Hither Came Conan: Mark Finn on “The God in the Bowl”

Welcome back to the latest installment of Hither Came Conan, where a leading Robert E. Howard expert examines one of the original Conan stories each week, highlighting what’s best in it. Today, it’s Howard biographer Mark Finn looking at one of the first stories, “The God in the Bowl.” And here we go!

Welcome back to the latest installment of Hither Came Conan, where a leading Robert E. Howard expert examines one of the original Conan stories each week, highlighting what’s best in it. Today, it’s Howard biographer Mark Finn looking at one of the first stories, “The God in the Bowl.” And here we go!

The God Has a Long Neck

“The God in the Bowl” is part of the holy trinity of Conan stories. No, not “Tower of the Elephant,” “Red Nails,” and “Beyond the Black River” (though they are undoubtedly worthy of the appellation). I’m talking about the Original Trinity, the Big Three, the initial stories that Robert E. Howard wrote and submitted to Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales back in 1932.

I consider these stories to be Ground Zero for the essence of Conan the Cimmerian as he was originally introduced. In “Phoenix on the Sword,” we meet Conan the King, an established old campaigner, with a whole lifetime of stories under his furrowed brow, struggling with his new role as a king. This was borne out of Howard’s desire to write fiction in the guise of history; tales of adventure and sweeping consequences, without having to fact-check and sideline his narrative vision. Using his unpublished Kull story, “By this Axe, I Rule!” as a jumping off point, Howard clearly had an idea of what he wanted to do.

But he had to sell it to the market that was buying, and since Oriental Stories, the magazine he’d been selling his historical adventures to, had shuttered its submission window, he turned to his old standby, Weird Tales. “The Unique Magazine” under the editorial direction of Farnsworth Wright enjoyed a kind of nebulous distinction as a kind of catch-all for any kind of story, so long as it was weird. This included anything with a spicy suggestion, such as ice maidens wearing gossamer robes and taunting a battle-exhausted youth. “The Frost Giant’s Daughter” was made for Wright, who would recognize its classical mythic underpinnings, but would also not mind the implied slap-and-tickle of the naked girl laughing at young Conan.

But “The God in the Bowl”…ah, therein lies the final key ingredient to the essential salts that went into the golem of Conan, and that metaphor is apt because like the avenging spirit of the city of Prague, Conan would be Howard’s champion against the encroaching forces of civilization. Conan became Howard’s antidote in print, saying what he couldn’t say, and doing what he couldn’t do, and also a safe haven during his three year-long argument with H.P. Lovecraft on the merits of barbarism vs. civilization that ran nilly-willy through their correspondence. In the Conan stories, Howard had a free hand to not only espouse his opinions of what barbarism meant to him, but he could also redress the myriad wrongs of civilization by having his title character rend them asunder.

It all started with “The God in the Bowl.”

I’ve said before that Farnsworth Wright was a capricious editor, and here is a perfect example. He may or may not have read Howard’s historical essay of the Hyborian Age, but if he did, he was unmoved by it. He rejected The Frost Giant’s Daughter outright, saying “he did not care much for it.” He wanted some changes made to “The Phoenix on the Sword,” and he likewise rejected “The God in the Bowl.” Two of the three Conan stories, intending to set up a new series, torpedoed with little more than an epistolary shrug. It’s a good thing Howard was on a roll, or he might have dropped the idea and tried something else.

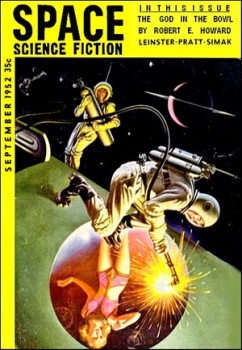

That means most people’s earliest exposure to “The God in the Bowl” happened on L. Sprague de Camp’s watch. As the steward of Howard’s Conan, de Camp made hay while the sun shone, and he published and republished his edited version several times over (a science fiction mag in 1952, a Gnome Press edition in 1953, and of course, a Lancer paperback in 1968), before Donald Grant published a corrected text in his famous line of Conan hardcovers in the 1970s.

