Fantasia, Day 11, Part 2: Wilderness Parts One and Two, and Parallel

I like to make out a rough schedule for Fantasia well ahead of time. But things always change. You hear things about movies as the festival goes on. What seems important a few days out seems less important in the moment. And then some choices are just hard to make. On Sunday July 22 I had one of those tough choices, which I’ll walk through here for the sake of recreating a bit of the subjective experience of Fantasia.

I like to make out a rough schedule for Fantasia well ahead of time. But things always change. You hear things about movies as the festival goes on. What seems important a few days out seems less important in the moment. And then some choices are just hard to make. On Sunday July 22 I had one of those tough choices, which I’ll walk through here for the sake of recreating a bit of the subjective experience of Fantasia.

The Hall Theatre would host Our House, a science-fictional horror film, at 4:45. Then The Witch: Part 1. The Subversion, an action-superhero film, at 6:45; then I Am A Hero, a Japanese zombie film, at 9:15. On the other hand, starting at 4:20, the J.A. De Sève would host a five-hour-plus screening of a near-future boxing story called Wilderness, a two-film series playing here back-to-back with a brief intermission between the two parts. That would be followed by a science-fictional suspense film called Parallel at 9:45.

I was initially planning to stick with the movies at the Hall. Then I began to reconsider. The Witch and Hero had second screenings. Parallel did not. That meant it made more sense to watch that one, and catch Hero on its second screening on the 23rd. Witch had a question-and-answer session afterward, which I wouldn’t get at the second screening. But I found myself intensely curious about Wilderness. It was a bold programming choice to schedule a five-hour block. And I wondered how its setting would inform its story; it was adapted from a novel written and set in the 1960s. I decided at the last minute to choose Wilderness over Our House. I missed what I later learned was a touching question-and-answer session, where the lead of The Witch was surprised with the festival’s award for Best Actress. But in terms of the movies I ended up seeing, I was quite pleased.

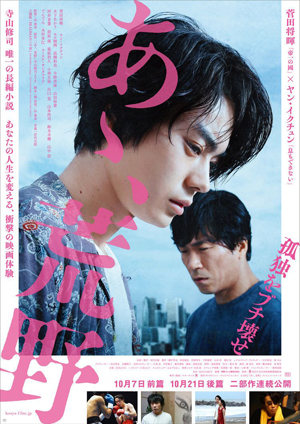

Wilderness (Ah, kôya, あゝ、荒野) was directed by Yoshiyuki Kishi and written by Takehiko Minato based on the novel by Shuji Terayama. Terayama’s Ah, kôya was published as a serial in 1965, and in one volume the year after; the film’s set in 2021, imagining a near future filled with social unrest. As the government mulls over legislation imposing a kind of conscription on Japan’s youth, and the numbers of suicides spike upward, two different men are drawn to take up boxing. One, Shinji (Masaki Suda, who voiced the lead in Fireworks and appeared in Gintama, Death Note: Light Up the New World, and the Assassination Classroom movies), is looking for revenge on a former friend, Yuji, who himself has taken up boxing. The other, the introverted stuttering Kenji (Ik-joon Yang), finds boxing is simply something he can do, something in which he can take confidence, something that might help him stand up to his abusive father. Both men are trained by gym owner Horiguchi (Yûsuke Santamaria, the voice of Hideo in Giovanni’s Island) as they learn how to box and go pro. A subplot sees a group of college activists planing an art project about the rise of suicides across the country.

The movie (and I do think of it as one movie in two parts) follows Shinji and Kenji’s careers, but is mainly about their relationship; as well as their relationship with Horiguchi, Kenji’s relationship with his father, and Shinji’s relationship with his prostitute-thief girlfriend Yoshiko (Akari Kinoshita). There’s an overall feel of intense realism, the camera always handheld, almost always focussed on the characters. The acting’s superlative, Suda and Yang especially. Shinji’s manic energy and Kenji’s awkward shyness are both clear and memorable without feeling exaggerated or broad. As the movie goes on they develop as characters while also gaining in symbolic freight. Shinji fights because of hatred, fights because of the hatred and rage inside him, and believes that you have to hate to fight well. Kenji finds himself fighting as a way of connecting with others. It’s a movie in many ways about the search for connection with others among the urban wild, and the story’s convincing in making boxing the central metaphor. In the second part of the film some of the connections among the characters feel a bit forced, melodramatic or even soap-operatic, even if the thematic point of these story choices is clear; but the drama still lands, the characters still maintain a core of reality.

