Books and Craft: Parables for the Modern Reader

|

|

|

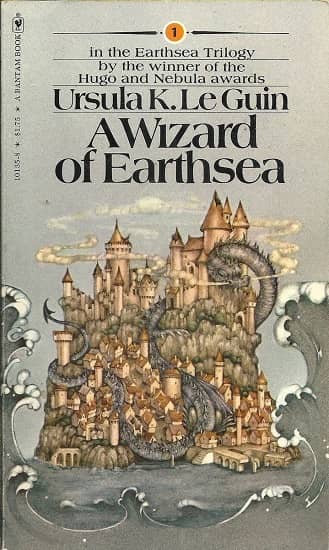

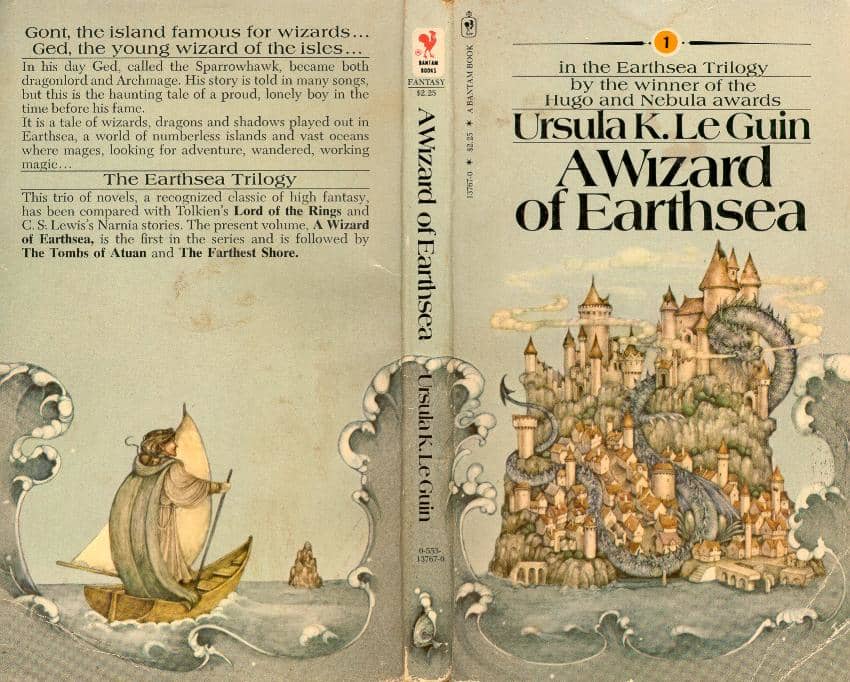

The Earthsea Trilogy (Bantam, 1975). Covers by Pauline Ellison

Early last year, I began a column here at Black Gate that I call “Books and Craft.” The idea was to shine a light on the writing elements that contribute to the greatness of classic works in our genre. (You might care to read my previous pieces on Nicola Griffith’s Slow River, and Guy Gavriel Kay’s Tigana .) I intended to write these on a regular basis, but life and work intervened. Today I’m happy to be back with a new “Books and Craft” post about books that have long been deeply special to me.

Ursula K. Le Guin died earlier this year after a stellar career of nearly sixty years. She was a master of speculative fiction, one of the most decorated writers ever to grace our genre. She was perhaps best known for her science fiction novels set in the Hainish Universe, but personally, I am most fond of her fantasy, specifically the first three of her Earthsea novels: A Wizard of Earthsea, The Tombs of Atuan, and The Farthest Shore. (In fact, my newest series, The Islevale Cycle, is set in a world of islands and seas that I meant as an homage to Earthsea and Le Guin.)

These three early Earthsea novels, often referred to as The Earthsea Trilogy, were published as children’s books. They were written, though, with a spare sophistication and elegance that appealed to a broad audience and brought them critical and commercial success. Earthsea is a world of myth, rich culture, and social complexity. By creating a network of islands and archipelagos, Le Guin ensured that her land would be home to a variety of traditions, customs, and people. And in making Ged, the hero of the series, dark-skinned, she brought a non-traditional protagonist to a genre that had, until that time, been overwhelmingly white.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

Still, to my mind, the things that make these books to effective are their narrative structure and voice. They are stories of adventure, with plenty of suspense and tension. But they are written as parables. There is a timeless quality to the narration, and a focus in the plotting on internal struggle and growth, that makes them read as morality plays. This may be because they were intended originally for a young audience. The result, though, is a series that transcends place and period and audience to speak to larger truths of humanity.

