Fantasia 2017, Day 21: The Last Breath (Indiana, Fashionista, and Suspiria)

On the last day of the 2017 Fantasia film festival I planned to watch three movies. First, at the De Sève Theatre, Indiana: a movie about a pair of ghost-breakers in the Midwest who may or may not deal with actual paranormal events. Second, I’d go to the festival’s screening room, where I’d see a dark psychological thriller called Fashionista. Finally, I’d close out the festival with a screening of a restored version of Dario Argento’s classic 1977 horror film Suspiria.

On the last day of the 2017 Fantasia film festival I planned to watch three movies. First, at the De Sève Theatre, Indiana: a movie about a pair of ghost-breakers in the Midwest who may or may not deal with actual paranormal events. Second, I’d go to the festival’s screening room, where I’d see a dark psychological thriller called Fashionista. Finally, I’d close out the festival with a screening of a restored version of Dario Argento’s classic 1977 horror film Suspiria.

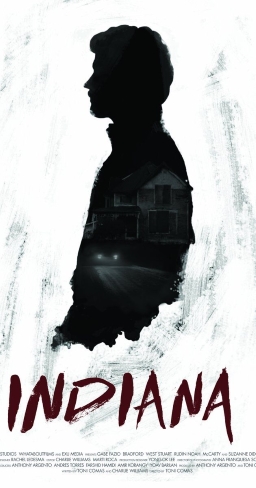

Indiana began the day for me, a film directed by Toni Comas from a script by Comas and Charlie Williams. It follows Michael (Gabe Fazio) and Josh (Bradford West), two ghost hunters in early middle-age who travel the roads of the Midwest hunting for spirits and people suffering hauntings. They’ve carved out a level of fame for themselves as the Spirit Doctors, doing radio call-in shows and occasionally arguing with skeptics — which latter role the more extroverted Josh takes to more naturally than the quieter Michael. Michael’s got another higher-paying job and is thinking about quitting his ghostbusting days, while Josh is dedicated to the profession, and even takes his son Peter (Noah McCarty-Slaughter) on the road with them. Meanwhile, a parallel narrative track follows Sam, an old man on a seemingly-nefarious mission. What drives him, and how his story links up with the Ghost Doctors, becomes part of the mystery of the film.

It’s a fascinating narrative construction, and it works surprisingly well. One might say Indiana as a whole works surprisingly well: it’s difficult sometimes to get a sense of how one is to watch the story, not so much whether to treat it as horror or drama or comedy as how the presence of all these things are to be understood in playing off against each other. The movie’s remarkably understated, with much more implied than stated. But it works, in the end. Sam’s thread is a key part in the delicate tonal patterning of the film; we see him commit an act of violence, and that hangs over the movie as we sense that sooner or later he’s going to cross paths with the Spirit Doctors — who we’re getting to know and like, whose flaws we empathise with. And yet when all the characters come together it’s nothing really like what we’ve been expected.

It’s a fascinating narrative construction, and it works surprisingly well. One might say Indiana as a whole works surprisingly well: it’s difficult sometimes to get a sense of how one is to watch the story, not so much whether to treat it as horror or drama or comedy as how the presence of all these things are to be understood in playing off against each other. The movie’s remarkably understated, with much more implied than stated. But it works, in the end. Sam’s thread is a key part in the delicate tonal patterning of the film; we see him commit an act of violence, and that hangs over the movie as we sense that sooner or later he’s going to cross paths with the Spirit Doctors — who we’re getting to know and like, whose flaws we empathise with. And yet when all the characters come together it’s nothing really like what we’ve been expected.

One must note here the cinematography, from Anna Franquesa Solano. It’s stylish but not obtrusive, capturing the ordinariness of rural life and then also what in it is extraordinary: the darkness of night, the patina of age in a decaying house. Shadow and silhouette is used here to great effect, bringing out a sense of dread and horror when needed, while allowing the film to breathe in the scenes of everyday drama. In other words, the images bring out the sense of profound spiritual realities surrounding the mundane world while also finding an interest in the mundane itself.

Again, the film succeeds because of that kind of balancing act; because of the way it shows everyday life as slightly askew in a way we recognise, and also as interacting with deeper conditions of life. Whether or not spirits exist in this movie — and it is perhaps possible to make the argument either way — deep abysses of emotion and soul certainly do. The film strikes me as being in large part about that kind of tension.

