Hither Came Conan: Scott Oden on “The Devil In Iron”

There is a weird synchronicity at work, here, Gentle Readers. Between the time when Bob Byrne solicited a few of us for this series and him handing out our story assignments, I wrote a Conan novella for Marvel (currently being serialized in the pages of the renewed Savage Sword of Conan, over a span of twelve issues). Specifically, it is a sequel to Robert E. Howard’s “The Devil in Iron”. Then, a few days later, I received my randomly selected story assignment from the good Mr. Byrne. My story? “The Devil in Iron.” Thus, the gods have spoken . . .

“The Devil in Iron” marked Howard’s return to the Hyborian Age after an absence of about six months. Written in the autumn of 1933, it employs a technique common to pulp-era writers in that Howard cannibalized plot elements of his own previous stories – the eerie resurrected villain á la “Black Colossus” (also used in The Hour of the Dragon); the greenish stone ruins from “Xuthal of the Dusk” (AKA, “The Slithering Shadow”); the sentient iron statues from “Iron Shadows in the Moonlight”; and even stylistic echoes from “Queen of the Black Coast.”

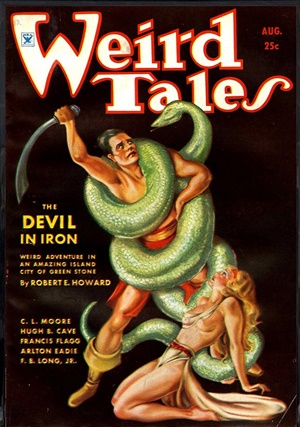

Howard sent the story off to Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales, who accepted it for publication on December 14, 1933. It appeared in the August 1934 issue. The story was lurid enough to take top billing, with Margaret Brundage providing one of her signature covers – this one depicting a rather anemic-looking Conan against a black background, struggling in the grips of a giant serpent while a gauzily-clad woman swooned at his feet. Hugh Rankin illustrated the story itself.

It is a fairly straightforward tale, if a bit formulaic. According to both Patrice Louinet and Howard Andrew Jones, who are scholars of Howard and his sources, it’s one of the few stories of the Conan canon that displays the clear and overt influence author Harold Lamb had over Howard.

Lamb wrote primarily for Adventure, his tales of Cossacks and crusaders fitting nicely with the works of Talbot Mundy, Rafael Sabatini, Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur and Farnham Bishop, and Arthur D. Howden-Smith. These were Robert Howard’s inspirations – writers of what we’d call today pure historical fiction. REH wrote what he knew he could sell, or what he believed had a good chance of selling; though he’d rather have spent his days writing the kinds of tales he loved from Adventure, it was proving a difficult market to break into. But, he knew by adding a splash of the Weird to the same rollicking adventure yarns, Weird Tales’ editor Farnsworth Wright would more than likely buy it.

Thus, in “The Devil in Iron”, Lamb’s Cossacks have become kozaks, and we discover that Conan the Cimmerian has fought his way to prominence among them, becoming their hetman or chief – and a thorn in the side of the King of Turan. The story takes place along the southern coast of the Vilayet Sea, and centers on the efforts of Jehungir Agha, the lord of Khawarizm, to trap and kill the Cimmerian before his own head winds up on the chopping block. The Agha’s councilor, Ghaznavi, has taken their foeman’s measure:

“For every beast and for every man there is a trap he will not escape,” quoth Ghaznavi. “When we have parleyed with the kozaks for the ransom of captives, I have observed this man Conan. He has a keen relish for women and strong drink. Have your captive Octavia fetched here.”

Octavia is an attractive woman, a Nemedian taken in one of Turan’s ceaseless campaigns against the Hyborian kingdoms of the West. With her as bait, Ghaznavi’s plan is to lure Conan to an uninhabited island called Xapur, just off the Vilayet coast, where the Agha’s soldiers can hunt him down “with bows, as men hunt a lion.” Though Octavia protests, threats of torture silence her and the plan moves forward.

In my opinion, Octavia’s finest moment takes place off-screen, alluded to as she gets into position to act as the piece’s damsel-in-distress. You see, Ghaznavi’s plan never required Octavia to actually be on the island of Xapur. No, once she had caught Conan’s eye at the prisoner exchange outside Fort Ghori – and once Ghaznavi’s subterfuge had worked its spell – Octavia’s use to Jehungir Agha was at an end.