The three novels are coming of age stories, the first about Ged himself, the second about a girl named Arha, and the third about Arren a young prince. They all revolve around similar themes: the destructive power of pride; the acceptance of our own imperfections; and the quest for balance – between power and responsibility, between faith and dogma, between life and death. More, all three of our coming-of-age characters go through several phases of maturation, each with a different name and a corresponding unique identity.

|

|

|

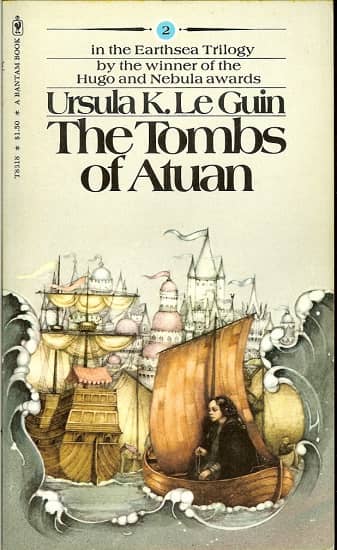

The Earthsea Trilogy (Bantam, 1986). Covers by Yvonne Gilbert

In A Wizard of Earthsea, our protagonist begins as Duny a young boy who shows signs of possessing power. As he explores his magical abilities in boyhood, he learns that he can call birds to his arm, and so is given the name Sparrowhawk by others his age. But Sparrowhawk is prone to conceit and ambition. Acting out of pride, he attempts a spell that is beyond his abilities and releases upon the land, and upon himself, a vicious shadow. He is wounded, scarred for life. Worse, with his pride shattered, and with the shadow pursuing him across Earthsea, he loses faith in his power. But he comes to realize that Ged, his true name, his name of power, is also the name of the shadow.

Ged spoke the shadow’s name and in the same moment the shadow spoke without lips or tongue, saying the same word: “Ged.” And the two voices were one voice.

Ged reached out his hands, dropping his staff, and took hold of his shadow, of the black self that reached out to him. Light and darkness met, and joined, and were one.

Thus Ged comes into his own as man and mage only when he accepts the dual nature of humanity, and of himself. He is shadow and man, evil and good, prideful and humbled.

The protagonist of The Tombs of Atuan goes through a similar transformation. Born Tenar, she is taken as a child by the priestesses of Atuan and ritually reborn as Ahra, the Eaten One, the reincarnation of the One Priestess of the Nameless Ones. And yet, she harbors within herself that earliest identity. The person to whom she is closest, her servant Manan, calls her “Little One,” a name she embraces, one that balances the darker names around her: “Eaten One,” “Nameless Ones.”

Ahra, too, succumbs to pride, embracing the dogmatic teachings of the priestesses that claim theirs is the only true power in Earthsea. When Ged comes to Atuan searching for an ancient magical talisman, Ahra traps him in the Tombs and resolves to let him die there. As she speaks with him, though, and learns more of his power and the world beyond her isle, she begins to question the teachings of her faith, and to long for a world separate from the evil Nameless powers she serves. Once she and Ged are free of Atuan, she becomes Tenar again, abandoning her ritual name for her truer self.

|

|

|

The Earthsea Trilogy (Saga, 2012). Covers by Dominic Harman

Finally, Arren, the Prince of Enlad, who is the protagonist of The Farthest Shore, seeks an audience with Ged, now Archmage of all Earthsea. Arren tells Ged that magic is vanishing from the world. Wizardry is dying, men and women of power have forgotten spells, and none seem to care. Together, they voyage across Earthsea seeking the cause of this calamity. They discover that a lone wizard is filling people’s heads with dreams of immortality. The balance between life and death is lost, and with it magic. Arren, though, is enticed by the notion of everlasting life. He loses faith in Ged and in wizardry, and convinces himself that a prince should be immortal, that this is true power, and the rest illusion.

Arren saw now what a fool he had been to entrust himself body and soul to this restless and secretive man, who let impulse move him and made no effort to control his life, nor even to save it. For now the fey mood was on him; and that, Arren thought, was because he dared not face his own failure – the failure of wizardry as a great power among men.

Only when Arren recognizes his own folly, does Ged take to calling him by his true name, Lebannen. They prevail in the end, but Ged’s magic is spent, and Arren must see the mage back to safety. It’s then we learn the young prince will take a new title and identity: King of Havnor, leader of all the isles of Earthsea.

|

|

The Islevale Series by D. B. Jackson (Angry Robot, 2018-19). Covers by Jan Weßbecher

The power of the structural and thematic components outlined here is reinforced by Le Guin’s prose. Balance is not only a recurring motif, it is also a stylistic choice. These novels are written with a rustic plainness suitable to fable, but also with the heroic loft common in fantasies of the 1960s and 1970s. Put another way, Le Guin’s prose is simultaneously lyrical and accessible. The books have the classic feel of mythology, but even at the time of their publication – a moment in our cultural and national history when too strict an adherence to old norms might have alienated young readership – they were seen as pertinent and meaningful.