The movie (and I do think of it as one movie in two parts) follows Shinji and Kenji’s careers, but is mainly about their relationship; as well as their relationship with Horiguchi, Kenji’s relationship with his father, and Shinji’s relationship with his prostitute-thief girlfriend Yoshiko (Akari Kinoshita). There’s an overall feel of intense realism, the camera always handheld, almost always focussed on the characters. The acting’s superlative, Suda and Yang especially. Shinji’s manic energy and Kenji’s awkward shyness are both clear and memorable without feeling exaggerated or broad. As the movie goes on they develop as characters while also gaining in symbolic freight. Shinji fights because of hatred, fights because of the hatred and rage inside him, and believes that you have to hate to fight well. Kenji finds himself fighting as a way of connecting with others. It’s a movie in many ways about the search for connection with others among the urban wild, and the story’s convincing in making boxing the central metaphor. In the second part of the film some of the connections among the characters feel a bit forced, melodramatic or even soap-operatic, even if the thematic point of these story choices is clear; but the drama still lands, the characters still maintain a core of reality.

Structurally both parts are solid, and the divide is well-chosen. The first part has a definite ending but is still clearly only a part of the story. It’s unusual for Fantasia to schedule two films together in a five-hour block, but I can see why they did it here. Both separately are long for single movies, and the first part cries out for a second. The second, on the other hand, doesn’t provide much in the way of recap; you’re dropped into the ongoing story. It must have been a difficult programming decision, but it works. I’m convinced this was the ideal way to experience this work.

The movie literally begins with a bang, as an explosion goes off in the middle of a city; we’re introduced to Shinji as crowds flee and he, unconcerned, orders noodles at a fast-food place. He’s not involved with society, but the 2021 backdrop impinges on the film in many ways — as here, where we learn key aspects of a character at once, in a contrast with the world around him. Through news stories in the background and bits of throwaway dialogue the sense of a society about to boil over keeps growing, ultimately escalating to a climax in parallel with the inevitable final duel we get in a boxing ring. But as with so much in this film, we learn about the world of 2021 in many different ways and from many different angles. Crucially, it shapes the subplot with the college kids, which in turn powerfully feeds back into the main storyline. Nothing’s isolated here.

The movie literally begins with a bang, as an explosion goes off in the middle of a city; we’re introduced to Shinji as crowds flee and he, unconcerned, orders noodles at a fast-food place. He’s not involved with society, but the 2021 backdrop impinges on the film in many ways — as here, where we learn key aspects of a character at once, in a contrast with the world around him. Through news stories in the background and bits of throwaway dialogue the sense of a society about to boil over keeps growing, ultimately escalating to a climax in parallel with the inevitable final duel we get in a boxing ring. But as with so much in this film, we learn about the world of 2021 in many different ways and from many different angles. Crucially, it shapes the subplot with the college kids, which in turn powerfully feeds back into the main storyline. Nothing’s isolated here.

The college kids also provide a different class background on the world. The boxers live in the margins of the film’s urban setting, with marginal jobs and marginal homes and marginal prospects. That’s evoked well and credibly. Class isn’t spoken of much as such, but subtextually it’s huge, defining what characters do and why — how different characters think about money, how minor characters react to boxing matches, what success means.

It’s part of a function of how polyvalent the characters are: we see different facets of them in the light of their different relationships with different people. And they relate differently to different people, which sounds simple but is difficult to pull off. More, their different ways of interacting with each other changes as the relationships change over the course of the story. These dynamics make up the movie and in that way this is really a character-centred drama.

