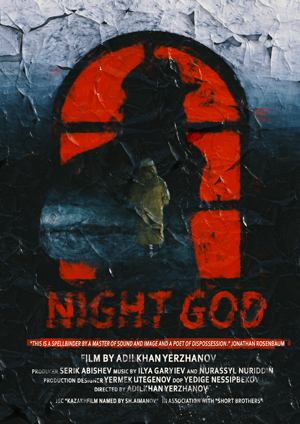

Fantasia 2019, Day 16, Part 1: Night God

My first film on Friday, July 26, was a Kazakh work playing at the de Sève Cinema. Written and directed by Adilkhan Yerzhanov, Night God is a particular sort of uncompromising. It’s a beautiful picture, but extremely slow, still, and self-consciously meditative. I was deeply moved, for all its studied avoidance of simple dramatic action.

My first film on Friday, July 26, was a Kazakh work playing at the de Sève Cinema. Written and directed by Adilkhan Yerzhanov, Night God is a particular sort of uncompromising. It’s a beautiful picture, but extremely slow, still, and self-consciously meditative. I was deeply moved, for all its studied avoidance of simple dramatic action.

A man (Bajmurat Zhumanov), his wife, and his daughter (Aliya Yerzhanova) arrive in an unnamed town, a post-industrial city ruled by a cadre of state officers. It’s dark and cold, with comets in the sky, and the people live in fear of the coming of the Night God who will destroy the world. The man’s ordered to report to the local TV station to act as an extra, in exchange for which he’ll be given a house; this sets off a chain of serio-comic misadventures that must be called ‘kafkaesque’ if that word is to have any meaning.

A fake bomb’s strapped to his torso as part of a game show. But the bomb turns out to be real. He asks to have it removed. But before that he has to get an imam to sign a document attesting that he isn’t a radical. Thematically, then, there is a faith present in the film implicitly opposing the belief in the Night God; but all along the way the movie’s speaking of the struggle to believe in anything in a world that is feral and, to all appearances, meaningless.

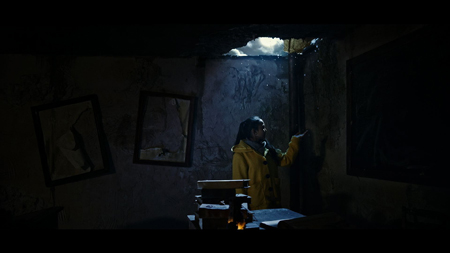

The first thing one notices about the film is its intense visual beauty. It’s a mix of beautiful shadows and beautiful light. Taking place in an endless night, illumination is nevertheless powerful, bringing out colours and detail. We see every crack in every wall, every mote of dust; and this city is filled with cracks and dust. Although apparently shot entirely in studio, the town feels like a real place, looks like a real city coping with decayed industries and a collapse of central government. There are no screens or phones, and it feels right that a television station, the old technology of an earlier age, is central to the story.

That sheer sensory power is important, because the movie’s based mostly on very long takes with no or minimal camera moves. That is, the camera moves enough to give a very subtle sense of personality to the scene; not a sense of threat, as can happen with long tracking shots, but a kind of curious meditative feel, as though the camera is shifting ever-so-slowly to get a better idea of what’s happening. The soundtrack’s minimal, mostly a soundscape of whistling winds and water dripping from some unseen broken pipe. We’re stuck staring at what the movie insists on, and fortunately that is often beautiful in the way that inorganic decay and abandoned things can be beautiful. It has been said that the film has a painterly visual sensibility, and this is true. A statue, a clock without hands, a grated floor with light rising through it, come to feel like powerful statements hinting at a symbolism more profound than can be easily stated.

This is furthered by the tendency of the actors to underplay their roles. That’s not universal; sometimes a character emotes when their life is threatened, or their faith undercut. But in general this movie’s less concerned with being a well-made dramatic work than with exploring themes of the absurd. Moment to moment, what is happening has a kind of logic. But as a whole it’s hard to view it as a coherent story even if events ape the structure of story.

This is furthered by the tendency of the actors to underplay their roles. That’s not universal; sometimes a character emotes when their life is threatened, or their faith undercut. But in general this movie’s less concerned with being a well-made dramatic work than with exploring themes of the absurd. Moment to moment, what is happening has a kind of logic. But as a whole it’s hard to view it as a coherent story even if events ape the structure of story.

