Only the Monsters Can Save Us: Claude Debussy meets Godzilla

Nothing can be more exhausting, enervating, overlong, and less worthy of repeat viewings, than a Hollywood summer blockbuster, but these supermovies are often preceded by invigorating trailers that deliver all their best features in a small fraction of the running time. This has never been truer than it is for the new (July 2018) trailer for next year’s Godzilla, King of the Monsters.

Music is the reactor core that powers this remarkable two and a half minutes of commercial cinema salesmanship. The nineteenth century composer Claude Debussy meets the 21st-century kaijū movie in a work noteworthy for both (1) its profoundly affective qualities and (2) the extent to which, as promotion for a Hollywood blockbuster, it’s strictly business. Let’s begin with the affective part.

A world in flames. A military in disarray. A divided family: to the Vera Farmiga character’s husband, she’s “out of her goddamned mind,” and her daughter calls her “a monster.” These are all familiar tropes from the movies, but not from the classic Godzilla movies, where typically the everyday world is more or less functional and well-organized; a world where the monsters enter as a destructive and destabilizing force.

I use “classic” to loosely describe the period from Godzilla’s 1954 debut to the 1970s, where Godzilla‘s onscreen persona evolved from the sheer vengeful malignity of the original Gojira, to a villain set up to be defeated by other, nice monsters, to a more or less sympathetic antihero, in movies in which he came to embody either the benign indifference of the universe, or a friendly giant who would be a welcome guest on a morning kid’s show (if he could avoid crushing the TV studio under his enormous feet).

Long live the king: the use of Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” in the new Godzilla

trailer brings the franchise into a more Europeanized world of music,

melodrama and myth. Charles Dance, Millie Bobby Brown, Vera Farmiga.

Once the tone of the trailer is established – “our world is changing,” narrates Farmiga’s character, “the mass extinction we feared has already begun” – a broken chord introduces, rather than the expected dark, suspenseful Hollywood music, the first bars of Claude Debussy’s “Clair de Lune.” The contemplative, almost rubato piano gives a touch of unexpected whimsicality to the introduction: emotionally, just where are we going here? Then we cut to the monsters – no, not obsessed mothers, real monsters: Godzilla’s fellow Toho creatures Mothra, Rodan, and the three-headed Ghidrah. This has all been anticipated by Godzilla-watchers – in fact, it’s been formally announced by Warner Brothers – since Gareth Edwards’ 2014 Godzilla brought the long-lasting Japanese franchise into the world of the $100 million-plus Hollywood blockbuster.

No one, however, expected this music. A backdrop of strings and voices has risen behind the familiar solo piano of the Debussy piece. There is a pause, and Godzilla makes one of his familiar entrances, rearing up slowly and ominously from a stormy sea, his dorsal plates shedding seawater, accompanied by an electronic effect that sounds like the revving of some immense prehistoric engine. Then a surprise: “Clair de Lune” returns, now orchestrated for orchestra and choir. If film music tells us what to feel in relation to the images, the swell of the music tells us, as Mothra, then Rodan, then Ghidrah appears, that these are creatures of cosmic importance, and that their emergence is a good thing. Apocalypse is still the order of the day – but an apocalypse that, if we’re lucky, will lead to better things.

“Clair de Lune,” the third and most famous movement of Debussy’s Suite bergamasque, is based on a poem by Debussy’s contemporary Paul Verlaine. The poem is readily available online; I’ve done a quick Google translation, and then subjectively amended it in places where Google clearly fell short:

Clair de Lune (Moonlight)

Your soul is a chosen landscape

Of charming masks and bergamasques

Playing the lute and dancing and almost

Sad under their playful disguises.

While singing in the minor mode

Of victory in love and life

They do not seem to believe in their happiness

And their song mixes with the moonlight,

The calm moonlight, sad and beautiful,

That makes the birds in the trees dream

And ecstatically sob fountains of water,

Great, slender fountains of water among the marbles.

The poem describes an essentially unchanging night world of enduring sadness, one where life processes are tied in with the cosmic forces of the moon and moonlight; when the moon shines, the birds dream sad dreams, and sob great fountains of water.

The trailer is structured so that its dramatic effects build along with the music. From the simplicity of the original solo piano, the arrangement by Russian composer Michael Afanasyev builds to Wagnerian density: though we’re not yet sure what’s going on, the music tells us it’s important. Even non-Godzilla fans are bound to be affected.

The music is also on several levels an act of appropriation. Otherwise, why use such a familiar piece instead of creating an original composition? One reason is that “Clair de Lune,” already familiar to many musicians and listeners, it is the work of a French composer, orchestrated in the classic Romantic manner. Solo piano, building to a climax with strings, percussion and choir: this is the apotheosis of how we think of Great Art in the Western world. The music is telling us among other things, that the story of Godzilla is no longer Asian, no longer Japanese. No more Akira Ifukube or Masaru Sato, with their unique takes on rhythm and melody, and their surprising uses of western instruments and orchestration. The music places Godzilla, King of the Monsters firmly within the Hollywood tradition of film scoring, and in doing so re-historicizes the Godzilla franchise as part of a Western, rather than Eastern, cultural lineage. To make sure that they follow the successful formulas of other blockbusters, the producers of Godzilla, King of the Monsters need to appropriate the franchise into the Euro-American-centered colonial sphere that has already proven so successful for other franchises, from Mission Impossible to Fast and Furious to the Marvel universe. Grand orchestral music in the classical tradition does that for them.