“[W]ith deliberate fiendishness Jehungir had given her to a nobleman whose name was a byword for degeneracy even in Khawarizm.” So in an act of self-preservation, and one that marks her as a heroine who is a cut above the usual fare, Octavia engineers her own escape from Jelal Khan’s clutches. Then, by a coincidence which strains credulity, she winds up on Xapur the night before Conan arrives and is promptly captured by some unseen enemy.

Xapur is the perfect place for Jehungir Agha’s ambush as it has no beaches. It rises sheer from the water, accessible only by a rock-cut stair; it is jungle-clad and dotted with ruins of greenish stone – the bones of a forgotten civilization. But, as we see in the first chapter, it’s also the source of the story’s Weird element, as it’s home to a thing from the Outer Dark, “the being men called Khosatral Khel which crawled up from Night and the Abyss ages ago to clothe itself in the substance of the material universe.”

The lion’s share of demons inhabiting Howard’s universe take on ghastly shapes, blasphemous and maddening. Not so Khosatral Khel. His guise is that of a man, albeit a giant, with black hair, broad of shoulder and muscular – and whose perfect seeming flesh is wrought of living iron, as resistant to harm as Greek Achilles after his mother bathed him in the River Styx.

But it is a universal truth of the Hyborian Age that no matter how powerful or impervious a being may seem, it will have a chink in its armor, a flaw its enemies can exploit that leaves it open to doom and red ruin. And the terrestrial iron that comprised Khosatral Khel’s mighty form was useless against iron of extraterrestrial origin. Thus, his doom was a knife, “a curious dagger with a jeweled pommel, shagreen-bound hilt, and a broad crescent blade,” forged “of a meteor which flashed through the sky like a flaming arrow and fell in a far valley.” But, rather than using it to send his demonic essence back to the Abyss, Khosatral Khel’s ancient enemies used the knife to imprison him, to hold him “senseless and inanimate until doomsday.”

It is a simple fisherman who ends Khosatral Khel’s untold ages of ensorcelled slumber, one of the Yuetshi, the indigenous folk who dwell along the coast of the southern Vilayet Sea. A fierce storm drives this hapless fellow’s boat onto the rocks surrounding Xapur, and he seeks shelter among the green-stone ruins. There, he discovers a tomb broken open by a blast of lightning. He spies Khosatral Khel’s long-slumbering form inside. But it is the knife laid across the devil’s breast that draws this simple man’s eye. He slips inside, lays claim to it . . . and in so doing breaks the spell imprisoning Khosatral Khel, who repays the man by breaking his neck.

“The Devil in Iron” is the odd tale where Conan himself does not physically appear until the story is well underway, though his presence looms over all. But when he does take center stage, finally, at the beginning of Chapter Four, it is in Howard’s grand style:

“As the first tinge of dawn reddened the sea, a small boat with a solitary occupant approached the cliffs. The man in the boat was a picturesque figure. A crimson scarf was knotted about his head; his wide silk breeches, of flaming hue, were upheld by a broad sash which likewise supported a scimitar in a shagreen scabbard. His gilt-worked leather boots suggested the horseman rather than the seaman, but he handled his boat with skill. Through his widely open white silk shirt showed his broad muscular breast, burned brown by the sun.”

From the weed-choked bank, Jehungir Agha and his soldiers witness Conan’s arrival on Xapur, and once he is out of sight they swarm over, ready to draw the noose tight. All the players are present and the stage is set.

The story careens along in a series of encounters which highlight the growing sense of unreality that now blankets the island. Conan, who was on Xapur just a month earlier for a clandestine meeting with a pirate crew, has come expecting an assignation. Instead, he is confronted by a city of greenish stone. “[S]omething was monstrously out of joint. Less than a month ago only broken ruins had showed among the trees. What human hands could rear such a mammoth pile as now met his eyes, in the few weeks which had elapsed?” Conan might have fled, then, had he not chanced to spot a piece of torn silk, still bearing Octavia’s intoxicating scent.

Fear is generally not a word in the lexicon of descriptors surrounding the Cimmerian. Indeed, Howard generally describes him as being remarkably fearless. But in “The Devil in Iron”, we’re presented with a picture of Conan who is nearly undone by the horror of the situation. Take, as an example, when he encounters the snake that graces the cover of this issue of Weird Tales. At first, he believes the sleeping monstrosity to be an eerie work of art, a statue. Then, he . . .