At the same time, it’s also an unconventional martial-arts film. The boxing matches are shot well and acted well; you feel the weight of the blows, the pain of the characters, the damage they take even in a win. The narrative avoids many of the usual structures of the martial-arts film, although not all of them; Shinji wants to get revenge on Yuji because Yuji crippled Shinji’s old mentor, for example. But it mainly relates to other martial-arts films, I think, in the way it emphasises the personal discipline boxing gives Shinji and Kenji — the sense that boxing builds character. That in turn seems to relate to the aimlessness of youth, and the laws being proposed to conscript youth into social service. But it also relates to the title of the movie: discipline against the wilderness within.

At the same time, it’s also an unconventional martial-arts film. The boxing matches are shot well and acted well; you feel the weight of the blows, the pain of the characters, the damage they take even in a win. The narrative avoids many of the usual structures of the martial-arts film, although not all of them; Shinji wants to get revenge on Yuji because Yuji crippled Shinji’s old mentor, for example. But it mainly relates to other martial-arts films, I think, in the way it emphasises the personal discipline boxing gives Shinji and Kenji — the sense that boxing builds character. That in turn seems to relate to the aimlessness of youth, and the laws being proposed to conscript youth into social service. But it also relates to the title of the movie: discipline against the wilderness within.

The movie’s very restrained with the symbolism its title implies. Nearly all of the two-part story takes place in the city, except a couple of brief journeys to the seaside (where we see, perhaps, how impossible it is to get away from one’s past) and a crucial climactic image of a calm nature. Conversely, some of the characters have a past linked with the Fukushima disaster: a natural calamity that spawned environmental catastrophe. The actual wild is fragile, shaped by human action. The city is the wilderness, in other words, and a wild generation grows within it. We don’t get many gleaming views of skyscrapers here, except as Shinji and Kenji run past them as they train. Their gym opens off the street, onto a vacant lot. Their matches all seem to take place in the same ring.

I have not read Shuji Terayama’s novel (I’m not sure it’s been translated into English). But the film strikes me as having been very successfully adapted into the near future. The characters feel like people of the present day. There’s perhaps less social media use than one might expect, but it’s there, particularly from the college kids. I will note that one of the more saintly characters develops homoerotic feelings and dies before they’re clearly consummated; in this the movies seems to traffic in an unfortunate trope. Otherwise it’s a powerful film. It uses boxing as a way to get at big questions about life, viscerally if not cerebrally. Strong characters make for strong drama, and that is what this is.

I have not read Shuji Terayama’s novel (I’m not sure it’s been translated into English). But the film strikes me as having been very successfully adapted into the near future. The characters feel like people of the present day. There’s perhaps less social media use than one might expect, but it’s there, particularly from the college kids. I will note that one of the more saintly characters develops homoerotic feelings and dies before they’re clearly consummated; in this the movies seems to traffic in an unfortunate trope. Otherwise it’s a powerful film. It uses boxing as a way to get at big questions about life, viscerally if not cerebrally. Strong characters make for strong drama, and that is what this is.

The next feature was Parallel, but playing before it was a short film called “Space/Time Conundrum,” written and directed by Fernando Lopez. A time traveller (Danny Bass) stumbles into a diner and demands to know what year it is. But has he been there before? What is the curiously jaded woman at the cash (Shelby Brunn) hiding? This is a short story that’s deeply affecting in a way that has nothing to do with time travel. It builds well and quickly to a solid twist that ties off the film very neatly but very powerfully — it both explains the plot thoroughly, recontextualises everything we’ve just seen, and seems to open up a new emotional world. It’s a very neat trick, but more than a trick because it retroactively makes the story much more heartfelt than we’d understood at one viewing.