Identity and balance, choice and responsibility, pride and humility, life and death – these are weighty concepts for children’s literature, in any period. The enduring strength of Le Guin’s work is its ability to convey these themes without condescension and also without oversimplification. The Earthsea books are modern parables: instructive, moving, engaging, readable, and perhaps more relevant today than ever before.

David B. Coe/D.B. Jackson is the award-winning author of twenty novels and as many short stories. As D.B. Jackson (DBJackson-Author.com), he is the author of The Islevale Cycle, a time travel/epic fantasy series from Angry Robot Books. The first book, Time’s Children, has just been released. He also writes the Thieftaker Chronicles, a historical urban fantasy set in pre-Revolutionary Boston. As David B. Coe (DavidBCoe.com), he is the author of the Crawford Award-winning LonTobyn Chronicle, as well as the critically acclaimed Winds of the Forelands quintet and Blood of the Southlands trilogy. Most recently he has completed The Case Files of Justis Fearsson, a contemporary urban fantasy. David’s work has been translated into a dozen languages.

David B. Coe/D.B. Jackson is the award-winning author of twenty novels and as many short stories. As D.B. Jackson (DBJackson-Author.com), he is the author of The Islevale Cycle, a time travel/epic fantasy series from Angry Robot Books. The first book, Time’s Children, has just been released. He also writes the Thieftaker Chronicles, a historical urban fantasy set in pre-Revolutionary Boston. As David B. Coe (DavidBCoe.com), he is the author of the Crawford Award-winning LonTobyn Chronicle, as well as the critically acclaimed Winds of the Forelands quintet and Blood of the Southlands trilogy. Most recently he has completed The Case Files of Justis Fearsson, a contemporary urban fantasy. David’s work has been translated into a dozen languages.

I wonder if the very simplicity of the original trilogy – like you say, the books are essentially parables – is one reason why I feel Tehanu suffers by comparison?

Could be, Aonghus. To be honest, I have yet to read TEHANU. That original trilogy is so dear to me, I was somewhat reluctant. Now I’m interested to check it out.

My memory is that Le Guin got a certain amount of flak for writing stories in which the truly powerful wielders of magic were all male (ie, wizards) with women being relegated to the lesser role of Hedge Witch. Tehanu tries to address this – a commendable undertaking, but I think the end-result lacks a certain oomph. It’s also tonally very different from the previous three books, which are very much products of their time (ie, the Sixties and early Seventies*) – and I mean that in a good way.

But then (a) I’m a man & (b) I didn’t actually finish ‘Tehanu’. So what do I know?

* ‘Tehanu’ came out in 1990

I love the Ellison covers (I think those were the ones I read originally, unless I was actually getting hardcovers from the school library). I like the Gilbert covers as well. Not as much of a fan of the Harman covers, although I suspect they work better these days when people are browsing Amazon, etc.

Aonghus, if you read interviews with Le Guin, she was actually pretty hard on herself for making magic as gender imbalanced as she did. It was one reason she gave for taking so long to return to that world.

Joe, I agree — I LOVE the Ellison covers. Not nearly as fond of the later versions, though there was an edition that used the Vess drawings. I think you can find them if you look on Google images.

There’s going to be a big, Vess-illustrated hardcover omnibus of all six books that I think is going to have to come home and live with me when it’s released.

I was initially ambivalent about Tehanu, but at a decade’s remove from reading it and The Other Wind, I’ve come to feel like the late books bring a lot more to the series than just a corrective to an early flaw in the worldbuilding. What Le Guin does with the dragons, the grim afterlife we saw in The Farthest Shore, the menacing Old Powers we saw in the northern movement in A Wizard of Earthsea and the Kargish religion Tenar was raised in — all those things are actually way more important to the page-by-page experience of the story. And finally, as they approach old age, Ged and Tenar get to talk frankly about the way, in the end of The Tombs of Atuan, they missed an opportunity to make a life together. There’s a lot of cool stuff in those novels, and some lovely bits in the Earthsea short story volume, too. If you’re on the fence about reading those books, I think you won’t regret giving them a chance.

Thank you for that, Sarah. I do love her world and her writing. So why wouldn’t I give them a shot. The perfect excuse for buying the new illustrated collection!