For years, people—fans, scholars, and experts alike—have taken pot shots at this story, claiming it’s heavy on exposition and slight on action, or dismissively decrying that the story is Howard’s “attempt” at a Hyborian Age mystery. Some critics have more charitably likened it to a Dashiell Hammett Continental Op crime story, and while there are some parallel comparisons that line up, I think that “The God in the Bowl” is about as much of a mystery as Howard’s earlier story, “The Blood of Belshazzar.” The story is not a whodunnit, but more of a howdoit; i.e. this is how civilized men do it, and by contrast, this is how barbarian men do it back.

Specifically, Howard lays out his view of civilization, taking nothing away from the grandeur of Numalia, nor its inhabitants. But in drilling down and meeting them face to face, the true nature of these great men is revealed, and when compared against a young, sullen Cimmerian thief—who doesn’t lie, speaks plainly, and doesn’t tattle—then the deficiencies of modern men are all the more emphasized. No, “The God in the Bowl” isn’t a very good detective story, but that’s not what Howard was doing. He was making a point about crime and punishment, about the fairness of the legal system, about power and corruption, and about how the rich view the poor.

Consider how quickly Conan confesses to the crime he was attempting to commit—simple burglary, for the purpose of obtaining coin for food. Shades of Hugo and Dostoevsky, rather than Doyle and Poe. It’s too bad for Conan that a larger crime was committed while he was attempting his smash-and-grab, because that’s what brings the city watch. They take one look at Conan and see that he is an outsider, a foreigner, and a barbarian at that, and waste no time trying to pin the murder on him. Only the inquisitor, who is, by comparison, the lesser asshole of the group, even attempts to investigate the crime before sentencing Conan to death.

I would never argue that “The God in the Bowl” has the same narrative sweep as “People from the Black Circle.” After all, this was the third Conan story ever written. To borrow a turn of phrase, “he got better.” But there is a weird menace element to this story, perhaps not a smoothly disseminated as in other stories, that takes the form of a slow burn, both in terms of plot and character. Conan goes from sullen to seething as the city-bred authorities wag their tongues and talk around the barbarian as if he’s not in the room. It’s not a locked room mystery, as some have suggested. The museum is not a pristine environment. After all, Conan got in easily enough.

I would never argue that “The God in the Bowl” has the same narrative sweep as “People from the Black Circle.” After all, this was the third Conan story ever written. To borrow a turn of phrase, “he got better.” But there is a weird menace element to this story, perhaps not a smoothly disseminated as in other stories, that takes the form of a slow burn, both in terms of plot and character. Conan goes from sullen to seething as the city-bred authorities wag their tongues and talk around the barbarian as if he’s not in the room. It’s not a locked room mystery, as some have suggested. The museum is not a pristine environment. After all, Conan got in easily enough.

No, there’s an element of dread to this story, a component that is glossed over because of the structure of the story; everyone talks for several pages, and they threaten Conan with a beating or worse, and when Conan has had all he can stand—his employer sells him out, pretending not to know him—well, the three paragraphs of carnage happen so fast, it’s breathtaking.

Conan beheads his employer, stabs the inquisitor in the thigh (he was aiming for his junk), cuts off another’s ear, plucks out an attacker’s eye, and kicks and stomps another guard. In three short paragraphs. What they lack in ferocity, they more than make up for in savage brutality. And as cathartic as it may be, both for the reader and Our Favorite Barbarian, the best, or rather, the worst, is yet to come.

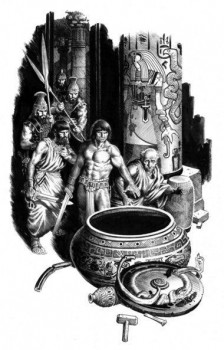

The mystery of the corpse is intensified when, in a plot device straight out of, oh, I don’t know, Weird Tales, the guard dies of fright, but not before he cackles madly at the unhinged revelations his mind was forced to accept. “The god has a long neck! Ha! ha! ha! Oh, a long, a cursed long neck!” He dies, grinning, like Conrad Veidt, and that’s enough to clear the room of everyone save Conan. He enters the chamber and is confronted with the Child of Set, what we would call in Dungeons and Dragons days a Naga, a giant serpent with the head of a beautiful woman atop it, both inhuman and alluring. Conan succeeds in overcoming her charming command and escapes with a desperate swing of his sword, running from the museum and the city.