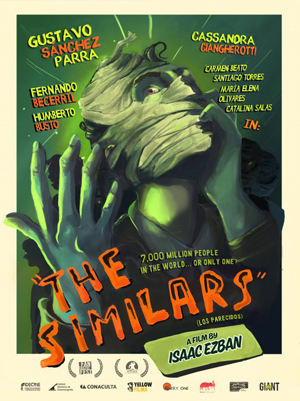

Parallel came next. Directed by Issac Ezban and written by Scott Blaszak, it follows a group of four friends who’ve founded a tech startup. Noel (Martin Wallström), Carmen (Alyssa Diaz), Josh (Marc O’Brien) and Devin (Aml Ameen) have rented a house as they pitch their new app. It turns out a former owner of the house left a secret room, and in the room a magic mirror — a device that opens doors into other realities. The realities aren’t too far off this one, all of them have a different version of the house, but all have slightly and randomly divergent pasts. Shifting the mirror on its axis gives a new dimension, literally at a different angle to reality. The young capitalists eagerly exploit the machine to make money. At first they use a time-dilation side effect — time passes more quickly in the alternate realities than the normal world — to get a lot of work done in little time. Then they begin plundering other realities for their intellectual properties — inventions and works of art. But each of the four soon finds themselves drawn by a different temptation. Conflict breaks out. And, perhaps inevitably, murder.

Parallel builds very nicely as the film goes along, as new implications are teased out of what the mirror can do. It’s extremely well-shot, using visual cues to differentiate between the alternate worlds and the normal world, and always unobtrusively finding solid angles from which to present the action. This lets the movie go through a series of twists while always remaining clear. I’d argue that the very final twist in the last seconds is unneeded, but this is perhaps a matter of taste.

Parallel builds very nicely as the film goes along, as new implications are teased out of what the mirror can do. It’s extremely well-shot, using visual cues to differentiate between the alternate worlds and the normal world, and always unobtrusively finding solid angles from which to present the action. This lets the movie go through a series of twists while always remaining clear. I’d argue that the very final twist in the last seconds is unneeded, but this is perhaps a matter of taste.

In general this is a smart movie that maintains a good pace, equally well-adapted to comedy and to a thriller. It’s genuinely unpredictable, I found, although relentlessly logical. I did think that the later part of the film felt a little small-scale, after the characters had greatly enriched themselves by using the device. But then again, they were keeping the device secret and so had every incentive to keep the number of people around them low.

In any event, the film makes a series of clever moves. It sets up a group of unsympathetic protagonists and then introduces a device that allows them to indulge their worst instincts without consequence. Remarkably, it still largely succeeds in getting them to slowly grow on us, at least to the point where we care about what happens to them. These four lust for success, however defined; as Noel asks rhetorically, in a now-ironic line, “would Elon Musk let a little bit of failure get him down?” Noel’s determined to be rich, and thanks to the device, he can realise that dream. Carmen can become a great artist by plagiarising the art of alternate realities. Josh can use the device to start relationships with a range of women and never follow through. Devin, at least at first the most sympathetic of the four, wants to have a last conversation with his father, dead in this reality — and, as he finds, in most of the alternates.

So the four of them face their different temptations. It’s a Faustian story for an age of VCs and NDAs and hypercapitalism, in which one of the great discoveries of human history is only an advantage to be exploited for monetary success. The lack of idealism of the characters is engagingly honest: they don’t even pretend to have ideals. And as a group they reinforce each others’ worst impulses. The dynamic’s well-observed. The way they approach the machine tells us who they are. And they things they all seek tell us more. The device acts to reveal character. The movie’s a solid genre piece in that sense, character and plot indistinguishable from the genre element. The device pushes them, just by existing, drives them further along the path each was already on. It’s quite credible that these people are friends, in that they share a similar worldview, and it’s quite credible that they can each take the actions against each other that they do, in that their attachments aren’t necessarily that profound.

So the four of them face their different temptations. It’s a Faustian story for an age of VCs and NDAs and hypercapitalism, in which one of the great discoveries of human history is only an advantage to be exploited for monetary success. The lack of idealism of the characters is engagingly honest: they don’t even pretend to have ideals. And as a group they reinforce each others’ worst impulses. The dynamic’s well-observed. The way they approach the machine tells us who they are. And they things they all seek tell us more. The device acts to reveal character. The movie’s a solid genre piece in that sense, character and plot indistinguishable from the genre element. The device pushes them, just by existing, drives them further along the path each was already on. It’s quite credible that these people are friends, in that they share a similar worldview, and it’s quite credible that they can each take the actions against each other that they do, in that their attachments aren’t necessarily that profound.

