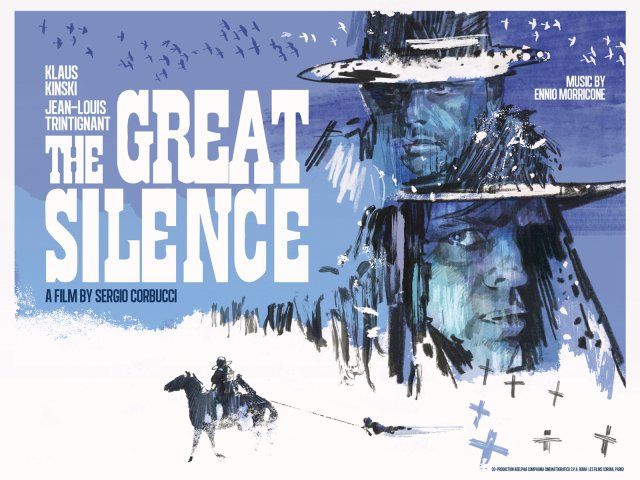

The King Lear of the Euro Western: The Icy Death of The Great Silence (1968) Arrives in North America

I don’t normally put up spoiler warnings for a movie of this vintage, but The Great Silence hasn’t been widely available in North America until recently, so few viewers outside of Europe and Japan have had the chance to experience it. Since it’s almost impossible to discuss the movie in any depth without talking about its ending, this is your spoiler warning from here onward. If you’d rather experience the film first, it’s now available on streaming platforms (Amazon, iTunes, Vudu) and a stunning new Blu-ray from a 2K remaster.

The term “Spaghetti Western” or “Italian Western” conjures images roasted under a relentless sun. A cyclorama of the barren lands of Southwestern U.S. and Northern Mexico, as played by Spanish locations. A thinly populated dryland of cracked mud and twisted cacti, dying towns clustered about decaying Catholic churches, and vultures on hanging trees. Heat suffuses and twists everything. Sweat and grime stain every character’s face.

Sergio Corbucci’s Western masterpiece, The Great Silence (Il grande silenzio) takes place in the relentless wastes — but one that swaps the usual Italian Western deadlands for one of ice and snow. Corbucci plunges viewers into a world of iron mountains, frozen lakes, and gnawing wind. In theory, much remains the same: an inhospitable and lawless place. In practice, the climate switch makes The Great Silence unique among the Euro Westerns of the ‘60s.

The “snow Western” is a peculiar but fascinating subgenre, and The Great Silence is the bleakest example of what winter can bring to Western storytelling. Among the other examples of snow Westerns — William Wellman’s 1954 Track of the Cat, Andre DeToth’s 1959 Day of the Outlaw (an influence on Corbucci), Robert Altman’s 1971 McCabe and Mrs. Miller, the 1999 cannibal black comedy Ravenous, and Quentin Tarantino’s recent The Hateful Eight (hugely indebted to Corbucci) — The Great Silence has become the go-to for the subgenre, even with its limited availability. It was banned from the UK outright in 1968 and didn’t receive a U.S. theatrical release. It only reached home video in North America in a 2002 DVD from Fantoms that only feats red the English dub and wasn’t anamorphic. The Fantoma disc soon fell out of production. Now on Blu-ray from Film Movement in a gorgeous restored print and available on several VOD services, The Great Silence may finally receive the wider appreciation it deserves as one of the best Italian Westerns outside of the Sergio Leone canon.

Fair warning: the film is going to depress and possibly anger plenty of new viewers. The King Lear comparison I made in this title isn’t one of raw quality — The Great Silence is an excellent film, but not that excellent — but of emotional impact and apocalyptic conclusion. King Lear has devastated audiences and readers for centuries with its ending that barely leaves scraps of hope. (“Is this the promised end?” “Or image of that horror?”) The Great Silence takes the conventions of the already dark avenger Western and rips away any shreds of consolation from viewers, and then drives a few knives into their wounds for good measure. Placing the story in the “great silence” of the dead of winter makes the knife cuts sting sharper.

Director and co-writer Sergio Corbucci had already made a massive impact on the Euro Western with Django (1966), the film that launched dozens of imitations. Corbucci originally wanted to film Django in the snow, but it was prohibitively expensive, so he settled for mud instead. The Great Silence is Django re-done to Corbucci’s original planned icy setting, with additional political subtext, a more enigmatic hero, and almost the same finale — but with a crucial difference, which I’ll get to.

Eh, on second thought, let’s just do it now and put that spoiler warning to work.

At the conclusion of Django, the eponymous gunslinger has his hands viciously broken with rifle butts so he can’t fire his pistol. He crawls to a cemetery to wait for the villains, and as they close in to finish him off, he props his gun up on a metal cross and fans it to kill all his opponents.

