The Golden Age of Science Fiction: 2001: A Space Odyssey

|

|

|

The Balrog Award, often referred to as the coveted Balrog Award, was created by Jonathan Bacon and first conceived in issue 10/11 of his Fantasy Crossroads fanzine in 1977 and actually announced in the final issue, where he also proposed the Smitty Awards for fantasy poetry. The awards were presented for the first time at Fool-Con II at the Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas on April 1, 1979. The awards were never taken particularly seriously, even by those who won the award. The final awards were presented in 1985. The Film Hall of Fame Awards were not presented the first year the Balrogs were given out, being created in 1980. The SF Film Hall of Fame was given to two films each in its first and final years.

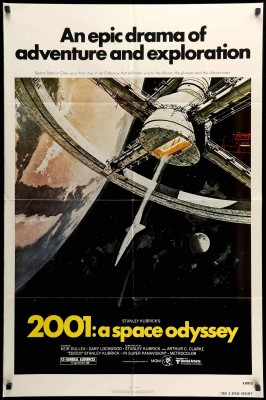

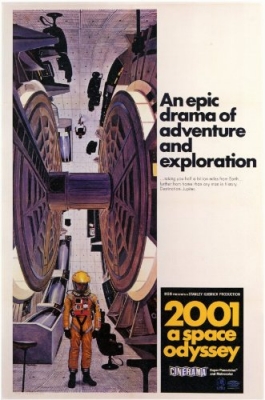

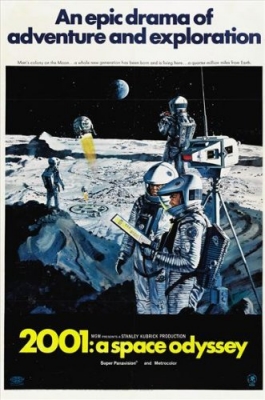

Filmed by Stanley Kubrick and based on several short stories by Arthur C. Clarke, 2001: a space odyssey was released to theatres in April of 1968, it was nothing like the B science fiction films which preceded it. Kubrick, guided by Clarke, attempted to make a realistic portrayal of space flight, even if it did have an ending that would appeal to the drug culture of the period.

There is no debate that 2001 is a slow moving film. Kubrick spends much of the film with long, languishing shots, showing the black monolith in prehistoric Africa, on the moon, or floating in space. He spends a tremendous amount of time depicting proto-humans in an arid Africa, the only dialogue unintelligible grunting noises as the hominds go about their daily lives, searching for food, fighting each other and fending off leopard attacks. Eventually, the first monolith shows up to bring enlightenment to the hominids. Interestingly enough, given Clarke’s strong support of scientific progress and his frequent disparagement of religion, the monolith serves as as the snake in the Garden of Eden. The minor squabbles of the hominids turn deadly as soon as they achieve the use of tools.

In one of the most famous sequences of the film, a thrown bones, used to kill a tapir-like beast in prehistoric Africa, morphs into a pan am spaceship arriving at a way station between Earth and the Moon, carrying Heywood Floyd to the moon to examine a second monolith found millions of years after the first. This section of the film, set on the space station and on the moon, introduces not only the concepts of the film, but also actual dialogue that the view can understand. Even as Kubrick shows the wonders of space travel and zero-G, using realistic special effects that far surpassed those of previous films, he also manages to make space travel banal. The flight to the space station and the flight to the moon bear a strong resemblance to flights on commercial airliners. While on the space station hundreds of miles above the earth, Floyd must go through security, meets up with colleagues, and calls home to his daughter. Even on the moon on their way to see the monolith, the main question asked is which type of prepackaged sandwich each person wants for lunch.

Following the monolith on the moon coming to life, the action, such as it is, transferred to Discovery, a spaceship crewed by five humans, three of whom are in cryosleep, and an advanced AI, the HAL 9000 computer. Kubrick shows Frank Poole and David Bowman handling the minor details of flying the spaceship and spending their time working out, playing chess, and exchanging time-delayed messages with people back on Earth. The ennui of space travel is palpable, exacerbated by the dampening of sound Kubrick employs.

The final section of the film is the part that throws most people, trying to figure out what Kubrick is showing as David Bowman once again comes in contact with a monolith, which boosts him to the next evolutionary level through an images of himself as an old man in a sterile hotel room and eventually the “Star Child.” As with the first section of the film, there is no understandable dialogue in this last section.

And yet, the film is a masterpiece. The slow pacing and boredom in space allow the viewer to be lulled into a sense of complacency. When the first crisis arises and Frank Poole goes outside to fix the AE-35 unit is as much a surprise to the viewer as it is to the astronauts. Kubrick’s decision to show the results with no sound are both a method of distancing the action and making it even more horrific. Bowman is then trapped in the haunted house of Discovery, facing off against the HAL 9000. The terror builds just as slowly as everything else in the film and Bowman’s exploration of the third monolith in orbit around Jupiter almost comes as a catharsis, albeit one punctuated by the trippy final sequence.

The strength of the film comes from the realism. Alien may have coined the tagline “In space, no one can hear you scream,” but eleven years earlier 2001 really brought the notion to the screen, showing absolutely silent scenes in space, or scenes with only the equipment sounds or breathing. The special effects were among the best in the industry, even in a world where CGI has replaced practical effects and models, the shots in 2001 hold a realism rarely matched.

The film is not to everyone’s tastes, which is understandable when cinema and television have a tendency for sharp, quick cuts, vast explosion, and not-stop action. 2001 did not presage the blockbusters of the 1970s which introduced the modern science fiction film, but rather hearkens more to the suspense film created by Alfred Hitchcock.

For the first year of the SF Film Hall of Fame, 2001: a space odyssey tied with Star Wars in a field which also included Alien, The Black Hole, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Dark Star, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Forbidden Planet, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Metropolis, Planet of the Apes, Silent Running, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, The Thing, Things to Come, and The War of the Worlds, only two of which, Forbidden Planet and The Day the Earth Stood Still, would win the award in subsequent years.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

I have to be in EXACTLY the right frame of mind to watch 2001, but when I am, it’s a stunning achievement.

And the recent 4K disc, viewed on my 4K TV, was magnificent.