Worth noting also that the wit here isn’t restricted to the plot. this is a funny movie. There are some good lines — one character’s told he’s ruined another man’s life and argues “His life was already ruined! He was a software engineer!” — and they’re delivered well, but the point is that they’re lines that feel in character. Often cruel, they emphasise the amorality of the characters. There’s a strong streak of social satire in this film, and the gags further it on one level while the choices made by the characters drive it on another.

Eventually the humour recedes, as the dark choices pile up. The film makes a very nice pivot from one tone to another, as suspense aspects begin to take over. The device becomes a locus of paranoia in many ways, and romantic tensions always implicit in the group reach the surface. Still, the romance angle feels almost incidental: even without that element it’s clear that this is not a situation that can remain in equilibrium.

Parallel is a remarkably tight movie. Every set-up pays off, every character has a purpose, and every relationship among the characters serves to advance the overall plot. This actually has a downside — there’s not much left for implication. It’s not that there’s no subtext, so much as that the characters are by necessity so shallow there’s a limit to how much subtext any of them really can have. That is, the film’s a deep depiction of shallow people. That’s fine as far as it goes, and points up the satirical aspect of the movie. If the film were any less assured, though, it would feel as though it were missing a beat, skipping too lightly over the central wonder of the world-travelling device.

Parallel is a remarkably tight movie. Every set-up pays off, every character has a purpose, and every relationship among the characters serves to advance the overall plot. This actually has a downside — there’s not much left for implication. It’s not that there’s no subtext, so much as that the characters are by necessity so shallow there’s a limit to how much subtext any of them really can have. That is, the film’s a deep depiction of shallow people. That’s fine as far as it goes, and points up the satirical aspect of the movie. If the film were any less assured, though, it would feel as though it were missing a beat, skipping too lightly over the central wonder of the world-travelling device.

But in fact it is that assured, and feels like just the movie it wants to be. It’s not profound in the fullest sense, I suppose, but it’s a solid genre tale that does just what it wants to do. There’s a high level of craft involved in this film, at every level.

After the screening, director Isaac Ezban and writer Scott Blaszak came out to take questions along with producer John Zaorzirny (my write-up, which follows, is as always based on my handwritten notes). The first question, to Ezban, was how Parallel fit in with his previous films, The Incident and The Similars. Ezban (who, incidentally, has agreed to direct an adaptation of Dan Simmons’ Summer of Night) observed they were both science-fiction, and like Parallel were love-letters to The Twilight Zone. He said he liked the human aspect of SF, and that he wanted people walking out of a theatre playing one of his films to talk about it for days. He said he read many SF/horror scripts, and liked Parallel for its network of characters and individual relationships, as well as its sense of fun. He also liked the process of finding out how the machine worked, and the way the film became horror in its second half — Ezban noted he likes movies that become different movies in their second halves. He said Parallel reminded him of movies he saw growing up, in which characters played with the fire of the gods and learned that ambition can destroy you. He mentioned a number of films that he felt influenced Parallel, including Flatliners, Primer, and Chronicle, suggesting that the overall feel of his movie was Flatliners meets The Social Network.

Blaszak was asked how he found the original twist for this story; he answered that he read an article about young people who travelled to Europe on a gap year before graduate school and reinvented themselves, and that led him to imagine travelling somewhere there really were no consequences — who would kill someone, for example? He built out from there. Ezban then answered a question about the film’s colour palette by saying he was a fan of classic films and doing things practically where possible, citing De Palma and Hitchcock in particular. He liked using lots of information and dialogue in his films, and finding ways to shoot that dialogue which were not typical. He praised his director of photography, Karim Hussein (whose Rupture I quite liked two years ago), and said that Hussein taught him a lot about film and story. He noted that the film is fast, and said they wanted to make sure people wouldn’t get confused about what reality the characters are in at any given moment; they used spherical lenses for the normal world and anamorphic lenses for the alternates, creating a distinctive look. Similarly, the camera was usually still in the normal world and moved much more in the alts. The colour palette was also different, amber in the normal world and desaturated and blue in the alts. Ezban also observed the rules broke down as the film went on and the realities grew more mixed.