. . . laid a curious hand on the thing. And as he did so, his heart nearly stopped. An icy chill congealed the blood in his veins and lifted the short hair on his scalp. Under his hand there was not the smooth, brittle surface of glass or metal or stone, but the yielding, fibrous mass of a living thing. He felt cold, sluggish life flowing under his fingers.

His hand jerked back in instinctive repulsion. Sword shaking in his grasp, horror and revulsion and fear almost choking him, he backed away and down the glass steps with painful care, glaring in awful fascination at the grisly thing that slumbered on the copper throne. It did not move.

He reached the bronze door and tried it, with his heart in his teeth, sweating with fear that he should find himself locked in with that slimy horror.

We’re often told of the barbarian’s fear of the supernatural; here, we see it on full display – and not as a weakness, but rather as a show of good sense. Conan doesn’t want to fight the thing if he doesn’t have to. His focus is on finding Octavia and on getting the hell off this island.

Conan discovers the woman in Khosatral Khel’s clutches, where the latter’s long-winded villain speech is condensed into a dynamic flashback that reveals Khosatral’s long history, the particulars of his downfall, and the existence of the knife that is as the thumbprint of Thetis is to this indomitable proto-Achilles. The first encounter between Conan and Khosatral Khel goes as one might expect. The Cimmerian is faster, but his sword rebounds from the iron muscle of Khosatral’s belly; he shrugs off the impact of a heavy stone bench, only to be stymied by the entangling folds of a giant tapestry Conan casts over him.

Together, Conan and Octavia flee. They are very nearly trapped in a steel-walled room, its doors buckling under Khosatral Khel’s vicious onslaught, when something draws the devil away. Conan scoops Octavia up and makes a break for it. He remembers the knife, then, and goes to fetch it. This means slipping past the great snake that is its guardian. Conan tasks Octavia to watch for Khosatral Khel and warn him if he appears, then alone he slinks into the snake’s presence. The knife is behind a door, behind the dais on which the serpent rests. Howard tells us that “[a] wind blowing across the green floor would have made more noise than Conan,” who’d been a thief in his youth. He would have made it, I think, had Octavia stayed put. Instead, she barrels into the chamber, sees the snake, screams, and wakes the blasphemous creature. Conan may have been afraid of it, horrified by it, or repulsed by its slimy coils . . . but when the hammer meets the anvil the Cimmerian doesn’t hesitate to tangle with it.

It is not the most epic beast fight of the Conan canon, but it is suitably tense – and it heralds the end of the story as, fresh from his triumph over the forty-foot scaled terror, Conan makes a swift end of Jehungir Agha, alone after his troops were slaughtered by Khosatral Khel, and finally the titular devil in iron, himself.

“Conan, stooping above the body of the Agha, made no move to escape. Shifting his reddened scimitar to his left hand, he drew the great half-blade of the Yuetshi. Khosatral Khel was towering above him, his arms lifted like mauls, but as the blade caught the sheen of the sun, the giant gave back suddenly.”

The knife proves its worth. And Conan proves once again that the clean ferocity of the barbarian is more than a match for the creeping evil of the Abyss. He rams that ensorcelled blade into Khosatral Khel’s black heart, causing him to revert to his true form. “Conan, who had not shrunk from Khosatral living, recoiled blenching from Khosatral dead, for he had witnessed an awful transmutation; in his dying throes Khosatral Khel had become again the thing that had crawled up from the Abyss millenniums gone.” And with the demon’s passing, the green-walled city dissolves, becoming the vine-choked ruins Conan remembered from his last visit to Xapur.

The last bit of the story is spirited banter between Conan and Octavia – who have never actually met, if you recall, save for the smoky glances Jehungir forced her to send Conan’s way, and various bits of running and screaming since coming together on the island. And it ends with an exuberant Conan striding off, girl in arm, vowing to burn Jehungir Agha’s city of Khawarizm for a torch, so Octavia might find her way to his tent.

The final verdict? Robert E. Howard’s “The Devil in Iron” really isn’t the best of the Conan canon, but it echoes them. It hints at the fiery passions of “The Queen of the Black Coast”, and trades eastern mysticism for the raw realism of “Beyond the Black River”; Howard embraces his eerie and nightmarish side and runs with it, creating a solid bit of storytelling with a memorable villain, nods to the stories that make the spine of the Conan saga, and some deep lore of the Hyborian Age.