In The Great Silence, the hero finds himself in a similar fatal dilemma: his hands are horribly burnt so he can’t use his gun. He trudges out to confront the villain and his bounty hunter companions, attempts to pull his gun — and gets shot in the hands, the gut, and finally the head. Dead, face down in the snow. The heroine runs to his side. The villains shoot and kill her too. The bounty hunters then unload their pistols and rifles on the innocent farmers they’ve taken as hostages and slaughter them all. The bounty hunters mount their horses and ride off, almost unscathed. All the sympathetic characters are dead, not even a noble sacrifice among them, and the greedy, psychopathic murderers ride away with no punishment.

You don’t often see endings as unhappy as this. It’s a horror movie ending — and an extreme horror movie at that. But it makes the movie. All the other rough spots of The Great Silence, the loose plotting, jagged editing and blocking, awkward moments of comedy relief, they fade in the pitch-black shadow of the nihilistic curtain closer. You may see a hundred Italian Westerns and forget the specifics of three-quarters of them, but the ending of The Great Silence ensures you’ll remember it.

The movie that builds to this climax is often as rough as its wilderness setting. Corbucci as director and writer was often slack with mechanics and details, directing with a hyperactivity that could overwhelm sense. He’s more constrained in The Great Silence than in his more action-filled Westerns like Django, Navajo Joe (1966), and Compañeros (1970), but he still directs with a looseness that makes the film difficult to grasp onto for long stretches even as it manages to coast along on its mood.

The script links together the prototypical lone gunfighter on a vague quest with other plots: a band of farmers forced into the hills by the rapacious capitalist/lawman of the town of Snow Hill; the widow Pauline (Vonetta McGee) seeking revenge for her murdered husband; a humorous sheriff (Frank Wolff) sent to bring law to Snow Hill before the governor offers amnesty to the farmers hiding the hills; and a pack of ruthless bounty hunters wandering the cold wastes seemingly without plan, hoping to stumble on one of the outlawed farmers so they collect a few bucks for his hide.

These strands don’t begin to weave together until the second half as events and characters converge on Snow Hill. Most of the action surrounding the bumbling Sheriff Corbett (“Burnett” in the English dub) feels out of step with the rest of the movie. Corbett is the hapless figure of the law who can’t do anything against the avarice of town tyrant Henry Pollicut (Luigi Pistilli) — Corbucci’s symbol of heartless capitalism — or Pollicut’s deadly tools, the bounty hunters. From the moment he’s introduced, Corbett’s destiny is to be dispatched, and the film is only able to move into the finale once its comic relief is dropped into a freezing river.

The solo gunfighter figure is Silence, played by French actor Jean-Louis Trintignant. Silence is modeled on other terse Euro Western heroes, but his terseness is literal: he cannot speak because his vocal cords were cut when he was a child. Although audiences are given more human moments with Silence than with other lone gunfighter characters, such as an odd and beautiful love scene between him and the widow Pauline and a flashback to his family’s murder, he’s still put at a distance from viewers and at times borders almost into mercenary territory. He loathes bounty hunters, but he’s not a superhero who rides to the rescue unless he’s paid or the situation becomes extreme. Trintignant’s performance is appropriately icy and inscrutable.