Once can say Night God has a post-Soviet feel. A community ruled by outsiders now cut off from their nominal source of authority, ruling by habit as much as firepower; a pervasive bureaucracy, which operates by its own logic and worldview; slightly antiquated technology, and crumbling infrastructure. Add to this humans being cruel to each other, and Gods spoken about but absent, appearing perhaps only to stage an apocalypse. If you’d asked me to list off what I’d expect in an art film from eastern Europe, it would be much of the foregoing along with lines like “You are senselessness, you are absurdity.”

Still, the movie feels new and challenging. We are also told “If you think, you resist.” I have an idea that the emphasis on the visual power of the film subliminally emphasises what is new: modern filmmaking technology, digital cameras that capture colour and light in a way different from film. Night God is blunt in its themes, in its dialogue and voice-over, but there’s a fluidity and power in what unfolds onscreen that is novel.

This movie is startlingly imaginative in its depiction of its reality, and by that I mean that the way the town is conceived and the things within it are unusual and shot in a distinctive way. The TV station’s a source of perpetually striking imagery. A run-down police station feels like nothing else but what it is. A mosque is filled with odd little rooms that make a distinctive setting for a number of scenes about memory and faith. And when we think we’ve seen everything the film has to offer, it opens up near the end with a range of new sets and new images. That rhythm of adding new things, new sights, creates a credible world and indeed universe: there is always something more, coming when you don’t expect it, producing some new image that just happens to be perfect in the precise way the light falls.

This movie is startlingly imaginative in its depiction of its reality, and by that I mean that the way the town is conceived and the things within it are unusual and shot in a distinctive way. The TV station’s a source of perpetually striking imagery. A run-down police station feels like nothing else but what it is. A mosque is filled with odd little rooms that make a distinctive setting for a number of scenes about memory and faith. And when we think we’ve seen everything the film has to offer, it opens up near the end with a range of new sets and new images. That rhythm of adding new things, new sights, creates a credible world and indeed universe: there is always something more, coming when you don’t expect it, producing some new image that just happens to be perfect in the precise way the light falls.

What’s it about? I would say about faith and death and apocalypses individual and collective; and about the absurd, about the conflict between seeking a meaning that ends in nothing, and a deeper kind of nothingness. But for better or worse, the themes that stick with me from this film are not necessarily the themes that are clearly enunciated. There’s a power to the movie that extends beyond the perhaps over-weighty or too-obvious meaning the dialogue suggests. Or, to put it another way, the dialogue may bluntly focus the film’s meaning, but the real sense of apocalypse and dreadful absurdity comes from the imagery and not the drama.

As such, it’s the sort of art where it feels pointless to declare it a success, or to say that not everyone will care for it. It merely is, intensely. I found it deeply affecting in ways I can’t describe. I hope other people who see it will have some similar reaction. I think if anything I’ve written sounds interesting then it’s at least worth a look; this is a film that has the potential to be transformative to its viewers, I think, in a way that few do.

As such, it’s the sort of art where it feels pointless to declare it a success, or to say that not everyone will care for it. It merely is, intensely. I found it deeply affecting in ways I can’t describe. I hope other people who see it will have some similar reaction. I think if anything I’ve written sounds interesting then it’s at least worth a look; this is a film that has the potential to be transformative to its viewers, I think, in a way that few do.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I think the most salient point this movie made about militaristic bureaucracy happened toward the end (?) when a pair of commissars are gunned down and immediately replaced — as in, their replacements walk on to the scene and sit right down at the dead officials’ barely vacated desks. “That says something” would be a bit of an understatement.

I am very glad to have seen “Night God”, but am personally in the awkward position of having to couch whatever recommendation I’d make about it in the terms of, “it’s a good movie to Have Seen”. I was never bored during it, but never felt fully gripped. I don’t know if you saw the Chinese film, “Free & Easy” that played…in 2017, I think. It had a comparable feel, but was, after digging below the often staggered and static nature of the “action”, actually a screw-ball comedy, but one played out in slow motion, so to speak.

I would shell out a lot of money, though, for any of the neon signs from the city. “Night God” always looked Good.

Oh man, did it look good! (And I loved that bit with the bureaucrats.)

I get what you mean about a good film to Have Seen, but I think I was involved more in the theatre than you were. It is fairly long, and that pace over almost two hours becomes a little rough. But for whatever reason, it worked for me.

The Free and Easy comparison’s a good one, though. Another film set in a post-communist small city with decaying infrastructure and violent officials in charge …