Note: All quotes are derived from the August 1934 edition of Weird Tales, via Project Gutenberg.

From the Dusty Scrolls (Editor comments)

Howard had taken a break from writing Conan stories in early 1933 (Weird Tales had a backlog already purchased – though not paid for) and didn’t return to the Cimmerian until October, with this story. He also wrote the first two El Bork tales around this time. So, we saw the influences of Harold Lamb (Conan) and Talbot Mundy (El Borak) on Howard’s writing that Fall.

In re-reading these tales more critically than I had in the past, I’m really seeing how weak most of the females are. Octavia is nothing but trouble on the island, nearly getting Conan crushed by the giant snake.

Conan had been part of Prince Almuric’s rebel army, which had been defeated in Koth, then “swept through the lands of Shem like a devastating sandstorm and drenched the outlands of Stygia with blood. With a Sygian host on its heels, it had cut its way through the black kingdom of Kush, only to be annihilated on teh edge of the southern desert.” That story has not yet been told as a pastiche: not in de Camp’s series, the Tor books, or by anyone else (don’t know about Dark Horse).

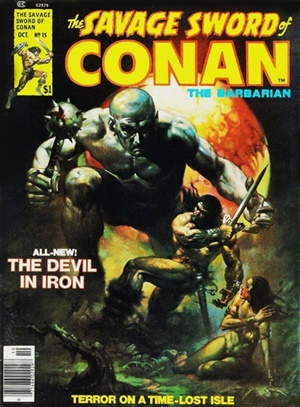

Dark Horse adapted this story for issues 7 – 12 of Conan – The Slayer. I have not read those issues. Marvel’s Savage Sword of Conan covered it in issue 15.

Prior Posts in the Series:

Here Comes Conan!

The Best Conan Story Written by REH Was…?

Bobby Derie on “The Phoenix in the Sword”

Fletcher Vredenburgh on “The Frost Giant’s Daughter”

Ruminations on “The Phoenix on the Sword”

Jason M Waltz on “The Tower of the Elephant”

John C. Hocking on “The Scarlet Citadel”

Morgan Holmes on “Iron Shadows in the Moon”

David C. Smith on “The Pool of the Black One”

Dave Hardy on “The Vale of Lost Women”

Bob Byrne on Dark Horse’s “Iron Shadows in the Moon”

Jason Durall on “Xuthal of the Dusk”

Next Week it’s James McGlothlin with “The Servants of Bit-Yakin/Jewels of Gwalhur

Scott Oden (author page here) was born in Indiana, but has spent most of his life shuffling between his home in rural North Alabama, a Hobbit hole in Middle-earth, and some sketchy tavern in the Hyborian Age. He is an avid reader of fantasy and ancient history, a collector of swords, and a player of tabletop role-playing games. When not writing . . . who are we kidding? He’s always writing.

Oden’s previous work includes the historical novels Men of Bronze and Memnon; the historical fantasies The Lion of Cairo and A Gathering of Ravens, and the ongoing pastiche Conan novella, “The Shadow of Vengeance”, serialized in Marvel’s The Savage Sword of Conan (2019).

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!).

He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

And he will be in the anthology of new Solar Pons stories coming this Spring.

Excellent, detailed essay.

For those curious about what Lamb’s influences were on this tale, I discussed some of those elements at length in the re-read Bill Ward and I did of this story over on my site, where we re-read and discussed each Conan yarn back in 2015.

Anyway, here’s the link to the discussion about this story:

http://www.howardandrewjones.com/sword-and-sorcery/the-coming-of-conan-re-read-the-devil-in-iron

And if you’re really curious, here’s a link to the entire series of re-reads Bill and I did:

http://www.howardandrewjones.com/category/conan-re-read/page/5

Also, while I’m flattered by the mention, I should say that I’m not entirely sure I’m a bonafide REH scholar, but more of a well-read fan. I think I’m definitely a Harold Lamb scholar, though. My master’s thesis is an analysis of his Cossack saga.

You’re an REH scholar in my book 🙂

Excellent!

Thank you, Mr. Oden.