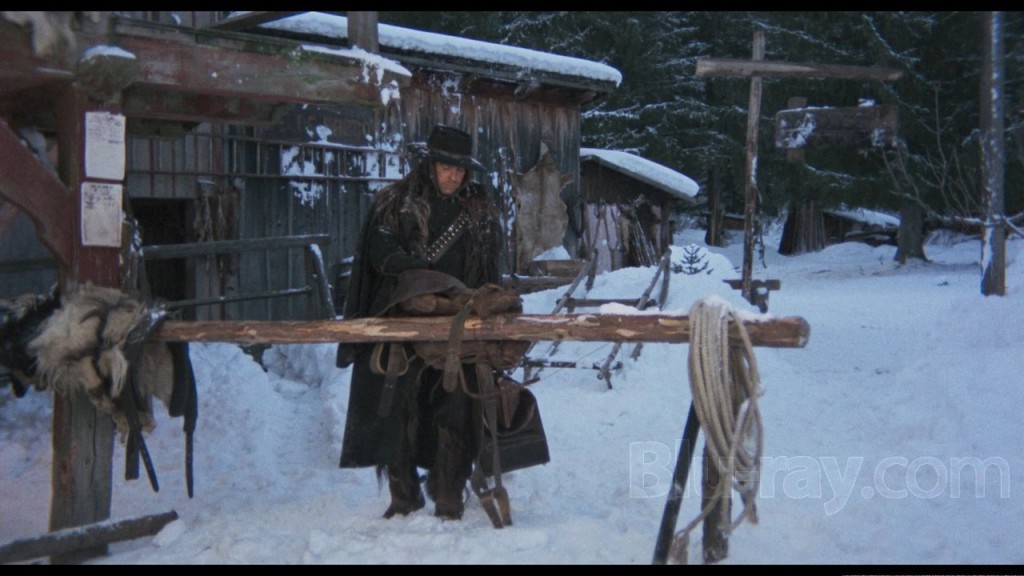

His opposite in the cast is the wild and uncontrolled show put on by Klaus Kinski as the lead bounty hunter, Tigrero (changed to “Loco” for the English dub for reasons of subtlety, I guess). Tigrero is a psychopath with cold eyes similar to Silence’s, but offset with a lunatic grin and a loony fashion sense that mixes a preacher’s hat with an old woman’s shawl. Playing a psychopath wasn’t difficult for Kinski, and his ability to act with such joy in his character’s cruelty makes for a genuinely repulsive, hateful character. Tigrero is superficially motivated by money, but his real drive is inflicting suffering. He could have exited the story early with his reward, and he doesn’t have any good reason to go after Silence, but his psychopathy ensures he stays around until every decent person is dead.

Two alternate endings exist, both included on the new Blu-ray. They were apparently created for North African countries where the bleakness of the original ending was thought too extreme. There’s no evidence these versions ever screened. The first alternate ending is a re-cut that makes Silence’s death less brutal (the slow-mo shot to his head is gone) and cuts out the killing of Pauline and the hostages, making it look as if Tigrero and the other bounty hunters simply left after gunning down Silence. It feels exactly like what it is: something clumsily edited down. The other ending, which until this Blu-ray release was missing audio, is a completely new scene where Sheriff Corbett suddenly rides to the rescue, with no explanation how he survived Tigrero dropping him into a frozen lake. Silence is able to gun down all the bad guys thanks to a bizarre metal gauntlet on his hand (when did he make that?) and saves the day. It’s … really bad. The same way Nahum Tate’s 1681 adaptation of King Lear, which gave the play a happy ending, shows how organic Shakespeare’s apocalyptic conclusion is, The Great Silence makes no sense with an upbeat finale tacked onto it. These alternate endings have the effect of justifying the intended ending.

The exteriors were shot primarily in Cortina D’Ampezzo in the Dolomite Mountains, a famous and posh ski resort. But you would never know that from the photography of Silvano Ippoliti, which makes the mountains and forest the most inhospitable location imaginable. Fog and dark imagery help disguise the scenes that were shot with shaving cream standing in for snow. Ippoliti creates some remarkable images using the frozen canvas, such as Tigrero on his horse appearing to emerge out of solid white. The camera work still suffers from some of Corbucci’s hyperactivity (handheld zooms that don’t quite end up on their target at first), but the consistency of the snowbound look is impressive. It can make you want to bundle up on a hot July day.

Ennio Morricone’s score is one of his finest, and he considered it his best achievement in the Western after his work for Leone. The often boisterous, rousing sound of other Morricone Western scores is replaced with music that’s at various points solemn, eerie, and agitated. Action passages such as Tigrero whipping one of his bounties and dragging him through the snow are accompanied by angry noises of percussion, bells, and electric guitars. Strange sound textures of sitar and wordless choruses are the backdrop for the cold emptiness. And the main title (“Restless”) is one of Morricone’s most haunting melodies, making striking use of the last instrument you might expect in a Western: the harpsichord.

The Blu-ray and streaming versions come with the option to watch the film with its English dub or in Italian with subtitles. Kinski and McGee are dubbed in both versions and Trintignant never speaks, which should make the English dub as attractive a choice as the Italian. However, the English dubbing script makes a number of changes that weaken the film, and Kinski’s performance is lessened by the English actor’s performance, so I recommend sticking with the Italian version with the English subtitles, which also has superior sound quality.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. His most recent publication, “The Invasion Will Be Alphabetized,” is now on sale in Stupendous Stories #19. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a marketing writer. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Not going to read the article yet, but I just put the movie at the head of my Netflix queue.

“He trudges out to confront the villain and his bounty hunter companions”

Unfortunately, this is what really kills the movie for me. Instead of being blown away by how bleak the ending is, all I take away from it is, “Man, that guy was a complete moron.” He literally takes no precautions, just walks out there alone vs. a whole bunch of guys and…loses. If they worked the climax in such a way that he’s outdone despite making an attempt at evening the odds, the end would work for me as intended, but as it is, it feels kind of like a pro wrestling storyline that got derailed because the lead babyface got busted for drug possession after the previous show and they had no choice but to put the villain over strong and start building up someone else.

OK, and having now watched it (thank you, Netflix!), I’m really glad I didn’t read the full review until after watching the movie. I have to admit I kept waiting for Our Hero to somehow win the day until, well … Oh. I guess it’s going to be _that_ kind of ending.