“Sheer, vengeful malignity”: Gojira/ Godzilla, King of the Monsters, 1954. The title is

an example of how the moment’s contingency becomes future canonization: in 1954,

its American distributors appended “king of the monsters” onto the title Godzilla

so that audiences would have some idea of what this strange Japanese film was about;

now kinghood is part of the character’s persona: “Love live the king,” sneers

Charles Dance in the new trailer

In some ways, this could be a good thing. If, like me, you saw the original Godzilla at the age of six or so, you were entranced by its ambience of sheer tragedy. After its nightmarish black & white scenario of innocent victims turned to ash, its echoes of the 1945 atomic attacks, the doomed love triangle at the heart of its plot – not to mention the flesh-sucking horror of the oxygen destroyer – every subsequent film, with its outlandish monsters, inane sub-plots, and bad jokes, was in some way a disappointment. To us, Godzilla was as serious as King Lear or Mildred Pierce. Big as Godzilla is, we knew he was an allegory for power, problems, and principles that were even bigger.

Edwards no doubt felt the same way when he made the 2014 Godzilla, though the results, rather than sad, dark, and tragic, tended to be grey, grim, and unmoving (you know the filmmakers have missed the mark when they have San Franciscans cheering for a monster that has just helped level their city, torn apart the Golden Gate Bridge, and killed thousands of citizens). Godzilla as a Hollywood product, however, might not be an altogether bad thing if it means that Godzilla will never again dance a jig, befriend little boys, or talk out his feelings with his fellow monsters. Can the childish pleasures of watching stunt actors in outlandish suits trampling balsa-wood buildings and throwing foam boulders at each other be transmuted into high-stakes, world-saving melodrama without making an adult audience burst out laughing?

A Hollywood Godzilla means, on the other hand, the end of Godzilla films as a subversive art form. Since the 1950s, they were one of the few franchises that managed to come from overseas and win wide distribution through North American cinemas (Hammer horror films were another). If you were a kid going to your small-town cinema in 1964, there was a kind of hipness in choosing to see Godzilla vs. the Thing with its outrageous sense of scale, its exuberant colour scheme, and its wacky imagination, instead of the latest Hollywood musical, World War II epic, or Elvis vehicle. American pop culture ruled the world, but a Godzilla movie gave you a glimpse into an alternate world.

|

|

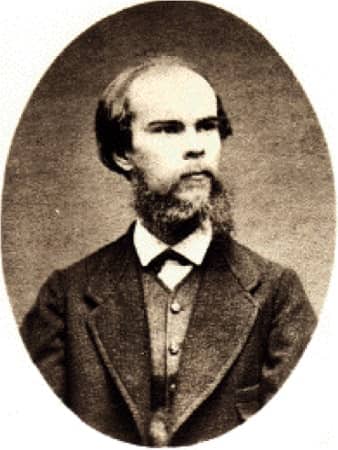

Paul Verlaine / Claude Debussy

Nevertheless the trailer, and its use of music, are still remarkably effective. As a solo piano piece, Clair de Lune is a haunting work, and when it is orchestrated as it is here with strings, percussion, and choir, it’s irresistibly moving (note: all these “orchestral” sounds, including the voices, are probably synthesized). The Farmiga character tells us that these monsters are, in some way, “the only guarantee that life will carry on.” Without the music, this sounds like the sort of intriguing premise that the Edwards Godzilla tried, but failed to carry out. A standard Hollywood orchestral score, with its roaring legati, horn stings, and cymbal crashes, might have made it more convincing. But the use of Clair de Lune, in this particular arrangement, effectively places the music in an imaginative landscape of unending dances, of empty pleasures, in a world where the birds in the trees dream in the moonlight and sob fountains of pure water.

The music tells us that the monsters embody nature itself, and that nature is more powerful than the human instinct to pillage, to waste, to consume without nurturing – the human need to take, and take, and take, and never give. In this, as in all our myths and legends, monsters are frightening and destructive – but monsters also embody the necessary impossible. The very existence of monsters implies a different ecology, a different cosmology. If such a creature as Godzilla existed – or Dracula, the Alien xenomorphs, werewolves, the Frankenstein monster, or the Hulk – then it would mean that there are powers at work that none of our logic and technology can circumvent; powers that, should we manage to survive them, might even be there for our own good.

The monsters force a paradigm shift that we will need in order to understand our present position, and then move on from it. The music opens a doorway into a world where the bizarre pataphysics, biology, and history of these creatures can surface; the music tells us (and in these dark times, it might well be true) that only the monsters can save us.

Postscript: There are lots of worthwhile versions of “Clair de Lune” online, including a piano roll recording supposedly made by Debussy himself, and a terrific version arranged for guitar by James Edwards, played by Roxane Elfasci. Thanks to Dr. James Deaville of Carleton University for drawing my attention to this work.

David Neil Lee’s Lovecraftian YA novel The Midnight Games won the Hamilton Arts Council’s 2015 Kerry Schooley Award for the book that “best conveys the spirit of Hamilton.” He has recently completed the first draft of a sequel, The Medusa Deep, projected to be published in 2019. davidneillee.com

The first thing a mature moviegoer learns: a great trailer does not necessarily mean a great movie.

So…when was the last time I was suckered by a trailer? Ummm…what day is it?