It’s an abrupt ending, and easy to gloss over, because the last words in the story are “gigantic serpent,” and that’s what many take away from the story. Not to put too fine a point on it, but dismissing the child of Set is a lot like calling Cthulhu an invisible whistling octopus.

If there’s any fault to leaven on anyone where this story is concerned, it’s in Farnsworth Wright not getting what Howard was trying to do. Even if he’d asked Howard to tighten or expand or otherwise alter the story, we might have gotten a series of adventures with Thoth Amon dogging Conan’s career. Instead, we got what we got. And while “The God in the Bowl” wasn’t initially part of the Weird Tales Conan stories, it has since been restored to its rightful place, at both the beginning of Conan’s career and Robert E. Howard’s foray into his invented mythical historical epoch. It’s not “Red Nails,” and it doesn’t have to be, either. “The God in the Bowl” will forever be Conan’s introduction to civilization, and that interaction will impact Conan’s career as a thief, a mercenary, and even as a king, leading to some of the best, most interesting and appealing parts, of Robert E. Howard’s sword and sorcery tales.

From the Dusty Scrolls (Editor comments)

The story was written in 1932. L. Sprague de Camp’s edited version appeared in the September, 1952 (Volume 1, Number 2) issue of Space Science Fiction magazine. The original Howard text would not be seen until Donald Grant’s 1975 The Tower of the Elephant collection.

de Camp wasn’t much of a fan of this one, writing, “The God in the Bowl tries, not very skillfully, to combine adventure-fantasy with a detective story.”

H.P. Lovecraft enjoyed it more, written on a calendar pad, “The climax of The God in the Bowl is splendidly vivid!”

With two of the first three stories rejected (and the only one accepted being a rewrite of a previously unsold tale), it does not seem far-fetched to think we are lucky Howard didn’t simply give up on Conan and move on to the next character he could earn much-needed money from.

This story cries out for a long essay on the disparities of justice in the Hyborian age, with correlations to today.

I looked at this story as a very early police procedural in a Black Gate essay.

Marvel adapted this story as “The Lurker Within” in Conan the Barbarian #7, in July, 1971. Roy Thomas commented in Barbarian Life, “Curiously, “The God in the Bowl” contains more dialogue, and probably less action, than any other Conan story. If we were to do an audio adaptation of the Conan stories, this one would give us the fewest problems.”

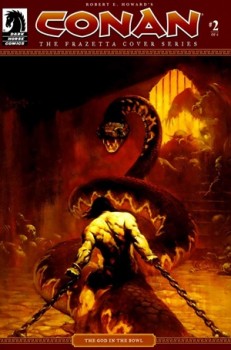

Dark Horse adapted the story in issues 10 and 11 of Conan, in November and December of 2004.

Prior posts in the series:

Here Comes Conan!

The Best Conan Story Written by REH Was…?

Bobby Derie on “The Phoenix in the Sword”

Fletcher Vredenburgh on “The Frost Giant’s Daughter”

Ruminations on “The Phoenix on the Sword”

Jason M Waltz on “The Tower of the Elephant”

John C. Hocking on “The Scarlet Citadel”

Morgan Holmes on “Iron Shadows in the Moon”

David C. Smith on “The Pool of the Black One”

Dave Hardy on “The Vale of Lost Women”

Bob Byrne on Dark Horse’s “Iron Shadows in the Moon”

Jason Durall on “Xuthal of the Dusk”

Scott Oden on “The Devil in Iron”

James McGlothlin on “The Servants of Bit-Yakin”

Fred Adams on “The Black Stranger”

Stephen H. Silver on “Man Eaters of Zamboula”

Keith J. Taylor on “Red Nails”

Ryan Harvey on “Hour of the Dragon”

The Animated Red Nails Movie that Never Happened

Up Next Week – Bob Byrne on “Rogues in the House”

Mark Finn is an author, actor, essayist, and playwright. His biography, Blood and Thunder: The Life and Art of Robert E. Howard, was nominated for a World Fantasy award in 2007. His articles, essays, and introductions about Robert E. Howard and his works have appeared in publications for the Robert E. Howard Foundation, Dark Horse Comics, Boom! Comics, The Cimmerian, REH: Two-Gun Raconteur, The Howard Review, Wildside Press, and he has presented papers about Howard to the PCA/ACA National conference, the Authors and Writers Conference, and lectures and performs readings regularly.