There are other ways of looking at it, though. For example, I think I could make an argument that this film, more than any other I saw at the festival, speaks to the current state of middle America — far more so than something like Tilt, which uses the last political campaign as part of its text. Here, we get a portrait of a land in trouble; a Midwest filled with low-wage workers at roadside fast-food stands and gas stations, with divorced men struggling to raise kids, with homes aging and people everywhere who feel haunted by things they cannot name. There’s a depiction here of a general malaise, something people can’t look at directly, can’t really articulate, a history that manifests as the supernatural.

At which point the Spirit Doctors enter the picture, travelling the back roads to bring some hope to people who don’t know where else to look. What is interesting is that they’re not con men. They take their job seriously, especially Josh; Michael’s less sure, and so one could also interpret the movie as his quest for a better sense of spiritual reality. In any event they’re recognised by the people they meet, not mocked but looked to as useful professionals. There’s a darkness in the lands they travel, and they’re the men who can provide a way to conceptualise it, to deal with it.

The film itself allows that unstated sense of horror to come through indirectly, as atmosphere. There’s a wonderful sequence at a possibly–haunted house involving Peter and a little girl which stands as a strong example: two children meet each other, one invites the other to play with her toys, and as you watch you think there’s nothing unwholesome here and yet. And yet there’s a sinister atmosphere cast over everything by the weight of that unarticulated past.

The film itself allows that unstated sense of horror to come through indirectly, as atmosphere. There’s a wonderful sequence at a possibly–haunted house involving Peter and a little girl which stands as a strong example: two children meet each other, one invites the other to play with her toys, and as you watch you think there’s nothing unwholesome here and yet. And yet there’s a sinister atmosphere cast over everything by the weight of that unarticulated past.

Indiana’s a lovely illustration that understated doesn’t mean undramatic. It’s the perfect length, at 76 minutes. Any longer and the slenderness of the drama would stand out. Any shorter and the material that is here would be shortchanged. The characters are sketched in with exactly as much depth as we need; conflicts and issues emerge, real things that don’t need to be hammered on. The sense of the supernatural and of extreme states textures the film and shapes its theme, making it an eccentric kind of horror film that isn’t, most of the time, scary — but a film that catches us at odd moments, that makes as much use of sunlight as shadows, that slowly develops through an unusual structure to a powerful climax. It’s tremendously effective.

From Indiana I went to Fantasia’s screening room, where a selection of films playing the festival were available for critics to watch on a computer monitor. It’s not the best way to watch a film, but a useful means of seeing something when one can’t make it to a theatrical screening. I hadn’t resorted to the screening room so far in 2017, but with a couple of hours to the showing of Suspiria that would end the festival for me, I decided to look over what was on offer. I decided to watch a suspense thriller called Fashionista.

Written and directed by Simon Rumley, Fashionista follows a woman in Austin, Texas, named April (Amanda Fuller). She’s in a relationship with Eric (Ethan Embry), owner of Eric’s Emporium, a thrift store with an extensive selection of second-hand clothing. April’s life seems ideal, but then she begins to suspect Eric’s cheating. As she becomes more and more obsessed with the idea of infidelity, her life goes further and further off the rails. Clothing, and especially the massive collection of clothes the couple’s stored up, becomes a symbol of her life and identity; and the drama becomes even more extreme when April meets the sinister Randall (Eric Balfour), with whom she begins an affair of her own.

Written and directed by Simon Rumley, Fashionista follows a woman in Austin, Texas, named April (Amanda Fuller). She’s in a relationship with Eric (Ethan Embry), owner of Eric’s Emporium, a thrift store with an extensive selection of second-hand clothing. April’s life seems ideal, but then she begins to suspect Eric’s cheating. As she becomes more and more obsessed with the idea of infidelity, her life goes further and further off the rails. Clothing, and especially the massive collection of clothes the couple’s stored up, becomes a symbol of her life and identity; and the drama becomes even more extreme when April meets the sinister Randall (Eric Balfour), with whom she begins an affair of her own.