Nice analysis of this story Scott, makes me want to read this one again soon. What this series has made pretty clear to me is that there is no truly bad Conan tale, at least from Howard’s pen. It’s just that the really good ones cast a shadow over the lesser adventures, resulting in dismissal by some readers and critics. But when reviewed on their own, without direct comparison to the top tier stories, they actually hold their own rather well. And within the genre of S&S, even lesser Howard is pretty damn good reading.

And in terms of being a Howard expert, you’re not to shabby yourself Mr. Oden!

The Devil in Iron is one of my favourites, definitely top three. Could be that I read it before a number of other stories which were as Scott has mentioned, re-used in this story, so to me the concepts seemed original. I think what I really liked about the story was the first section, detailing Khosatral’s ascent, how he came to clothe himself in iron and how the neanderthal like Yuetshi magician imprisoned him.

Correct me here, I work from memory, but we’re the inhabitants of the city not also redirected by Khostral being freed?

Love it. Thanks for the write up.

@Bob – I think Dark Horse did cover portions of Conans stint with Prince Almuric’s army.

From my reading of it, the city’s populace were resurrected by Khosatral Khel’s sorcery — along with the city itself. From Chapter 5: “It pleased him to restore the city as it was in the days before its fall. By his necromancy he lifted the towers from the dust of forgotten millenniums, and the folk which had been dust for ages moved in life again.

“But folk who have tasted death are only partly alive. In the dark corners of their souls and minds death still lurks unconquered. By night the people of Dagon moved and loved, hated and feasted, and remembered the fall of Dagon and their own slaughter only as a dim dream; they moved in an enchanted mist of illusion, feeling the strangeness of their existence but not inquiring the reasons therefor. With the coming of day they sank into deep sleep, to be roused again only by the coming of night, which is akin to death.” (Weird Tales, 1934 via Gutenberg).

Love it, another great article. being mostly new to thinking about the stories other then just having read them once a couple years ago, i find these as a great introduction to a more learned look at pulp.

also i wanted to chime in and say i am liking your novella in the back of the new Savage Sword comic Mr. Oden. thanks for it.

I’m late to the train on this one, having been away Monday, and then … not really sure I had anything to add. But then I decided I do.

“The Devil in Iron” is another of those middle Conan tales that for me don’t really rise above the pack. (Which is not to say there aren’t others that do.) But why? Basically because it’s another Lost Race Yarn, or at least an isolated odd place one, in a setting that not only doesn’t really need them, but is overloaded with them.

I have no problem with LRYs as such. I can see the attraction of such for escapist adventure from a mundane world. What is harder to justify is the need for it in a setting already exotic. Oh, it’s fine as an occasional thing to heighten the wonder or the horror. It’s when there are bushels of them that they become dime-a-dozen, like those denizens of the outer dark Conan expresses weariness with in “The Vale of Lost Women.” I mean, honestly, what need for a Xapur or a Xuthal or a Xuchotl or other X-marks-the-spot locale in the freaking Hyborian Age? Talk about gilding the lily! In such tales the malign specter of Haggard and Burroughs (and I suppose Lovecraft) looms large over Howard.

Well, at least it’s not one of those “Conan’s the last survivor of something that has nothing to do with this story and just happens to come across a lost city on its last legs” stories. Here, oddly enough, there’s less of a sense that the setting’s hastily erected just in time for his arrival for the VERY REASON that we SEE it hastily erected just in time for his arrival–and see, as well, that it has nothing to do with him. He’s just in the wrong place at the wrong time. Which is actually refreshing. If you have to do this sort of thing, this is definitely the way to do it.

The head-smacking contrivance this time lies elsewhere, for once, in the string-pulling that brings together the male and female leads–and helps halt this story short of excellence.

Overall, I think Scott does an great job here of highlighting both the best aspects of the story and its shortcomings. It’s a good job, and a good read, just not Howard’s best.

[…] to write the essays, instead of doing it myself! We’re just over halfway through the run. Here’s this week’s post, which includes links to all the prior ones. Make sure you check it […]

I just read the Savage Sword adaptation of the story, and two things stuck with me. The voice of Khosatral Khel is said to be a tolling bell, that detail is deliciously creepy. Also the priest who leads the Yuteshi tribesmen in revolt against Khel and the Dagonians in the dream, he doesn’t kill the giant, it is implied he could have but he doesn’t and is probably the last ruler of Xapur before the tribesmen turned on him I guess and it fell into ruins.

The Devil in Iron is a choppy story but Khsatral Khel really makes the story for me.