Blaszak was asked how he found the original twist for this story; he answered that he read an article about young people who travelled to Europe on a gap year before graduate school and reinvented themselves, and that led him to imagine travelling somewhere there really were no consequences — who would kill someone, for example? He built out from there. Ezban then answered a question about the film’s colour palette by saying he was a fan of classic films and doing things practically where possible, citing De Palma and Hitchcock in particular. He liked using lots of information and dialogue in his films, and finding ways to shoot that dialogue which were not typical. He praised his director of photography, Karim Hussein (whose Rupture I quite liked two years ago), and said that Hussein taught him a lot about film and story. He noted that the film is fast, and said they wanted to make sure people wouldn’t get confused about what reality the characters are in at any given moment; they used spherical lenses for the normal world and anamorphic lenses for the alternates, creating a distinctive look. Similarly, the camera was usually still in the normal world and moved much more in the alts. The colour palette was also different, amber in the normal world and desaturated and blue in the alts. Ezban also observed the rules broke down as the film went on and the realities grew more mixed.

Asked how he managed to provide information to the audience, Blaszak said it was a big challenge, but also said he found it was possible to cut exposition that was unneeded because the audience already understood a certain cinematic shorthand. He mentioned one passage that used to be five lines and became one line when it was obvious the rest was unneeded. He said he likes rewriting, going over and over his material, and also likes cutting ideas he finds he doesn’t need. Ezban was asked about a scene in which characters blow up a pile of money, and Ezban observed that this was a case where limitations made a scene more creative. They’d originally planned the scene to have the characters crashing two sports cars to show how much money they had and how they were playing around with it. The producers told him that they didn’t have the budget for that only a couple of weeks before it was to be shot. They went through other expensive things they could blow up, and found all these things would be expensive to fake — until they hit on the idea of a pile of money, and realised that money itself isn’t expensive. Ezban said he was in fact surprised how expensive a big pile of fake money is. But he realised he could easily set up the scene by inserting a line earlier for one of the characters. The actors had the idea that their characters would dress up like the A-Team, but Ezban wasn’t sure the A-Team would be understood everywhere, and they decided the characters would dress like mobsters from The Godfather instead. This all helped set up the characters’ relationship in the second half of the film.

Blaszek was asked how he wrote the script, keeping everything straight, and he said there was a lot of editing. The script changed a lot from the first to the last draft. Some character arcs worked well, but some changed significantly. There had to be a lot of outlining and rewriting, and a lot of colour-coding with scenes set in alts and not. At one point he drew an image on a whiteboard to explain it to himself, and that took a lot of work, but the image ended up appearing in the film as the characters figured out how things worked. Zaorzirny said they made what he called a “mythology document” with all the rules of the machine, how time-dilation worked, and so forth. He said while the idea might sound fancy, it’s useful for science-fiction and horror, keeping straight how vampires could be killed and the like. It’s easier to establish those rules early in the process rather than in the third draft.

Blaszek was asked how he wrote the script, keeping everything straight, and he said there was a lot of editing. The script changed a lot from the first to the last draft. Some character arcs worked well, but some changed significantly. There had to be a lot of outlining and rewriting, and a lot of colour-coding with scenes set in alts and not. At one point he drew an image on a whiteboard to explain it to himself, and that took a lot of work, but the image ended up appearing in the film as the characters figured out how things worked. Zaorzirny said they made what he called a “mythology document” with all the rules of the machine, how time-dilation worked, and so forth. He said while the idea might sound fancy, it’s useful for science-fiction and horror, keeping straight how vampires could be killed and the like. It’s easier to establish those rules early in the process rather than in the third draft.

In answer to an audience question, Ezban observed that Hussein likes practical effects and that this was a film about mirrors — so characters from alts would be shot in mirrors in this world, for example. The myth document was useful for this as well. Because so much was done practically, the film needed almost no post-production work. In answer to a question about the film’s ending, Ezban said that they wanted to keep some things open, and at one point had a cut that answered the question and deliberately chose a more ambiguous version.

That ended the long day of movies for me, part of the busiest stretch for me at this year’s Fantasia. I’d have only a short time for sleep, and then the next day would bring another four films — including an unusual triple-bill.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.