me. “We prefer stories about the past, rather than the future.” In this case, it is perhaps no surprise that Lovecraft’s work has struck a chord with Chinese readers. Long-dormant evils, alien prehistories, hidden subhuman races waiting to re-emerge: these are the recurring tropes in the Cthulhu Mythos.

Here they are, back again, quietly waiting to undermine our souls, our sanities, the very underpinnings of our sane and peaceful everyday existences, in this collection of Lovecraftian stories by a Chinese writer of the nom-de-plume Oobmab (the name itself continuing a tradition of Lovecraftian proper names such as Yog-Sothoth or Ooth-Nargai, constructions that are eerie enough on the page, but almost comical if you actually say them aloud).

The book has been created by translators Arthur Meursault and Akira, who have also devised a clever framing device: a nameless narrator brings together, against their wills, four equally nameless characters – the Researcher, the Dreamer, the Historian, and the Anthropologist – each to relate their own story of an encounter with ancient evil.

In their introductions, the editors admit that, just as it was a considerable challenge to translate Lovecraftian language constructions and inventions into Chinese, it was not at all easy to translate Oobmab’s works into English. The fact that the resulting prose is sometimes a bit shall we say, infelicitous, is illustrated by the volume’s very title, The Flock of Ba-hui. “Flock” in English implies a more or less passive and contented gathering: a herd of sheep, a flight of birds, even a church congregation. One would think that “horde” or even “followers” have been a better word, certainly for a work of cosmic horror – but one trusts it is the most effective equivalent the translators could find, given the hard work, care and concern they show throughout the book.

If there is an occasional awkwardness in the prose, and even sometimes in the narrative (a wound on a character’s left hand on page 25 moves to his right hand by page 34), we might admit that a certain awkwardness is the charm of Lovecraftian language itself; to enjoy Ba-hui, one must enjoy spending time with a writer who describes a smell as “noisome ichthyoid” (awfully fishy) or granite blocks as “cyclopean” (awfully big).

An English reader might judge these as unfortunate archaisms if this were contemporary writing in English, but these words – deliberately Latinate, archaic and somewhat pretentious even when Lovecraft used them almost a century ago – gain new life when they are beamed from the early 20th century to the early 21st, and refracted through a Chinese man writing in his own language back to English again. A reader in English might very well enjoy the novelty of going to a Chinese writer to find references to “pseudepigrapha,” an “exuvium of the dragon,” an “ophidian creature,” or in a delightful mixture of English, Chinese, and Latin, a “lingzhi mushroom, of the ganoderma genus.”

The strength in Lovecraft’s narrative voice, of course, is its ability to convey the awe and horror of a lone human being coping with the gradually blossoming revelation of the existence of huge and inhumanly cold-hearted alien intelligences. That voice’s weakness was its inability to depict human relationships in any depth, and in The Flock of Ba-Hui, true to the Lovecraft style, there is practically no dialogue. In the title story, for example an enormous amount of exposition comes to us via descriptions of a series of ancient wall murals described from the viewpoint of essentially faceless explorers.

On the other hand, some descriptions are detailed and vivid; in particular, Oobmab shares Lovecraft’s sensitivity to architecture and his fastidiousness in describing it. In “The Ancient Tower,” for example, “standing halfway between the walls and the center of the room were eight immense stone pillars supporting the roof … smoothly polished and as thick as three people linking hands in a circle. The middle portion of the pillars was also thicker than the upper and lower ends …” etc.

Parts of the pleasure of The Flock of Ba-Hui, then, comes in the sense of revisiting the best aspects of Lovecraft’s handful of classic stories, and seeing them expanded into new territory. There are many echoes of Lovecraft’s original work – references to Yig, Hlanith, Ooth-Nargai, and even the eerie cry “tekeli-li” from “At the Mountains of Madness” – but Oobmab extends the mythos’ range of reference to include many Chinese works of art and literature, both real and imagined, to create a delightful patahistorical effect, and in such creatures as the taisui (certainly as yucky as anything Lovecraft ever devised) and the ba-hui (which build a plausible narrative bridge between the Chinese dragon and the Cthulhu Mythos), Oobmab has introduced new creations that fit perfectly into Lovecraft’s imaginative world.

One can go online, find a map of Qingdao, and follow some of the streets described in “Black Taisui,” including Longkou Road, although the absence of Google Earth coverage means we can’t actually zoom in to see what real-world building occupies the site of the Lao family’s cursed house at Number 5, its hidden cellar the access to a sprawling network of caves and tunnels concealing the insidious taisui.

In short, what an odd book! A book, however that, starting with Roger Betka’s masterful pulp-magazine cover artwork, to the framing story’s cosmic conclusion, not only offers something just a bit different than what the reader might expect, but consistently delivers what the reader needs: the sense of wonder that the best of H.P. Lovecraft’s work so often conveyed. In this era where so many writers (myself included) are remaking Lovecraft any way they want to, let’s welcome this writer – and applaud the editors/translators – for extending the Cthulhu mythos in directions that, one imagines, Lovecraft himself would have approved (did I say approved? – he would have been delighted).

David Neil Lee’s novel The Midnight Games was reviewed by Black Gate’s John O’Neill as “precisely what the world needs: an action-packed Young Adult Cthulhu Mythos novel.” The Medusa Deep, a sequel to The Midnight Games, will be published in fall 2020. His last article for us was Only the Monsters Can Save Us: Claude Debussy meets Godzilla. davidneillee.com.

And, of course, “Oobmab” is “bamboo” backwards…

I never noticed that!

Out of ‘infelicitous, Latinate, patahistorical and pseudepigrapha, ‘Xenophobia’ is What is defined for us ?

[…] Early this year the FB page Cha: An Asian Literary Journal announced the existence of a new book, The Flock of Ba-Hui, based on the works of H.P. Lovecraft, by the Chinese writer “Oobmab” (spell it backwards). I ordered a copy and wrote a review of the book for Black Gate Magazine. […]