The first thing I have to say is that seeing this in the screening room was an unfortunate way to view the movie. It’s clearly got a strong sense of visual design and a rich colour sense (confirmed, incidentally, by the stills and trailer I’ve seen). The version I saw was relatively low-resolution, so while I had no problem following the action and picking out details, some of the aesthetic was lost. Still, although the film did play tricks with chronology and continuity, I think I grasped enough to write about it.

Broadly, this is a film about identity and mental stability. In part it’s about obsessions, sexual and otherwise, and the line between obsessions and addictions; and then how those things play into one’s identity. It is, I think, about how we construct ourselves, and how we construct images of ourselves. Also how we build our understanding of the world, and how those understandings can be shaken. So April’s journey through the film leads her to confront all of those things, and by the end she is changed in ways we can hardly grasp.

Changes, in fact, deeply enough to lay Rumley open to charges of game-playing. This is a movie that makes no bones about using storytelling techniques that tend to undermine straightforward ideas of narrative and character. Flash-forwards, as one example. More generally, without wanting to give too much away, the line between reality and hallucination is blurred early and often, not always with any obvious sign. How one feels about this, I think, depends on how much one feels they understand about April’s character at the end. At one viewing, I felt that I understood generally what had happened, and who April in essence was. Others might not be so comfortable with that kind of assessment. Even to me, I felt that the film was easier to respect than to enjoy.

So, for example, as a suspense film, things build reasonably well, but by the end one is left doubting much of what one has seen. The suspense is undermined, the genre elements revealed as a kind of chrome; a structure on which to hang some character traits, in a way. Which is appropriate given the use of clothes as symbol, but as story feels empty. Coincidences that accrue throughout the film have no particular explanation other perhaps than dream-logic, and if that makes sense, it’s still difficult to swallow. On the other hand, precisely because of those coincidences, the genre elements feel slapdash and poorly thought-through; leaving them behind is in that sense almost a relief, like (the simile insists on itself) taking off too-tight shoes.

So, for example, as a suspense film, things build reasonably well, but by the end one is left doubting much of what one has seen. The suspense is undermined, the genre elements revealed as a kind of chrome; a structure on which to hang some character traits, in a way. Which is appropriate given the use of clothes as symbol, but as story feels empty. Coincidences that accrue throughout the film have no particular explanation other perhaps than dream-logic, and if that makes sense, it’s still difficult to swallow. On the other hand, precisely because of those coincidences, the genre elements feel slapdash and poorly thought-through; leaving them behind is in that sense almost a relief, like (the simile insists on itself) taking off too-tight shoes.

At any rate, the movie does do an interesting job in juggling its themes. If its point of interest is not in the creation of a well-made plot, it has much more of a fascination with exploring imagery and using its symbols to bring out theme. So April and Eric are gentrifiers, living in a gentrified city; and their job is refitting used goods for resale. The past sustains them — even in their bedroom we see old posters and second-hand things. The argument of the movie in a way is that this isn’t enough, that all the stuff of their lives is only for the sake of creating roles that confine them, that are ultimately unreal. Whatever authenticity is, this hipster gentrification isn’t it.

Clothes, for April, become the ultimate symbol of her attempt to construct herself and also of how she allows herself to be constructed. She’s drawn to them sensually, she makes them a part of herself, but also in certain contexts is made to wear specific things, to be a specific person for a specific reason (mostly at the implicit or explicit command of Randall). Her clothes define her femininity and sexuality, define how she sees herself, but also define how the men around her define her. There’s a level on which this is obvious, and using a visual metaphor for a character’s personality isn’t surprising in a visual medium. What is more surprising is how far Rumley’s able to push this kind of image, and how he’s able to come up with an unexpected yet coherent way to demonstrate how thoroughly April’s changed by the end of the film; how much she has abandoned her obsession.

Clothes, for April, become the ultimate symbol of her attempt to construct herself and also of how she allows herself to be constructed. She’s drawn to them sensually, she makes them a part of herself, but also in certain contexts is made to wear specific things, to be a specific person for a specific reason (mostly at the implicit or explicit command of Randall). Her clothes define her femininity and sexuality, define how she sees herself, but also define how the men around her define her. There’s a level on which this is obvious, and using a visual metaphor for a character’s personality isn’t surprising in a visual medium. What is more surprising is how far Rumley’s able to push this kind of image, and how he’s able to come up with an unexpected yet coherent way to demonstrate how thoroughly April’s changed by the end of the film; how much she has abandoned her obsession.