When he is not working in Howard Studies, he writes comics and fiction, dabbles in magic, acts as a creative consultant for media companies, and produces and performs community theater. He lives in North Texas with his long-suffering wife, too many books, and an affable pit bull named Sonya.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!).

He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

And he is in a new anthology of new Solar Pons stories, out now.

A good exploration, especially when coupled with Bob’s previous piece on the same story (which I read with interest when it first came out on Black Gate). Rather than argue that “The God in the Bowl” is the BEST Conan story, Mark makes the more interesting point that it’s one of the seminal ones, an insight cogently made and which would be difficult to dispute. I’m certainly not going to dispute it.

Poor old L. Sprague de Camp’s name gets trotted in again, but thankfully just for a general dig rather than the customary savaging. Possibly because the editorial change he’s most famous for in regard to this story can actually be seen as an improvement. (Sacrilege, I know, to say that ANY editorial alteration of ANYTHING Howard wrote might have been for the better. But I remain an obstinate heretic.)

Not sure what the distinction Mark makes here between ferocity and savage brutality is. It seems one without a difference, unless it’s that the results of the former are depicted as the latter. Perhaps we have become so used to our fantasy barbarians killing quickly and cleanly (or at least without much visceral description) that we’re able to put aside the actual physical consequences. Howard, however, is a much more visual writer than many. He has a way of putting you at the scene, and here, where he’s still establishing Conan as a character, he’s careful to omit nothing, even if he hasn’t found the fine balance between words and deeds yet.

In later tales, of course, he did, and we got (to steal from Toby Keith) “a little less talk and a lot more action.”

Thank you, Mr. Finn; nicely done. You’re more generous than I would be in calling Farnsworth Wright ‘capricious’; I’ve always enjoyed this story and I don’t understand why he rejected it.

I found Bob’s take on this story as a police procedural to be persuasive but I agree with your placement of this story in the context of the debate between Howard and Lovecraft.

I do disagree about one thing: the godling in the bowl is male, not female. Howard never uses the feminine when speaking of it, and I feel he would have certainly done so if it was a Daughter of Set.

Excellent discussion, and worthy attempt. Great job.

Between this and ‘The Tower of the Elephant’ as introductions to civilized mankind, I’m surprised Conan ever got involved with anything beyond the Red Districts of any city.

Nice write-up, Mark.

A good point, Jason. But we mustn’t fall into the trap of Tor Pastiche Syndrome, in which Conan can’t even throw a rock without striking a sorcerer. Magic in the Hyborian Age, as well as the modern era, is presumably RARE. There’s a reason Conan keeps getting surprised by it, and a reason we only have a couple dozen Conan tales by Howard. These are Conan’s “weird” tales, the recollections he’ll recount around a campfire, the occasional, exiting times he actually encountered the inexplicable and had somehow to deal with it.

We never hear about his petty thefts where everything went right, his mercenary campaigns in which the whole army WASN’T slaughtered except for Conan himself (and from which he actually got released and paid off when they were done with), or all the times he went to the bathroom, or slept alone, or had a drink in a pub and NOTHING HAPPENED.

I have a feeling much of his introductory excursion through the civilized countries went just fine. Or fine enough that he figured “I can handle this. I’m only going to find myself in shit too deep to cut my way out of maybe, one time in five.”

Besides, there are dangerous hidden gods everywhere. For every elephant in a tower or snake in a jar in the civilized world, there’s bound to be some bloodthirsty frost nymph casing a northern battlefield!