It is by contrast not that surprising to find that the movie’s dedicated to Nicholas Roeg, another visual stylist who isn’t afraid of using disconcerting techniques to undermine narrative (Roeg has executive produced Rumley’s recent film Crowhurst). It’s clear that the film’s a deliberate visual statement, in its use of colour, in its long takes and careful framing. It’s tempting to think that this comes at the expense of narrative coherency, but it may be more accurate to say that it casts the narrative in a specific light — as something with the heightened feel of a dream. In this way the film helps prepare us for the revelations at the end. Whether the final twists undermine the story too much while establishing character is, to me, an open question; virtually everything we’ve seen is undermined. But then, one might ask if that’s such a problem. In a way vaguely like Lynch’s Mulholland Drive we do get enough to know that we’ve been given the basic situation of the film. If everything else we’ve seen is only a fiction, well, didn’t we know we’d be watching a fiction going in?

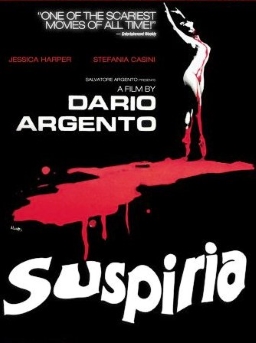

I was still considering this when I made my way to the Hall Theatre for Suspiria. It was a wonderful way to close out the festival, not least because it seemed as though everyone else I knew at Fantasia was going to see it as well. What we saw was a restoration that had taken four years, and involved the movie’s original cinematographer. The result is a version of the film in 4K, with the original 4.0 surround sound adapted to modern theatrical and home sound systems, and a lush sense of colour. (This new version’s just been released on blu-ray, if you want to see it for yourself.) The film’s widely considered a masterpiece, and seeing this restored version it’s almost instantly clear why.

I was still considering this when I made my way to the Hall Theatre for Suspiria. It was a wonderful way to close out the festival, not least because it seemed as though everyone else I knew at Fantasia was going to see it as well. What we saw was a restoration that had taken four years, and involved the movie’s original cinematographer. The result is a version of the film in 4K, with the original 4.0 surround sound adapted to modern theatrical and home sound systems, and a lush sense of colour. (This new version’s just been released on blu-ray, if you want to see it for yourself.) The film’s widely considered a masterpiece, and seeing this restored version it’s almost instantly clear why.

Directed by Dario Argento, and written by Argento with Daria Nicolodi, it’s the story of Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), a ballet student from America who travels to Italy to study at the Tanz Dance Academy in Germany. She arrives on a dark and stormy night, and as she reaches the academy another girl (Eva Axén) flees; who is she, and why is she so scared? Suzy doesn’t know, but we follow the other girl and see her brutally murdered. There’s something sinister going on at the academy. Suzy falls ill, and is made to stay at the school. Mysteries deepen. Maggots fall from the ceiling. People die. And Suzy begins to suspect there’s witchcraft afoot at the strange academy.

All of which barely scratches the surface of what goes on in this film. It’s a riot of invention, visual and otherwise. The best I can describe it is to say that it’s the sort of film one hopes to watch on Halloween: a scary movie that captures not just the horror but the feverish invention and unpredictability of that night. It’s like a fairy tale in horror-movie clothing, a rich and strange fable of witchery, strange power, and innocence.

Visually, it’s easily one of the best-looking movies I’ve ever seen. The Tanz Academy is an art-nouveau dream, every room a different colour, like something out of Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death” or Huysmans’ À rebours. Designs on the walls might have come from Mucha or Aubrey Beardsley. The restoration here shows itself to e necessary and important: the colours are vibrant and precisely balanced, giving every moment its own exquisite atmosphere, and a feverish beauty to the whole.

Aurally, the soundtrack by Italian prog-rock group Goblin is justly famous. Hearing it echoing all around the theater, it perfectly accompanies the visions on the screen. It’s overpowering, but in just the right way. It pulls one in to a heightened reality in just the way that movie music’s supposed to, but which it rarely does — at least to this extent.

Aurally, the soundtrack by Italian prog-rock group Goblin is justly famous. Hearing it echoing all around the theater, it perfectly accompanies the visions on the screen. It’s overpowering, but in just the right way. It pulls one in to a heightened reality in just the way that movie music’s supposed to, but which it rarely does — at least to this extent.

Suspiria’s a gripping film less because of the precision of its plot than its incredible oneiric sense of latent power. There’s a lot of subtext one can read into the film. Not necessarily sexual subtext either; in fact, it’s likely the least sexualised horror film about a girls’ school ever made (Argento had been planning to have the girls be around age 12 when he wrote the film, only for his father and producer Salvatore Argento to point out that a film with such young children and such graphic violence would be banned; Argento cast 20-ish actresses without rewriting the dialogue, and instead leaned in to the childlike nature of the characters). Suzy does grow and change through the film, but does so essentially by passing inward to a secret realm. I note that a key secret door is opened by the manipulation of a blue flower, as though recalling the blue rose of German Romanticism, symbol of art and imagination. And the dance academy, an art school, is everywhere filled with art and colour, as though the embodiment of 1890s decadence.

It’s weirdly like a Henry James novel: a young innocent American comes to Europe, where she falls afoul of older sophisticated Europeans. The art of the film, the sheer stylisation of it, works with this reading: everything’s artificial and heightened because this is the world in which Suzy finds herself, the artificial hothouse she must destroy in order to find freedom. The movie ends abruptly, but with a supreme act of catharsis following an almost surreal plunge into nightmare; it builds steadily, almost without you noticing it, as Suzy is pulled literally and figuratively deeper into the maze until she finds the evil at its heart. The school is both her home and the greatest threat to her, a gothic edifice that rears her and teaches her but which she must ultimately destroy more thoroughly than the poor girl she passed at the start of the film — a girl whose fate must foreshadow Suzy’s, unless Suzy can overcome the malign forces pulling her in to the school.

I suspect the film works in part because of the lack of overt sexuality; because things are kept on a subliminal level. The threatening forces here are older women; the images of power and danger are both women. Men are marginal; there is a scene where Suzy and her friends talk about a boy, but there’s an odd innocence to it (appropriate for 12-year-olds). Similarly, although there is graphic violence in the film, there’s less of it than one might expect. Again, it’s latent; the movie broods, and there’s a sense that absolutely anyone might die at any time, something far more terrifying and unpredictable than any series of killings, however grisly, might be.

I suspect the film works in part because of the lack of overt sexuality; because things are kept on a subliminal level. The threatening forces here are older women; the images of power and danger are both women. Men are marginal; there is a scene where Suzy and her friends talk about a boy, but there’s an odd innocence to it (appropriate for 12-year-olds). Similarly, although there is graphic violence in the film, there’s less of it than one might expect. Again, it’s latent; the movie broods, and there’s a sense that absolutely anyone might die at any time, something far more terrifying and unpredictable than any series of killings, however grisly, might be.

Argento based the movie on De Quincey’s Suspiria de Profundis, and more precisely his essay “Levana and Our Ladies of Sorrow.” It’s an essay about dreams, birth, the education of children, and about powerful female figures, the three Sorrows who De Quincey imagined as companions to Levana, Roman goddess of childbirth: “Like God, whose servants they are, they utter their pleasure, not by sounds that perish, or by words that go astray, but by signs in heaven, by changes on earth, by pulses in secret rivers, heraldries painted on darkness, and hieroglyphics written on the tablets of the brain. They wheeled in mazes; I spelled the steps. They telegraphed from afar; I read the signals. They conspired together; and on the mirrors of darkness my eye traced the plots. Theirs were the symbols; mine are the words.” So from his vision of these figures, Argento like De Quincey drew inspiration for art. De Quincey’s prose poetry is a suitably baroque inspiration for the visions Argento put up on the screen. It’s a stunning, mind-altering movie; like On the Silvery Globe last year, a tremendous thing to see on the big screen, and the best way I might have imagined to conclude the Fantasia Festival for another year.

Or very nearly. As I left the Hall for the last time in 2017, I had links to three other movies to watch at home. I’ll have one more post, then, about those films; and then some thoughts about the festival as a whole, and what I have come to believe about the state of genre filmmaking.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.